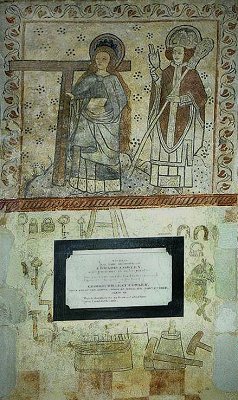

ST. LOE AND THE EARLY HISTORYOF LOCK MAKING IN WOLVERHAMPTONFrank SharmanDuring his talk to the Annual General Meeting of the History and Heritage Society, Chris Upton mentioned that there had been a chapel dedicated to St. Loe in St. Peter’s church. This was of interest because St. Loe was the patron saint of locksmiths. It occurred to me that this might be earlier evidence of the lock trade in Wolverhampton than is usually recognised. I have followed up this fascinating lead and find that, in his history of St. Peter’s (1836), the Rev. G. Oliver says, in a footnote on page 46, that the south aisle contained four chapels, Our Lady’s, St. Loe’s, St. George’s and Piper’s. Dr.Oliver is not always the most reliable of historians but there seems no reason to doubt him on this. What is more difficult to say is when the dear Doctor thought these chapels existed. The footnote occurs in a passage in which he is talking of the year 1311 but it does not seem that he is attributing this sort of date to those chapels. But Chris Upton, in his “A History of Wolverhampton (at page 27) mentions John Huntbach’s reference to the chapel of St. Loe and seems to date these references to the late medieval period, so perhaps we are talking about St Loe’s chapel being in existence before 1485. Of the four chapels Oliver mentions, those of Our Lady’s and St. George’s may be taken as self explanatory, though we may note that in its early days St. Peter’s was known as St. Mary’s, a dedication which was revived for a time, by some, in the 19th century. The reference to Piper’s is more doubtful but, of course, Piper’s Row springs to mind. Mander’s History of Wolverhampton, says that this street was named after one John Pippard, who appears in the early 15th century records as the first chaplain of the hospital founded in 1402. Mander goes on to say that “it is probably he who is responsible for the name ‘Piper’s Chapel’ in Wolverhampton church”. So that leaves us to wonder about St. Loe’s chapel. St. Loe also goes under the names of St. Eloi and St. Eligius. He lived from about 590 AD to 660 AD. His story is unusually well recorded for so early a saint. In brief, he started off his career as an apprentice to a goldsmith and became a master goldsmith but also, it seems, a general metalworker and blacksmith. From this position he became a minister to the king and was Chief Counsellor to King Dagobert. He seems to have specialised in diplomatic affairs. In later life he took holy orders and was appointed him as Bishop of Noyon-Tournai. Instead of treating this as a sinecure for his retirement he became a very active cleric, being particularly noted for his church building and also for his international concerns. He was said to have the gift of prophecy. One story attached to him is that he was asked to shoe an unruly horse which no one else could get near. He simply removed the horse’s leg and shod the hoof while the horse stood quietly by, limited in its liveliness by the need to balance on three legs. Loe then reattached the horse’s leg. It is clear from all this that St. Loe was closely associated metalworking, especially goldsmithing and blacksmithing. In Catholic iconography, he is often represented carrying a church, wrought in gold, on his hand. He became the patron saint of all metalworkers. Although other saints are also said to be the patron saint of metalworkers or of some sort of metalworkers, and St. Loe is also said to be the patron saint of things other than metalworking, there seems little doubt that in medieval times he was mostly associated with patronage of metalworkers.

This seems to me to be the best evidence we have for the early lock trade in Wolverhampton. According to J C Tildesley, in his “Locks and Lock making”, the "introduction of the lock trade into South Staffordshire took place as early as the reign of Queen Elizabeth, but it did not flourish very extensively until the end of the 17th century." His authority for this account of earlier times is not cited. It seems to me that the lock trade was well established by the time of Queen Elizabeth and the chapel of St. Loe is evidence of a much earlier date. Tildesley is on firmer ground with the Hearth Tax of 1660 when, it appears, most of the 84 hearths in Wolverhampton and 95 in Willenhall "were used by the locksmiths of those times". Dr. Plot, writing in 1686 also comments that the "greatest excellence of the blacksmith’s profession in this county lies in their making of locks for doors, wherein the artisans of Wolverhampton seem to be preferred to all others …". He treats the industry as being well established and well developed. I have always assumed that this industry arose out of the Wolverhampton blacksmiths’ providing services for the wide agricultural area that was served by its market – a market, that in wool at least, was international in its scope. Such blacksmiths would have been called upon to make, apart from the other most obvious things such as agricultural tools and equipment, the metal parts of harnesses and locks and latches and the like. And it was from here that the buckle making trade developed as did the lock making trade, the trades that were, in the 17th century and later, recognised as the leading trades of the town. It seems to me that the chapel of St. Loe in St. Peter’s church, may be taken as good evidence that lock making, as well as general metalworking was established in medieval times, certainly in the 1400s, as an important and distinctive trade. We are told that there were no guilds in Wolverhampton. This may well be the case in the formal sense of a trade guild. But we know that the Mercers had representation here and, almost certainly, their own cloth hall. The existence of this chapel indicates that, in medieval times, the lockmakers and metal workers of Wolverhampton were sufficiently well organised, and sufficiently well off, to provide a chapel for their patron saint. I have little doubt that we will never find a date at which the first lock was made in Wolverhampton. But we can, with some certainty, say that the industry was well established in the town’s earliest centuries. |