|

Master of steel, master of town

F. H. Lloyd was one of the great

manufacturing enterprises not only of the Black Country but also

of England. Acclaimed as 'masters of steel', the company was

famed for its large castings - but like many successful

enterprises it had begun in a small way.

After the failure of his family's Darlaston

Iron & Steel Company in the Depression that fell upon England in

the later 1870s, Francis Henry Lloyd set up a small foundry in a

disused timber yard at James Bridge. Although located toward the

edges of Darlaston and having a Darlaston telegram address, F.

H. Lloyd always advertised the James Bridge Steel Works as near

Wednesbury because of the historic links between his family and

that town.

Ironstone

Of course the Lloyds were best known as

the co-founders of Taylor and Lloyd's Bank, but they had made

their money from a mill for slitting iron close to the Bull Ring

in Birmingham. Then in 1818, Samuel Lloyd the second had gone to

live in Wednesbury to look after the family's interests in local

coal and ironstone mines and clay pits for bricks and tiles.

However it was F. H. Lloyds that was to

have a more profound effect on the town and indeed the Black

Country. In the early twentieth century the company began making

small steel castings and in the Great War it produced a great

amount of cast steel shells. Then in the 1930s, F. H. Lloyds

began to make heavy castings for mechanical excavators and

earth-moving machines and in 1938 it installed its first

electric arc furnace.

|

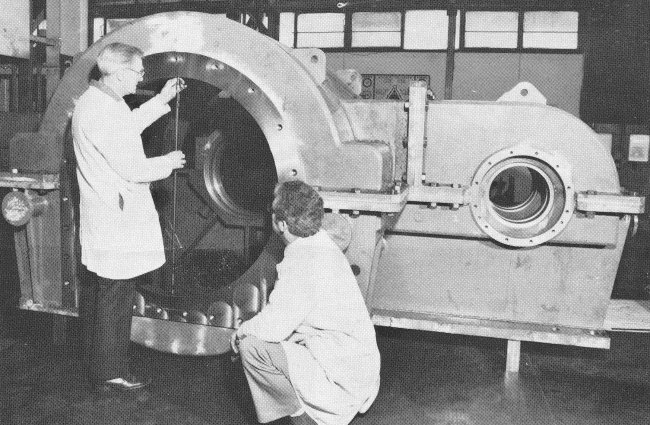

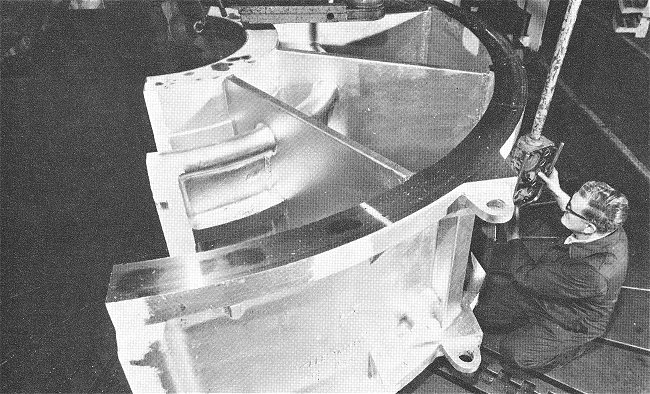

The final inspection of a turbine

gear housing that was cast at the factory. From the

August 1975 edition of 'The Steel Casting'. |

|

Such developments ensured that the firm

played an even more important role during the Second World War

than it had in the Great War. It manufactured approximately 80,000 tons of finished steel castings.

This total included 2,000 turrets for the Churchill tank and

8,000 tons of bomb body castings.

Two outstanding features of wartime

production were the importance both of female workers and

training. Another was the loyalty of a skilled, experienced and

motivated workforce. This was a characteristic that had marked

out the Lloyd companies in the Black Country since the time of

Quaker Lloyd and it was remarked upon several times in the 1950s

by the chairman and managing director, F. N. Lloyd.

Expansion at the James Bridge Works

continued into the 1960s with a new heavy foundry and a 30-ton

melting furnace. The company became renowned for its heavy

castings, and despite often difficult trading conditions, it

thrived and took over businesses elsewhere.

In 1970 it was even featured in the

'Guardian' because of its fabrication of five steel frames that

would form the body of a 5,000-ton hydraulic press that would

produce concrete slabs 20 feet by 10 feet and 10 inches thick.

Each frame weighed 30 tons and was also machined at Wednesbury.

In 1975, the steel industry in the United Kingdom had about 70

firms and 90 foundries, many of which were small. Consequently

the bulk of output was from foundries that produced more than

1,000 tons a year. In fact, four firms dominated the industry,

accounting for 55 per cent of output by value.

The largest of them all was F. H. Lloyd of

Wednesbury, which produced almost 23,000 tons a year. It was an

astonishing achievement but sadly the end was nigh.

The later 1970s brought major economic

problems and a rapid decline in the demand for steel. Short-time

working at the foundries was brought in during 1980 and sadly

two years later the historic firm that was so linked with

Wednesbury was felled by a recession which overwhelmed so many

great manufacturing names in the 1980s. Gone it may be but the

skills and talents both of the Lloyds and their workers should

never be forgotten.

|

|

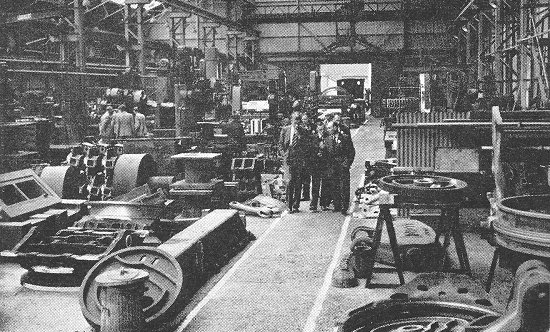

The machine shop where John Harper

worked. |

One of those who has not forgotten

is John Harper.

After leaving school in 1958, he began work as an

engineering apprentice at F. H. Lloyd's when it was in its

heyday.

By then it employed about 3000 people and took on around

40 apprentices annually. John takes up the story:

|

|

Fifteen were engineering apprentices

destined for the machine shop; fifteen were foundry apprentices

and ten were maintenance apprentices, all of whom were five year

indentured apprenticeships. Jim Whitehouse's son, Brian,

subsequently became Inspection Department supervisor later on.

In addition and on a part-time basis the legendary Bert Williams

trained the football teams, and Eric Shipton, a member of the

successful 1953 Everest expedition, assisted with the early

Mount Snowdon forays.

The engineering apprentices spent the first

122 months at the engineering training centre, approximately

half a mile from the main works at Bourne House, situated on the

Walsall Road. A typical day was spent thus: 7.30 am change into

shorts, vests and plimsolls and run down to the sports field in

Park Lane for half an hour of hard physical training under the

beady eye of Jim Platt, physical training instructor.

Then run back to Bourne House, shower and

into the lecture room for engineering theory, followed by half

hour lunch then into the training machine shop for practical

instruction under the engineering instructor Fred Naylor. Fred

was of a smallish build, a softly-spoken man, but was one of

those people that imparted his knowledge with a quiet authority

that commanded respect. In addition, apprentices were allowed

one or two days release to study at the local Technical College.

|

Mr. Lloyd at the Hilton Valley

Railway. John was involved in the construction of the

engine. From the Christmas 1958 edition of 'The Steel

Casting'. |

A major project that was carried out at the

training centre was the complete construction of a model steam

engine, Francis Henry Lloyd. Began in 1959 by Trevor Guest and

later by Fred Naylor and FHL apprentices, many of the components

were cast in the foundry training centre, then machined and

subsequently assembled by the engineering apprentices.

The locomotive was a 7.5 inch gauge,

roughly eight feet long with the tender, and was destined upon

completion for Mr. M. C. Lloyd, who was joint managing director,

and the track and loco were installed in his huge garden at his

home in Hilton Valley, Shropshire. The project took a

considerable time to complete, and each intake of apprentices

would have the chance to work upon it. The loco, which is still

in existence, was bought by the Eastleigh Lakeside Steam Railway

and is still operational.

When the locomotive was installed at Hilton

Valley, occasionally Fred Naylor would take perhaps six of us at

a time to undertake maintenance on site at Mr. Lloyd's house. It

was a thing which we all enjoyed immensely due, no doubt, to the

fact that MC's garden contained apple, pear and fruit

orchards, which, naturally, we took advantage of. |

|

We were transported from

the works to Hilton Valley in a twelve-seater Austin van by a

man named Archie Trevor, who at that time was in his late

fifties, and whose usual job among other things was to transport

the firm's various sports teams to sports fixtures and events at

other companies.

After 12 months in the training centre, we

were absorbed into the huge machine shop, which comprised of

three bays. The smallest of these was the "bomb bay", named as

such because it was used primarily for shell casing production

in World War Two and housed the smaller milling machines, lathes

and vertical borers. Each apprentice was allocated to a machine

operator for six months at a time. At the same time as learning

to operate the machine, it was part of the apprentice's duty to

keep the machine clean and free from swarf, which is the metal

that is removed from the casting by the machine tool.

I was first assigned to a huge brake lathe.

The chuck, the part that turns in the lathe was roughly six

feet in diameter, and the overall length of the lathe was

probably 15 feet. The operator was a small, good humoured,

skilled man name Sid Causer, and I got on well with him. It was

my job to remove the swarf.

The machine shop had many characters, one

of whom was a man named Billy Ray, who operated a huge vertical

boring machine with twin tool pillars. The machine had at floor

level, a circular steel table, some 22 feet in diameter which

rotated at a controlled speed when in use, and was straddled by

a bridge from which hung two tool pillars. When a casting,

usually a turbine casing shaped like a half cylinder, perhaps 12

feet in diameter and 10 feet tall, 25 or 30 tons in weight, was

centred and secured on the table, it would slowly rotate and it

was machined on the inside half diameter by means of two tools

fixed to the tooling pillars. This meant that because it was a

half cylinder, one tool was always in contact with the surface

to be machined, whilst the other was in mid-air.

Fear

I have tried to illustrate this because

Billy Ray, a larger than life character, would be standing on a

pair of decorator's steps on the turntable, watching and making

sure that the casting was being machined correctly.

Unfortunately, this meant that Billy's head was reversing toward

the approaching tool and just as it looked like curtains, Billy

Ray would instinctively duck! It used to put the fear of God

into me to watch.

Many of the lads that I worked with at FHL:

George Hall, worked with the aforementioned Billy Ray. John Hall,

Mick Jones, Ronnie Arnold, Freddie Clarke and Archie Deeley,

still keep in touch, and we meet up every couple of months or so

at St. Mary's Club, Wednesbury.

The machine shop holds an annual get

together at the Royal British Legion Short Heath, and after all

these years is still well attended. It is organised by another

larger than life character, held in high esteem by all who know

him, Ernest Arthur Wright, or "ee ay right" as he is

affectionately known by his workmates, and assisted by another

machine shop employee Peter Jenkins.

Horrendous

After my apprenticeship I transferred to

the Inspection Department in the heavy dressing shops at F. H. Lloyd, One of the

heavy dressing shops was bay 8 situated at the James Bridge end

of the works and the other being the largest which was situated

where Wednesbury IKEA now stands, and was known as Bay 150.

|

|

The dressing shops received the raw

castings from the foundries, covered in concrete like sand, and

were processed by hydroblasting and shotblasting to remove and

clean them of sand, and subsequent "dressing", i.e. removal of

excess metal and defects by men in protective clothing using

pneumatic chiselling hammers and heavy duty grinders.

The noise

produced was horrendous, and most communication was done by sign

language.

In Bay 8 many of the castings were

tank turrets and panniers, (the sloping part at the

front of the vehicle where the driver sticks his head

out), for the Chieftain and Challenger main battle

tanks, and when the castings were completed it was the

job of the Inspection Department dimensional inspectors,

(markers out), to ensure that they met the required

dimensional specification.

|

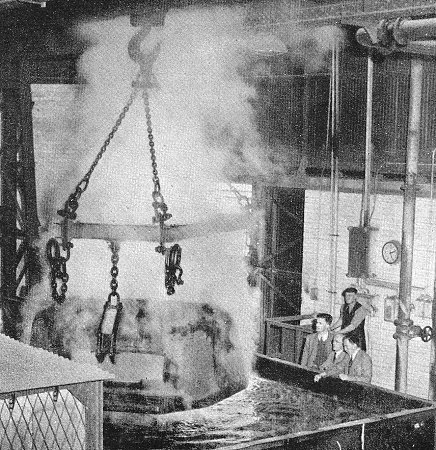

The seven and three quarter tons

turret of a Centurian tank emerging from the 18 foot

quenching tank. The onlookers are Mr. F. N. Lloyd,

Arthur Reynolds, supervisor of the heavy heat treatment

department, and Jim Pestridge a BBC outside broadcaster. |

| This was done by levelling the casting on hydraulic jacks on a huge cast iron

table, painting them white with a water and hydrated lime paint,

then when it was dry the marker out would scribe lines on the

casting using steel height gauges to ensure there was enough

machining stock and that the various dimensional features were

correct to the engineering drawing. One of the lads I worked with for many

years at FHL was a guy named Harry Parry, who worked his way

through the ranks and attained a senior position in the

Inspection Department. Harry was, and is, endowed with a roguish

sense of humour, and I remember one "Open Day" when visitors

were allowed a tour of the works, an elderly gentleman enquired

of Harry, "Young man, why do you paint the castings white?"

Quick as a flash Harry replied "So the night turn don't trip

over 'em!" |

|

A Chieftain tank on display at a

works open day. |

|

In Bay 150, the heavy turbine casings were

processed. FHL produced steam turbine casings for major

electricity generating companies, such as C.A. Parsons and GEC,

and in addition for hydro-electric casings and Kaplan blades for

Markham's of Chesterfield. Markham's produced the hydroelectric

turbine generating equipment for the Dinorwic pumped

hydroelectric power station at Llanberis, north Wales.

Kaplan blades, designed and developed in

1913 by the Austrian professor Viktor Kaplan, are the four

blades fitted into the hub that spins at high speed when high

pressure water is directed at them. In a conventional turbine

the blades are turned by steam. The blades are a complex shape,

each being similar to a single blade of a ship's propeller, and

have to be made to strict dimensional tolerances, and due to the

complex shape, it was not possible to produce the required form

by conventional machining methods.

In the 1960s, this was

achieved by levelling the blade, which was roughly 12 feet by 10

feet wide, and weighing about 5 tons on the marking off table.

Then a large steel box form template made to the correct form

would be lowered by a crane hoist until it just touched the

casting. The marker off would mark on the blade where it

touched, then the template would be removed and the dressers

would remove material with pneumatic chipping hammers and

grinding wheels. The whole process would be carried out again

and again until the required shape was attained when the

template touched everywhere. Hard graft by any standards. This

process took many weeks, and must have cost a fortune. Today

this would be done in a few days using CNC computer-controlled

machines.

|

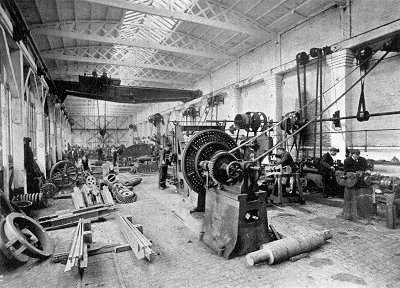

An early view of the Machine Shop,

where John served his apprenticeship. |

In addition to the above, F. H. Lloyd

produced huge and complex castings for heavy industry, the

Ministry of Defence and many major civil engineering projects

such as the Humber Bridge, the Thames Barrage, usually wrongly

called the Thames Barrier, and most of the UK power stations,

whether coal, oil or nuclear powered.

Usually on a car or coach

trip if we pass one of the above projects, my wife Kath will

say, "Don't tell me, made at FHL!" The answer is usually yes, it

was. |

| Sadly, one of the last projects that FHL

produced castings for, was for replacement components for the

Atlantic Conveyor transport ship, lost during the Falklands War

in 1982. F. H. Lloyd was a superb company to work for, and the

sports and social activities were second to none.

Employee

welfare was paramount. F. H. Lloyd had a first class medical

centre, led by the indomitable Sister Powell and her team. The

medical centre was a vital part of the operations, because, due

to the heavy industry that FHL was engaged in, injuries were

frequent, and though usually minor, there were a number of

instances of men losing limbs, and there were a number of

fatalities. One occurred in the heavy dressing shop in Bay 8

where I worked for a time. Such tragedies were thankfully

extremely rare, and FHL had generally a good reputation for safe

working practices at that time.

There were Christmas parties and

presents for employees' children, employees' long service

awards, and apprentices' awards. All of the catering and lavish

decoration was carried out by canteen manageress Mrs Parry and

her team. There was an annual horticultural day held at the

sports field in Park Lane, and there were camping and climbing

expeditions to Snowdonia for the apprentices. |

|

Inspecting a casting for the top

half of a G.E.C. 50 MW gas turbine main casing. |

|

The manager or chief inspector of the

Inspection Department that I worked in was Colin Woolhouse, an

ex-army military policeman, and didn't he let us know it! If it

was your turn for a telling off, usually deserved, Colin would

make sure you got it! I never had any hard feelings though and I

always held him in the highest regard. His wife, Marion, worked

in the medical centre.

F. H. Lloyds, although still making a

profit, announced closure in 1983 due to the "rationalisation"

of the steel casting industry. I received a first-class

technical apprenticeship at FHL, and all of the heads of

departments and managers were time-served experts in their field,

from the design engineers, methods engineers, pattern shop,

foundries, dressing shops and the machine shops, and it was a

pleasure to hear them discussing problems and the technical

expertise that they utilised to overcome them.

What I learned and experienced from my time

there stood me in good stead, and I never had a problem getting

a job post FHL. I was 63 when I was taken on by my last

employer, the Brockmoor Foundry at Brierley Hill, one of the few

remaining successful privately owned foundries in this region.

After reaching 65, I stayed to work part time until I was 68 in

2010, when I had to retire through ill health.

With the demise of companies such as F. H.

Lloyd's, and the subsequent loss of skills, I wonder who is

going to train the apprentices of tomorrow that politicians are

now realising are central to the UK's manufacturing base and

future prosperity. Superb company, and a superb time to be

growing up through the 50s and 60s as witnessed by the lifelong

friends that I made there. I just wish my grandchildren could

have the same opportunities.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|