| The Medieval Town

Little is known about the town, other than what is

recorded in the Domesday Book, until 1164 when King

Henry II exchanged it for the manor of Stonesfield. At

the time, the King had a large manor at Woodstock in

Oxfordshire, with extensive land on which he built a

pleasure ground for his mistress Rosamond de Clifford.

He needed the land at Stonesfield, which belonged to the

barony of d’Oyley for part of the manor grounds. After

the exchange Wednesbury came under the control of

d’Oyley’s tenant Ralph Boterel, who became lord of the

manor.

Payments made to the Crown were

recorded in the Exchequer Records, known as the Pipe

Rolls. Wednesbury had a taxable value of £4 a year,

whereas Stonesfield was only worth £3 a year. To balance

matters an agreement was reached in which Boterel would

still owe service as a Knight to the barony and also pay

an annual rent of one pound to the crown. Boterel died

in 1181 and the records show that he had never paid his

rent. When William de Heronville took over the manor in

1182 he was charged with 18 years arrears, which he

immediately agreed to pay. William became lord of the

manor after marrying Boterel’s daughter and heiress.

William rented the mill to the

monks of Bordesley Abbey for 10 shillings a year. By

1225 William had passed away, and in January 1226 his

son, also named William became lord of the manor.

William conveyed the mill to the monks of Bordesley

Abbey, who in turn sublet it to the Hillary family,

lords of the manor of Bescot, for a free farm rent,

which was usually set at one third of the taxable value

of the property. This meant that the Hillary’s paid rent

and took the profits from the compulsory payments that

were made by the local population for their use of the

mill.

John

de Heronville

In about 1255 William was succeeded

by Simon de Heronville, who died in 1259. His son and

heir, John succeeded him, but had not yet come of age.

As a result he became the ward of the Earl and Countess

of Warwick, who had taken over the barony of d’Oyley by

marriage. He came of age around 1261, and his son and

heir, Henry was born in 1265. John married twice. His

first wife was the sister and one of the heirs of

William Fitzwarren of Tipton and as a result he gained a

share in the manor of Tipton. He later married Juliana,

who outlived him.

John took up his knighthood in 1272

because it was the king’s policy that all lords of the

manor should do so. The two lions on his shield

eventually formed the basis of the borough’s coat of

arms. He became one of most prominent knights in the

county and along with three others chose the members of

the county jury, becoming a juror himself on more than

one occasion.

John became one of the four

Verderers of Cannock Forest. They were the officials who

were elected by the freeholders to administer the laws

regarding the forest. The Verderers’ Court would meet to

settle disputes etc. In those days the forest extended

from Cannock into Wednesbury, and covered about a half

of the manor. John also paid fines for some of his

tenants when they illegally felled trees or converted

woodland into farmland.

F.W. Hackwood in his “Wednesbury

Ancient and Modern” suggests that the forest ended along

the line of the present High Street, to Oakeswell End,

then along Hydes Road to the Tame, following the river

along the Bescot boundary.

Many towns such as Wednesbury held

manorial courts called Court Leets. They date back to

Saxon times and survived the Norman conquest without any

great change taking place. John had the right to hold

such a court in which the officers were the Steward, the

Reeve (who acted as an intermediary between tenants and

lord of the manor), the Constable, the Haywards (who

supervised and maintained the boundaries) and the Jury

men. The Steward had a very important role; he

supervised the estate, organised its economy and

maintained justice. A full account of all that happened

during each year in the manor had to be submitted to the

lord of the manor in an annual statement called the

Account Roll.

The principal functions of the

court were the preservation of the rights of the lord of

the manor and the regulation of relations between

tenants. It dealt with breaches of the peace, criminal

affairs and ensured that the tenants carried out their

statutory obligations. The court also upheld the “assize

of bread and ale” by appointing ale tasters to ensure

that standards were maintained.

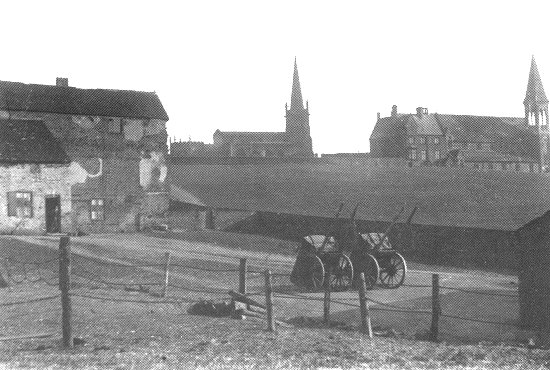

What remained of the manor house

in 1892. From an old postcard.

John was clearly forthright in his

views and would vigorously defend his rights against

anyone who challenged them. In 1272 he was sued by 20 of

his tenants in the Court of King’s Bench. Although

disputes would usually be settled in the Court Leet, the

tenants of Wednesbury collectively brought an action

against their lord in the hope that the royal court

would change the rules within the manor. They felt that

they were unfairly treated by John who demanded extra

customs and services from them than were rendered when

the manor was in the hands of the King. The case would

continue for many years with several suits being taken

against him. John simply ignored the rulings made by the

court, who ordered him to return the goods and chattels

that he had seized from the tenants. In 1280 he was in

contempt of the court and prosecuted by the crown. The

quarrel went on for thirty years, during which time

relations between the lord and tenants must have become

strained to say the least. Unfortunately the court’s

final decision on the matter is not known.

John was also involved in a number

of other disputes. In 1280 he was accused, along with

two of his tenants, of dispossessing Henry de Bruly of

property in Wednesbury. The case was thrown out because

Henry’s writ had no validity at the assizes, and should

have been considered at the manorial court. In another

case at the assizes in 1293, William de Darlaston

claimed that he had been dispossessed of his right of

common in Wednesbury. This time the court tried the

claim, but it was rejected because Wednesbury was an

ancient manor, and Darlaston, where the building to

which the alleged right of common existed, was not.

|

|

The area occupied by the old town. |

In 1286 Thomas Hillary took John to

court because John and his tenants had not been paying

taxes owed to him for use of the mill, which he had

previously sublet from Bordesley Abbey. As a result John

agreed that he and his tenants would pay the sum owed

and the claim for damages was dropped.

It is possible that this came about

because it was compulsory to use the manor’s mill, and

the tenants were trying to avoid payment by using hand

mills of their own.

John de Heronville died in 1315 and

the manor came under the control of the son by his first

wife, Henry. John’s widow Juliana was entitled to one

third of the estate for life (her dower) or until she

remarried. The document relating to the dower is an

important record, giving details of much of the estate.

It records several coal pits, and as such is the

earliest record of coal working in the town. Similarly

it contains the earliest record of ironstone mining in

the town. There are however, earlier records of coal

mining at Sedgley and Walsall.

|

| It seems that the 14th

century pits in Wednesbury were near Bradeswell,

possibly referring to Broad Waters. In some areas the 10

yard coal seam outcrops at, or very near the surface and

this is where the first coal would probably have been

extracted. In the 15th century Cockheath was

named as a coal mining area.

Juliana's share of the manor house included a hall,

pantry, a solar (a private room on the sunny side of the

house), a cellar beneath the solar, a brewhouse, a

bakery, stables, a cow house, and a long sheep house.

The buildings were arranged around a courtyard with the

hall and kitchen on opposite sides, and the solar and

bakery on the other sides. There was a well in the

centre, a gate house, an outer court, a garden and 2

yards. She also had her share of the dovecote, and 145

strips of arable land, part of John’s 120 acres. It

appears that these strips were interspersed with strips

belonging to the tenants in the common fields. The

document contains some of the field names, the first

time they were recorded. They are Monway Field, Church

Field, Hall Field, and Kings Hill Field.

Henry's share of the estate

included the manor house with courtyards and gardens,

120 acres of arable land, 10 acres of meadow (the common

land of the village), and a dwelling house formerly

belonging to Thomas Trond, with 15 acres of arable land,

including 2 acres of meadow. Henry was 50 at the time,

but only survived for another year, dying in 1316. His

son John Heronville II, aged 12 then inherited the

estate.

The taxes paid to the crown by the

nobility, clergy and laity were listed in the Subsidy

Rolls. The record for the year 1327 reveals that

Juliana, John’s widow, paid the highest tax in the town,

4shillings and 4¼pence, John Heronville II being absent

from the list. In 1332-3 Juliana paid 6shillings and

4¾pence and John paid 3shillings and 8¾pence.

The

Subsidy Rolls

The Subsidy Rolls of 1332 to 1333

include the names of individuals assessed for tax. Only

the richer members of society were eligible to pay the

tax, and although the list cannot be used to calculate

population figures, it does provide an indication of the

comparative size and prosperity of Wednesbury and the

surrounding towns. The amount of tax paid was based upon

the value of movable goods that were owned by each

person and the status of the town. People living in

cities, boroughs and ancient manors paid one tenth of

the value, whereas others paid one fifteenth of the

value. People whose movable goods were valued at less

than 10 shillings were exempt.

|

Subsidy Rolls

- 1332 to 1333

|

|

Town |

fraction of

value paid |

Number of taxpayers |

Amount paid |

Total value

of goods |

|

Bilston |

1/15th |

11 |

£1.3s.0d. |

£17.5s.0d. |

|

Birmingham |

1/15th |

69 |

£9.1s.4d. |

£136.0s.0d. |

|

Darlaston and Bentley |

1/15th |

12 |

£0.17s.0d. |

£12.15s.0d. |

|

Tipton |

1/15th |

9 |

£1.14s.8d. |

£26.0s.0d. |

|

Walsall |

1/10th |

25 |

£3.16s.0d. |

£38.0s.0d. |

|

Wednesbury |

1/10th |

13 |

£1.19s.1d. |

£19.10s.10d. |

|

Wednesfield |

1/15th |

14 |

£1.10s.0d. |

£22.10s.0d. |

|

West Bromwich |

1/15th |

11 |

£1.12s.0d. |

£24.0s.0d. |

|

Willenhall |

1/15th |

16 |

£1.13s.0d. |

£24.15s.0d. |

|

Wolverhampton |

1/15th |

30 |

£3.0s.8d. |

£45.10s.0d. |

14th

Century Court Proceedings

It seems that the relationship

between the Heronvilles, their tenants and the Hillary’s

of Bescot was becoming somewhat strained. In 1316 Thomas

Hillary sued 21 tenants from the manor of Wednesbury for

non payment of their dues for the mill, and claimed £100

in damages. The case was heard in the King’s court by

Sir Roger Hillary, lord of Bescot, and Chief Justice of

the Court of Common Pleas. The tenants admitted their

liability and the court decided that Roger was to

recover the money owed and collect 6shillings and 8pence

damages from each tenant. Roger Hillary then brought a

second case against 6 of his own tenants who had not

paid their taxes to the mill for 2 years, and claimed

£40 in damages. Once again the tenants admitted

liability and Roger recovered what was owed, and

collected 6shillings and 8pence damages from each

tenant. The mill remained as a corn mill until 1423 when

it became a fulling mill.

The Plea Rolls of 1337 offer

evidence to suggest that coal was extensively mined in

the area at the time. The document records that John

Walters of Wednesbury sued Sir Roger Hillary for taking

away "by force and arms" sea coal or "carbones

maritimos" to the value of £40 from his mines at

Wednesbury. In 1393 John Wylkys sued Roger Norton of

Darlaston for "digging and carrying away sea coal from

his several soil" at Wednesbury to the value of £10.

In 1344 at the manorial court in

Wednesbury, John de Alne was accused of being a common

robber after a break-in at John de Heronville's cellar,

at night, when items worth 17 shillings and 2 pence were

stolen. He was sent to Stafford to be detained until he

could be tried before the next gaol delivery. After

waiting 4 years, his trial took place before Roger

Hillary, who subsequently became Lord Chief Justice of

England. John de Alne was eventually sentenced to be

hanged.

The

Black Death

The late 1340s were terrible times

because of the onset of the Black Death, or plague as it

was known. It began in the wet summer of 1348 and large

numbers of people were rapidly dying. It continued

throughout the winter and became even more virulent in

the early months of 1349, continuing into 1350. It began

to return regularly, first in 1361 and again in the

1370s and 1380s. Large numbers of people died, greatly

affecting the working classes, possibly only ten percent

of whom survived. This would change the relationship

between the lord and his tenants and bring about an

early end to feudalism, in which the peasants had to

offer service with many obligations to their lord, in

return for a grant of land.

Peasants were now in short supply

and many farming communities disappeared. They now

wanted to dictate their own wage levels and terms of

employment. The rulers of the kingdom reacted strongly,

and within a year of the onset of plague, an Ordinance

of Labourers was issued, which became the Statute of

Labourers in 1351. This law attempted to prevent

peasants from obtaining higher wages, by ordering them

to accept wages at pre-plague levels. In reality the

high death rate meant that rents dwindled and much land

was uncultivated. Many villages were deserted and land

incomes fell. The rulers’ attempt to maintain the feudal

system failed, and before the end of the century the

working classes began to dictate their own terms and

freely move from one area to another, changing society

forever.

John

de Heronville III

John de Heronville II died in 1354

and was replaced by his son John, who married Alice, the

daughter of John of Tynmore. He bequeathed the manor of

Tynmore upon himself, his wife and their heirs, so

ensuring that the estate stayed in his family’s control.

At the time this action was illegal when carried out by

a tenant chief of the king, such as himself. As a result

he was ordered to pay a fine of 50 shillings to the

crown, which was equal to one third of the annual value

of the estate.

In 1366 John was sued by Sir Hugh

de Wrottesley for forcibly abducting one of his female

serfs. Seven years later John sued William Sagowe, a

chaplain, and Roger Hillary for abducting 4 men in his

service at Wednesbury. Both cases were possibly due to

the labour shortages following the Black Death. The

changes in the relationship between lord and tenant

possibly led John into a number of disputes with his

tenants, some of which ended up in the Royal Court.

|

|

Some of the local disputes involved

coal mining. In 1377 John Waters of Wednesbury sued

Roger Hillary of Bescot for taking coal to the value of

£40 from his mines at Wednesbury and in 1392 John Wylkys

sued Roger Norton of Darlaston for removing coal worth

£10 from his land. In 1403 John de Heronville’s second

son Henry took three tenants to court under the charge

that they trod down and consumed his corn and grass with

their cattle, and carried away earth to the value of

£10, which presumably refers to coal.

John de Heronville III died in 1406

and was survived by his three daughters, Joan aged 4,

Alice aged 2, and Margaret aged 12 months. They were

heirs to his estates at Wednesbury, Tynmore, and one

fifth of Tipton. As they were under age a guardian would

be appointed to look after them and also be custodian of

the manor. The guardian would be a close friend who was

not an eligible heir to the estate. John Ede in his

“History of Wednesbury” suggests that the first guardian

was John Brown of Lichfield, who was not very popular in

Wednesbury because in 1413 he had 4 men arrested for his

attempted murder. By 1415 John de Leventhorp became

guardian and it seems that he was also unpopular in the

town because Robert Nightingale, a coalminer, one of the

4 men already mentioned, attempted to murder him. He

also had problems with some of the tenants at Tynmore.

John de Leventhorp also seems to

have had problems with his tenants at Wednesbury due to

the changing relationship between tenant and lord as the

feudal system degenerated. In 1416 he obtained bonds for

£40 as security from coal miners Henry Hancocks and John

in the Lee, on the understanding that they would not dig

coal anywhere in the manor without his permission. In

spite of this measure they continued to dig coal much as

before and so later that year they were sued for a debt

of £40. During John’s time, relations between lord and

tenant reached an all time low and riots broke out. The

riots were probably about coal because John attempted to

protect his right to mine coal on his own land and also

to obtain a royalty from any tenant who mined it

elsewhere.

John de Leventhorp intended to keep

the manor of Wednesbury in his hands and this he did by

marrying Joan de Heronville to his eldest son William.

In 1418 he then persuaded the two younger sisters to

take the veil as nuns of the Order of Sempringham. As

nuns their share of the estate would pass to Joan, so

ensuring that William de Leventhorp became lord of the

manor of Wednesbury.

William and Joan had a daughter,

Elizabeth, and around 1435 William created a trust on

his land in Wednesbury, Fynchespath, Darlaston, and

Tipton so that if Joan outlived him she would be

entitled to the property for life, or until she

remarried. It would then pass on to their daughter

Elizabeth and her heirs.

Part of a map showing coal mines

in 1812.

Sir

Henry Beaumont

Some time before 1446 William had

died, and Joan married her second husband Sir Henry

Beaumont, who became lord of the manor.

Sir Henry Beaumont, lord of the

Yorkshire manor of Thorpe in Balme and second son of

Henry, the 5th Baron Beaumont came from a

distinguished family. His grandfather was a Knight of

the Garter, an admiral of the king’s fleet, and Warden

of the Scottish Marches and the Cinque Ports. His elder

brother was Constable and Great Chamberlain of England,

Knight of the Garter, and the first English Viscount.

Henry made a settlement of the

manor of Wednesbury (a complex arrangement for passing

on property) for his wife, himself and their heirs.

Henry and Joan had a son, also called Henry in 1446.

Unfortunately Henry senior died in the following year.

In 1452 Henry’s widow Joan resettled the manor upon

trustees, one of whom was Charles Nowell from Ellenhall

in Staffordshire. Charles became Joan’s 3rd

and last husband, and lord of the manor of Wednesbury.

Joan died some time after 1460, and her son Henry

Beaumont II became lord of the manor. Henry married

Eleanor, daughter of John, Lord Dudley and they had 1

daughter and 2 sons, the eldest, John, being born in

1470.

Henry’s reign ended on 16th

November, 1471, when he died. During his last year he

served as High Sheriff of Staffordshire. Before his

death he made a will leaving his land at Egington in

Derbyshire to his wife, and the remainder of his estate

to their son John. The will also expressed his wish that

his body should be buried in Wednesbury Church and that

a chaplain should celebrate mass for him for 3 years

after his death. He accordingly left 100 shillings to

the church, presumably to pay for the chaplain’s

services.

Eleanor’s son John married the

daughter of John Mitton of Weston in Staffordshire. They

had 3 children, Joan, Dorothy, and Eleanor. After his

death in 1502 the ownership of the manor passed onto his

3 daughters. Joan and Eleanor married two brothers,

William and Humphrey Babington, and Dorothy married

Humphrey Comberford, from Comberford near Tamworth. The

Beaumont estates were divided between the three sisters

as specified in their father’s will. Dorothy and her

husband Humphrey inherited Wednesbury, and their son

Thomas became lord of the manor. He also had estates at

Wigginton and Comberford. Most of

the old Wednesbury street and place names have

disappeared. The only street name that survives from

those olden times is the "Portway" or Portway Road. Some

place names from the old residential parts of the town

are still in use. They are Town End, Oakeswell End, Hall

End, and Bridge End. Near Bridge End is Finchpath and

the Ridding, another two of the old names. The High

Bullen was known as Hancock's Cross, possibly named

after the wealthy Hancock family.

The second most important residence after the manor

house was Oakeswell Hall named after a well, the Oakes

Well. William Byng built a house on the site around 1421

which descended into the Jennyns family. The adjacent

land, purchased by Thomas Hopkins and his wife was

called New Hall Fields. By 1662 the house became known

as Okeswell or Hopkins New Hall Place. In 1707 Richard

Parkes, ironmaster and Quaker purchased the house and

moved there in 1708. By 1774 it had become a farmhouse

and was occupied by the Kendrick family, and remained as

such until the 1820s. In 1825 the

house was owned by John Beaumont, a lawyer, and in 1846

it belonged to Walter Horton. It became known as "The

Rookery" and was later purchased by Wednesbury's first

Town Clerk, Joseph Smith, who greatly restored the

property. The house then came into the hands of Dr. G.

E. V. Morris and survived until 1962.

Oakeswell Hall. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Beginnings |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to the 16th Century |

|