|

Background

By the mid nineteen thirties

Wolverhampton desperately needed a suitable music venue with

good acoustics and comfortable seating for large audiences.

At the time there were three buildings in the town where

concerts could be held; the Agricultural Hall, the Baths

Assembly Hall, and the Drill Hall, none of which was built

with concerts in mind. They all suffered from terrible

acoustics as can be seen from the following contemporary

descriptions:

Sir Henry Wood said that to give a

concert in the Agricultural Hall was “like performing in

a railway station.”

Mr. A. J. Sheldon, music critic

of the Birmingham Post described the Drill Hall as “Wolverhampton’s

sorry substitute for a concert building. He also stated that

“Its acoustics are not only bad, they are inconsistent. A

little way past the centre of the floor the orchestra and

chorus sound as if a gentle dispute were in progress a few

miles off. To one seated on the tavern-like benches at the

rear of the place, the volume of sound, though fuller, is

completely distorted. If Mr. Joseph Lewis, who conducted

last night, has any regard for his personal reputation. He

will not again seek any critical appreciation of such a work

when its performance is possible only under such wretched

conditions.”

He summarised his feelings for the

building as follows:

“Wolverhampton may possess a capable

fire brigade, yet if ever the Drill Hall of the town should

become ablaze the imagination can visualise the musical

enthusiasts of the city making a united stand against the

passage of anybody attempting to save the building.”

“The Wolverhampton Drill Hall would

serve admirably the purpose for which it was designed; as a

concert room however, it is an atrocity. It is even chillier

to begin with, than the Birmingham Town Hall has been since

it was reopened to the public. An additional diversion is a

still chillier draught which blows down the centre of the

room while a concert is in progress. Doors are banged

unmercifully while the music is going on, and when a

particularly soft bit of playing is entered on, noises come

from the back of the hall which suggest a well patronised

canteen not far away.” |

|

The public baths. |

The Baths Assembly Hall in the boarded-over swimming

pool was similarly draughty. As well as bad acoustics it had

a bare and naturally bath-like appearance, with a canopy of

iron girders. The lack of a suitable venue for concerts

was a serious problem for local orchestral and operatic

societies. Many of them ceased to exist because of the lack

of a suitable place to perform. One of the casualties was

the Wolverhampton Musical Society.

The reasons for its demise were listed in an article in

the Express & Star by Mr. E. M. Purkis entitled “An Inquest

on Wolverhampton Music.” |

|

An Inquest on Wolverhampton

Music

What are the reasons which have brought

this splendid society to an end? Broadcasting is blamed for

affecting the attendances, but many of those who have

followed the society's career are satisfied that the lack of

a suitable concert hall is what has actually killed it.

Every time the Musical Society gave a concert in the Drill

Hall it cost them nearly £40 as a minimum, and up to £60 in

the early years, for the hire of the hall, hire of chairs,

erection and taking down of platform, extra light and

cleaning….. Roughly the Musical Society have dropped in

their career not less than £650 through the lack of a public

hall. Their deficit when they reached their financial crisis

early last year was about half that, which seems to show

that the hall difficulty has meant the difference between a

handsome balance in hand and a crushing deficit. The lack of

a hall has also been a severe handicap in other ways.

The Drill Hall serves excellently the

purpose for which it was built, but it was never built for a

concert hall. It is cold and draughty. There are no

cloakroom facilities.

The concert patron had to listen seated

upon a small uncomfortable chair, usually hedged-in like the

proverbial sardine, and with coats, hats and umbrellas

packed all around him. Little wonder if many preferred to

listen to broadcast music in the comfort of their own homes.

There is no doubt whatever that the uncomfortable conditions

kept many people away and had their part in gradually

reducing the audiences.

The same drawbacks were felt to

some extent at the Baths Assembly Room, which,

however, is not really large enough for concerts run

on the scale of the Musical Society. Other reasons

have no doubt operated against Wolverhampton Choral

Society, which has also suspended operations, but a

good hall would have given them, too, a better

chance, and any organisation which seeks to provide

concerts on a large scale in Wolverhampton comes up

against the same difficulty.

As most people are aware, the

Wolverhampton Corporation have a site for a public

hall adjoining the Town Hall. Upon it stands the

telephone exchange, and until that is replaced by a

new exchange elsewhere which the postal authorities

have in view, that site will not be available. Plans

for the new exchange are at the moment passing

through the necessary channels for adoption, a slow

process with government departments. The contracted

date for giving-up the site for the Corporation is

May, 1932. Add two years to that for the erection of

a public hall and we have about five years to wait

before we can have any hope of the hall being ready

for use. The final moral of the Musical Society's

decision to close down, however, is most certainly

that Wolverhampton cannot hope to stage big concerts

again without great trouble and anxiety, if at all,

until it has secured that public hall which will

mean so much to its culture and social well-being.

|

|

|

Planning

a new public hall

For many years people talked about the

possibility of building a civic hall, but nothing happened

until 1920 when Councillor Clement Jenks raised the matter

at a council meeting. It took another two years for the

council to seriously consider the project.

In August 1922 the General Purposes

Committee was asked to recommend seven of its members to

form a Civic Hall Committee to consider, and report on the

desirability of building a hall out of the rates, and if so,

what form it should take, and where it would be built.

Word of the formation of the committee soon got around and

great public interest was shown in the project. It was aided

by the Express & Star which published articles and letters

about the project, and also ran a competition to decide on

the most desirable facilities that a public hall should

have.

The competition was won by two people who shared the

prize. Thanks to the newspaper’s influence, most of their

suggestions were eventually incorporated into the new

building. The competition and the articles in the newspaper

greatly increased public interest in the project, and

stirred the council into action. |

Councillor Bertram Kidson, J.P.

Chairman of the Civic Hall Committee. |

| In July 1924 the council decided to adopt the

committee’s recommendations after a debate that lasted three

hours, and a vote which was won by 19 to 16 votes. It was

estimated that the hall would cost around £80,000 which

equated to a two penny rate. On the following day the

Express & Star wrote: |

| The civic life of the town will unquestionably

be enhanced when a suitable hall has been completed.

Those who today are possibly feeling somewhat timid

will, we are sure, eventually realise the necessity

for a forward step and the wisdom of the decision,

though this was reached by a small majority of the

council. |

|

|

Although it seemed that the project

would soon get underway, there were still many delays which

lasted over ten years. In August 1925 the council launched

an improvement scheme to clear a site in readiness for the

building of the hall, but little else happened until

February 1934 when the Civic Hall Committee asked the

council to proceed as soon as possible with the scheme, and

organise an open architectural competition for the design.

The council agreed to the

recommendation, and two months later the committee produced

a second report which suggested that the hall should be used

for banquets, concerts, dances, meetings, and receptions. It

should cost no more than £100,000 plus an allowance of

£10,000 for contingencies, and fluctuations in the price of

materials and labour. Prizes of £350, £250, and £150 were

offered for designs.

There were still further difficulties.

By 1935 the estimated cost of the hall had increased to

£150,000. The council made an application to borrow the

money which was considered at an inquiry run by the Ministry

of Health. The Wolverhampton Property Owners’ Defence League

opposed the plan, and suggested that it should be postponed

for five years, but the Minister approved the plan and

building work began in April 1936. |

|

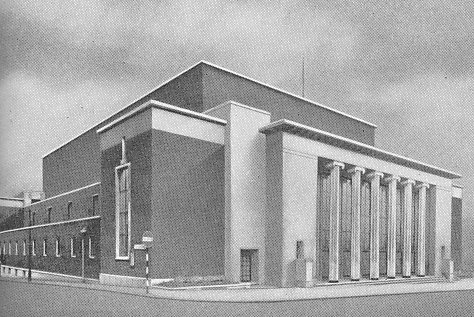

The proposed Civic Hall. |

The competition for the design was won by E. D. Lyons

and L. Isreal, A.A.R.I.B.A. of Ilford in Essex.

There were 122 entries from all parts of the country

which were examined by the eminent architect Mr. Cowles

Voysey who said of the winning design:

“It is an excellent scheme which I feel sure will

produce a very satisfactory building.” |

|

The new

Hall

As building work progressed, it was

supervised by the Civic Hall Committee, which in 1938 had the following

members:

| Councillor Bertram Kidson,

J.P. Chairman |

Councillor R. E. Probert.

Mayor of Wolverhampton |

| Alderman Sir Charles A.

Mander, Bt., D.L., J.P. Deputy

Mayor |

| Alderman M. Christopher,

J.P. |

Alderman W. Rooker |

| Alderman J. Clark, J.P. |

Alderman J. Whittaker, J.P. |

| Alderman M. H. Costley |

Councillor H. Bowdler |

| Alderman A. Davies, J.P. |

Councillor G. Luce |

| Alderman T. Frost, J.P. |

Councillor T. W. Simpson |

| Alderman J. Haddock |

Councillor F. W. Smithies |

| Alderman J. F. Myatt, J.P. |

|

Councillor Bertram Kidson, a chartered

accountant, and mayor of Wolverhampton in

1933/34 had been chairman since the

committee was formed. |

|

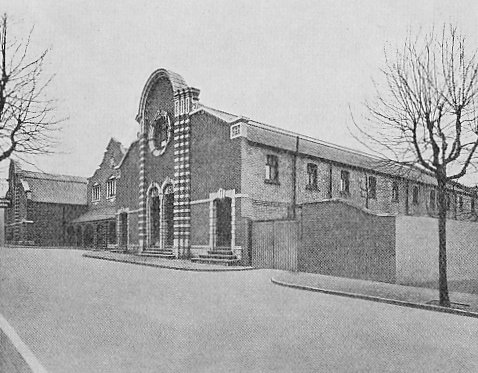

| The building, built of local multi-coloured

brick with Portland stone dressings, took around two

years to complete. It was built by a local firm,

Henry Willcock & Company Limited.

An early view of the

building. |

|

|

The

contractors were as follows: |

| Henry Willcock & Company

Limited. Builders |

Rubery Owen & Company Ltd.

Structural steelwork |

| Henry Vale & Sons. Quantity

surveyors |

S. H. White & Son.

Consulting structural engineers |

| G. Stinton Jones and

Partners. Consulting engineers |

J. Gilbert Mills. Organ

consultant |

| J. R. Newton. Clerk of works |

Shaw’s Glazed Brick Co. Ltd.

External glazed ceramics |

| Troughton &

Young Limited. Electrical work |

Manley &

Regulus Ltd. Mechanical services, heating

and ventilation |

| W. Wadsworth Limited. Lifts |

Waygood-Otis Limited.

Hand-power lifts |

| Horseley Smith

& Company Limited. Dance floor |

James Gibbons

Limited. Metal windows, doors, and

ironmongery |

| Baldwins (Birmingham)

Limited. Sanitary fittings |

Potter Rax Limited.

Shutters |

| Gimson & Company (Leicester)

Limited. Stage equipment |

Haywards Limited. Saucer

lights in the cloakrooms |

| Tentest Fibre Board Company

Limited. Wall boarding |

Henry Miller Limited. Chair

lifts |

| Carron Company Ltd.

Staircases and kitchen equipment |

Art Pavements Limited.

Terrazzo floors |

| Fenning &

Company Limited. Marble panelling |

H. H. Martyn &

Company Ltd. Handrails, balustrading,

grilles, etc. |

| Starkie Gardner

& Company Ltd. Screens and cloakroom

fittings |

James Walker

Limited. Fibrous plaster |

| Furse & Company

Limited. Curtain tracks, steel shutters,

projection room etc. |

Carter &

Company. Decorative tiling |

| Charles Hunter. Dunlop

rubber flooring |

Eric Munday. Lettering,

motifs, etc. |

| G. H. Turner & Company.

Light fittings |

John Compton Organ Company.

Organ |

| James Clark & Sons. Mirrors |

Stourbridge Glazed Brick

Company Limited. Wall tiling |

| W. Beddows &

Company Limited. Flush doors |

Rivers-Moore

Radio Limited. Public address equipment and

deaf aid system |

| PEL Limited.

Chairs |

Kinematograph

Equipment Company Ltd. Projection room

equipment, carpets and stage equipment |

| Braby & Company. Ventilators |

Heal & Son Limited.

Furniture |

| Marion Dorn Limited and

Peter Jones. Curtains |

Kingfisher Limited. Chairs

for the orchestra |

| John Lewis & Company

Limited. Linoleum |

W. Smith & Company Limited.

Carpet druggets |

| J. Avery & Company. Blinds |

|

|

|

| A description of the

building in its original form |

|

The Civic Hall. |

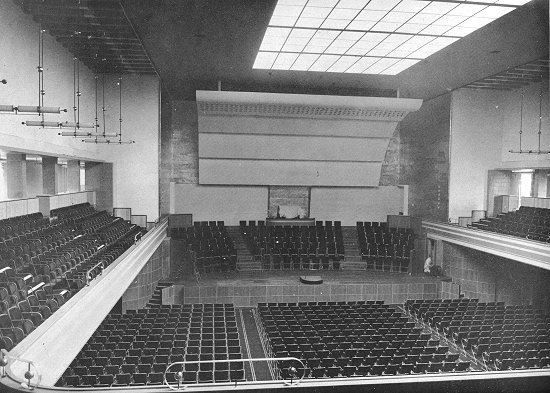

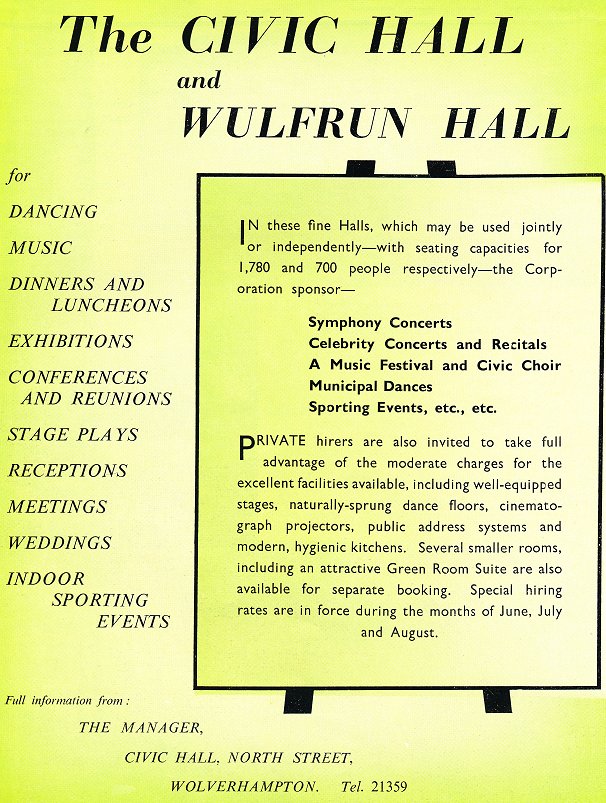

There are two main assembly halls, the

larger Civic Hall and the smaller Wulfrun Hall, each forming

an independent unit with separate entrances and cloakrooms,

but for important functions they can be used as a suite of

rooms with a centrally-placed refreshment room and crush

room.

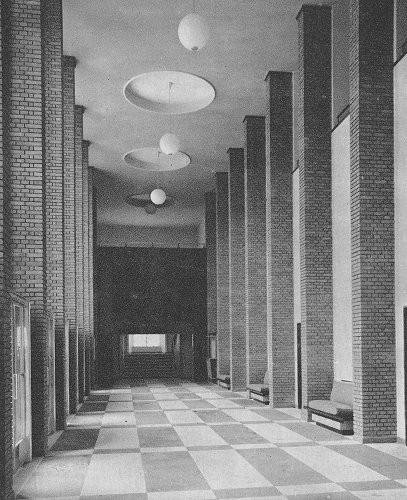

The entrance leads into a large

vestibule extending across the full width of the building,

with an open gallery on three sides, and large doors leading

into the Civic hall.

|

| The hall seats 1,283 people on the ground floor, and 497

in the gallery. A lower platform has space for an 80 piece

orchestra, with tiers behind, for a choir of up to 200.

The hall is completely encircled by promenades at both

ground and balcony levels. The colour scheme is grey,

primrose and fawn, with striped decorations, and oyster

coloured glass in the ceiling through which light filters.

The platform is flanked by silvered walls, and the

upholstery and carpets are a rich dark brown. |

The Civic Hall during a rehearsal by

the Hallé Orchestra. |

|

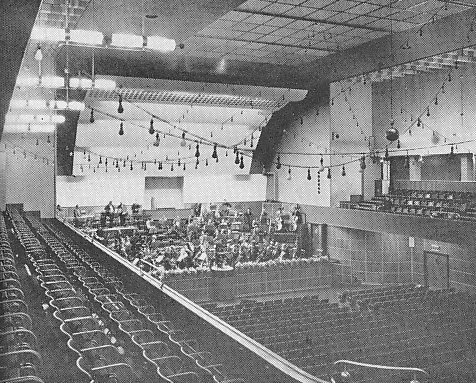

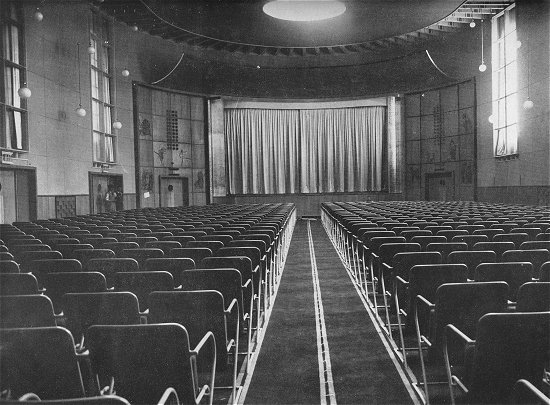

The Wulfrun Hall. |

The Compton organ has over 5,500 pipes,

and an electronic unit which provides many solo tones, and

carillon and bell effects.

The console has four manuals, sixty one

notes, and a concave pedal board with thirty two notes.

The Wulfrun Hall has a seating capacity

of 700 with walls covered with acoustic boards, and red

ceiling beams and door panels.

|

| On each side of the proscenium opening are murals

depicting the civic and social life of the town. They were

produced by Muriel Gilbert, a young artist who was

responsible for many of the paintings on the R.M.S. Queen

Mary. Both halls are equipped with cinema projectors,

naturally sprung dance floors, and a public address system.

There is ample accommodation for visiting artists on the

upper floors and under the stage of the Wulfrun Hall.

There is a large, well-equipped kitchen which can supply

anything from light refreshments to a banquet for 500.

There is a fully backed-up air-conditioning plant for

both halls with viscous oil filters to purify, wash, and

heat the air as required.

Great consideration was given to the acoustics in both

halls. One of the leading experts in the field, Mr. Hope

Bagenal, A.R.I.B.A. advised on the installation. |

The murals in the Wulfrun hall. |

| The official opening and

the early years |

|

The Wulfrun Hall, as preparations are

made for a dinner. |

The official opening took place on Thursday 12th May,

1938.

The proceedings began at 11.30 when Mr. G. D. Cunningham

the city organist of Birmingham gave a recital on the

Compton Organ while the audience arrived.

He was the first musician to play in the new building.

At 12.10 the official procession arrived. |

|

The following people took part in the

official procession:

|

| The Chief Constable |

The Mayor, Councillor R. E. Probert |

| The Town Clerk, J.

Brock Allon |

The Chairman of the

Civic Hall Committee, Councillor Bertram Kidson |

| The Earl of Dartmouth |

The Deputy Mayor, Alderman Charles

A. Mander |

| The Mayor’s Chaplain, Canon J.

Brierley |

The High Sheriff, Major S. J.

Thompson |

| The Bishop of Lichfield |

Sir Robert Bird, M.P. |

| Geoffrey le M. Mander, M.P. |

Ian Hannah, M.P. |

| The Borough Coroner, C. O. Langley |

The Stipediary Magistrate, Bertram

Grimley |

| The Lord Mayor of

Birmingham, Councillor E. R. Canning |

The Chairman of

Staffordshire County Council, Alderman R. G.

Patterson |

| The Mayors and Town

Clerks of Walsall, Dudley, West Bromwich, Smethwick,

Stafford, Wednesbury, Bilston, and Rowley Regis |

The Civic Hall

Committee |

| The Architects, E.D. Lyons and L.

Israel |

The Builders, H. B. Wilcock, and F.

Stephens |

|

| The procession proceeded through the hall to the

platform where speeches were given, prayers were said, hymns

were sung, and Lord Dartmouth declared the building open for

public use. This was followed by a short recital given by the

Wolverhampton Musical Society, conducted by Harold Gray and

accompanied by G. D. Cunningham on the organ.

Afterwards the civic party departed and the audience left

the building.

In the evening, a ball attended by all of the civic

dignitaries was held to celebrate the opening.

The guests were entertained by Jack Hylton and his

orchestra. |

|

|

The vestibule. |

The first concert in the hall took

place four days later. It was given by the Old Royals

Association (old pupils of the Royal Wolverhampton School)

and featured Webster Booth and Ann Ziegler as soloists.

The first orchestral concert in the

Civic Hall was appropriately given by the Wolverhampton

Philharmonic, conducted by John Matthews.

They gave three concerts in the hall in

1938 and two in 1939, but sadly to small audiences, which

resulted in the disbanding of the orchestra.

In the 1940s the hall became well known

in the concert world because many of the country’s leading

orchestras played there, mainly to get away from the London

blitz.

As a result, audiences grew larger, and

the venue became greatly appreciated and successful.

|

| Between 1940 and 1945 concerts were given by the London

Philharmonic Orchestra, the Liverpool Philharmonic

Orchestra, the Hallé Orchestra, the London Symphony

Orchestra, the National Symphony Orchestra, the City of

Birmingham Orchestra, the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, and the BBC

Men’s Chorus.

Conductors included Sir Thomas Beecham, Sir Henry Wood,

Sir Adrian Bolt, John Barbirolli, Malcolm Sargent, and

Albert Coates.

There was also a Shakespearean season in the Wulfrun

Hall, given by Donald Wolfit and his company. |

A corner of the balcony. |

|

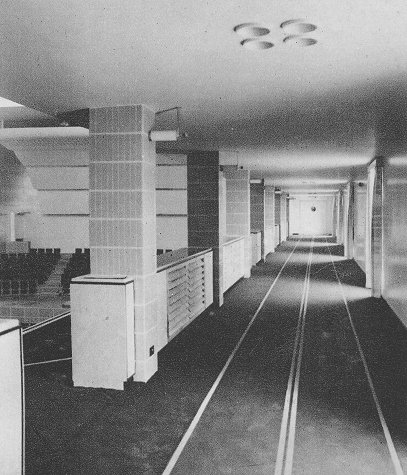

The balcony promenade. |

For a time, concerts were planned by the Music Advisory

Committee, set up by the Civic Hall Committee, and

consisting of local music lovers who made recommendations

about the number of concerts, who should give them, and who

should appear in them.

The committee tried to ensure that concert-goers would

hear as wide a range of the best music and artists as

possible, but their recommendations were not always

followed.

In June 1943 the Civic Hall Committee decided to let

visiting orchestras hire the hall, and take all of the

profits, rather than engaging orchestras.

So there was no further use for the Music Advisory

Committee, which was disbanded. |

| At the time, seat prices varied from six shillings to

two shillings and six pence. Assuming the Civic Hall was

full, the takings amounted to just under four hundred

pounds, which was about the same as the cost of engaging an

orchestra, and paying for advertising etc.

So at the time it was not very profitable. |

The refreshment room which is served

by lifts from the kitchens below. |

|

Another view of the Wulfrun Hall. |

The total takings in the Wulfrun Hall were one hundred

and five pounds, so many concerts ran at a loss.

At the same time the council was still paying off the

debt from the original loan.

Many ratepayers complained, but as the hall became more

successful, and the debt was paid-off, people came to

realise what a wonderful amenity it was. |

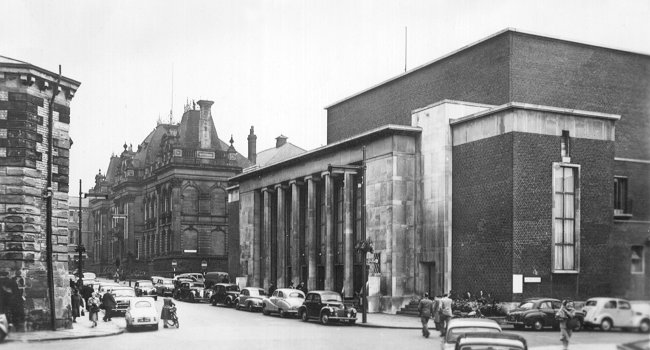

| A later view of the Civic Hall

with Corporation Street on the left. |

|

|

From an old postcard. |

|

Later

Years

In the 1950s and 1960s the halls became

a fashionable place for all kinds of entertainment and are now a

well known and popular venue. All kinds of events featuring

well known artists have been held, including classical music

concerts, opera, popular music, comedy, sporting events

such as boxing and wrestling, and televised darts tournaments.

There are also club nights, ballroom dancing, and the annual

Wolverhampton Beer Festival.

|

A view of the Civic Hall from a 1950s

postcard.

An advert from 1965.

|

An advert from 1968. |

The Cultural and Entertainments

Committee regularly sponsored symphony concerts, plays,

dances, and the civic choir. The committee also organised a

competitive music festival, a festival of contemporary

music, and a drama festival. The Arts Society and a film

society regularly met at the Wulfrun Hall.

By the late 1960s many famous variety

stars had appeared at the Civic Hall including Danny Kaye,

Gracie Fields, Tommy Steele, Diana Dors, Johnny Ray, and Nat

King Cole. Every leading British dance band appeared

there, and many of the events were regularly broadcast on

radio and television.

A few years ago the building was

refurbished to increase the seating capacity to 3,000, and

expand the stage area. Work began on the three million pound

project in April 2000 and included the building of two new

gallery bars with frameless glazed facades, new toilets and

cloakrooms, new fire escapes and dressing rooms, bars on the

ground floor, a gallery promenade to provide easy access to

seating, and improved servicing facilities with direct

access to Corporation Street. The architects were Penoyre &

Prasad, of London.

|

A view from the early 1970s.

|

While the work was underway a new music

venue opened in 2001 in North Street at the Little Civic,

which was previously called the Town Hall Tavern. It opened

to provide a box office facility while the renovation work

was underway, and soon became an extremely popular venue for

lovers of pop music. It closed in 2009, much to the

disappointment of many people, and later reopened as the

Slade Rooms in Broad Street.

After the renovation, the Civic and

Wulfrun Halls have continued to be an extremely popular

venue for all kinds of concerts and events. The building

received a Civic Trust Award in 2004.

|

A modern view of the building.

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|