|

Introduction

The Saxon Cross Shaft, minus its

surmounting cross, in St. Peter’s Gardens (previously

churchyard) is the oldest relic of Wolverhampton’s early

history and the most ancient edifice in the West Midland

Conurbation, yet many Wulfrunians do not seem to be

aware of its existence. It has witnessed incredible

changes in the development of the town since it was

first raised on the highest point in the town centre, a

position it has occupied ever since. Probably one of the

most dramatic events to take place in its vicinity was

the rout of the Danish army in 910/911AD at the Battle

of Tettenhall, or was it Wednesfield or both? Our cross

might have heard the clamour of the battle possibly

safely protected by Heantun’s defensive palisade,

depending of course on its hotly disputed age. |

|

The Saxon column in St. Peter’s

Gardens. |

Much has been written about the

cross shaft, with a considerable amount available on

line but it could be said to have had mixed appraisals:

some writers on Saxon sculpture ignored it altogether

but T. D. Kendrick writing in 1938 called it ‘The

noblest monument of its kind that has come down to us’:

he regarded it as unique and the only surviving example

of the southern continental Baroque style from the ninth

century.

The most authoritative recent

accounts are those written by the late Mr. Michael M.

Rix staff tutor in architectural history at the

extra-mural department of Birmingham University, and

more recently a study by Professor Jane Hawkes of York

University. Michael Rix’s article was published by the

Royal Archaeological Institute in its journal of June

1962 and Jane Hawkes’ study is in the recently published

(2018) Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture for

Derbyshire and Staffordshire. This article makes use of

information from both publications together with some

additional comments and observations. |

|

Historical

background

In the sixth and seventh centuries

peripatetic Celtic priests would establish preaching

locations and would carry with them their wooden staff

with its cross head, to plant on the ground whist they

addressed their listeners. Depending on their success a

fixed wooden cross would be erected on the preaching

site which in time would be replaced with a more

permanent stone cross. These crosses almost invariably

predated the foundation of a church on the same site and

the subsequent church would usually be built immediately

to the north of the cross to prevent the church’s shadow

from falling on the cross. The date of any wooden cross

in Wolverhampton will never be known, and the date of

its stone replacement is a matter of considerable

dispute. |

|

Michael Rix comments: - ‘The

Wolverhampton Cross deserves a distinguished place in

any catalogue of Anglo-Saxon art by virtue both of its

scale and the quality of its decoration. Its position is

also focal in any study of the fifty and more

cylindrical-shafted carved crosses of this period’.

The Wolverhampton cylindrical cross

shaft was for long a source of dispute among experts of

pre-Norman Conquest sculpture. Disagreements arose over

its original purpose and creation date: was it pagan or

Christian? Danish or Saxon? did it date from the late

12th.century or the mid-9th? The air has cleared over

the last 80 years and it is now known to be Saxon in

origin and created within an approximately 100-year time

frame. It deserves a distinguished place in any

catalogue of Anglo-Saxon art and is one of more than two

thousand or so cross shafts of the Saxon period around

Britain most of which exist only as fragments, it is the

only complete Saxon monolithic circular column remaining

in the country.

Despite being ignored by some

writers it was considered important enough to have a

plaster cast made from it in 1877 from a mould made by

Sergeant Bullen of the Royal Engineers. The cast was

placed in the Great Cast Hall of the Victoria and Albert

Museum where, ironically it was placed next to a cast of

Trajan’s Column from Rome, somewhat undermining its

grandeur. Unfortunately, the cast is now in storage

following reordering of the Cast Hall.

The casting of the Wolverhampton column proved to be

most fortuitous: whilst the real column has suffered

badly form pollution and weathering over the last 140

plus years, the cast obviously has not and was used in

1913 by Dorothy B. Martin as a source for an extended

drawing of its carved decoration. |

Plaster cast in the Victoria and

Albert Museum. |

|

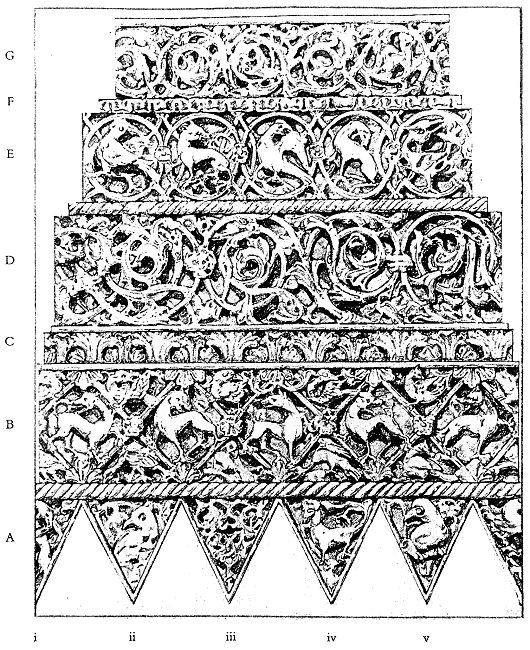

Extended drawing of ornament on

the column by Dorothy B. Martin. 1911. |

The column is approximately 4.3 metres (14 feet)

tall (its precise height is concealed by the more recent

supporting stones around its base) and varies in

diameter from 0.76 metres (30 inches) at the base to

0.56metres (22inches) at the top, immediately under the

cap. Early writers believed it to be of post Conquest

date but this view changed in the 1930s when a date of

994 was suggested, to coincide with the foundation,by

Lady Wulfruna, of St. Peter’s Church as a minster,

however this event is considered somewhat dubious by

Professor Hawkes in her recent study.

In 1938 T. D. Kendrick in his book ‘Anglo Saxon Art

to AD 900’ pushed the date back even further to the

middle of the ninth century, a date postulated by

Michael Rix in his paper, following extensive research.

|

|

That date has now been modified

again by Professor Hawkes who believes early to

mid-tenth century is a safer estimate. She tells us that

despite its long history there is no recorded mention of

it until 1794 when it was discussed in a letter to the

Gentleman’s Magazine, although it is shown on Isaac

Taylor’s map of Wolverhampton published in 1750.

The dating of the column is based

mainly upon the style of decoration carved around its

circumference, it comprises predominantly typical pre

Danish (Viking) era ornamentation, consisting of bands

of exuberant swirls of foliage between bands of frisky

Anglian beasts with their heads turned looking

backwards, all carved with supreme skill. More

importantly it has two bands of Acanthus leaf decoration

that provide the principal basis for its dating.

Artistic Inspiration

It was suggested in Mr. Rix’s

article that the designs of many Saxon cross shafts,

circular and rectangular, were based upon the wooden

staff rood of the early missionary that was planted as a

rallying point and for use as a preaching cross. This

suggestion arises partly from the pendant triangular

forms at the bottom of the decoration on some cross

shafts, including the Wolverhampton column, matching

those found on fragments of metalwork from early cross

staffs. The foliage and animal decoration are also a

common feature on both the metalwork attached to wooden

staffs and some stone crosses. The decoration on the

Wolverhampton column exhibits a degree of undercutting

matching the filigree metalwork popular in the ninth

century. This led Mr. Rix to suggest that this type of

metalwork was the direct artistic inspiration for the

carving on the column.

Some of the animals on the

Wolverhampton column are similar to those on items of

metalwork found in the Trewhiddle hoard, discovered in

Cornwall in 1774. Coins found in the hoard date these

items to the third quarter of the ninth century, so

leading Mr. Rix to propose a similar date (850 AD.) for

the carving on the Wolverhampton column but within a

fairly wide stylistic period.

Mr. Rix also identifies other

similar and well-known crosses and fragments of the same

period. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner relates the Wolverhampton

column to cross fragments at Masham and Dewsbury, both

in Yorkshire, grouping all three as Mercian types

because of their circular section, and dating them to

the early 9th century.

Professor Hawkes, as mentioned

above, believes the column relates more to the

Benedictine Reform period in the middle of the 10th

century. The date range of 850 to 950 AD is determined

predominantly by the use of Acanthus leaf decoration as

discussed below.

|

|

The Acanthus Factor

One of the more interesting

features of the ornament and possibly unique to the

Wolverhampton column are two narrow bands of Acanthus

leaf decoration and Acanthus leaves attached to the

exuberant grape vine scroll in the wider bands, an

artist’s botanical hybrid! ? |

|

|

Band of Acanthus Leaf

decoration. |

| It is the use of Acanthus foliage that provides

the clue to the age of the column, but paradoxically

it also leads to the discrepancy in dating. The

acanthus leaf was a popular decorative motive in

classical Greece and Rome and would have been seen

in this country during the Roman occupation but

being a Mediterranean plant, it normally played no

part in Saxon work. It did not appear in general use

again until the end of the twelfth century. Early

20th. Century historians saw these decorative bands

on the column as an example of this reintroduction

and dated the column accordingly to the third

quarter of the 12th.century. |

|

Roman acanthus detail: Jordan. |

| The earlier Saxon dating suggested by T. D.

Kendrick in 1938 was based partly on the knowledge

that the acanthus leaf did make two brief

appearances well before the 12th century and could

have been used by our accomplished sculptor for his

‘rather wild acanthus ornament’ (Nikolaus Pevsner’s

description ). Its first reappearance was the result

of Carolingian influence from the continent during

and just after the reign of Charlemagne the Great.

In the year 800 A.D. Charlemagne was created Holy

Roman Emperor, by the Pope, who resurrected the

ancient title especially for him after it had lain

dormant for many centuries. To celebrate his newly

acquired title Charlemagne built a new octagonal

chapel at his palace in Aachen in Germany, now the

Cathedral, and to emphasise his new link with Rome

he imported some ancient columns from Rome and

Ravenna to utilise in its construction. These came

complete with their Corinthian capitals that

incorporate Acanthus leaf decoration and so the

Acanthus was reintroduced into northern Europe. This

Carolingian Renaissance became a strong influence in

European culture and the acanthus leaf began to

appear in architectural detailing and in decorative

manuscript work on the continent. Charlemagne

enjoyed friendly relations with King Offa of Mercia,

whom he called his ‘brother’. Offa’s daughter

married Charlemagne’s son and they exchanged court

representatives, so inevitably there would have been

some cultural influence on the Saxon court. Although

Offa died in AD 796 that influence could have

endured into the 9th.century. It has been suggested

that Offa might have received from Charlemagne a

present of a decorated missionary’s staff after

Offa’s visits to meet the Pope in Rome, when he

sought to follow in Charlemagne’s footsteps. Even so

the Acanthus leaf does not seem to have ventured

across the English Channel to any great extent and

did not become part of the Saxon catalogue of

decorative motifs at that time. The only surviving

examples of its use in the mid-9th.century in this

country appear to be on the border of a manuscript

in the British museum; on a few Saxon coffin lids

and, according to Michael Rix, on the Wolverhampton

cross shaft, allowing, of course for other examples

that could have subsequently disappeared. |

|

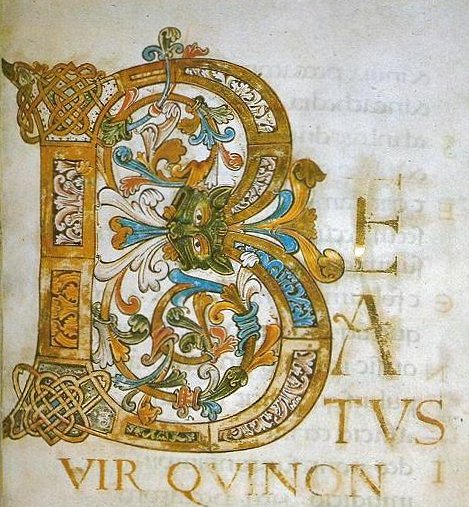

The Ramsey Psalter: late 10th.C. |

The acanthus failed to take root in post Offa Saxon

Britain and was not seen again until the middle of the

tenth century when it arrived as part of the cultural

ethos that accompanied the Benedictine Reform Period.

These reforms were introduced by continental monasteries

on the direction of King Athelstan, who was guided by

the English bishops including Aethelwold, Bishop of

Winchester. Aethelwold established artistic workshops

including manuscript illustration and sculpture where

use was made of the acanthus leaf alongside traditional

Saxon motifs. Professor Jane Hawkes believes it was this

school of design that inspired our sculptor. |

|

It is difficult for us today to

appreciate the artistic dichotomy that the carving on

the Wolverhampton column illustrates, not unlike

inserting a strip of Art Deco decoration into a Robert

Adam classical frieze. It is unlikely we will ever know

what prompted our gifted Saxon sculptor to include bands

of classical acanthus decoration within his brilliant

traditional and lively Saxon carving. One thing is

certain; the confident exuberance of his carving

displays great skill with a well-developed design

aptitude: qualities perhaps more applicable to the later

Saxon date of 950 than the earlier one of 850.

Certainly, the carving has a

confidence and quality that suggests a long period of

development, similar to some manuscript work: in

particular on the well-known Ramsey Psalter of circa

970; where acanthus scrollwork within the loops of the

ornate capital letter ‘B’ adjoins typical Saxon

interlacing.

The acanthus leaf has probably been

the most enduring architectural motif of all time; from

its traditional carved inception by the great Greek

sculptor Callymachus around 350 BC, it was never out of

use until the beginning of the 20th. Century. If you

stand by the cross shaft and look toward Barclays Bank

you will see a continuous acanthus moulding running

around the 1870’s building, 1000 years or so later than

the moulding around the cross shaft.

The Uriconium

Connection

It has been established that the

geological composition of the stone from which the

column is made is a hard, moderate to fine grained

sandstone quite unlike the sandstone in the

Wolverhampton locality which is coarser and more

friable. There is a tradition that the Wolverhampton

column is a recycled column from the Roman city of

Uriconium in Shropshire, some twenty miles to the west.

Dr. Roger White of Birmingham University, who wrote the

official guide to Uriconium, tells us that much of the

hard fine grained sandstone used in the city came from a

quarry at Hoar Edge near the Lawley Hill, eight miles to

the south of the old city. The tradition for the

column’s Roman origin is strengthened by its profile: it

has a subtle entasis (slightly curved convex outline)

synonymous with the aesthetic refinement of classical

columns generally but not seen on any other Saxon round

columns except for their short round window balusters

that are usually excessively curved. |

|

Uriconium Baths Basilica, showing

the position on the floor of lost columns. |

|

Dr. White suggests the

Wolverhampton column could have come from the Baths

Basilica adjoining Watling Street where the street

passes through the centre of the city. Part of the

external wall of the basilica, known as ‘The Old

Work’, still stands and forms the most dramatic

structure remaining in the city. He confirms that

there were 24 columns and bases inside the basilica,

and he believes some of these could still have been

upright in the middle of the ninth century. All the

columns and bases have long been removed from the

basilica by stone robbers, as were all the other

columns in the city including those at the entrance

to the Forum opposite to the basilica, but the bases

to the Forum columns still remain in a trench

excavation alongside Watling Street. Some writers

have suggested that the Wolverhampton column came

from the Forum. There is a problem with both of

these suggestions: first the remaining bases in the

forum are too small to fit our column (45 cms. and

61cms. diameter as opposed to 76 cms. diameter for

the Wolverhampton column) and the columns in the

basilica were much taller than our column but one

could have been reduced in height deliberately or

accidentally. Interestingly Dr.White reports that a

Saxon strap tag (metal belt fastener) of the 9th. or

10th. Century was found in the recently re-excavated

robber’s trench, in the south aisle of the basilica:

did a Saxon stone recycler burst his belt buckle as

he strained to move a column base!?

Another detail linking the

Wolverhampton column to the Roman remains is the

method of connecting columns to bases using the

mortice and tenon technique where a large square

dowel could have been used to connect the stone

members together. 100mm Square holes can clearly be

seen in the remaining bases of the Forum colonnade

and match precisely the 100mm. square hole in the

top of the cap on the Wolverhampton column:

suggesting a standard procedure for fixing the

column capitals and bases.

Dr. White believes the columns

in the basilica would have been of the Corinthian

order and tall enough to match the height of the

‘Old Work’. The Corinthian order was generally used

in the more important buildings. If you needed only

to support a simple roof the Tuscan order would have

been the column of choice. It was the last of the

five Roman orders to be developed and would have

been the cheapest and easiest to produce (it is

often seen today in fibre glass form flanking the

entrances to modern houses.). There are reasons to

suggest that the Wolverhampton column was of the

Tuscan order and not the Corinthian. All the Roman

orders had their specific proportions and those of

the Tuscan order seem to fit our Saxon shaft The

upper diameter should be three quarters of the lower

diameter (Wolverhampton, 22inches to 30inches; (

56cm. to 76cm.) : the height of the column should be

six times the lower diameter ( therefore our column

should be 15 feet (4.57m.) tall. It measures only 14

feet which seems to be an inconsistency, but this

could be explained by the necessity to sink the

column into a circular mortice in the huge plinth

stone. The plinth is 6 -7 feet in diameter and 1

foot 9 inches deep. A one foot (30 cms.) deep

mortice would seem to be an appropriate depth into

which to fit the column to guarantee its stability,

making it a perfect fit for the Roman Tuscan

proportions. The plinth stone weighing approximately

4 tons, appears to be of a coarser grained stone, it

is very weathered and presumably came from a local

source. It should also be noted that Corinthian

columns generally had fluted shafts: the un-sculpted

lower section of our column does not. |

|

Wroxeter Church font. |

|

The column weighs approximately

3.6 metric tons so dragging it to Heanton, probably

initially along Watling Street, must have

represented a considerable physical feat as well as

a strong act of faith. It is generally agreed that

it would not have been re-carved until it had been

erected on its present site.

The Wolverhampton column

appears to be unique in one other respect, it is the

only monolithic Roman column in Britain that has

probably been standing since it was first erected

nearly one thousand nine hundred years ago, apart of

course from its brief journey to Wolverhampton.

There is another Roman Tuscan column standing in

front of York Minster, but this was dug up as

fragments from under the central tower during

underpinning work and re-erected in 1969. There are

two small columns forming gateposts at Wroxeter

church, but they were excavated in the 19th.

Century.

Of those column bases remaining

at Uriconium just one would fit the Wolverhampton

column perfectly. It lies just within the walls of

the old city located inside Wroxeter church and was

inverted and hollowed out in the Saxon period to

form the church font.

Finally, in considering the

dimensions of the cap stone on the Wolverhampton

column it is noticeable that these are what would be

expected if it was the original Tuscan capital,

allowing for the Saxon re-carving The cap has the

standard 4 inch (10 cm.) square mortice recess on

top, referred to above, now filled in with mortar.

It split at some time in the past and has been

repaired: it is tempting to speculate that the split

occurred when the crosshead separated from the

column, although it could equally be due to frost

damage.

The Problem of

Visualisation

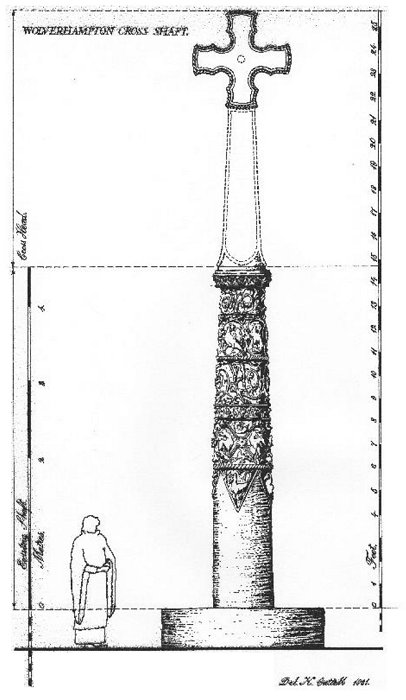

In his study of the column,

Michael Rix was keen to provide a visual

reconstruction showing the possible original

appearance of the complete cross. He knew of the

existence of a cross head of the mid ninth century

only 34 miles away. This is the Saxon Cross head in

St. Michael’s church in the village of Cropthorne,

Worcestershire that was discovered buried in the

interior of the chancel wall when building repairs

were being carried out and proved to be relatively

undamaged. It is heavily decorated on the front and

back with animated beasts and birds in bold trails

of vegetation, not identical to those on the

Wolverhampton column but similar in character.

Strangely the edges of the arms are decorated with a

Greek key pattern. |

|

Mr. Rix considered that something similar to the

Cropthorne cross head was as close as we were likely

to get to the cross head that stood on the

Wolverhampton column so a drawing was prepared

showing the column with the Cropthorne cross

superimposed. This drawing was submitted to Mr. C.

A. Ralegh Radford who in Michael Rix’s words was

‘The uncrowned king of pre-conquest studies.’ at

that time. He rejected the drawing because in his

opinion the cross would have been modelled on the

missionary’s staff or rood as were other crosses of

the broader period, e.g. Leek; Ilam; Brailsford in

Derbyshire; Penrith and Beckermet in Cumberland and

many other smaller fragments in various part of the

country. All of these crosses had square tapering

shafts of varying lengths connecting the top of the

column to the cross head.

A second drawing for the Wolverhampton cross was

prepared early in 1962, showing a tapered shaft

between the column and the superimposed cross and

this became the accepted assessment of its likely

appearance.

Unfortunately, there is one major problem with

this assumption and that concerns the question of

structural integrity: by far the majority of other

examples are or once were monolithic structures

whereas the Wolverhampton cross was a composite

structure with at least three separate components.

Monolithic structures are much more resistant to

lateral stresses than a jointed structure which is

only as strong as its joints. |

|

During high winds a cross with

a long tapered shaft would have exerted excessive

leverage on the joint at the top of the main

existing column: our sculptor would have been aware

of this problem and would have been unlikely to

create a structure in an elevated position that

would be likely blow over in a severe gale.

Unfortunately despite close

examination of the column on several occasions and

photographic records being taken, no one seems to

have measured the depth of the mortice on the boss

before it was filled with a waterproof composition:

knowing its depth might have given a clue to the

height of the original superstructure.

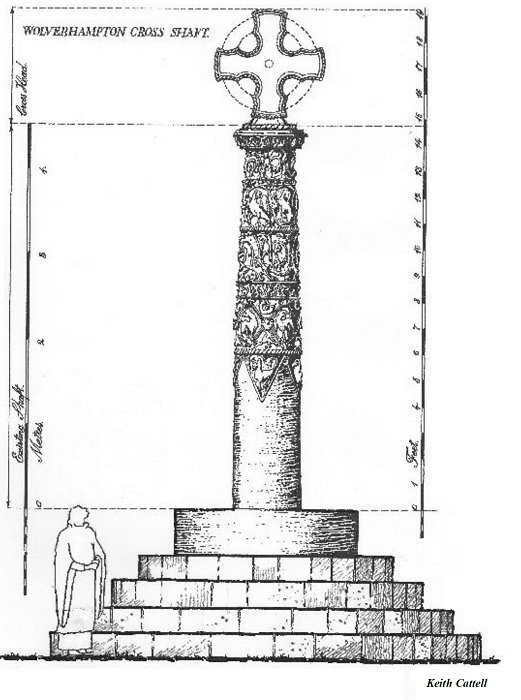

Professor Jane Hawkes has

suggested that the initial depiction of our column,

showing the cross sitting directly on top of the

main column, is the most likely representation of

its original appearance. The revised drawing below

is similar to the first illustration, and I believe

should now be considered as its more likely original

appearance. |

|

| When speculating on the size of the lost cross, one

key factor would be uppermost in the mind of the

sculptor, he would need to find something he could use

consisting of the same hard sandstone as the column: an

obvious choice would have been the circular column base.

We know the size of these from the Wroxeter font and a

cross carved from such a base would have been only two

or three inches shorter than the Cropthorne cross. This

of course is only speculation. The

stepped base shown in this illustration is determined by

the findings from the excavation made in 1949 under the

supervision of Michael Rix. The existing ground level

coincides approximately with the top step and indicates

how much the ground has risen as a result of centuries

of burials. The original ground level would have been

much the same as the level

of the adjacent existing pathway to the church porch.

Colour

In our multi coloured world we can

appreciate the beauty of natural stone sculpture but our

medieval ancestors who lived in a less colourful world,

valued applied colour and would use it where they could

afford to do so. Richard Bryant, a specialist in Saxon

painted sculpture who has made a close study of the

Saxon paintwork at Deerhurst Saxon Church in

Gloucestershire, is firmly of the opinion that our

column would have been painted when it was first

erected. Not quite as colourful as a Totem Pole because

the colours would have been restricted to the earth

colours, Yellow Ochre; Brick Red; White and possibly

Black. Blues; Greens; Purple; etc., would probably have

been unobtainable or too expensive.

When and where did

the Cross Head go?

Perhaps the question should be,

‘Did it fall or was it pushed’. Hundreds of crosses

throughout the British Isles have disappeared or remain

only as fragments and many of those will have been

deliberately destroyed. Mr. Michael Rix believed the

Wolverhampton cross head was probably removed during the

Puritan Commonwealth period, although he does not say as

much in his article. It is on record that the famous

nonconformist Richard Baxter of Kidderminster tried to

remove the cross head from the column in Kidderminster

during the Commonwealth period, but his ladder proved to

be too short and while he went to find a longer one a

crowd gathered and prevented him from knocking it to the

ground on his return. Such an attempt might have been

made on the Wolverhampton Cross because the rector at

St. Peter’s Church during the Commonwealth, the Rev.

John Reynolds, may well have had similar inclinations:

he was ejected in 1662 as a result of his Puritan

leanings.

There is evidence that once removed

some cross heads were treated with respect. Several

including that at Cropthorne, have been found built into

the structure of their church and others may be waiting

to be discovered, but whether this was an attempt to

preserve them or just to make use of them as building

stone is a moot point. It could be argued that if they

were treated only as a convenient source of stone they

would have been broken into more manageable pieces.

Again, at Wroxeter church in Shropshire part of a Saxon

cross shaft has been built into the external face of the

south wall of the nave in such a position that it seems

to be ‘on display’.

Not knowing the nature of the

tragedy that befell our crosshead it is not beyond the

realms of possibility that it could reappear again at

some time in the future during church building repair or

excavation works.

Future Conservation

of the Column

From time to time over the last

fifty years consideration has been given to preserving

the column before it erodes even further. A study in

1998 by Cliveden Conservation Workshops Ltd. discovered

that the stone was corroding not only externally but

also internally and will continue to do so. Proposals

have been put forward to move the column into St.

Peter’s church but much importance is placed on the fact

that it has stood in the same position for the last 1100

years or so, a view backed by English Heritage who felt

something would be lost if it was moved, even if a

replica was placed in the same position. Another

suggestion was made to place a protective cover over it,

probably the best compromise but one that would call for

a very sensitive design solution. A proposal was put

forward in 1977 by the Wolverhampton Society of

Architects to excavate around the column to expose the

original ground level and the steps as part of a general

conservation project but this was not acted upon.

A relatively simple improvement

could be made to the column’s appearance by removing the

rubble stonework around its base, that was obviously

placed there as a very crude method of preventing the

column from falling. This was carried out at some

unrecorded date, probably in the late eighteenth or

early nineteenth century.

We owe it to future Wulfrunians to

do something to preserve this Saxon Christian work of

art that is important not just for Wolverhampton but as

the West Midland Conurbation’s oldest Christian

monument.

Timescale of Events

100 AD. Approx. Roman column shaped

and carved, possibly for the interior of the Baths

Basilica at Uriconium. (Dr. Roger H. White) or the Forum

(Gerald P. Mander MA. FSA.)

850 - 950 AD. Approx. Column

brought from Uriconium to Heanton.

1649-1660. Commonwealth: danger

period for Christian iconography. Possible loss of cross

head?

1751. Shown on Isaac Taylor’s map

of Wolverhampton minus the cross head.

1877. Plaster cast taken for the

Victoria and Albert Museum.

1877. Charles Lyman comments:

profile of column not Norman but has classical entasis.

1949. Excavation around base on the

eastern side of the column, by Michael M. Rix, reveals

decayed remains of four steps.

1953. Fractured capital cramped

together.

1962. Article by Michael M. Rix for

The Royal Archaeological Institute.

1990. Inspection of the cross shaft

by Richard Marsh Conservation.

1992. An archaeological assessment

by Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit,

including a re-excavation on the east side of the

column.

1999. The column cleaned and

repaired.

2019. Article by Professor Jane

Hawkes for the Corpus of Anglo Saxon Stone Sculpture.

Acknowledgements

This article could not have been

written without the generous contributions of the

following professional historians and I am duly indebted

to them.

Michael Rix MA.

Professor Jane Hawkes

Dr. Roger H.White.

Richard Bryant |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|