|

The arrival of steam-powered machinery

greatly increased production in Victorian factories, and led

to the development of much larger and more powerful

machines. Some of the steam engines were massive, such as

the blowing and hoist operating engines used in ironworks to

provide the air blast for blast furnaces, and to power the

hoist used to raise the barrows of burden to the top of the

furnace. Sometimes engines of this type could develop 150hp.

and so large boilers were often used.

In the middle of the nineteenth

century, boilers were made from sections of rolled boiler

plate, joined by simple overlapping joints, some running

around the boiler and others along the length of the boiler.

The joints and the double thickness overlaps were stronger

and less flexible than the surrounding metal, which could

lead to internal cracks or deep pitting caused by variations

in the boiler pressure. The internal cracks could corrode,

further reducing the strength of the boiler.

Such boilers needed regular inspection

and maintenance, and constant monitoring when in use.

Something that was often not fully understood by factory

owners, and their employees. Correctly operating safety

valves were essential. Sometimes operators would screw the

safety valves down to prevent them operating properly, and

so increase boiler pressure to get more work out of their

machines. Often the dangers of high pressure steam were not

fully appreciated. The effects of a boiler explosion could

be catastrophic.

Boiler explosions were not infrequent

in the latter half of the nineteenth century, but the risks

continued to be largely ignored. The sudden failure of a

boiler could result in the total destruction of nearby

buildings, with large pieces of iron being blasted through

the air, often travelling considerable distances. Buildings

some distance away could be damaged, and windows shattered.

People were often killed, scalded, or badly injured, which

had a large impact on the local community.

Wolverhampton suffered from the

terrible affects of several such explosions, which were

often described in graphic detail in the newspapers and

magazines of the day. One of Wolverhampton’s prominent

citizens, who suffered from the after effects of a boiler

explosion that shortened his life, was local industrialist

George Benjamin Thorneycroft who owned Shrubbery Ironworks,

and a number of coal mines, including several in Willenhall.

|

|

George Benjamin Thorneycroft. |

In December 1845 a new pumping engine

was being installed in one of them, and George was there to

oversee the operation. Unfortunately the safety valve was

faulty, and the boiler exploded, killing one man, and

seriously injuring sixteen others, including George. On

regaining consciousness his first words were “Praise the

Lord O my soul.” Followed by “Who else was hurt?”

One year later, with his doctor, Mr. E.

Coleman, he presented himself before lecturing staff and

students at Queen’s College, Birmingham to demonstrate how

the severe burns covering much of his body, had been healed

by the use of cotton wool freely applied to the dressings.

Unfortunately he never fully recovered

from the effects of the explosion. As time progressed he

grew weaker, eventually becoming bedridden. |

| In the early part of 1851 he suffered from brain

disease, and appeared to improve, but a relapse took place,

and he died on 28th April, 1851, at the age of 60. His

funeral procession was viewed by around 20,000 people who

came to pay their last respects. George,

who had been the town’s first mayor after its incorporation

in 1848, was a wealthy and generous man who eagerly

contributed to many organisations and charities. He was a

benefactor to the South Staffordshire General Hospital, and

a Justice of the Peace for Staffordshire and Shropshire.

Another

disastrous explosion

Six years after George’s death, a

terrible explosion occurred in Walsall Street, not that far

from Shrubbery Ironworks, at Benjamin Mason’s factory where

fire irons were made. Benjamin Mason himself had retired,

and the business was being run by his son, Benjamin Mason

junior. The explosion took place at around twenty to four,

on the afternoon of Friday 24th

April, 1857, and had terrible consequences. The

ground shook, and people within a half-mile radius of

Walsall Street thought that an earthquake had shaken the

area. A dense cloud of black dust rose above the factory and

pieces of iron, timber, bricks, building rubble, a human

body, and body parts flew through the air, damaging the

roofs of buildings for a considerable distance, and

shattering the east window of St. George's Church. |

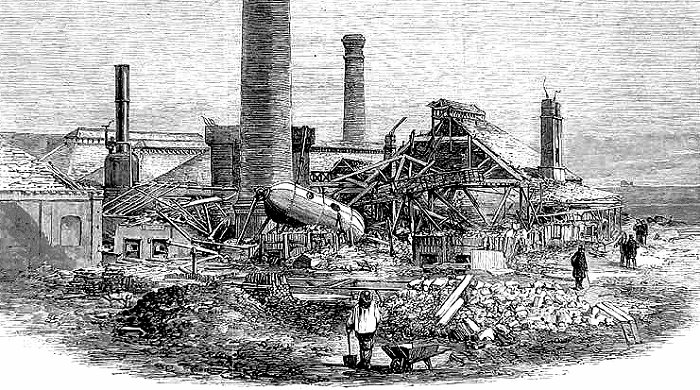

The aftermath of the explosion. From the

Illustrated London News, 2nd May, 1857.

The photograph on which the above

illustration was based. It must be one of the earliest

industrial photos taken in the area. Courtesy of David

Clare. |

|

Most of the factory and some of the

tightly-packed surrounding buildings had been completely

destroyed and converted into rubble. Next to the factory

stood Benjamin Mason’s three storey malthouse, which became

a pile of rubble, even though its walls were thirteen inches

thick. The egg-shaped, vertical boiler had been mounted

against the malthouse wall. It powered a small engine used

for the fire-iron factory, and also for a grindery, and

wood-turning establishment at the rear of the factory. At

the time of the explosion most of the employees in the

establishments had been at work. All that survived in the

factory was the tall substantial chimney, to which the

boiler had been fixed. The chimney completely shielded one

of the employees who was behind it in the malthouse at the

time of the explosion, saving his life. The grindery and the

wood turning establishment had their roofs blown-off, and

were badly damaged.

A piece of the boiler weighing 2

hundredweights had been hurled about a hundred yards. At the

time of the explosion, Benjamin Mason junior, and the

engineman, Joe Cornfield had just screwed the safety valve

down because the boiler feeding pipe had burst, and the

nearly empty boiler was red hot. They attempted to cool the

boiler by adding cold water, which quickly boiled and

produced a lot of steam. The boiler instantly exploded,

killing both of them. Joe was thrown through the air and

crashed through the roof of a nearby house. His clothes had

been torn-off, leaving him naked and bleeding. Many of his

bones were broken, and he was badly scalded. He died a few

minutes later. Benjamin’s fate was even more gruesome. His

body, minus arms, and the top of his head was found amongst

the ruins. One arm was found in Bilston Street near the

cattle market.

Another employee, Tom Nightingale, who

alerted Mason and Cornfield to the damaged feed pipe, and

was with them at the time of the explosion, escaped without

injury. Several others were not so lucky. Another colleague,

Tom Holdridge received terrible injuries and died that night

in the South Staffordshire General Hospital and Dispensary,

in Cleveland Road. Two children, Matthew William Turner aged

5, who had been playing in the street, and Isabella Hall

aged 12 were also killed, both by falling debris. Isabella

had been on an errand to buy a writing book for her father,

who rushed to the scene of the explosion. He saw a policeman

carrying a body away from the scene and recognised her

frock. It must have been a terrible moment for him.

Another person was seriously injured,

and nine others received lesser injuries. A memorial service

was held on the following Sunday in front of the cattle

market, and an inquest took place at the Blue Ball Inn in

Bilston Street. At the inquest it was stated that the boiler

had been purchased second-hand, and installed six years

earlier. It had previously been enlarged, and repaired

several times. It was also stated that the water in the

boiler had been allowed to go so low that the metal was

red-hot. The explosion occurred when cold water was

poured-in.

The inquest came to the conclusion that

the deceased persons died as a result of their injuries

received by the explosion of the boiler, and that the

explosion was caused by the gross negligence of Benjamin

Mason junior.

The

explosion at Millfields Iron Works

Five years later another catastrophic

boiler explosion occurred about a mile and a half away from

Walsall Street, at Millfields Iron Works. The explosion took

place on Tuesday 15th April, 1862, at about 11.15 a.m.

The factory, previously owned by the

Birmingham Banking Company, was eleven years old. It closed

in 1858, and had been idle for four years. There had been a

previous accident on the site, which caused the death of

five workers on 5th May, 1857.

In early 1862 the factory was purchased

by Thomas Rose, who had been looking for sometime for a

suitably-equipped iron works. Having found what he wanted,

he employed around 40 men and started production, in the

hope that he would make his fortune thanks to the insatiable

demand for iron at the time.

The factory consisted of two forges and

three mills. At the time only one forge was in operation. It

consisted of twenty puddling furnaces, a shingling hammer, a

rolling mill, and an 80 hp. steam engine that worked the

massive shingling hammer. Steam for the engine was provided

by two cylindrical boilers with hemispheric ends, both about

twenty feet long, and nine feet in diameter. The boilers

were heated by the hot gases from the flues of some of the

puddling furnaces. One boiler was heated by four flues, the

other by two. They were made by John Elwell & Company, at

Priestfields.

When the explosion occurred, the puddlers from the four furnaces attached to boiler number

one, were taking their red-hot balls of puddled iron to the

shingling hammer to produce puddled bars, which were cut-up,

reheated, and rolled into merchantable iron in the rolling

mill. About forty people were at work at the time. |

The scene of the boiler explosion at

Millfields Ironworks. From the Illustrated London News 26th April,

1862.

|

Everything seemed to be going well,

until without warning, an excruciatingly loud noise, like a

clap of thunder, shook the building. The roof blew off, the

walls collapsed, and the building was totally destroyed.

Boiler number one had exploded and been torn apart. Three

quarters of it, weighing around eight tons was tossed 200 or

300 feet into the air and landed on the other side of the

railway line, over three hundred yards away. The other

quarter, torn into three parts, had been blown through the

forge, each part travelling in a different direction,

tearing down the roof supporting pillars, and ripping the

massive roof timbers apart. The furnaces were also torn

apart, sending their contents, consisting of the molten

metal and the burning fires, throughout the factory, to

complete the appalling catastrophe.

There were bodies and seriously injured

people everywhere. Some were buried beneath the molten iron,

or beneath fragments of the fires, or red-hot brickwork.

Some people were badly injured by the falling fragments,

many of which fell on the boats on the adjacent canal.

Within an hour fourteen bodies had been recovered, all of

them shockingly mutilated. One person lost his head, which

was never recovered, and another had been cut in two. The

bodies were so badly damaged that few could be positively

identified, something that was not helped by the fact that

some of the workers had only been taken-on that morning.

Fifteen of the injured were taken to

the South Staffordshire General Hospital, and six to their

homes. Three died on the way to hospital, and another died

whilst on his way home.

The damage to the works was estimated

at between £2,000 and £3,000. The area around where the

boiler stood was showered with scalding hot water from the

boiler, which indicated that the boiler was full at the time

of the explosion. Below the water line was a seam, and a row

of rivets with the heads burnt off, which suggested that the

explosion was caused by poor quality joints in the boiler

barrel. The night before the explosion, the engineer on duty

had noticed a loose rivet, which should have started alarm

bells ringing.

The explosion, which had been heard for

miles around, demolished everything within a hundred yards

of the factory. One lucky survivor, 12 years old Billy

Williams, was on his second day at work, and standing near

to the boiler when it exploded. He was blown more than 200

yards, and ended-up with little more than a few bruises.

The rescuers who quickly attended the

scene, were faced with a huge pile of twisted metal, broken

smouldering masonry, and the desperate cries of injured and

dying men. Throughout the day they searched for bodies,

often only finding limbs, or a head. Three victims who were

killed by falling debris were on a canal boat over a hundred

yards away. Twenty men died at the scene, and another eight

from their injuries.

It was discovered that the boiler had

not been properly inspected or maintained. It had not even

been inspected since Thomas Rose reopened the factory, even

though it had been idle for four years. Yet again the

factory owner and his employees had failed to appreciate the

dangers of high pressure steam.

There were other boiler explosions in

the area. One on 5th November, 1884 at Spring Vale killed

three workmen, and a second at Tupper & Company’s ironworks

at Bradley on 20th January, 1903 killed four workmen and

injured another eleven. It took a long time before boilers

were treated with the respect they deserve, and were

properly maintained, and monitored. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|