Exhibitions Great and Small

Frank Sharman

Exhibitions are an interesting and important part of the economic, social and

cultural life of Wolverhampton. This is an outline account, mainly taken from

secondary sources. All parts of it might make interesting subjects for others to

research further.

The context of the Wolverhampton Exhibitions

The idea of holding art and industrial exhibitions, of which the Great

Exhibition of 1851 is the best known example, did not pass Wolverhampton by. Its

most notable efforts were in 1869 and 1902; but there were other examples too.

The origins of such exhibitions seem to go back to France in 1797, where the

aim of the exhibition seems to have been to sell French products, mainly to the

French, because the English blockade was making it difficult to sell them

elsewhere. But the aim was also educational and propagandist - to persuade the

French that they could produce industrial goods as well as the English. Numerous

other such exhibitions, almost exclusively French in content and character,

followed at irregular intervals until in 1849 a massive exhibition in temporary

buildings in the Champs Elysee attracted a great deal of international

attention. A number of other European countries also held similar exhibitions,

closely modeled on the French, in the first half of the century.

In the UK exhibitions of a similar character, but much smaller in scale, were

organised by what was later to become the Royal Society of Arts. Their motive

was not commercial but mainly intellectual - they were interested in encouraging

and learning about new scientific and design developments. This notion was taken

up by the Mechanics Institutes, which promoted a large exhibition in Manchester

in 1837 which was followed by many smaller exhibitions put on by Institutes in

many northern towns. The Mechanics Institutes added a new dimension to the

exhibitions - they were trying to persuade the working classes (or, more

specifically, the skilled workers, artisans and craftsman) that their products

were worthy of note and could take the benefits of modern processes and good

design. (The above is based largely on: Paul Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas: the

Exposition Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World's Fairs 1851-1939,

Manchester University Press, 1988).

Sometime during this period Wolverhampton seems to have joined in. Upton

(Chris Upton, A History of Wolverhampton, Phillimore, 1998) records: "The

earliest of these exhibitions was the brain child of George Wallis, an artist

employed by the firm of Ryton and Walton in Turton's Hall. The exhibition was

held in the Mechanics' Institute in Queen Street and showed both fine art

(including paintings by Rembrandt and Claude) and the latest in designer

furniture and decorated trays, as well as a variety of ironwork, locks and steel

toys". The inclusion of fine art in an exhibition of this period was unusual and

the mention of Claude may be significant. The decorators of japanned and similar

wares tend to look to fine art as an inspiration and exemplar. Claude was a well

known French landscapist the style and content of whose work often seems to be

reflected in the landscapes appearing on decorated wares. (I suspect that the

decoration on the relatively cheap wares produced in Wolverhampton - a town

which was an important canal centre - may have been influential in the

development of the "roses and castles" style of folk art found on canal boats.)

The Great Exhibition of 1851 seems to have taken all of the motives behind

the earlier exhibitions and rolled them together - the Great Exhibition was to

serve all the purposes of all the people. But the main organizer (with the

enthusiastic blessing of Prince Albert) added a further and vital ingredient -

that the exhibition should not just be nationally based but should be

international. Foreign exhibitors were to be important - and they came to the

1851 exhibition in droves.

| |

|

| Read about Wolverhampton's contribution

to the 1851 exhibition |

|

| |

|

The 1851 exhibition set the tone and standard for all the subsequent Great or

Universal Exhibitions which sprang up around the world immediately after 1851

and which continued throughout this century and remain with us in the form of

World Fairs. Only a few elements remained to be added. In the Paris Universal

Exhibition of 1855 fine art was added on a large scale. The 1851 exhibition had

concerned itself almost exclusively with applied or industrial art, which is, on

the whole, what we would call design and ornament. Arts for art's sake came

later. The French exhibition of 1855 also added another feature: the 1851

exhibition was housed in one huge building, the Crystal Palace; the 1855

exhibition was split between numerous pavilions; and this became the standard

practice. Indeed exhibition architecture had been invented. Many, and sometimes

all, of the buildings in an exhibition were temporary and were used as exercises

in experimenting with new architecture or making over-cooked displays of the

old. Sometimes some buildings were designed to be a permanent addition to the

townscape - Wembley Way is full of the remnants of the Wembley Exhibition, the

Festival Hall is a dour remnant of the Festival of Britain and the Atomium in

Brussels is a leftover from a World Fair. Of all the weird and wonderful

buildings constructed for exhibitions before the Great War only Melbourne's main

exhibition hall seems to have survived. (see generally: Wolfgang Friebe,

Buildings of the World Exhibitions, Editions Leipzig, 1985.

|

The main hall of the

Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne, Australia,

1888/89. This seems to be the only one of all the pre-Great War

exhibition Halls to survive. Mostly classical, slightly

frenchified, it is typical of the ornately bombastic style of

great exhibition buildings. The Eifel Tower is another reminder

of exhibitions long gone. |

One further element was required: the entertainment. The earliest fairs had

been strictly edifying in tone but the patronising classes had noted, with

amazement and satisfaction, that the working classes had flocked to the Great

Exhibition of 1851. Perhaps because of this, funfairs and the like were, for

several decades, minor parts, if officially present at all, of most British

exhibitions. But the French, again, in the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1867

tried to attract crowds by providing a funfair and also by making the exhibits

more entertaining - you could ride the helter-skelter then go and watch African

natives doing tribal dances. The great exhibitions were nothing if not

imperialist and racist. Indeed at the turn of the century the British had taken

to promoting a whole series of National Imperial Exhibitions, whose major

purpose was to defend the idea of empire. It seems that Wolverhampton hosted one

of the bigger of these in 1907. (John M. McKenzie, Propaganda and Empire: the

Manipulation of British Public Opinion 1880-1960, Manchester University Press,

1985).

Wolverhampton Exhibitions

Upton records that: "An exhibition of the Industrial Arts was held at St

Leonard's Schools in Bilston in June 1859, opened by Sir Robert Peel...".

In May 1869 Wolverhampton made a bolder step towards its own version of the

Great Exhibition, when the Exhibition of Staffordshire Arts and Industry took

place in a temporary building in the Molineux Grounds.

| The Exhibition of

Staffordshire Arts and Industry, 1869. A contemporary

photograph, with Molineux House in the right background and the

temporary exhibition building in the left background. |

|

It was opened by Earl Granville on 11th May. Upton reproduces an extract from

the Earl's speech which encapsulates much of the thinking behind such

exhibitions: he said that "it was a high distinction for Wolverhampton that its

inhabitants should be among the first to erect a building specially for

promoting industrial art. The treasures of art and the products of skilled

industry, both part and present, collected within these walls are invaluable by

suggesting ideas and planting seeds that should bear good fruit in the future,

and instill into their minds a will and taste for the beautiful and the

refined".

|

The Opening of the 1869

Exhibition. Presumably that is Lord Granville on stage,

spouting. There is an orchestra on the balcony behind him. The

large object, bottom right, seems to be most of the operative

part of a lighthouse. |

There seem to have been many other exhibitions of one sort or another in

Wolverhampton during the rest of the century, but the biggest and most ambitious

of them was the Arts and Industrial Exhibition which took place in 1902. This

great enterprise was fully in accord with all the developments in industrial

arts exhibitions up to that time, lacking only in international participation,

Canada being the only country to have a pavilion.

Mason (Frank Mason, The Book of Wolverhampton, Barracuda Books, 1979)

describes the opening by the Duke of Connaught (the King's brother): "...the

opening ceremony took place with a solid gold key studded with brilliants, and a

series of inaudible speeches. 'Its success' said the local press 'ought to be

exceed even the sanguine hopes of the promoters'. They could not have been more

in error. One of the worst summers on record ensured a loss of over £30,000 and

although some bold spirits were prepared to try again the following year, the

promoters had had enough".

The pictures here show what was on offer, as well as raising a number of

questions.

|

This colour print, from a

watercolour by George Phoenix, shows the whole exhibition. At the back

are the water chute, the Machinery Hall, the Canada Hall, the Industrial

Hall. At the right centre is the Shell Bandstand and Connaught

Restaurant. At the front are the spiral toboggan, the kiosk band stand

and the concert hall. |

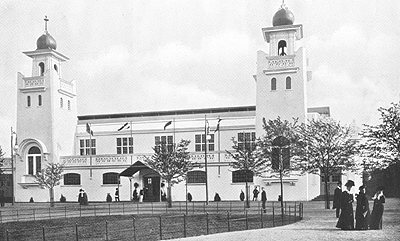

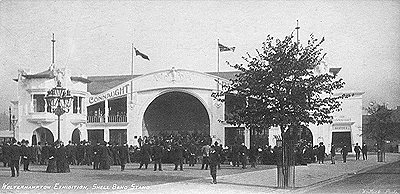

| The entrance to the site. But what

road is it on? Is it Bath Road? |

|

|

The Duke of Connaught arrives for the

opening ceremony. He is passing the Industry Hall. |

| The Industry Hall. The architectural

style - of the tops of the towers, at least - might be described as

Indo-Saracenic. The style of the rest is more debatable, though there is

a touch of art nouveau in the horeseshoe shaped entrances. |

|

|

The interior of the Industry Hall |

| The Machinery Hall. Again, the style

defies description. |

|

|

The interior of the Machinery Hall.

Compare the functional style of the interior with the oddity of the

exterior. |

| The Canada Hall. One might describe

this as stripped classical but it compares favourably with the other

pavilions. |

|

|

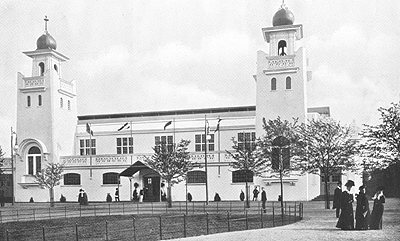

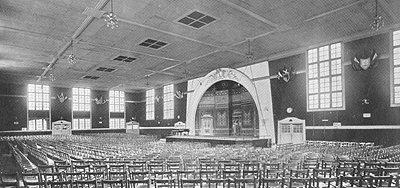

The Concert Hall. Indo-Saracenic

domes have been abandoned in favour of Eastern Orthodox onions; there

are also classical and Arabic features - quite a selection in a

basically plain design. |

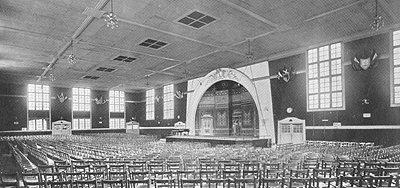

| The Interior of the Concert Hall. It

seems strangely unornamented and the seats do not seem to be designed

for comfort. |

|

|

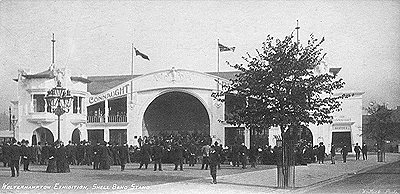

The Shell Bandstand. The doorway at

the right gave access to the Connaught Restaurant. |

|

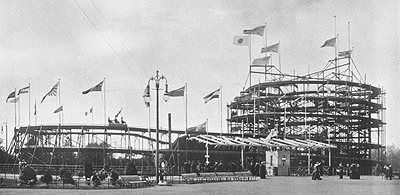

The Water Chute. |

|

|

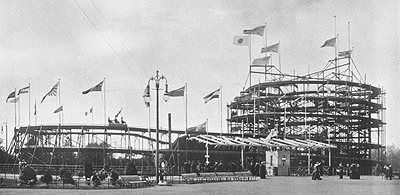

The Spiral Toboggan |

| The Swan Boats. The passengers seem

to be seated in wicker chairs. A man in sailor's uniform sits astride at

the back. How were these boats propelled? |

|

|

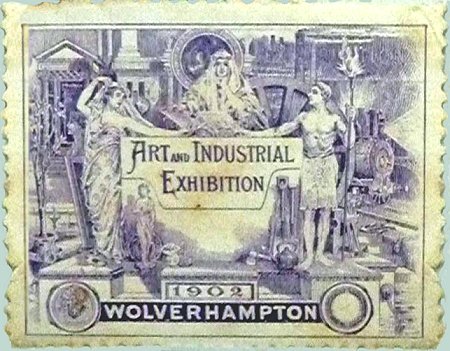

A special stamp that was produced to

commemorate the 1902 exhibition. Courtesy

of Terry Furler. |

Wolverhampton Archives, amongst other material on the 1902 Exhibition, has,

on the open shelves, a complete set of the Daily Programmes of the Exhibition,

which detail what was happening at the Exhibition day by day.

Many of the Great Exhibitions, though temporary in themselves, altered the

cities in which they took place because of the clearances and changes made to

accommodate them, because of the buildings that remained and because of changes

to infrastructure. In its own little way Wolverhampton's great exhibition had a

little effect. The underground lavatories in Queen Square were dug out to

provide for the additional visitors expected in town; the Lorain system tramway

was hurried on so as to be ready for the opening: its first route was from the

town centre to the exhibition; and the bandstand in West Park may have been

built for the Exhibition..

Some later exhibitions

The 1869 and 1902 exhibitions can be seen as being within the tradition of

art and industrial exhibitions. But, of course, Wolverhampton hosted many other

exhibitions of all sorts, local and national. It may be worth noting, briefly,

some which have come to my attention and to invite others to do further study

these, and any further examples they may find.

The Royal Agricultural Society of England had run the annual Royal Show since

1839. In 1871 it came to Staffordshire for the first time. "On that occasion the

deputation who waited on the Council of the Society to support the invitation

was introduced by Mr. C. P. Villiers, who represented Wolverhampton in the House

of Commons for the long period of 63 years, and the claim was pressed

successfully by the then Mayor (Alderman Thomas Bantock)...". (The Book of

Wolverhampton: Souvenir of the Royal Show 1937, Wolverhampton Industrial

Development Association, nd (1937). The show was held on the old race course,

now West Park.

|

The Royal Agricultural Show, 1871,

held on Wolverhampton Race Course (now West Park). In the left

background one can make out St.Peter's and the Town Hall. Is the church

just behind the stand (centre) supposed to be the Catholic Church on

Bath Road? On the right centre is the parade ring. The galleried

building left is signed "Wickham & Pickmere First Class Refreshments". |

The illustrated paper, "The Graphic", in its issue for the 21st July 1871,

published a whole page of wood blocks of the show. Three pictures are shown

here. (The other two are standard blocks of funny agricultural characters and

might have been drawn anywhere. As two of the pictures here show, "The Graphic"

seemed intent on amusing its sophisticated urban readers with illustrations of

amusing yokels).

| "Trial of Traction Engines at

Newbridge". Does anyone have the story behind this? |

|

|

In the trial fields at Hopton. What is the

machine? Is it part

of a steam ploughing set up? |

|

The Chenab (Government Steam Train) in the

Mud. Does anyone have the story behind this? |

In 1937 the Royal Show was again in Wolverhampton, this time in a very much

bigger form and at Wrotteseley Park.

These shows reflect the fact that Wolverhampton, for most of its history,

mainly got its living from agriculture. It was a centre for the rich arable

lands around as both the Exchange and the Agricultural Hall testify. In addition

Wolverhampton had been an important centre of the wool trade.

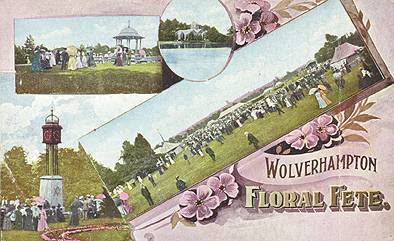

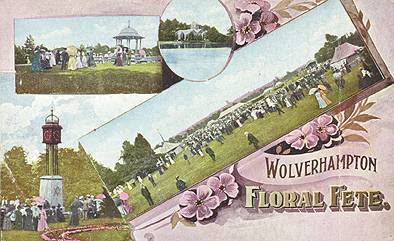

In 1937 one casualty of the Royal Show was what would have been the 45th

annual Wolverhampton Flower Show (which seems also to have been known as the

Floral Fete). This event claimed to be "in many respects ... unsurpassed for

many years and ranks next in importance to the great floral display at Chelsea."

The 1937 show was abandoned in favour of the Royal Show and this may have been,

if not the end of the Flower Show, the beginning of its end. The conservatory in

West Park is a legacy of these flower shows.

|

This undated, turn of the century,

coloured postcard, shows West Park and the clock, the band stand and the

conservatory. In the general view St.Peter's can just be made out on the

distant horizon. |

In 1951 the Festival of Britain had as great an effect on the country as the

old arts and industrial exhibitions were supposed to have, even though empire

gave way to commonwealth and the entertainment was shipped off from the South

Bank to Battersea Park. But the Festival was a festival of Britain, not just

London, and the organizing committee approved local exhibitions as part of the

Festival programme. In Wolverhampton the local exhibition, The Festival of

Wolverhampton, ran from 4th May to 19th May and was organised by Beatties, who

had 19 stands in their shop. The list of the exhibitors is almost a who's who of

Wolverhampton industry in the post war period: Express and Star, Villiers,

Goodyear, ECC, Courtaulds, J.Brockhouse and Orme Evans and Co, James Gibbons,

Butlers, Boulton Paul, Chubb, Ever Ready, Fischer Bearings, Henry Meadows,

H.J.Law, Star Aluminum, Qualcast, Guy Motors, Turner Manufacturing, Presto and

Tower Brands. (anon (Beatties), The Festival of Wolverhampton Exhibition

Souvenir programme, np (Beatties), nd (1951)). It may be a little sad to reflect

that great aspirations of 1902 had been reduced to some stands in a department

store for two weeks; and even sadder to reflect on how many of the exhibitors

are, in Wolverhampton at least, no more.

|

The symbol of the Festival of

Wolverhampton - the Festival of Britain symbol with the crossed keys of

St.Peter superimposed on it. |

|