|

St. John's Church History

by John Roper

|

|

|

The first half of the 18th century had

seen very considerable changes in the development of

Wolverhampton. Nat the least 'Of these had been the enormous

growth of such long established trades as lock making and

buckle making, with the result that in the 1750's we read of

the town as a ‘large and populous trading place,’ with a

steadily rising number of inhabitants. Isaac Taylor's Map of

Wolverhampton, which first appeared in 1750, gives us a good

idea of what this growing town looked like, with its closely

congested area round the High Green market place and its

projected new streets and sites for building on the

immediate outskirts.

An increase in church accommodation had

not, however, gone hand-in-hand with the town's development.

The Collegiate Church (St. Peter's) had still to cater for

the needs of the whole of Wolverhampton, and what is perhaps

even more significant, so had its churchyard, which was

rapidly becoming inadequate.

The only solution was the provision of

a new church and burial ground, and to this end a voluntary

subscription had been entered into somewhere about the turn

of the century, and a favourable site, on the western side

of the town, had been offered. Contributions arrived slowly,

however, and little progress seems to have been made with

the proposed scheme until about 1754 when the Earl of

Stamford offered to give the sum of £1,000 to the building

fund on condition that he and his successors might have the

perpetual right of presentation to the living of the new

church. There were however several practical difficulties to

be overcame before his offer could be accepted. One of these

arose from the necessity of obtaining a private Act of

Parliament because of the condition imposed by Lord Stamford

on his gift, and a certain amount of delay unavoidably

occurred before this received the Royal Assent in 1755 and a

start could be made.

The numerous provisions of the Act were

to be carried out by trustees or commissioners: 34 of these

are named and in addition, any person who contributed £20 or

more to the building fund automatically qualified as a

trustee and his name was added to the list. At their head

was the Dean of Windsor and Wolverhampton Dr. Penyston Booth

who had already shown great enthusiasm in the building or

re-building of churches in his vast parish, notably at

Wednesfield in 1746, at Willenhall in 1748, and at Bilston

in 1753.

Among the other names we find those of

William Archer who was later to provide £200 towards the

purchase of the famous Renatus Harris organ; a factor,

Rowland Carr of Queen Street; an upholsterer, James Eykyn;

four ironmongers including the celebrated Benjamin Molineux

of Molineux House: and one of the early Wolverhampton

japanners, Thomas Wightwick of King Street.

|

|

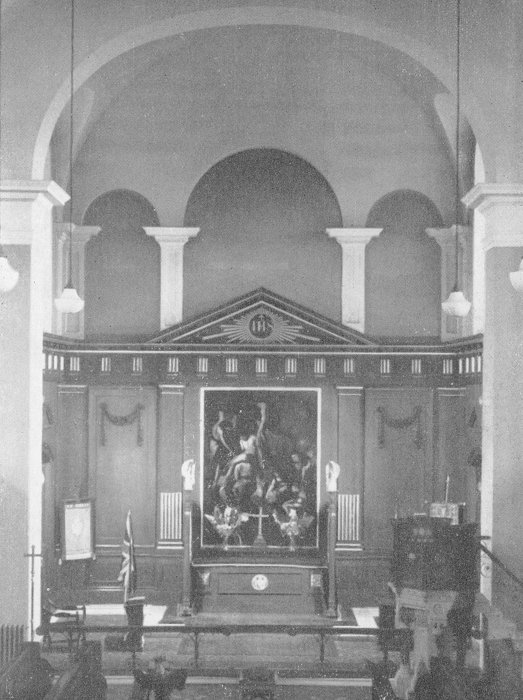

An internal view. |

Five of the trustees who were owners of

an extensive area of land known as the Cock Crofts,

stretching from Snow Hill across to Worcester Street, had

made a free gift of some 2 acres of this as a site for the

new church and burial ground and once the Act for the

building of the church had become law a start was possible.

The choice of an architect and a

builder was the first problem. It is now virtually certain

that for their builder the trustees selected a Wolverhampton

man. Roger Eykyn. He, in turn, was probably responsible for

the ultimate decision to appoint as architect William Baker

of Audlem, Cheshire.

Eykyn's father, the James Eykyn already

mentioned as trustee, was well-known in the town. His

premises were in High Green (the present Queen Square) where

he carried on a flourishing trade as an upholsterer. His

son, Roger, appears to have taken an interest in building

quite early in life and soon became an amateur architect of

the type so frequently found in England at this time.

|

|

The experience he was to gain in the

building of St. John's probably enabled him to design his

own church in Birmingham (St. Paul's) in the 1770s. This

bears a striking similarity to St. John's in many of its

details, and was almost certainly modelled on it.

Closely associated with Eykyn at this

time was the architect mentioned, William Baker, whose name

first becomes known to us in 1743, in which year he designed

the Butter Cross at Ludlow. From then onwards, he was

engaged on a number of Midland buildings and in 1749 he went

to Patshull Hall to work under the instructions of its

owner, Sir John Astley, Bt., who was then in the course of

reconstructing the house. It is at this point that Baker's

association with Wolverhampton becomes important.

Sir John Astley had about 1742 engaged

James Gibbs, Sir Christopher Wren's famous successor, and

architect of St. Martin's-in-the-fields, London (1722-6) to

redesign his house and church at Patshull, but it appears

that Gibbs was unable to complete the work there, probably

because of ill-health, and Baker took over from him.

According to Baker's own account book he was at Patshull

fairly regularly from 1749 until about 1759, so that it does

not altogether come as a surprise to find the following entry in August 1755:

July 28-Aug. 5. Paid Expens. to

Patshull & Surveying of Plans for Wolverhampton Chapel. 9s.

Several entries similar to this follow

Baker was at the stone laying ceremony in April of the

following year, and charged a further guinea for his

trouble. Between that date and the end of 1759 his accounts

show that he received about £190 as fees from one or other

of the commissioners of St. John's.

There seems very little doubt on this

evidence that Baker did in fact design the church, though we

should not dismiss entirely the possibility that Eykyn

himself drew up the plans, and that Baker acted as overseer

of the work, as he almost certainly did at Penn Church in

1765.

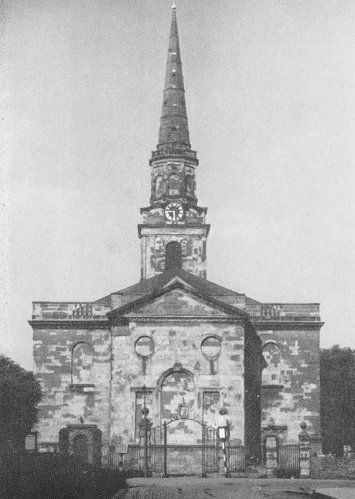

The new church was of brick, encased in

Perton freestone, which was brought from Lord Wrottesley's

estate, an excellent stone, as Richard Wilkes, the famous

Willenhall antiquary described it when he saw the building

going up. By 1758, the nave, chancel and tower had been

erected, and the interior of the church was being plastered

and fitted out. As the present spire was not at the time

intended, probably because of expense, the building must

have been almost ready far use. And then the oft recorded

tragedy occurred.

Wilkes tells us about it in an account

which the great historian of Staffordshire, Stebbing Shaw,

thought fit to include in his description of Wolverhampton

later in the century . . . . after it was covered and

plastered in 1758, when the wainscoat for the pews or seats

was all finished, and ready to be fixed a fire broke out in

the night (the workmen having left some in the steeple, and

well secured it as they imagined), which burnt it all, and

did same damage to the roof, the whole loss amounting to 7

or £8,000.

His estimate of the damage caused is an

exaggeration. Baker himself came over early in November to

Survey the Expence done, and his figure is much more

conservative, £350. 12. 6d. But this was serious enough in a

church barely completed and still in need of funds. How the

difficulty was overcome is not really known. Wilkes goes on

to tell us that the inhabitants of Wolverhampton went to the

principal towns, and gentlemen of fortune, to ask their

assistance, and says that this was so readily forthcoming

that they were able to clear the debt already outstanding on

the building fund and carry on with the work of repair. He

may, of course, be right, for there appears to be no record

of the more usual remedy of briefs being resorted to

although we certainly read of a rate of 5d. in the pound

being levied far the repairs and other uses of the church

shortly after its opening in June 1760.

Unfortunately, little or no details of

the actual opening ceremony survive. The Chapelwardens'

Accounts begin on 30th June, 1760 with the record of a

vestry meeting in the new church called St. John's and it is

made plain that notice of the meeting had been given both at

the Collegiate Church and at St. John's itself on the

previous Sunday. This may conceivably have been the first

occasion on which the building was used far warship.

The choice of wardens fell to the lot

of the vestry mentioned. Their names are recorded as William

Hilliard and Roger Eykyn, builder. Hilliard was well-known

in Wolverhampton far his efforts to reform the Grammar

School and it is pleasant to think that the builder of the

church himself was appointed to play an active part in it

during the early years of its life. He remained warden until

1763. Hilliard was succeeded, after one year in office, by

Thomas Wright, an ironmonger of Snow Hill.

As first minister for his new church,

Lard Stamford as patron, selected the Rev. Benjamin Clement,

B.A., a Dudley man, who had recently come to Wolverhampton

on his appointment as headmaster of the Grammar School. His

early career at St. John's seems to have been quite

uneventful but after the opening of the Roman Catholic Schoo,

at Sedgley Park in 1763 we find him engaged in a vigorous

campaign against papery. Many of his printed sermons testify

to his feelings on the subject. He remained minister of St.

John's until his death in 1768, though he became a hardy

pluralist and held the living of Braunton, Devonshire, at

the same time.

It is odd, perhaps, that the only other

official of whom anything is known during these first few

years is the dog-whipper, that important subordinate of the

wardens, whose duty it was to expel from the church such

dogs as did not behave well. This was usually done by

gripping them about the neck with wooden tangs, several

pairs of which remain up and dawn the country. At St. John's

the office was filled by William Shaw, who was paid an

annual salary of 6s. He was still serving in this capacity

in 1778 when the wardens' accounts record the purchase of a

pr. of second-hand breeches for 'Old Shaw" at the price of

1s.

|

|

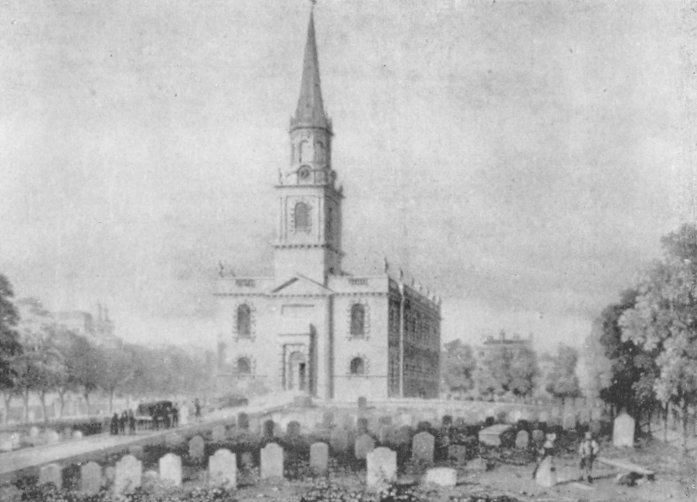

A view from around 1830. |

|

After the opening of the church,

preparations for its final completion had gone an apace. The

chapel wardens were continually finding money for same new

addition to the fabric. In August 1760, for example, the

bell had arrived, having been purchased from George Birch of

Birmingham, at a cost of £35. 1 .8, and brought to

Wolverhampton far a further 15/-. As work was still

continuing on the spire, temporary arrangements had to be

made to hang the bell in the lower part of the tower, and a

special floor was constructed far this purpose. It now

transpires that this bell, cast in 1706, belonged at one

time to St. Martin's Parish Church, in the Bull Ring,

Birmingham, and the inscription (of which there is a

facsimile in the west parch of St. John's) has the names of

an early 18th century Rector of Birmingham, William Daggett

and his two wardens. Perhaps the ring of twelve musical

Bells, mentioned by Hutton in his History of Birmingham

replaced the one sold in 1760.

The next acquisition of which anything

is known was the magnificent Communion Plate, consisting of

the silver flagon, two chalices and two plates, as the

Benefactions board has it. It was given by Samuel

Whitehouse, who was one of the original trustees of the

church. It is almost unequalled in this part of

Staffordshire. An interesting entry in the wardens' accounts

on 7th August 1761 relates that John Carter was paid 4s. for

horse hire to carry the Communion Plate to be engraved and

to fetch it back, but we are not told where the work was

done.

It would appear from the church records

that the famous Renatus Harris organ was not installed until

some time after the building was opened. and that during the

first two years of its history, St. John's had the use of

the little organ supplied on loan by a Mr. Abraham Adcock of

London. This instrument seems to have caused nothing but

trouble, for the wardens had to pay for substantial repairs

twice within the course of a few months and it cost them

nearly £12 to send it back to London after it had fulfilled

its purpose. One wonders if this unfortunate experience

prompted the opening of a subscription list for the Harris

Organ. The Benefactions Board states very precisely that it

was purchased by a subscription of £500, towards which Mr.

William Archer contributed Two Hundred Pounds, Anna Domini.

1762. The story of this superb instrument is told later.

For another 14 or 15 years building

operations were to continue, for the erection of the spire,

commenced after the disaster of 1758 (and presumably because

of it) was a lengthy task. It seems. therefore, all the more

commendable that during this period the wardens put in hand,

and indeed completed, the laying out of the churchyard, with

its walks and avenues, in preparation for the planting of

the lime trees a few years later. The brick wall surrounding

this large 2 acre site was also finished, and an order

placed with Mr. Hilliard and Co." (probably the Mr. Hilliard

who was elected warden in 1760 with Roger Eykyn), for Iron

Gates at the East End of the Chapel Yard Wall. The pair of

wrought iron gates now displayed in the Wolverhampton Art

Gallery are probably the ones Hilliard supplied. If so, it

is of interest to read that his account for them came to £10

. 1 . 9½d.: gates of similar design were placed at the

opposite end of the churchyard in 1775. The report of the

Victorian architect, Drayton Wyatt, who restored St. John's

in 1869, speaks well of this ornamental ironwork: it urges

that the gates should be restored, for they are very good

specimens of the art, and coeval with the church itself,

high praise indeed from one who was a pupil of Sir Gilbert

Scott and himself an ardent Gothicist.

Apart from all this we are fortunate in

knowing pretty well what the interior of the church looked

like during this first phase of its history, and the

opportunity will be taken at this stage to say a few wards

about this. Instead of the low, open-ended pews

which now fill the nave and aisles, there was the quite

common arrangement of enclosed boxes, each with its door and

having its number displayed in a prominent place on the

outside. Along the tops of the pews at intervals, were

wooden candlestick holders, for there was no gas lighting in

the church until well into the 19th century, and the

wardens' accounts contain references to the purchase of a

dozen-pounds " of candles at 5¼d. a pound, and of

candlesticks at 3d. each. Lighting was not a particularly

serious problem at first because of the holding of the

services only during the hours of daylight. Evening prayer

was usually said at about 3.30 p.m., after which the church

was closed for the day.

The pulpit was similar to many of the

3-deckers, still to be seen up and dawn the country. The

minister's entry and exit were controlled by a door, and

above him was the sounding board, a device which enabled his

voice to carry to the more distant parts of the building.

This was later ornamented by a dove, probably in the manner

of the pulpit of St. Swithin's, Worcester and must have been

one of the more delightful features of the church.

There was, of course, no stained glass

in any of the windows, so that the interior was almost

certainly much lighter than it is at present, especially as

the walls were as yet unpainted. The first attempt at

decoration in fact appears to have been left until 1787 when

the wardens were authorised to have the inside walls painted

with oil colours of a light colour and also the pillars:

They had previously been whitewashed.

Several additions to the church had

however been made before the date of this improvement and

among them were some of the more familiar features of the

present interior, including the magnificent coat of Royal

Arms, now hung on the front of the west gallery. These were

set up in 1778 or 1779 at a cost of £9. 9 . 0d., no small

sum of money at that period. Their authorship is uncertain

though it is highly probable that William Ellam who executed

the commandments at the same time, had a hand in them.

During the course of the following

year, 1780, the wardens were given authority to article with

Mr. Josh. Barney jun'r. to paint and complete a new altar

piece for the east end of the church. The result of this

commission was the purported copy of Rubens' "Descent from

the Cross" which today forms part of the reredos of the

chancel altar.

Barney came of a Wolverhampton family

and had himself been born in the town in 1751. When he was

16. he was sent to study under Zucchi and Angelica Kauffman,

but he eventually took up an appointment as drawing master

at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. This post he held

for 27 years and must have gained considerable distinction

in it, for we find him as painter of fruit and flowers to

King George III and as an exhibitor at the Royal Academy

from 1786 onwards. Ultimately he settled in Wolverhampton

again, to become a decorator of the japanned trays for which

the town became famous towards the end of the 18th century.

According to Pearson and Rollason's Trade Directory of 1781,

he had a house in the old Horse Fair, now part of Wulfruna

Street. His fee to St. John 's was £50. This

was paid in April 1782 so it is probable that the work took

about 18 months to complete. As proof of the esteem in which

the painting was held, another entry in the wardens'

accounts, this time in August 1806, is interesting:

‘. . a Curtain shall be put up to the

window on the South side of the communion place to prevent

the sun damaging the altar piece.’

It is unfortunate that we have no view

of the interior of the church as it was after these many

additions had been made, for it must have appeared very

different from the rather bleak interior seen by Richard

Wilkes before the fire. Few chapels of ease, for that is the

status St. John's enjoyed, apropos of the Collegiate

Church-could have claimed to be more handsomely appointed.

This fact does indeed prompt us to

consider the people the new church had come to serve during

the first 40 years or so of its history, for many of them

played an important part in beautifying and adorning the

fabric and in serving one or other of the church's offices

such as warden, beadle or clerk.

When St. John's was opened for worship

in 1760 it stood in comparative isolation. The square which

now surrounds it was not yet begun, nor had George Street or

Church Street been built up. Temple Street (Grey Pea Walk)

was, as its old name implies, a mere footpath from one side

of the town to another, whilst the west side of Snow Hill

had but a few houses on the edge of the great fields which

stretched from Worcester Street to the main Dudley Road and

were known as the "Cock Closes." And yet during the 20 years

or so which saw the completion of the church, changes of

unparalleled consequence for the town took place. The first

directory of Wolverhampton, published by Sketchley and Adams

in 1770, gives us an idea of how firmly industry had taken

root in some quarters of the town by that date, and in

particular, so far as the history of St. John's is

concerned-in Snow Hill. No longer did the traveller to

Dudley look across open fields in the direction of Worcester

Street and Brickhill Lane; houses, workshops, and business

premises of many kinds were beginning to crowd the one side

of Snow Hill, and already by 1770 we read of buckle-makers,

lock-makers. toy-makers and other men of small trades

established there. On the other side of the hill, the old

Hall, long the ancestral home of the Levesons, had been

converted for use as a japanning factory by Taylor and

James, and within a few years under the direction of William

and Obadiah Ryton, was to become one of the most famous

centres of the industry in the Midlands.

No less than 68 different trades

associated with iron, tinplate, or brass are listed by

Sketchley and Adams as being in or near to the centre of the

town. Wolverhampton was growing rapidly and St. John's was

in a part of it which was to be extensively developed.

Pitt's drawing of the town, published in 1796, gives us an

idea of the way in which new building was changing the

scene. Whole streets of houses and workshops in the Dudley

Road, Snow Hill area are seen and the industrial development

on the south and south-west sides of the present square is

astounding.

It is not surprising then when we look

into the church's own records for the period to find that

many of the people active in the life of St. John 's were

also closely connected with the new industrial growth of the

town. The list of wardens from 1760 to 1790 provides us with

at least 16 names of those engaged in one or other of the

many branches of the metal trades. Among them we discover a

Steel Tobacco Box Maker, 2 Buckle Makers, a Toy Maker, a

File Maker, a Brass Founder, a Pistol Tinder Box Maker, and

a Hinge Maker. The town of small trades is thus

appropriately represented, and after the beginning of the

new century names such as William Ryton and Richard Farmer,

famous in the Midland japanning trade, vivify the annals of

the church on almost every page.

So much, then, for the more general

history of St. John's during the latter part of the 18th

century. It had been one of more or less constant change and

development; so much so, in fact, that when we consider its

history in the first half of the succeeding century, it

tends to disappoint us. For the greater part it was a period

of consolidation. Few material changes are recorded, and the

accounts and minute books are devoid of the fascinating

information we find earlier on. There is a good deal of evidence, however, that the church

continued to flourish.

Towards the end of the Napoleonic wars,

the Rev. Joseph Reed had been appointed Minister of St.

John's. He was an energetic man, interested in education and

cultural activities in the town. No doubt it was due to his

influence that the church at this time provided a weekly

Evening Lecture, paid for by subscription. Reed's

intellectual talents also found an outlet in the running of

a Seminary in his house in Dudley Road, where French,

Drawing, English, Latin, Greek and everything else, except

Science, was taught. Like his predecessor, the Rev. Benjamin

Clement, he held St. John's in plurality, being curate of

Bobbington; he was also chaplain to the Earl of Stamford,

his patron.

|

|

|

|

|

An

internal view. |

|

A

view from the east. |

|

|

The records of the church for the

period between, say 1820 and the beginning of Queen

Victoria's reign in 1837 are in the main unfruitful, though

it is pleasant to find associated with St. John's at this

time such names as Robert Noyes, whose delightful water

colours of old Wolverhampton are one of our most valuable

sources of local history, and George Cope, the wine and

spirit merchant, of Lich Gates. His famous shop still

remains, much altered, as the only ancient building in Queen

Square. We should not forget, moreover, that St. John's

Schools in Cleveland Street had their origin during these

years, and formed one of the largest of the National Schools

in the town. The buildings were opened for use in 1832.

Towards the end of the period, we find

the trustees of the church occupied by a problem which had

beset generations of English churchgoers, namely that of pew

rents. By the Act of Parliament under which St. John's had

been founded in 1755, the greater part of the Minister's

stipend derived from rents, fixed and set upon the pews or

seats. These were not to exceed £200 in any one year, nor to

be less than £130. Out of them the Minister was to pay the

Clerk his annual salary of £10. This arrangement was not a

satisfactory one any longer. The trustees were insistent

that they should have power to vary the pew rents and

reimburse the Minister accordingly. The proposed change did,

however necessitate the promotion of another bill in

Parliament, and it was not until March 1840 that this became

law and the trustees could carry their plans into operation.

The whole system of rents was

accordingly revised. A list which appears in the Minute Book

in April 1840 is of more than local interest, providing as

it does an example of the manner in which Victorian

churchgoers were so frequently assessed. The seats in the

middle aisle of the church attracted the highest rents; the

figure varies from 14/- to 5/- for each kneeling. Then come

the two side aisles where the amount decreases as the seats

get further away from the centre of the church, numbers

22-24, for example, are charged at a mere 4/- each kneeling.

The first three rows of the galleries were considered

important enough to be charged at approximately the same

rate as the aisles and even the three small seats adjoining

the organ cost their occupants 4/- a kneeling.

An informative little note below these

entries, in a different hand-tells us that the pews in the

middle aisle are calculated at 6 kneelings, the large pews

at 8 kneelings, and the small pews at 5 kneelings. Those by

the pillars accommodated only 2 people.

All this may sound rather unrealistic,

especially when we consider the interior of the church

today, but we should remember that in 1840 St. John's still

had its Georgian Boxes which were much higher than the

present open-ended pews, and were made secure by doors

latched in no uncertain manner. A pew was, indeed, a

stronghold, the privilege of which could only be guaranteed

by the timely discharge of its rent! At any rate, the new

Act of Parliament appears to have served its purpose, for we

hear no more of this usually controversial subject for some

time.

Perhaps the promise of St. John's

becoming a parish church, with its own vicar, was sufficient

to provide a topic for discussion among its people during

the middle part of the century. After the suppression of the

ancient Wolverhampton Deanery by the Wolverhampton Church

Act of 1847, St. John's was constituted a parish-and for the

first time for nearly 90 years was not dependent on the

Collegiate Church.

As one would expect, in an age when the

building and reconstruction of churches up and down the

country was occupying an extremely prominent place in men's

minds, the task of restoring the fabric of St. John's was

another subject which was now to loom very large is, in

fact, true to say that between 1854 and 1881, renovation and

repair of one kind or another went on almost continuously

and right in the middle of the period came the first major

restoration, under the London architect, Drayton Wyatt. This

was an event of great importance, and we may consider it in

some detail.

Wyatt was a pupil of the famous Gilbert

Scott, the arch Gothicist of Victorian England, whose mark

has been left on over 700 churches, restored according to

his somewhat hard and fast rules is, therefore, the more

amazing that a person whom we can only assume followed at

this time pretty closely in his master's footsteps should be

let loose on a building so uncompromisingly Classical in

design as St. John's. The result of Wyatt's first visit,

however, was far more happy than might have been expected.

He opens his Report (in 1868) by saying

that the Classical Style of the Church is not now prevalent,

but that it would not be prudent to alter the general

character of the building in any way. The exterior

stonework, he reports, has perished, though it is not

dangerous, and he does not suggest any serious external

restoration at all. This is perhaps very fortunate, as it is

doubtful indeed whether Wyatt was competent to restore a

church built in the Gibbs fashion!

Internally, however, there was room for

much improvement. He suggests the lowering of all the pews

to a height of 3 feet, and the use of the old panelling thus

left over in "rebuilding them into modern pews." Further,

the floors should be tiled and the glazed doors at the west

entrance of the church should "be moved further west and a

glazed fanlight fitted above them." To give more efficient

lighting, he recommends the new sunlight appliances in the

nave, and gas standards or brackets under the galleries.

There was little else that troubled

him, though his strictures on the 18th century pulpit are

worth noting. "Anything more unsightly or inconvenient than

the present Desk would be difficult to conceive"; obviously

the traditional arrangement of the "three-decker" was not to

his Gothic taste and though the site of the pulpit was not

altered from South to North as Wyatt went on to suggest, the

present rather conventional pulpit with its massive stone

base is the direct outcome of his report.

His advice was accepted almost

unreservedly, and in March 1869, a Wolverhampton firm, G. &

F. Higham of Castle Street, were authorised to begin the

work. The church was closed until the following October.

Meanwhile, the subscription list was put out and it is of

interest to note that the patron of St. John's, the Earl of

Stamford, was still conscious enough of his position to open

it with a donation of £100. A printed copy of the list hangs

in the South porch; it leaves little doubt as to the

response to the wardens' appeal for funds.

The re-opening was marked by a dinner

in St. John's Schools, provided by Mr. A. R. Britton of the

Star and Garter. About 100 people were present, including

the architect himself, the Dean of Lichfield, and the Mayor

of Wolverhampton. It is a testimony to Victorian

thoroughness that the visiting clergy on this occasion were

first assembled at Messrs. W. & H. Bates' Warehouse, before

being allowed to proceed to the dinner. From the reports

given in the local press of the re-opening, it is clear that

it was considered a major event in the town that its second

oldest church had been restored so extensively.

There were, however, matters other than

these with which the people of St. John's had to concern

themselves at this period. One, in particular, is worthy of

note. The church had, since about 1840, been faced with the

problem of a parish that was rapidly outgrowing its

strength. The area east of the Dudley Road was beginning to

develop on an extensive scale. New houses and new streets

were being built in the manner and on a scale so typical of

middle-class Victorian prosperity in the manufacturing

towns. This meant an ever-increasing burden on the church,

especially after St. John's became a parish church in 1849

and it was clear that very soon provision would have to be

made for new church accommodation in that quarter of

Wolverhampton.

The answer came in the form of a

mission church, attached to St. John's, and staffed by its

clergy. In the Minute Book early in 1865 there appears the

following memorandum:

In February 1865 the Mission Church and

Schools of All Saints in Steelhouse Lane were opened at a

cost of £300 raised by voluntary contributions aided by a

grant of £80 from the Diocesan Church Building Society and

£10 from the National Society. (The ultimate cost was £400,

beside £40 for the organ.).

There is little doubt that the Vicar of

St. John's, the Rev. Henry Hampton, had been largely

instrumental in the foundation of this new church, and the

records show that he played an extremely active part in its

history until his death in 1880. Only a few months prior to

this event, the fabric of the present All Saints' Church was

consecrated, and in July 1881 a new parish was constituted.

Henry Hampton was succeeded by the Rev.

R. B. Forrester. He remained until 1902 and was in turn

succeeded by the Rev. Robert Allen, whose incumbency brings

us down to modern times. During the 40 or so years

represented by the combined office of the two vicars, a

great deal of the more recent work evident in the interior

of the church was executed. In 1899, for example, the oak

panelling in the chancel was installed and a more fitting

background for Barney's picture of "The Descent from the

Cross" was thus provided. Six years later, the Church was

fitted with electric light. In 1907, the 18th century

wrought iron gates in the churchyard were replaced by the

present ones, and it is pleasant to be able to record that

these were manufactured in Wolverhampton, for they are

admirable specimens of local ornamental ironwork. One pair

of the original gates was placed in the town Art Gallery.

It was during this period also that

some of the finest stained glass which the church' possesses

was given. Three of the windows, in particular are of a high

order of craftsmanship, notably the one in the Kilby chapel,

in memory of Florence May Allen, and two in the north aisle

proper-one in memory of the Higham family, and the other to

the memory of Job Evans. The latter was executed by the

Camms of Smethwick, the other two by Archibald Davies of the

Bromsgrove Guild.

The Rev. Robert Allen left St. John's

to become Vicar of Bradley, near Stafford in 1924, and he

was succeeded by the Rev. Henry Samuel, who remained until

the appointment of the Rev. Joseph Hartill in 1931. In this

latest period of the church's history, two very important

additions to the fabric have been made; they are the chancel

altar, designed by J. A. Swann in 1929: and the splendid

Kilby Memorial Chapel at the end of the north aisle. This

has been fitted up to commemorate Thomas Arthur Kilby

one-time churchwarden of St. John's and headmaster of the

church day school. It is appropriate to mention here that

the altar reredos, made from the desk used by Mr. Kilby in

his school, the altar itself, the communion rails and the

credence table, are all the work of the Rev. Joseph Hartill.

A plaque, handsomely lettered in contemporary style, records

this. most fitting memorial.

The purchase of the Renatus Harris

Organ and its installation in St. John's church have already

been mentioned, but the history of this splendid instrument

is of such interest that it merits fuller discussion.

It is now generally accepted that the

organ was acquired for the town of Wolverhampton from the

widow of John Byfield, an 18th century organ builder of

considerable repute and skill, and probably son-in-law of

John Harris, his partner. Harris himself was son of the

famous Renatus Harris, one of the two great organ builders

in England in the latter part of the 17th century. How

Byfield came by the organ is an oft-told story, but it will

bear repetition-and, perhaps, a few suggestions as to its

authenticity or otherwise.

In 1682, the ancient Temple Church, in

London-spiritual home of the two societies of the Inner and

Middle Temple was in need of an organ. There appears to have

been some dispute among the Benchers of the respective Inns

of Court as to who should, in fact, build the instrument; it

is suggested that the Inner Temple supported Renatus Harris,

whilst the Middle Temple was in favour of his great rival,

Bernard Schmidt ("Father Smith"), who had come to this

country from Germany in 1660 only a few months after the

arrival here of Harris and his father from France.

In an attempt to settle the dispute,

both Harris and Smith were permitted to set up organs in the

church, and the famous Battle of the Organs thus began. By

1684, if we may believe the rather scanty records which

exist, the instruments had been completed, and the trial

began. This was to last for four years, during which period

many eminent musicians are believed to have been engaged by

the rival contestants. It is thought that Henry Purcell,

John Blow, and Giovanni Draghi (organist to the Queen) were

all involved in this long drawn-out struggle. New stops were

from time to time added by each builder in an attempt to

outdo his rival-but with little or no success.

Finally, in 1688, a decision was made.

It was in favour of Smith. Harris' organ was rejected and he

was asked to remove it from the church though without loss

of prestige"; he received £200 by way of compensation.

Whether, in fact, the notorious Judge Jeffreys made this

ultimate decision, as is sometimes suggested, is more than

doubtful. Much as one would like to think this romantic

story true, there does not appear to be a shred of reliable

evidence to support it. It has been suggested that Judge

Jeffreys was implicated owing to the untimely death of Lord

Guildford, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, who was appointed

by the Benchers as arbitrator in the contest.

Whatever the truth of the matter, a

part of the Renatus Harris organ was conveyed to Dublin and

installed in Christ Church Cathedral. It is possible that

the superbly carved case, with its Crown and Mitres dates

from this time: there is, unfortunately, no proof that

Grinling Gibbons was responsible for it, though it reflects

the influence of his school.

The organ remained in Dublin for just

over 60 years. In 1750, John Byfield was asked by the Dean

and Chapter to repair it, but it seems that he managed to

persuade them that a new instrument would be a better

proposition, and he took the Harris organ in exchange for

it. It was some time before an opportunity came of disposing

of this. He appears to have attempted to sell it to the

parishioners of King's Lynn, for use in St. Margaret's

Church there, but it was disdained because it was

second-hand. The famous Snetzler was, instead, invited to

build an organ for them, and part of it remains in the

church today. What King's Lynn despised, Wolverhampton was

glad to accept. Byfield was dead, when the opportunity arose

to purchase the old Harris organ for the chapel of St. John,

but his widow was apparently satisfied to part with it for

the sum of £500 and by 1762 it was set up and in use at St.

John's.

It was erected in the usual position in

the west gallery, where its wonderful case and array of gilt

pipes have ever since been objects of admiration. No

instrument more in keeping with the Classical character of

the church could have been found: it forms an almost perfect

adjunct to the west end of

the building.

There have, of course, been several

alterations to this organ since its installation, but it may

suffice here to say that the first major changes do not

appear to have been made until 1828, When George parsons of

Bloomsbury was called in, after a special meeting of the

township had been held to consider improving the organ:

parsons' report is of great interest to organ students - it

appears in full in the wardens, accounts for 1828, but

briefly what his work seems to have entailed was the

thorough cleaning of the pipes as they are completely

choaked with dust, the provision of additional notes to the

top up to five alt., and at the wish of the organist, Mr.

Rudge, the removal of the vox humana stop from the choir

organ as it is now quite useless and the substitution of an

open diapason on the pedal organ. His report ends with the

encouraging words ". . and I pledge myself it Will then be a

most complete instrument and none will excel it."

After this, there were renovations and

repairs by Tubbs of Liverpool who aspired to change the

instrument into a ‘C’ organ in 1868 and by Nicholson and

Lord of Walsall, in 1881 and on a number of occasions later

on. It may perhaps be mentioned here that at the 1881

restoration, the organ console was first brought forward in

front of the instrument, and the original door panels in the

case sealed. It was in this year that Sir Robert Steward,

organist of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, visited

Wolverhampton and poured out his eulogy on the organ at St.

John’s, commenting that it was far superior to Byfield's old

‘saw Sharpener’ which had replaced it in Dublin.

The Harris organ has, indeed, been the

more fortunate of the two instruments which figured in the

great battle of over 250 years ago, for the Temple organ

which Father Smith built was destroyed in the fire raids on

London in 1940.

|

|

Return to

Religion |

|