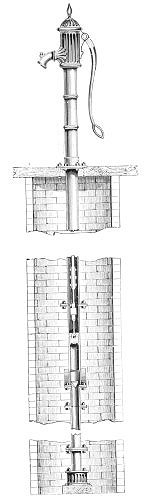

Lambeth Brass & Iron Co. advert. 1901. |

Many Black Country industries flourished in the first half of the 19th

century. There were coal mines, all kinds of iron and metalworking,

foundries, chain making, galvanising, chemical works, paint works,

japanning works, enamelling works and many more. Factories were

sometimes built next-to, and around existing houses, and often

businesses were run as small cottage industries, in workshops adjoining

houses or even inside them. Living next to a factory must have been very

unpleasant, especially as there were no clean air acts and dangerous or

poisonous waste could be left lying around to enter the water table, or

be washed around during heavy rain. Many areas had open sewers and

drains, the contents of which ran into a nearby canal, brook, stagnant

pool or open field. Toilets mainly consisted of an open receptacle, the

soil being covered over with ashes from the fire. They were often built

over old ditches or water courses and so the waste would eventually wash

into one area to form a stagnant pool.

In parts of Willenhall water was scarce because of the large number

of coal mines in the area and so it was drawn from ditches and a small

brook. The brook was frequently choked with refuse and even dead dogs.

People used to fill a bucket with water and let it stand or settle

before use. Darlaston had many stagnant pools and piles of sewage and

Wednesbury, Great Bridge and Dudley Port relied on the River Tame. Most

of Wednesbury’s surface water, including some from privies ended up in

the river. The river ran past Chance’s alkali works and at that point it

turned red from the work’s effluence. The river also ran past Bagnall’s

works at Gold’s Hill and the Patent Shaft works at Wednesbury. Both

works employed a large number of people and discharged untreated sewage

into the river.

|