| With the end of the Second World War

almost in sight, Wolverhampton Council looked forward to a

bright future, which included a new and very different town

centre. In 1943 the Wolverhampton Reconstruction Committee

began planning a radical redevelopment of the town including

all aspects of its social, economic, and physical structure.

The committee looked at housing, transport, markets, a new

central library, a new civic centre, recreation facilities,

a new cemetery and crematorium, and general redevelopment.

The hope was to sort out some of the town’s acute problems

including inadequate housing, traffic congestion, run-down

central areas, and the lack of playing fields, parks, and

permanent allotments. The members of the Reconstruction Committee were as follows:

Councillor H. A. White (Chairman),

Councillor T. W. Phillipson (the Mayor)

Aldermen: A. Davies,

Sir Charles Mander, Bart., and R. E. Probert

Councillors:

Mrs. A. A. Braybrook, Mr. A. Byrne Quinn, Mr. W. H. Farmer,

Mr. A. G. Goodman, Mr. J. H. Hale, Mr. C. W. Hill, Mrs. R.

F. Ilsley, Mr. J. E. Jordan,

Mr. W. Lawley, and Mrs. M.

Mackay. |

The committee was assisted by a

sub-committee under the chairmanship of the Mayor, and also

by the Borough Engineer Mr. W. Mervyn Law who submitted many

reports, and Mr. J. Brock Allon the Town Clerk. A

comprehensive social and industrial survey was undertaken,

in co-operation with Birmingham University as part of a fact

finding exercise.

The town also co-operated with the

adjoining authorities of Tettenhall, Cannock, Wednesfield,

Willenhall and part of Seisdon in the formation of a

Wolverhampton and District Joint Planning Committee.

|

From a report produced by the Reconstruction

Committee.

|

Housing

It could be seen that the most urgent

and pressing post war problem would be the provision of

houses. In the inter-war years, 16,210 houses were built in

the town, which amounted to forty percent of the total

housing stock. This included 8,978 council houses. During

the same period, 4,342 slum and sub-standard properties had

been demolished under clearance schemes. No building work

had been carried out for several years, and it was estimated

that a minimum of 6,700 houses would be needed as soon as

possible. The aim was to build 1,000 houses a year, which

would depend upon the availability of material and labour,

and the construction methods employed.

The Oxbarn Estate, a pre-war

development.

The houses were to be built following

the guidelines and plans in the 1944 Housing Manual,

published jointly by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry

of Works, and would include some temporary pre-fabricated

bungalows, four hundred of which had already been allocated

to the town. Two areas had been chosen for new housing

estates, one on the Willenhall Road where around 700 houses

were to be built, and another at Bushbury which would

consist of 1,400 homes. Plans included the construction of

roads and sewers, the provision of community buildings and

schools, and the provision of adequate playing fields in

close proximity to the houses. The retention of natural

features on the sites were an essential part of the design.

Another pre-war development, the Low

Hill Estate.

At the time, negotiations were in

progress for the acquisition of eighty five acres of rough

land between Willenhall Road and Deans Road for a third

housing estate.

Transport

Wolverhampton’s industrial development

depended upon ease of access to and from the town, for

people, raw materials and finished products. In the 1940s

there were ten major roads radiating from the town centre,

two railway stations and good depots, a network of canals

leading to the main ports, and a Municipal Airport. Shortly

before the outbreak of war, the Ministry of Transport

proposed a scheme for the building of a bypass to connect

Birmingham New Road with the A41, which could be extended to

join Stafford Road via Wobaston Road. This would have

diverted a considerable amount of through traffic, but could

have done little to relieve the congestion in the town

centre.

The increase in road

traffic between 1922 and 1938. The figures show

the average daily tonnage which is proportional

to the thickness of the black lines. From a

report produced by the Reconstruction Committee. |

The Reconstruction Committee felt that

the ideal solution would be the building of a central ring

road running from Penn Road in the south, along School

Street and Waterloo Road as far as Bath Road, then across to

Stafford Street and up Fryer Street to Victoria Square for

the bus station. The road would then go along Pipers Row,

and across to Cleveland Street, from where it joined the

Penn Road and School Street junction.

The road would provide

good access to all the major roads and the town centre. It would have an

overall width of 90 feet and consist of dual carriageways 22

feet wide, each with an 8 feet wide lay-by, allowing

standing traffic to pull-up outside the main carriageway.

There was also a central island that would be fenced so that

pedestrians could only cross the road at controlled

crossings. Roundabouts were to be constructed at each

junction, and frequent breaks in the central island would

allow traffic to turn from one carriageway to the other.

The proposed central ring

road. From a report produced by the Reconstruction

Committee. |

School Street, Waterloo Road, Fryer

Street, Pipers Row, and Cleveland Street were all to be

widened to accommodate the new road, and a new section would

be built between Wadham’s Hill and Stafford Street, and

between Stafford Street and Broad Street.

The Central

Library would be demolished to make way for the section of

the road between Pipers Row and Cleveland Street.

The main roads in and out of town were to be widened to 80 feet, and converted into dual carriageways.

The northern end of Penn

Road would be re-aligned, and Worcester Street would be

diverted. A new road would be built along Dunstall Hill from

Five Ways to Gorsebrook Road. |

One of the proposed

roundabouts with a pedestrian subway. From a

report produced by the Reconstruction Committee. |

Central Redevelopment

A Civic Centre would be built in St.

Peter’s Square with an educational precinct between the

square and Stafford Street, which would include the technical college.

For many years there had been a lack of suitable office

accommodation for the Corporations’ administrative staff who

were housed in many separate buildings throughout the town.

It was felt that the building of a Civic Centre would

overcome this problem once and for all.

The scheme involved a great deal of

demolition, including all the buildings between St. Peter’s

Square and Queen Square, and Barclays Bank. All of the

buildings in North Street from the Town Hall to Queen Square

were also to be demolished, as was Gifford House and St.

Peter and St. Paul's Church. Cheapside and Exchange Street

would disappear, and the frontages along Darlington Street,

and the eastern side of Waterloo Road were to be

redeveloped.

From a report produced by the

Reconstruction Committee.

The Retail Market had passed its useful

structural life and was in need of extensive and expensive

repairs. It was felt that a suitable site for a new market

would be on the eastern side of Market Street where many

buildings were of poor quality. It would be near the town

centre shops, the new ring road, and the bus station.

There didn’t seem to be any advantage

in building a new Wholesale Market close to the Retail

Market. The main requirements for the Wholesale Market were adequate road and

rail access, so it was suggested that the new market

should be built on land between Guy Avenue and the

railway, which at the time contained extensive cold stores

operated by the Ministry of Food. There were several railway

sidings and enough land for the building of the market, a

cattle market, and abattoirs.

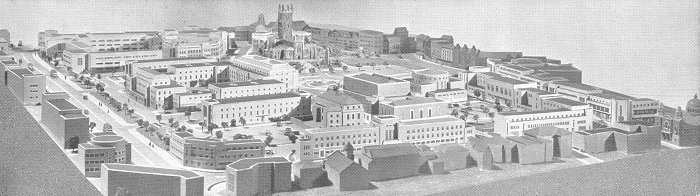

The council's model of the

proposed town centre development, looking across

Waterloo Road. On the right is Darlington Street

and the Methodist Church, in the background on

the right is Queen Square and Lichfield Street.

The central ring road is on the left. From a

report produced by the Reconstruction Committee. |

As already mentioned, the Central

Library would be demolished to make way for the ring road.

After careful consideration, the committee decided that a

new Central Library should be built on the site of the Town

Hall, in the same style as the Civic Centre.

St. Peter’s School and Institute would

be demolished to make way for the educational precinct,

allowing extensions to be built to the technical college,

along with a school of art, a little theatre with drama and

music facilities, and a county college.

The development of the new Civic Centre

would happen in five stages:

| 1. The erection of the greater part

of the administrative block, which would accommodate the

Corporation staff at present located in the Town Hall,

together with other staff distributed in the town

centre, such as Social Welfare, the portion of the

Medical Officer of Health’s staff in Exchange Street,

the Weights & Measures Department, etc. This block, which is situated on the

Market Patch, and on land in front of the present Education

Offices, could be erected without the removal of any

existing buildings, and it is recommended that it should be

proceeded with at the earliest opportunity. The completion of this portion of the

main block would place at the disposal of the police, ample

temporary accommodation in the existing Town Hall.

2. The demolition of the Retail Market

Hall and the Wholesale Market, and their erection on

alternative sites. The completion of the main

Administrative Block, and the erection of new police

buildings fronting a section of the proposed central ring

road.

3. Occupation of

new Police Buildings by the police, and

subsequent demolition of the existing Town

Hall, followed by the erection of the new Central

Library on the front portion of the site,

with provision for a car park

at the rear.

The construction of the northern

portion of the central ring road between Waterloo Road and

Stafford Street. The demolition of existing properties at

the corner of Darlington Street and Waterloo Road, and the

erection of new buildings on the site for the Electricity Show

Rooms.

4. The widening of Waterloo Road

between Darlington Street and Wadhams Hill to form part of

the central ring road. The demolition of existing property on

the east side of Waterloo Road between Darlington Street and

Wadhams Hill, and the erection of a new block of offices. The demolition of existing property on

the north side of Darlington Street between Waterloo Road

and Queen Square, and the erection of new premises

comprising shops with offices above.

5. Demolition of property between

Cheapside and Queen Square, the Conservative Club, Barclays

Bank, and Exchange Street properties.

|

|

The committee felt that the scheme

would be proof to future generations of the civic pride of

their generation, and would bring a greater sense of civic

responsibility to the local population.

The Civic Centre with a

fountain in front. On the left is the Central

Library and the Civic Hall, with St. Peter's

Church on the right. From a report produced by

the Reconstruction Committee. |

|

| |

Looking towards the Civic Centre

with the Royal London Building in the foreground, and

the educational precinct on the right. From a report

produced by the Reconstruction Committee. |

|

Recreational Facilities

The committee looked at existing

recreational facilities, and thought that Wolverhampton

suffered from a considerable deficiency for a town of its

size. In order to rectify the situation, a further 455 acres

of parks, playing fields, and playgrounds were required,

together with a further 270 acres of school playing fields.

It was realised that it was impracticable to obtain such a

large area within the town, other than by a long term

planning policy. Some areas were proposed, including what is

now Windsor Avenue Playing Fields, and Manor Road Park at

Penn, and also part of the Colton Hills, also at Penn.

The ultimate aim was to ensure that

everyone had at least one park within easy walking distance,

and each child had a playground in easy reach, without

having to cross a main road. It was felt that the amenities

in existing parks and playing fields should be improved by

planting trees and shrubs to screen the backs of adjoining

houses, and the provision of sand pits and

paddling pools for children. The larger parks and

recreational areas should have pavilions, toilets, and a

better provision of seats and shelters. Improvements to East

Park should include a boating lake, and an extension to Stow

Heath Lane.

Allotments

At the time, around 4,500 temporary

allotments were in use to help with wartime food shortages.

Few of these were expected to survive after the war, when

the land would be used for other purposes. There were also

4,621 privately owned allotments in the town. It was hoped

that after the war, a sufficient number of permanent

allotments would be available to cope with the expected demand.

A New Cemetery and Crematorium

It was realised that the existing space

at Jeffcock Road Cemetery would soon be used up, and so

steps were taken to acquire 45½ acres of land on the side of

Bushbury Hill on which to build a modern crematorium and to

lay out a lawn cemetery.

|

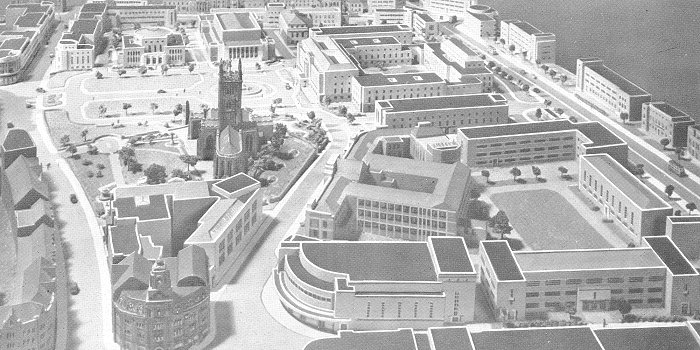

A final view of the proposed

development, looking across the technical college to

Queen Square. From a report produced by the

Reconstruction Committee. |

|

Conclusion

The cost of such a bold and

comprehensive scheme would be formidable, and could only be

carried out with the support of the general public. The

committee clearly felt that the plan would greatly benefit

the local community, and improve people’s lives.

Outcome

The plans were never implemented

because of financial restrictions, but many of the

committee’s suggestions have come to pass. The Civic Centre

is built on more or less the same site as proposed by the

committee. The Ring Road has many similarities with the

central ring road, and the educational precinct consists of

extensions to the university, and the university’s School of

Creative Arts and Design. The markets have moved, as has St.

Peter’s School, and the Police Station. The large post war

housing schemes came to fruition, as did some of the

suggestions for recreational facilities.

Luckily we still have some of the

lovely buildings that would have disappeared had the plans

been put into practice, including the old Town Hall, Giffard

House and church, Barclays Bank, and all the old buildings

on the northern side of Queen Square, and in Exchange Street

and North Street.

People still talk about the impact of

the Mander Centre in the 1960s and 1970s, and the important

losses that resulted from it. Arguably, if the scheme had

been implemented, the losses would have been far greater,

and still talked about today.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|