|

If we are nameless then who are we?

Without our names we have no individuality, no distinct

identity. At best we become an indistinguishable part of

a huge and monolithic gathering such as the Anglo Saxons

or Victorians, the peasantry or the working class; at

worst we are lost from history and become as nothing.

The desire to be known and

remembered for who we are as separate entities with a

unique character is a powerful human emotion. That is

why our ancestors, no matter how poor, strove to avoid

the indignity of a pauper’s funeral after their death.

They feared to be laid into a mass

grave with no mark above to call out who they were; they

yearned at the least for a little plot with some

memorial, no matter how small, to let the world know

that they had once been. That longing to be known and

remembered reaches out from those gone to those living

and to those yet to come. In so doing it bonds the past,

the present and the future and provides a powerful sense

of continuity in a rapidly changing society.

It is a need that motivates family

historians to seek out the names of their ancestors as

far back as possible and to find out whatever they can

about them. In that way our forebears cease to have just

existed; instead they continue to have a living

presence.

Just as family historians

enthusiastically search for their kith and kin, so too

do local historians keenly look for the names of the

earliest people to have lived in their locality. In that

search, our place names are vital for they call out to

us to hark at what they are telling us, to notice those

who gave them their names, and to understand their

meanings.

If we do but open our ears we can

just catch hold of the men and some women who are kept

alive in the names of many of our villages, towns and

cities; and we can strain to hear how they described the

features of the land in which they lived.

Spoken and written countless times

a day they may be, but yet how rarely is the

significance of our place names appreciated. They are

indeed our signposts to the past and like all good

markers, although they cannot take us on our journey,

they can show us where to go. If we truly wish to

understand who we are, and whence we come, then it is on

the path of place names that we must tread.

Some of them in the Black Country

and in the adjoining districts reach deep into the

beginnings of Anglo-Saxon England, when bands of Angles

move up the River Trent and thence its tributaries like

the Tame – settling and taking over the land from the

British. They included extended family units

who took their name from their founder or earliest

remembered ancestor. Among them was Beorma whose

‘ingas’, people, joined him in setting up a ‘ham’, an

estate or homestead. This became known as Birmingham.

Another such kinship leader may have been Esne.

He and his people, the Esningas,

set up or else took over from the Welsh, a ‘tun, a

farmstead or manor. This was recorded in a document from

996 as Esingetun. It has changed but slightly to become

Essington. Similarly Pattingham brings to mind the

estate or homestead of the people of Patta. From the

early 600s, the Esningas, Beormingas and larger tribal

groups were brought under the sway of the Kingdom of

Mercia.

|

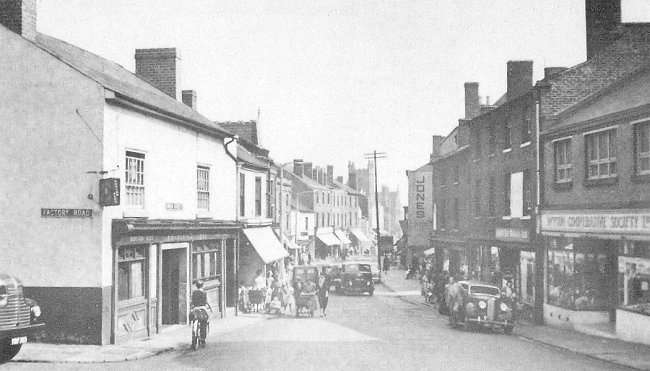

Owen Street, Tipton.

|

By then, those Welsh who remained

had intermarried with the newcomers and abandoned their

language. Most of their place names were replaced by

those in Old English and have forever disappeared. These

were added to with new settlements which had Old English

names from the beginning. Then there were those places which

may once have been called after a feature in the

landscape but which were renamed after a man who was

given overlordship of a manor.

Darlaston and Tipton fall into this

latter category. The ‘tun’ element means a manor and

experts have placed its common use to the period between

750 and 950. Thus Darlaston signifies the manor of

Deorlaf. The second earliest recording of it in 1262

spelled it as Derlaveston, although by 1316 its modern

form had emerged when it was given as Derlaston. As for

Tipton, it was first noted in the Domesday Book of 1086

and was put down as Tibintone, meaning the estate of

Tibba.

Willenhall is mentioned much

earlier and it is one of the earliest Black Country

place names cited in a document. In 732 it was given as

Willenhalch and as such was the ‘halh, small valley, of

Willa. Sedgley and Dudley are two other places that

remember a person. Both signify a ‘leah’ or ley, a

clearing – the one of someone called of Secg and the

other of a fellow named Dudda.

Both places are among a noticeable

number to the west of Birmingham which have this element

‘leah’ and which suggest that there was a growth of

settlements through clearings in a woodland environment

from about 750 to 950. They include Bradley, which meant

the ‘braden leah’ board clearing; Rowley, which was ‘the

ruh’, rough clearing; Horsley Heath, which had horses in

it; Bentley, which had bent grass; and Langley. This

means the ‘lang’ clearing and it would have emerged when

the local folk said lang instead of long, as they do

still in the lowlands of Scotland and parts of the north

east of England.

There are also several names which

may be connected to a man. Amblecote means either the

‘cot’, cottage, of the ‘aemel’, caterpillar, or else the

cottage of someone called Aemela. Bloxwich possibly

recalls the ‘wic’, farm, of Blocca.

|

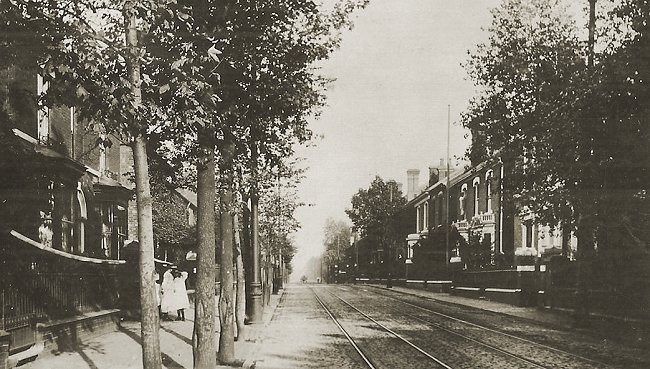

New Road, Willenhall.

|

It is likely that Cradley means the

clearing of Cradda or Cradel, or perhaps the clearing

where cradles were got for the making of hurdle fencing.

Cradley Heath is the heathland named after Cradley.

Other place names tell us of the landscape of the West

Midlands a thousand years and more ago. When the Angles

took over the region from the Welsh, they looked with

fresh and open eyes upon the physical features that they

saw and named them accordingly.

At Caldmore the incomers

experienced a cold marsh, while at Shelfield they

spotted a ‘scelf’, a ledge or plateau on a hill.

Shelfield does indeed stand on a plateau with slopes on

all sides and it was originally given as Schelfull in

documents from the Later Middle Ages.

Elsewhere in what is now the Black

Country, there are a marked number of place names ending

in ‘al’ or ‘all’, from the Anglo Saxon word ‘halh’. This

had different meanings but in the West Midlands it was

most used to describe a shallow valley. Today it is

often difficult or indeed impossible to make out such a

nook, because urbanisation and development have too

often destroyed or obscured the original lay of the

land.

However, the valley associated with

Walsall is still visible. Although its parish church, St

Matthew’s, lies upon a limestone hill in the centre of

the modern town, the ground falls away on all sides and

there is a noticeable dip in the Bridge Street area,

where the Walsall Brook flowed. The borough of Walsall

boasts other place names including halh: Pelsall, Peol’s

nook; Rushall, the nook with rushes in it; and Blakenall,

which may mean Blaca’s nook or else the settlement at

the black nook. Further south is Halesowen, which for

many years was simply Hales – the nooks. Certainly,

coming down Mucklow Hill and with the Clent Hills before

you, it is obvious that Halesowen does lie in a

pronounced dip.

Gornall, both Upper and Lower, may

have ‘halh’ in their names but their meaning is

difficult to fathom out. Some place-name experts feel it

denotes the ‘cweorn-halh’, the water mill. However, as

David Horovitz makes plain in his outstanding work on

The Place-Names of Staffordshire, neither of the Gornals

is in a shallow valley, and Upper Gornal is on high

ground.

However, ‘cweorn’ could also mean a

place where mill stones were got and in 1801 it was

stated that excellent grind stones were dug at Cotwall

End nearby. Cotwall itself signifies the ‘cot’, cottage,

by the ‘waelle’, spring.

Ettingshall is definitely a ‘halh,

and is either the small valley of a man called Etta or

else is the ‘etting’, grazing place. It belonged to

Bilston, which was first written as Bilsetnatun. This spelling provides us with the

full meaning of the name. The old belief was that it

meant the ‘tun’, the estate, of Bill’s folk. In fact, it indicates the

settlement of the ‘saete’, folk, of the ‘bile’, meaning

the sharp ridge or pointed hill. There is a possibility,

however, that the Bil part may come instead from ‘bill’,

meaning a sword or a physical feature that was

sword-shaped.

The name Warley is not so easily

explained. Some experts feel that it is the clearing

associated with a stream called Worf; others assert that

it is derived from either the Anglo Saxon word

weofeslege or else weorfalege, both of which would

indicate a clearing for cattle.

Wordsley is another place that

pulls us inexorably both into the nooks and crannies of

English history and into the peculiarities of our place

names. It is a clearing that could be derived from the

Anglo-Saxon word wulfweardes, meaning wolf guard. For centuries Wordsley was part of

the large parish of Kingswinford. Originally Swinford,

the ford of the swine across the River Stour, it later

gained the prefix King when it became a royal manor.

Nearby Oldswinford belonged to Amblecote and was named

Old to distinguish it from Kinsgwinford. A bridge later

replaced the ford for crossing the Stour, hence the name

Stourbridge.

The woodland setting of much of the

Black Country is emphasised by clearings associated with

trees. Brierley Hill was the thorny clearing on the hill

– thorny because of the briars and brambles thereabouts. At West Bromwich the Anglo-Saxons

saw that broom trees were plentiful and placed a ‘wic’,

a farm, amid them. Interestingly, many older people

still refer to it as Bromwich or Bramwich and it was

first given as just Bromwic in 1086 – not being recorded

as Westbromwich until 1322. |

High Street, Aldridge.

|

Another farm was placed amid the

alders – hence Aldridge. This is the correct meaning as

indicated by the oldest spelling Alrewic. It is not the ridge of alders as it

may seem. As for Woodsetton, this was either the

woodland ‘seten’, plantation, or else the animal fold in

the woodland, while Coseley was the clearing from which

‘col’, charcoal, was obtained.

Just as Aldridge can appear to mean

something it is not, so too can Great Bridge. There is a

bridge there across the Tame that connects Tipton and

West Bromwich but the Great part of the name does not

mean big. It comes from the Old English word

‘greot’ meaning a gravelly place. Place names such as

this are not only fascinating but also they are

important clues to who we are and whence we come. |

|

| Return to

Black Country Towns |

|