|

|

|

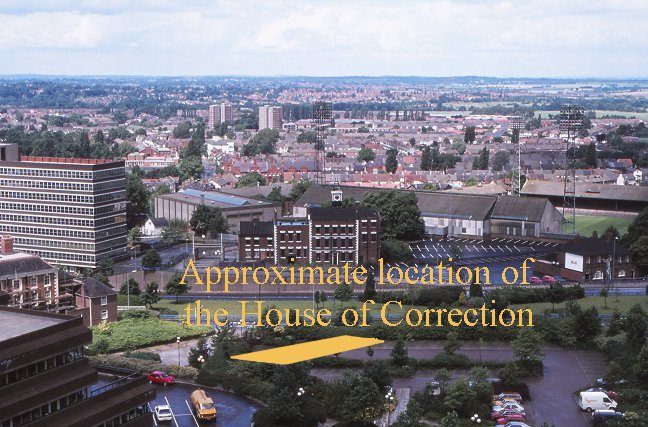

North Street, one of Wolverhampton’s oldest

streets, was once the site of the local jail, known as the House of

Correction, which opened in 1745. It was a county gaol, and stood on

the eastern side of North Street, opposite Giffard House, where St.

Peter’s Car Park now stands. County gaols first appeared at the end

of the

17th century as a result of the Gaol Act of 1698 which gave Justices

of the Peace the responsibility building and maintaining them. They

were seen as a better alternative to private lockups. Before the

opening of the House of Correction, convicted prisoners in

Wolverhampton were sent to the county jail at Stafford, which at the

time was either in the vicinity of the now-demolished North Gate, or

in North Gate itself. Stafford Jail was built on its present site in

1793. After the opening of the House of Correction, criminals could

be sent there, or to the county jail.

People sent to trial were dealt with by three

courts, the Assizes, the Quarter Sessions, and the Petty Sessions.

The assizes met twice a year and dealt with more serious offences,

including some civil actions. The quarter sessions court, under the

control of at least two Justices of the Peace was held four times a

year, early January (Epiphany), Easter or Lent, Midsummer, and

Michaelmas. It dealt with criminal and administrative matters. The

third court, the petty sessions, the lowest tier in the court

system, appeared at the beginning of the 18th century to relieve the

quarter sessions of some of the less important cases. Cases included

theft, larceny, poor law disputes, assaults, drunkenness, and

arbitration. Some of the cases were passed-on to the Quarter

Sessions.

|

The view from St. Peter's Church tower in

1988.

|

In the 18th century, punishment for even

relatively minor crimes could be severe. Convicted people could be

whipped, publically or privately, or incarcerated in the stocks.

Prison sentences were much longer than we are used to today. People

who were in debt often ended-up in prison, as did vagrants. Debtors

formed a large percentage of the prison population, often being

innocent trades’ people who had fallen on hard times. They were kept

there until they paid their debts, by legal action taken against

them by their creditors, and were committed under an act for the

recovery of small debts for Wolverhampton and the neighbourhood.

Wolverhampton’s House of Correction was

financed by Staffordshire County Council from the county rates, and

administered by the Under Sheriff of the county, and the

magistrates. People sentenced to short terms of imprisonment there

were often convicted at the Petty Sessions. The famous prison

reformer John Howard visited the House of Correction in 1779 and

1782. He considered the conditions in the prison to be appalling.

The insecure building was in a bad state of repair, and prisoners

were kept in irons for the slightest offence. An article appeared in

the Wolverhampton Chronicle in September 1789 about the insecure

prison. A number of prisoners had sawn-off their irons, and made a

large hole in the wall, through which to escape. Luckily they were

apprehended by the keeper before they got away.

Between 1798 and 1800 the prison was rebuilt at

a cost of £803, and afterwards referred to as the Crib, or

Bridewell. The building had accommodation for male and female

prisoners. The rooms on the ground floor included a day room with a

fireplace, a work room, and two solitary cells. On the first floor

were ten sleeping cells and an infirmary room with a wooden bed and

a fireplace. The cells measured 8 feet by 6 feet, and beds consisted of a rush

mattress, two blankets and a coverlet. There were two flagged

courtyards, one for the men measuring about 33 feet by 18 feet, with

a pump and a crude open air toilet, and another for the women, measuring about 27 feet

by 10 feet, with a water supply and a crude open air toilet. The

courtyards were accessed from the cells by a passage, 4 feet 5

inches wide.

In 1801 George Roberts was appointed Keeper of

the Bridewell, at an annual salary of £80. He became infamous in the

town after attempting to get two innocent men convicted of highway

robbery. The offence was punishable by hanging. The two men were

duly convicted and sentenced to hang outside Stafford jail on the

morning of Saturday 16th August, 1817. Roberts was entitled to a

considerable reward, but luckily the men were pardoned, mainly due

to the efforts of Charles Mander. Although Roberts was suspected of

falsifying evidence, he remained as keeper at the North Street

Bridewell until its closure in 1821.

Prisoners were employed in making nails,

screws, and sacks. In 1818 a prisoner could earn £6.15s.0d. a year

for labour, but would only receive one sixth of the amount, the

remainder was divided equally between the county council and the

keeper. At the time the weekly allowance consisted of 6½ lbs of

bread, 1 lb of cheese and 10 lbs of potatoes, as well as a few

clothes, but only when necessary for health and cleanliness.

Although the prison had been rebuilt,

conditions were still poor, and soon began to deteriorate.

Overcrowding was often a problem. In July 1812 forty seven prisoners

were held there, and in June 1817 there were sixty five prisoners.

In March 1820 a highly critical report was submitted to William

Dyott, Chairman of the Staffordshire County Gaol Committee. The

report stated that 39 prisoners were crammed into filthy and poorly

ventilated cells, and many prisoners were interned in the prison

yard. The cell for vagrants was 'in the very worst state of filth',

and in another cell there were eight women and their nine

illegitimate children, living in disgusting squalor. All the

prisoners were in an exceedingly dirty state, and none was at work,

although the keeper stated that he occasionally employed male

prisoners to polish tea trays. |

|

A handbill from 1820. |

The report concluded that “this prison appears

a receptacle for every species of delinquency, from the murderer to

the idle apprentice boy, all crowded in one common yard without

employment, though mostly committed to be kept to hard labour”. Partly as a result of these revelations, the

Staffordshire authorities decided to close the prison in 1821. It

was auctioned at the Red Lion Inn in December 1824, and described as

“a good substantial house, with two parlours, two kitchens, pantry,

two cellars, and a small garden.

The prison side comprises of eight

different spaces or open yards, with a pump of excellent water,

eight wards and three shops on the ground floor, and on the upper

storey seventeen distinct rooms or night cells, secured with an

immense quantity of iron gates, grates, etc. and lined with capital

oak timber. It is encompassed with very strong and lofty walls, in

which are several hundred thousand bricks.” |

|

Before closure, alternative premises

were

found in Stafford Street, roughly where the drill hall used to be.

The building on the site today, which is opposite the university, is

used for student accommodation. The new Bridewell was little better

than the old, and often suffered from overcrowding. An article in

the Wolverhampton Chronicle in November 1837 described how a woman,

who had been detained on a minor charge, had to be secured in a room

with barred windows in the home of parish constable, John Fenn. Her

escape from the room highlighted the necessity for a proper place of

confinement in the town. By 1841 conditions in the prison were so bad

that on the 10th February, the Chronicle included an article urging

the construction of a new prison, which was badly needed. It

described the prison as follows:

“Let anyone visit our Crib …. and we feel

confident that every feeling of humanity will revolt at confining a

fellow creature in such a pestiferous spot - in summer, steaming

with the most unwholesome effluvia, and in winter exposing its

unhappy inmates to the most pinching cold.”

|

Stafford Street in 2001. The Bridewell was

roughly in the centre of the photo.

|

Although the terrible situation was discussed

by the Improvement Commissioners, nothing was done. Luckily the

matter did not rest there. Wolverhampton’s Magistrates began to

urge the county authorities to build a new police station and jail

in the town. In September 1844, Henry Hill, J.P. stated that the

cells in the Bridewell could only hold 25 to 30 prisoners in

terrible conditions. The appalling state of affairs was also

described by other magistrates, and plans were drawn-up for a new

police station with living quarters for policemen, and cells for

prisoners.

In March 1845, land in Garrick Street was

purchased from the Duke of Cleveland, and work on the new police

station soon got underway. It was completed in 1846 at a cost of

£3,700, paid by the county rates. It consisted of a courtroom, a

house for the Chief Constable, accommodation for policemen, and 8

cells with room for 40 prisoners. Finally the town’s Bridewell could

be closed, bringing to end an awful chapter in the life of local

prisoners. In 1849, the Wolverhampton Borough Police Force was

established, with headquarters at Garrick Street Police Station.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|