| The

1916 Zeppelin Raids. By Bev Parker |

|

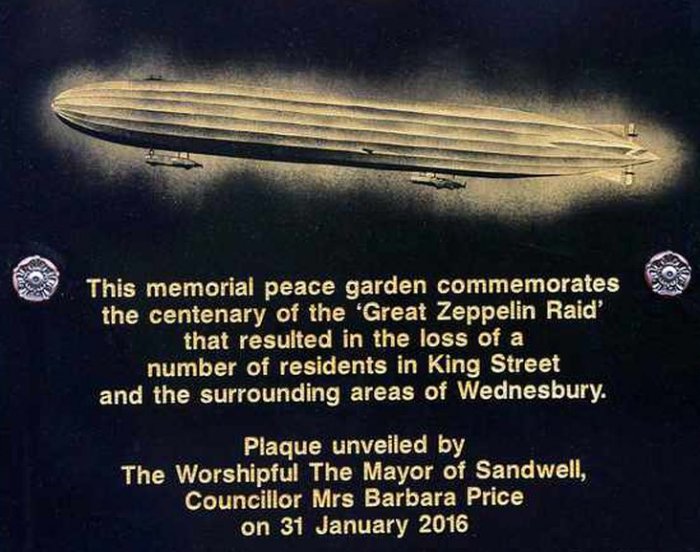

On 31st January, 1916, seventeen

months into the First World War, the Black Country

unexpectedly experienced the might of the German armed

forces at first hand, when two Zeppelins carried out

bombing raids, and terrorised the civilian population.

The German military were getting

increasingly confident after several raids on the east

coast and London, and planned an audacious attack on

Liverpool involving nine Zeppelins, and a flight of over

130 miles across England. The airships left their bases

on the afternoon of 31st January for a round flight of

nearly 1,000 miles, and initially everything went well.

The North Sea was crossed without incident, but on

reaching Norfolk they encountered mist and fog, and were

soon hopelessly lost. Airborne navigation relied on

observation and careful plotting on maps, recording air

speed against time. All that they could rely on was an

occasional break in the fog.

Two of the airships, L21 and L19

both made the same navigational error, and ended up over

the Black Country. The first to arrive, L21, was

captained by 45 years old Max Dietrich, an uncle of the

famous singer and actress, Marlene Dietrich. The vast

Zeppelin must have been an awesome sight. It was just

over 536 feet long, and 61 feet in diameter. It had a

top speed of 60 mph.

|

|

Landing a Zeppelin. From an old postcard. |

|

Using his maps, Dietrich plotted

his way across the country, soon hoping to see the

lights of Manchester, followed by Liverpool and the

Mersey. At 5.25pm. the L21 was spotted above King's

Lynn, and was seen over Derby at 6.55pm. News of the

airship's approach had already reached Derby and so the

town was blacked out. L21 then crossed Rugeley and was

spotted above Merridale Lane, in Wolverhampton at half

past seven. The airship then turned southwards to cross

Wombourne,

Kingswinford and Brierley Hill.

As Dietrich reached the Black Country, he saw lights,

and reflections, possibly from one of the many canals,

and assumed that he was near his target. The crew was

ready, and bombs were prepared for dropping. As the

airship passed over Netherton, Dietrich spotted William

Grazebrook's Ironworks and a bomb was dropped, but it

completely missed its target. L21 then turned northwards

and crossed Dudley before arriving at Tipton around

8.00pm. More lights were spotted

and the carnage began. The L21 arrived on a foggy and

frosty night above Tipton. Three high-explosive bombs

were dropped on Waterloo Street and Union Street,

destroying two houses, damaging several others, and

setting a gas main alight.

That evening the ‘Tivoli’ Cinema in

Owen Street was full to capacity. Around 1,400 people

were watching the film when the bombs started to fall.

One member of the audience, Thomas Morris, suffered

terribly. Earlier that evening his wife Sarah Jane had

taken his children to visit her mother in Union Street.

When Thomas heard the nearby explosions, he immediately

made his way to Union Street, only to discover that the

house had suffered from a direct hit, and was completely

destroyed. Inside he found the bodies of his wife, his

children, and his parents-in-law. Three generations of

the family were dead. It’s hard to imagine Thomas

Morris’s agony and despair at the time.

Fourteen people

were killed at Tipton, five men, five women, and four

children.. They were:

Thomas Henry Church aged 57, estate

agent at 111 Dudley Road was inspecting a property in

Union Street.

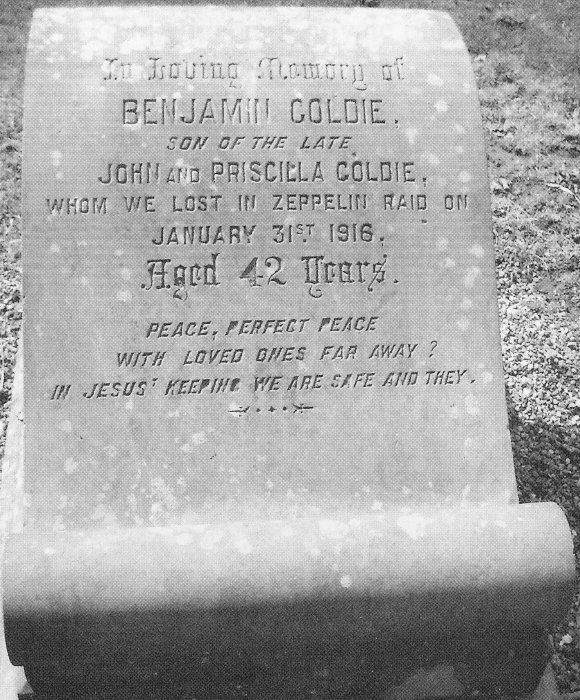

Benjamin Goldie aged 42, of 58

Queens Road ran the family's iron fender factory in

Albion Street.

Daniel Whitehouse aged 34, died

whilst standing at his mother's front door.

Arthur Edwards aged 26, shoemaker

died in the family shop at 69 Union Street.

Annie Wilkinson aged 44, 16 Union

Street. Her husband George was injured.

Elizabeth Cartwright aged 35, of 1

Coppice Street. Died on the footpath.

Louisa York aged 30, a nurse from

Waterloo Street, was standing in an entry.

Frederick Norman Yates aged 9, was

badly injured in Union Street and died in a nearby

doctor's surgery.

George H. Onions aged 12, was

walking in Union Street.

Martin Morris aged 11, Nellie Morris aged 8, Sarah Jane

Morris aged 44, and parents-in-law Mary Greensill aged

67, William Greensill aged 64, all died at 1 Court, 8

Union Street.

|

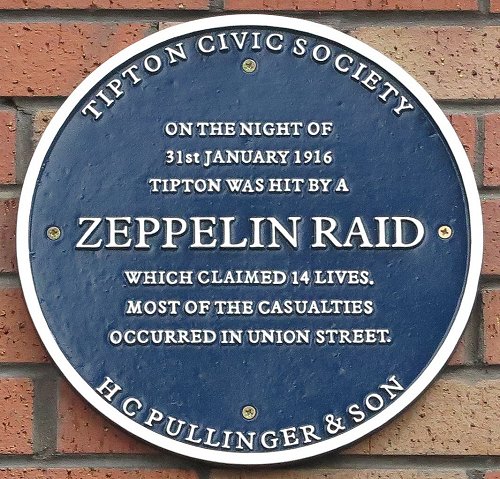

The blue plaque that

is

on a shop front in Union Street, Tipton. |

In Tipton Cemetery there is Benjamin

Goldie's memorial stone and several mass

graves including the Morris and the

Greensill families. The L21 then dropped two bombs on

the railway station in Owen Street. They landed between

the station and the canal towpath, causing extensive

damage. |

|

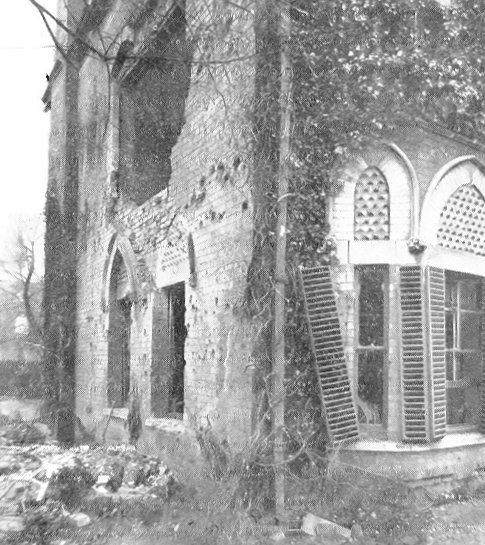

Some of the

destruction. From Lloyd's News, 13th

February, 1916. |

|

Another image from

Lloyd's News, 13th February, 1916. |

|

Another image from

Lloyd's News, 13th February, 1916. |

|

Another image from

Lloyd's News, 13th February, 1916. |

| A final image from

Lloyd's News, 13th February, 1916. |

|

|

|

The remains of houses in Union

Street, Tipton. |

| The airship then flew over

Bloomfield Road and Barnfield Road, dropping incendiary

bombs on the way. Three landed in gardens in Bloomfield

Road and failed to ignite and three were dropped on

Bloomfield Brickworks. L21 then continued

northwards to the canal at Bradley, where a young

courting couple had gone for a stroll. William Fellows,

aged 23 from Coseley, and his 23 years old girlfriend

Maud Fellows from Bradley, were walking along the

towpath near to Bradley pumping station. They took

shelter when they heard the roar of the oncoming

airship. As it approached, the crew would have seen the

lights around Bradley, and so the bombing started again.

Sadly one of the bombs landed near to the young couple,

killing William outright, and fatally injuring Maud, who

was taken to the 'Old Bush Inn' where she received first

aid. From there she was taken to the Wolverhampton and

Staffordshire General Hospital, where she died of

septicaemia on 12th February. Their deaths are

commemorated by a small plaque on the pumping station

wall. |

|

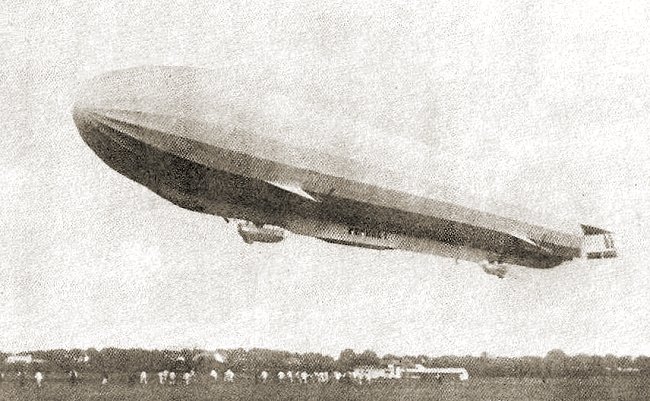

A Zeppelin in flight. From an old

postcard. |

|

After crossing the canal, the

Zeppelin travelled eastwards towards Lea Brook and

Wednesbury. Dietrich would have seen the lights of

Wednesbury in the distance as the airship crossed over

the dark area of Lea Brook. A possible glimpse of the

canal could have convinced him that he was finally

reaching Liverpool. Around 8.15 that evening he headed

towards the brightly lit town centre and soon reached

Russell’s Crown Tube Works, where the bombing

recommenced. The incendiary bombs set the huge factory

alight, leaving a burnt-out shell, parts of which

remained until the 1960s.

King Street ran alongside Crown

Tube Works, and was the site of the next atrocity. The

Smith family, who lived at number 14 King Street were

greatly troubled by a loud noise near their home. Mrs.

Smith left the house to investigate, and soon saw a fire

at the works, which she assumed to have been caused by

an accident in the factory. She turned round and headed

back home, but by then the airship had moved over the

factory and dropped another bomb, which completely

destroyed number 13, and badly damaged number 14,

instantly killing her family. Later that night the

bodies of her husband Joseph Horton Smith, aged 37, her

daughter Nellie, aged 13, and her son Thomas, aged 11

were found amongst the ruins. The body of her other

daughter Ina, aged 7 wasn't found until the next

morning. She had been blown onto the roof of the tube

factory.

While the bombs were falling, the

audience at the King’s Hall, in Earps

Lane were enjoying a melodrama. Luckily the

explosions had fractured a gas main, which plunged the

town centre into darkness. The audience first realised

that something was wrong when they heard the explosions,

and the lights went out. They hurriedly left the theatre

and saw the huge Zeppelin, hovering above the burning

factory.

|

The remains of the outer walls of Crown

Tube Works in King Street, Wednesbury after the 1916 Zeppelin

raid.

The bomb damage at number 14 and number 13

King Street, Wednesbury. From a magic lantern slide. |

Another view of the damage in King

Street. From the Illustrated London News, 12th February,

1916. |

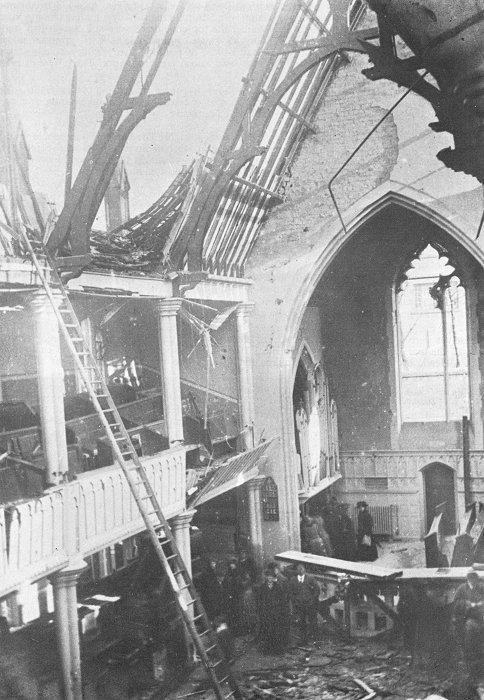

The interior of Wednesbury

Road Congregational Church. From an old postcard. |

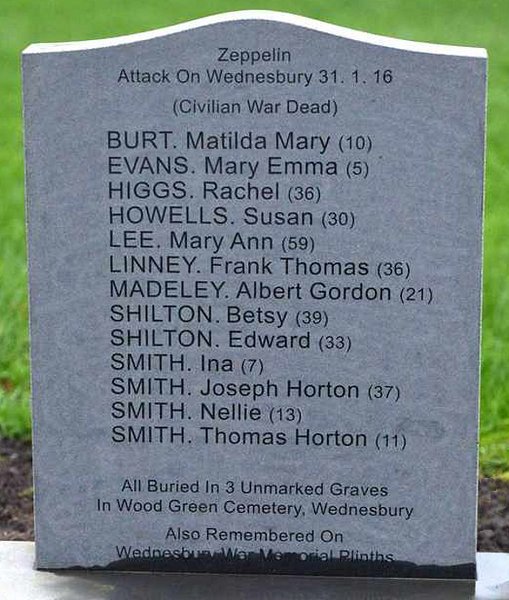

Other bombs were dropped near

to the Crown and Cushion pub, in High Bullen, before

the Zeppelin moved away. Another thirteen people had

been killed, four men, four women and five children.

There is now a memorial to them in Wood Green

Cemetery. It has the following names:

Matilda Mary Burt aged 10, Mary

Emma Evans aged 5, Rachel Higgs aged 36, Susan

Howells aged 30, Mary Ann Lee aged 59, Frank

Thompson Linney aged 36, Albert Gordon Madeley aged

21, Betsy Shilton, aged 39, Edward Shilton aged 33,

Ina Smith, aged 7, Joseph Horton Smith, aged 37,

Nellie Smith, aged 13, and Thomas Horton Smith, aged

11.

L21 then headed in a north

easterly direction towards the lights of Pleck and

Walsall, dropping more bombs in Brunswick Park Road.

The next bomb was dropped on Wednesbury Road

Congregational Church, badly damaging the building.

At the time a preparation class from a local primary

school was at work in the church parlour.

Fortunately the parlour survived, only a small piece

of the ceiling fell into the room. Unfortunately Mr.

Thomas Merrylees aged 28, who was walking past the

church at the time, wasn’t so lucky. A piece of

flying rubble removed the top of his head, instantly

killing him. |

The church interior after the bombing.

|

The General Hospital and the

Congregational Church. From an old postcard. |

|

A short time later, an incendiary

bomb fell next door, in the grounds of the General

Hospital, which was quickly extinguished by a passing

policeman, Constable Joseph Burrell, who was on his beat.

He heard a strange sound and looked up to see the

Zeppelin overhead, dropping bombs as it went on its way.

He saw the two bombs that were dropped on the

Congregational Church about 80 yards away. Luckily his cape

helped to protect him from falling debris, and so he was only slightly injured. He then

saw flames coming from the hospital grounds and so

rushed inside to see an incendiary bomb burning between

the men's and women's wards, and managed to extinguish

it using a piece of wood. Afterwards he calmed the

patients and staff. The hospital later presented him

with an inscribed medal for his bravery. Because of the

heat from the burning bomb, his eyes were badly

affected. He went blind in 1924 as a result of his

injuries.

Another bomb damaged houses in Mountrath

Street, and another blew a hole in the wall of a saddle

maker’s workshop at the factory of Elijah Jefferies &

Sons Limited.

|

Wednesbury Road Congregational

Church after the bombing. The notices state that the

next service will be held in the Temperance Hall in

Freer Street. From an old postcard. |

|

Another view of the bomb

damage. From an old postcard. |

|

Minutes later the L21 flew over

Bradford Place and dropped a final bomb outside the

Science and Art Institute in which many students were at

work. Only one of them, Mr. A. K. Stephens, who was

attending a chemistry class, suffered any injuries. He

was badly cut, possibly by flying glass, and treated in

the hospital.

Things weren’t so good outside. The

bomb wrecked the public toilets, and damaged tramcar

number 16, in which one of the passengers was the Lady

Mayoress of Walsall, 55 years old Mary Julia Slater,

wife of Samuel Mills Slater of Bescot Hall. She received

severe injuries to her chest and abdomen, from which she

never recovered. Sadly she died in hospital from shock

and septicaemia on February 20th. Three other people were

killed in the blast, and many were injured. The three

who died were Charles Cope aged 34, William Haycock aged

50, and John Powell aged 59.

|

Tramcar number 16 in which

Mary Julia Slater was travelling. The broken windows

from the explosion can clearly be seen. |

| The memorial to Mrs Slater,

and the shrapnel-damaged wall in Bradford Place. |

|

|

From the

Wolverhampton Chronicle, 23rd February, 1916:

Inquest on the body of

Midland Mayoress

At an inquest held on

Tuesday respecting the death of the Mayoress of

a Midland town, a victim of the Zeppelin raid,

evidence was given by the Mayor that he was

called to a certain street on Monday, January

31st. He saw his wife in a shop, having

sustained certain injuries. Two doctors were in

attendance, and she was afterwards taken to

hospital, and died at 5.40 on Sunday evening

last.

About a week after the

occurrence, the Mayoress told him that she was

coming into town in a tramcar with her sister

and sister-in-law. She sat in the corner of the

tram behind the driver. When they reached a

certain point the light suddenly went out, and

she felt she was hit. She got up, and found it

difficult to breathe. She thought there were

flames of gas in the tram. She managed to get

out, and made her way to the footpath, where she

was rejoined by her sister and sister-in-law.

The Mayoress told him she was sitting in the

tram when she was hit, and was not getting out.

A sister-in-law said that on the journey they

heard several violent explosions.

Medical evidence showed

that the Mayoress was found to be suffering from

severe wounds to the chest and abdomen. She was

bleeding freely, and after the haemorrhage had

been stopped she was taken to the hospital.

There was a lacerated wound on the left breast,

three inches long and 1½ inches in diameter,

another wound on the left side which had torn

away a portion of the ribs and had opened her

chest and abdomen, and there was another wound

lower down which had penetrated the bone.

Such wounds could have been

caused by splinters of bomb, but no portion of a bomb

had been discovered. Death was due to shock and

septicaemia following upon extensive wounds.

The Coroner said the

verdict of the jury would be that the deceased

died from the injuries spoken to, caused by

bombs dropped from mid-air. This was agreed

upon, and the foreman of the jury expressed deep

sympathy with the Mayor and family.

Coroner’s Comments

The Coroner remarked that

words failed one to express one’s abhorrence

that an unprotected woman going about her humane

duties should be cut off by the act of an enemy

– an act unparalleled, even by any story that

had come down from barbarous times. It might be

said of the Mayoress: “This was a women of good

works”, as was said of the Dorcas of old. The

Mayor had the deepest sympathy of all.

The Mayor, who was

accompanied by his soldier son (wounded),

returned thanks, and said how deeply his family

and himself were moved by the extraordinary

sympathy which had come to them from all the

people in the town. They knew his wife was

brought to the hospital, and on behalf of his

children and himself he wished to say how

grateful they felt to all associated with the

hospital for the unwearying devotion they had

shown towards his wife. He (the Mayor) had been

resident of the institution for nearly three

weeks, and he acknowledged the acts of kindness

which had made it easier to go through the time

of trial. The family would always feel with the

utmost gratitude all that had been done for his

wife, and for the family.

Mary Julia Slater. |

|

|

Bradford Place, the site of the

fatal bombing. |

The bomb crater in Bradford

Place. From a cutting from an unknown newspaper.

|

After the bombing, L21 turned round

and headed back to its base at Nordholz in Germany, but

unfortunately that wasn’t the end. A second Zeppelin,

L19 under the command of Odo Loewe had made the same

navigational error as L21, and roughly followed its

flight path. It arrived around four and a half hours

later, reaching Tipton at about 12.30 a.m. The sight of

the still burning fires from the first raid convinced

Loewe that he had reached his target. The brand new

airship had only been flying for two months, and had

fallen behind because of teething problems with the

engines.

Again bombs were dropped, roughly

in the same places as before, but this time there were

no injuries or fatalities, other than to livestock. The

raid only lasted a short while. Bombs were dropped in

Tipton where The Bush Inn in Park Lane was

badly damaged, just after midnight on 1st

February. A bomb, dropped from L19

exploded in the road in front of the building.

The licensee, Thomas Taylor and his family were

cut by flying debris, but had a lucky escape.

The pub was rebuilt after the war and remained

in business until 1995. Bombs were also dropped

at Wednesbury and the Pleck, where a bomb fell on a stable

and killed

a horse, four pigs, and a number of fowl. Next in line

was Birchills where bombs seriously damaged St. Andrew’s

Church and vicarage.

As the airship began its journey

home, three of the engines failed. The airship attempted

to limp home to its base at Tonder in Denmark. As it

slowly crossed the North Sea it was fired on by the

Dutch. Rifle fire punctured some of its gas cells, and

L19 came down in the sea.

At first it looked as though the

sixteen crew members might be saved because the English

fishing trawler ‘King Stephen’ which had set sail from

Grimsby that morning, came across the sinking airship.

At the time the trawler was illegally fishing in

prohibited waters, and the captain, William Martin,

found himself in a dreadful dilemma.

|

|

The sites that were bombed in

Walsall. |

Should he save the

Zeppelin crew and risk falling foul of the law, or carry

on regardless. Illegal fishing was a serious offence,

for which he could be banned from fishing.

He also had

to consider the possibility that the German crew could

overpower him and his men, and take-over the ship.

He decided to ignore the German’s

pleas for help, and continued on his way. He reported

the sighting when the ship reached port, but a

subsequent search by Royal Navy ships found nothing.

The

L19's crew were never seen alive again. In their last

hours the German crew dropped messages in bottles into

the sea, which washed up six months later in Sweden.

|

|

The incident received world-wide

publicity. Captain Martin was praised by many people for

protecting the safety of his crew, but others, including

members of the German press condemned him. The trawler

found itself on the German Naval High Command’s wanted

list, and even featured in German propaganda.

After the

ship’s return to Grimsby it was taken over by the Royal

Navy, and used as a Q-ship, under the command of

Lieutenant Tom Phillips. Twelve weeks later the ship was

sunk by a German torpedo boat and the crew became

prisoners-of-war.

Captain Martin died of heart

failure on 24th February 1927. During his last year he

received many letters, some praising his actions, but

also hate mail, and death threats.

The full extent of the damage to

buildings in Bradford Place could only be realised the

following morning. A piece of shrapnel can still be seen

embedded in the wall of the Colliseum Night Club where

there is a blue plaque to commemorate the death of the

Lady Mayoress.

There is also a memorial to her memory in

the form of a tablet in the Council House. Walsall’s

Cenotaph now stands on the spot where the bomb exploded.

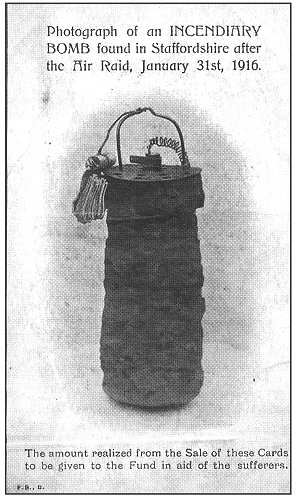

The casing of one of the incendiary bombs is preserved,

and is in the collection at Walsall Museum.

|

|

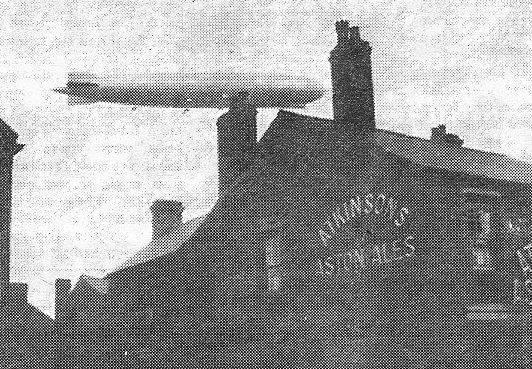

A 1930s Zeppelin, seen over the

Old Barrel pub on Kings Hill, Wednesbury. Courtesy of

David Adams. |

As a result of the raid, street lighting was

turned-off, and people had to shade all domestic

lights. A special steam warning siren was

installed in February, 1916 so that everyone in

the town centre could be warned of any future

air raids. In the event of an air raid, five

long blasts would be given twice. |

|

Factories were asked to arrange for a watchman to

be on duty throughout the night to listen for the siren.

He should then arrange for any furnaces to be damped

down. Factories were also asked not to use hooters of

buzzers between 3 p.m. and 5 a.m. If the siren sounded,

people were to turn any lights out, and anyone in the

street should take cover.

In July 1939, an unexploded bomb,

described as an "Aerial Torpedo" was discovered during

renovation work on a bridge near Kidderminster. It was

reported in an article in ‘The Times’ newspaper on 1st

August, 1939, and believed to have been dropped by L19.

|

|

| From the Express & Star,

Wednesday 2nd February, 1916:

AIR RAID DEATH ROLL

54 KILLED AND 67 INJURED BY

ZEPPELIN BOMBS

LARGEST AREA YET COVERED BY ENEMY

ATTACKS

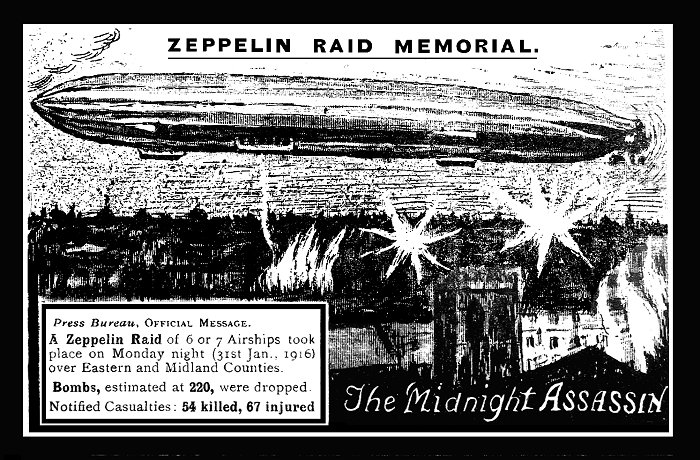

Press Bureau, 6 p.m.

Tuesday night. The War Office issues the

following publication:

The air raid of last night

was attempted on an extensive scale, but it

appears that the raiders were hampered by thick

mist. After crossing the coast the Zeppelins

steered various courses, and dropped bombs at

several towns, and in rural districts, in:

Derbyshire, Leicestershire,

Lincolnshire, Staffordshire.

Some damage to property was

caused. No accurate reports were received until

a very late hour. The casualties notified up to

the time of issuing this statement amount to:

Killed

--------------------- 54

Injured

-------------------- 67

Further reports of Monday

night’s air raid show that the enemy’s air

attack covered a larger area than on any

previous occasion. Bombs were dropped in:

Derbyshire, Leicestershire,

Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk,

Staffordshire.

The number of bombs being

estimated at 220. Except in one part of

Staffordshire the material damage was not

considerable, and in no case was any military

damage caused.

No further casualties have

been reported, and the figures remain as 54

killed, 67 injured. |

|

|

A final view of a Zeppelin. From

the Illustrated War News, 12th April, 1915. |

From an old postcard.

The memorial to Benjamin Goldie in Tipton

Cemetery.

The plaque in Tipton Cemetery.

Derek Nicholls talking about the plaque on

the 31st January, 2026.

|

The memorial in Wood Green

Cemetery, Wednesbury, to those who lost their lives. |

|

The plaque on the other

memorial in Wood Green Cemetery. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|