|

Ironmasters with a pivotal role in the

industrial revolution

In an age of great figures whose

achievements made their mark upon the making of the modern

world, Sampson Lloyd II was one of the most influential, and yet

today is one of the least known. Matthew Boulton, James Watt,

William Murdock and Joseph Priestley still attract renown and

have statues to commemorate them, but in the years immediately

before they came to prominence, Lloyd played a pivotal role in

the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

Through his business as an ironmaster, he

provided the iron and steel that was so crucial for the making

of so many metal things. Then as the pace of economic change

gathered speed he provided another impetus through his bank,

Taylor's and Lloyd's, which loaned much of the money to power

manufacturing forward further and faster.

|

| Sampson's father, Sampson Lloyd I, had come

to Birmingham from Dolobran in Montgomeryshire as the 17th

century waned.

A Quaker, he was attracted by the town's reputation

for religious tolerance and also, it seems, by the

proximity of the family of his second wife, Mary nee

Crowley.

Her father, Ambrose Crowley II was a

remarkable man. A Quaker, he was born in Rowley Regis and was

the son of a nailer who owned moveable goods valued at £24 at

his death in 1680.

By comparison, Ambrose the second went on to

leave almost £1,200 when he died. His fortune had been made by

iron and it seems that the late 17th and early 18th centuries

were favourable times for enterprising and talented men from

humble beginnings such as he to wax wealthy. |

Ambrose Crowley II of Stourbridge

founded a dynasty of iron masters. |

|

Slitting mills

The rise of the Crowleys was spectacular;

so too was that of the Foleys. This family was responsible for

expanding industrial output in northeast Worcestershire and

south Staffordshire through the introduction of slitting mills.

This innovation was crucial to the massive growth in nail making

by hand. A piece of machinery with rotary cutters that was

worked by a water wheel, it cut (slit) thin iron sheets into

narrow strips and rods for nail making and other purposes. The

iron was made thin beforehand when a bar was hammered flat and

then squeezed even flatter between metal rolls in a rolling

mill.

According to an old story, Richard Foley

was a fiddler from Stourbridge who wished to learn about the new

slitting mills that had appeared in Sweden. He worked his

passage from Hull to Scandinavia and then paid his way to the

slitting mill by playing his fiddle. Here he became friendly

with the workmen and found out the mysteries of their trade.

Returning home he set up works with a partner, but as he had

forgotten some of the secrets on the long journey back he had to

make another expedition to fill in the gaps in his knowledge.

This he achieved and his mill was a great success and he became

wealthy.

Another story has Foley as a nailer who was

a drunkard who had his cow taken for his debts, after which he

went to Holland and returned with the invention of the slitting

mill. Such stories are embellished with fantasy but there is a

grain of truth in the recognition of Richard Foley as the key

figure in the introduction of slitting mills to England. His

importance is made plain in a most important book by Roy Peacock

called 'The Seventeenth Century Foleys. Iron, Wealth and Vision

1580 - 1716', which is published by the excellent Black Country

Society. Based on deep and thorough research, Roy brings to life the progress

of the Foleys. Richard himself was the son of a nailer from

Dudley. He became the most successful ironmaster of the age and

the slitting mill he set up on the River Stour from the late

1620s was vital to his ascendancy.

Foley was not the first person to open such

a mill in England, but he was the first to do so successfully

and in the long term. Henceforth more rods could be made more

cheaply and more quickly than slitting by hand. This allowed a

vastly increased output of nails, which were essential in an age

when so much was made of wood.

Based in Stourbridge from 1630, Richard

Foley built up a considerable undertaking so that by his death

in 1657 the family's ironworks accounted for over half of the

total iron production in the West Midlands and perhaps as much

as a quarter for the whole of England and Wales. Roy Peacock's

shows how Foley's children expanded their holdings into iron

making in north Staffordshire and the Forest of Dean,

gun-founding in the Weald of Kent, and into trade in London.

However by the early 18th century, the Foleys were moving away

from iron and into land - and as they did so other families such

as the Crowleys became pre-eminent in the making and trading of

iron.

|

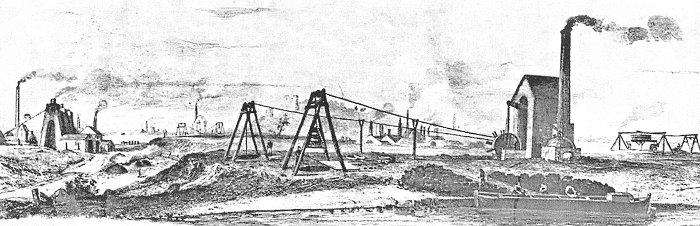

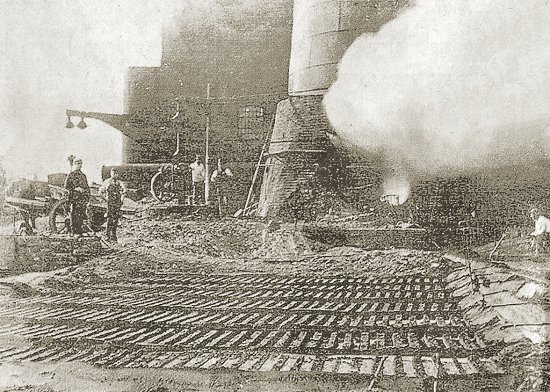

A Black Country blast furnace and

coal mines. The Lloyds were among the pioneers of blast

furnaces in the region at the Old Park Works in

Wednesbury, in 1825-26. |

|

Achievements

When Ambrose Crowley the second died in

1680 he owned a steel-making forge and an iron-making forge in

Stourbridge; he was an ironmonger of standing, putting out work

to a host of nailmakers and buying their goods from them to sell

on; he had a share in an iron works in Brecknock; and he was a

partner in a company that aimed to supply water to Exeter and

Barnstaple. These considerable achievements were surpassed

mightily by his son, Sir Ambrose. He shifted the nailmaking

operations to the north east of England and his trading centre

to London. So successful was he, especially in selling nails to

the Royal Navy, that upon his death in 1713 he left the vast

amount of more than £100,000.

Despite his move away from the West

Midlands and his undercutting of the prices of local

ironmongers, Crowley kept his interests in the Stour Valley and

he forged a strong link with Sampson Lloyd I. With little

experience of either manufacturing or trading, the Welsh migrant

to Birmingham soon became knowledgeable of both. He started up

as an ironmonger, fetching in iron from distant furnaces to sell

to local forges and slitting mills and then buying back from

them bar iron and rod iron to sell to putters out - the men who

supplied nailers and smiths.

|

|

Sampson Lloyd II - a leading

figure among iron masters. |

In this business Sampson I benefitted both

from the advice and custom of his brother-in-law, Sir Abraham

Crowley.

The knight bought rod iron from Lloyd for his slitting

mills to supply to nailers in the north of England, while

Crowley's mills in County Durham produced bar steel which was

distributed to edge tool makers in the Midlands by Lloyd.

With

no canals then to speed the movement of goods, it was a long

journey to Birmingham. The steel was taken by boat from the

north east to London and was then carried to the town.

This

expensive movement was made possible by the high value of steel

compared to its weight, as opposed to the lower value of iron. |

|

Sampson the first died in 1725. When he had

arrived in Birmingham it is said that he had nothing. This seems

unlikely given his background and close relationships with

wealthy families locally. Still, he may have had only 'modest'

means by middle class standards but through hard work,

integrity, and the development of family contacts with other

leading Quaker families he transformed his fortunes and became a

wealthy man, leaving £10,000.

His business was passed on to his eldest

son, Sampson II who had been apprenticed at a brass-wire firm in

Bristol where his father had an agent. The younger Sampson drove

forward the Lloyd's operations. If his father had laid the

foundations it was Sampson Lloyd II who successfully built upon

them and made himself one of the most influential businessmen in

the Midlands at an extraordinary time; the beginnings of the

Industrial Revolution.

His first wife, Sarah, was another

well-connected Quaker woman, for her father was Richard Parkes

an ironmaster from Wednesbury who had settled in Birmingham;

while his second wife, Rachel, was the daughter of Nehemiah

Champion, a Quaker merchant from Bristol with metallurgical

interests. Of their three daughters, Mary married Osgood

Hanbury, a Quaker merchant who had an extensive concern in

trading with the American colonies; and Rachel married David

Barclay, another leading Quaker merchant and also a banker.

Still, it was Sarah Parkes who provided what would become a

longstanding and crucial link between the Lloyds and Wednesbury.

Her father, Richard, had arrived in the

town from the Cotswolds in 1690 and like Sampson Lloyd I, his

rise to riches was greatly helped by a fortunate marriage - in

his case to Sarah, the daughter of Henry Fidoe. The son of a

small-scale ironmonger in Wednesbury, Fidoe became an active

Quaker with wide interests in the iron trade in Staffordshire.

It would seem that as Sir Ambrose Foley had

helped Samson Lloyd I, so too did Henry Fidoe help his

son-in-law, for Richard Parkes went on to become one of the

biggest customers of the Foleys. Parkes then built on these

strong foundations and invested in the future by buying land and

buildings in and around Wednesbury. Most importantly he also

purchased local surface and mining rights.

These latter weren't much exploited during

most of the 18th century, simply because of the inability to

effectively pump out the water that flooded deeper coal and

other mines. But the development of the steam engine transformed

this situation and made mineral rights a most valuable

possession.

Its potential for creating wealth was

recognised in the early 19th century by Samuel Lloyd II Known

popularly as Quaker Lloyd, he inherited the Parkes properties,

and then in 1839 added to them with 108 acres that came to him

through his Fidoe ancestry. It was by this connection that

eventually the great firm of F. H. Lloyd would be set up in the

Black Country.

That was in the future, for now in the 18th

century the Lloyd's affairs grew rapidly under the guidance of

Sampson the second. It was he who created what would be regarded

today as an integrated structure of businesses. Pig iron came

from a blast furnace at Melbourne in Derbyshire, while it was

converted into bar iron at Burton upon Trent, and the family

owned another forge at Powick near Worcester. This bar iron was

then taken to Lloyd's slitting mill at Birmingham, which had

been bought in 1728 by Charles Lloyd, the older brother of

Sampson II.

The first proper plan of Birmingham dates

to three years later. It shows Lloyd's slitting and corn mills

on the corner of Lower Mill Lane and what would become Bradford

Street. It was in a most prominent position with easy access to

the important through-route of Digbeth and was powered with

water from the nearby River Rea. This mill came into the

ownership of Sampson II in 1741 after his brother died.

|

| Bull Street, Birmingham, in

1956. The Minories is on the right and the Friends

Meeting House and burial ground was further up, just

before the building that juts out.

The Friends still meet on

virtually the same spot as they have done since 1703.

This is where the Lloyds,

Parkes, Fidoes, and Pembertons met to worship. |

|

| In Stourbridge, the local

Friends gather in an older meeting house leased to them

in 1689 on a peppercorn rent by Ambrose Crowley II. |

|

Wealth

Fourteen years afterwards it was described

in 1755 by some Londoners who visited the Pembertons, close

relatives of both the Lloyds and Fidoes and another Quaker

family that made its wealth from iron. It was: "too curious to

pass by without notice. Its use is, to prepare Iron for making

nails. The process is as follows: They take a large iron bar,

and with a huge pair of shears, worked by a waterwheel, cut it

into lengths of about a foot each; these pieces are put into a

furnace, and heated red-hot, then taken out and put between a

couple of steel rollers, which draw them to the length of about

four feet, and the breadth of about three inches; thence they

are immediately put between two other rollers, which having a

number of sharp edges fitting each other like scissors, cut the

bar as it passes through into about eight square rods; after the

rods are cold, they are tied up in bundles for the nailor's

use".

Lloyd's workers also produced bar iron,

which was used by smiths across the land to make a wide range of

iron goods, and steel for the cutlery, blade and edge-tool

industries. On top of this Lloyd acted as an ironmonger, selling

the finished goods of smiths and nailers to London markets

especially.

|

A Black Country scene that was

familiar in the latter 18th century - mines, machinery,

steam and canals. |

Sampson Lloyd II was a leading figure among

the great names of a dynamic, exciting and sometimes confusing

era that changed the world,

He was a contemporary of Matthew Boulton, perhaps the

most famed industrialist of the age, and joined with him

and others in supporting the cutting of the Birmingham

Canal.

From its full opening in 1772 this linked the town

with the coal and iron deposits in the Black Country.

|

|

It was the first of the canals that soon would

enable Birmingham's manufacturers to reach the world

more easily through readier access to ports such as

London, Bristol and Liverpool.

A self-effacing man, Sampson Lloyd II was

also a pivotal figure in the banking revolution that was so

crucial to the Industrial Revolution, by way of providing the

finances for the rapid expansion of manufacturing. In 1765 he

and his eldest son, Sampson III, joined with John Taylor the

Brummagem button king and his son to found the first real bank

in Birmingham - that of Taylor's and Lloyd's.

Their premises were in Dale End and are

remembered today by a blue plaque placed by the Birmingham Civic

Society, and indirectly Sampson Lloyd II had a major impact on

the growth of Wednesbury in the 19th century through the

legacies of his father-in-law, Richard Parkes, and of his Fidoe

cousins. Ultimately they led to the arrival in the town of

Sampson's great grandson, Samuel Lloyd II who would go on to

establish one of the chief ironworks in the Black Country; while

his great, great, great grandson, Francis Henry, would found the

celebrated company of F. H. Lloyd, a name that resonates still

with pride for the folk of Wednesbury and Darlaston especially.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|