|

Anglo-Saxon England The Saxons

slowly migrated into the West Midlands from

the north along the River Trent and its

tributaries. They were colonising the area

by the 6th century. A late seventh century

document for tax assessment called the

“Tribal Hidage” lists the dominant tribes in

the area and suggests that the inhabitants

were from the Pencersaetan tribe that took

its name from the River Penk. The early

Anglo-Saxon communities lived in small

villages with timber huts thatched with

straw, reeds, or heather.

The Venerable Bede, a Priest at the

Monastery of Saints Peter and Paul at

Wearmouth and Jarrow completed his

“Ecclesiastical History of the English

People” in 731. It is the primary source of

information on the early English people and

the coming of Christianity. |

|

| This is what he had to say about the

early immigrants and their territory:

Those who came over were of the three most

powerful nations of Germany - Saxons,

Angles, and Jutes. From the Jutes are

descended the people of Kent, and of the

Isle of Wight, including those in the

province of the West-Saxons who are to this

day called Jutes, seated opposite to the

Isle of Wight.

From the Saxons, that is, the country

which is now called Old Saxony, came the

East-Saxons, the South-Saxons, and the West

Saxons.

From the Angles, that is, the country

which is called Angulus, and which is said,

from that time, to have remained desert to

this day, between the provinces of the Jutes

and the Saxons, are descended the

East-Angles, the Midland-Angles, the

Mercians, all the race of the Northumbrians,

that is, of those nations that dwell on the

north side of the river Humber, and the

other nations of the Angles. |

|

|

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Due to continuous warring the

boundaries changed many times. Anglo-Saxon England was a turbulent

country with a number of competing kingdoms, always under threat

from European invaders. As the Anglo-Saxons slowly colonised the

country, seven kingdoms were established which later became known as

the “Heptarchy”. They were: East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia,

Northumbria, Sussex and Wessex

There were many squabbles between them and the last three of the

kingdoms; Mercia, Northumbria and Wessex were in a continuous state

of war.

Mercia, founded in about 500 A.D. occupied much of southern England

up to the Trent basin. The first identifiable king was Creoda, who

ruled from 586 to 593. He was succeeded by his son Wybba, who ruled

until his death in 615 and followed by Ceorl and Penda who was one

of the most powerful Mercian kings.

A major influence was the coming of Christianity in the sixth and

seventh centuries. It was brought by Irish monks to many places such

as Iona in 563 and Lindesfarne in 635.

King Penda who ruled from 632 to 654 was followed by his sons, Peada,

Wulfhere and Ethelred.

Tradition has it that King Wulfhere founded the Abbey of St. Mary at

Wolverhampton (now St. Peter’s Church) in 659 but there is no proof

of this. The diocese of Lichfield was formed when St. Chad was

appointed as bishop of the Mercians in 669 with a central church at

Lichfield.

Ethelred conquered Kent in 676 and founded the monastery at

Worcester in 679. In 685 Mercia became the supreme power when

Northumbria was invaded by the Picts. Ethelred retired in 704 to a

monastic life, to be succeeded by his nephew Cenred. His successors

were Ceolred followed by Aethelbald.King Aethelbald came to power

in 716. In his early years a hermit called Guthlac predicted that he

would have great success in the future and he tried to live up to

this by ruthlessly suppressing several of the smaller adjacent

kingdoms. He attacked Northumbria with little success but Cynewulf,

king of Wessex eventually acknowledged Aethelbald’s superiority. He

had control of most of the country and almost became the king of the

whole of England. He gave grants to many churches, created a number

of monasteries and gave alms to the poorer members of society. In

757 he was killed in battle near Burford, Oxfordshire and his cousin

Offa seized power.

Offa is probably the best known Mercian king and was the first

ruler to be called “King of the English”. To consolidate his

position he formed alliances with Northumbria and Wessex and his

daughters were married to their kings. Like his predecessor he

ruthlessly suppressed any opposition. Between 784 and 786 he built

Offa’s Dyke, a long earthwork running 149 miles along the western

boundary of Mercia to keep out the Welsh. He introduced the English

penny, which was the forerunner of modern coins. Most of the coins

carried his portrait and some carried the portrait of his wife,

Cynethryth. The coins were probably minted at Canterbury. He formed

links with the Emperor Charlemagne and visited Rome in 792 to

strengthen his links with the papacy.

Offa had a number of royal palaces, his main residence was at

Tamworth. He died in 796. His son Ecgfrith became king but

unfortunately he died a few months after Offa. |

|

An Offa penny coin. |

Cenwulf succeeded Ecgfrith and reined until 821. He died while

preparing an assault on Powys and is buried in Winchcombe Abbey. He

in turn was succeeded by his brother, Ceolwulf. In 823 Beornwulf

forcibly took control of Mercia but only ruled for two years.

In 789 Offa sent Egbert, the claimant to the Kingdom of Wessex, into

exile in Gaul. After his return in 802 he became King of Wessex and

decided to seek revenge by destroying the supremacy of Mercia. This

he duly did and defeated the Mercian army at the Battle of Ellandon

in 825. He also seized Kent and Sussex which were previously parts

of Mercia. After the defeat Mercia invaded East Anglia and King

Beornwulf was killed in battle, to be succeeded by Ludecan, who was

killed two years later. Wiglaf became the next to rule, but within a

year Egbert took over the whole of Mercia. |

In the 800s and 900s the Vikings attacked the English and French

coasts. In France they were given an area in the north of the

country that became known as Normandy (land of the north men).

By the end of 828 Egbert ruled the whole of England and from now on

rulers of Mercia would answer to a national king. The first such

ruler appointed by Egbert in 830 was the deposed Wiglaf, who was in

charge until 840. Egbert ruled until his death in 839 and was

succeeded by his son Ethelwulf who reigned until 856.

In Mercia, Beorhtwulf succeeded Wiglaf and ruled until 852, and he

in turn was followed by Burgreda who ruled until 874 when the Danes

overran Mercia. |

A coin of Ethelred II, King of Northumbria,

840 to 844. |

Early Anglo-Saxon kings were military leaders who were assisted

by their lords (thanes). The kings allotted land to the lords who

oversaw their villages. The villagers were dependant on their lord

for food and labour. The kings were advised by wise men (Witan or

Witenagemot) who formed an assembly of councillors to advise on

administration and judicial matters. The wise men included bishops

and church officials, friends or relatives of the king and local

chieftains. They also authorised taxes, grants of land and the

raising of armies.

The Kings had a number of Royal Manors throughout the kingdom and

visited them with the royal entourage. This was a little like a

modern Himalayan mountaineering expedition where everything,

including the kitchen sink is carried by porters. There is a

description of this in J. R. Green's "Conquest of England" which is

as follows: |

| We see the king's forerunners pushing ahead of the

train, arriving in haste at the spot destined for the

next halt, broaching the beer barrels, setting the

board, slaying and cooking the kine, baking the bread;

till the long company come pounding in through the muddy

roads, horsemen and spearmen, theign and noble bishop

and clerk, the string of sumpter horses, the big wagons

with the Royal hoard or the royal wardrobe, and, at

last, the heavy standard borne before the king himself.

Then follows the rough justice-court, the hasty council,

the huge banquet, the fires dying down into the darkness

of the night, till a fresh dawn wakes the forerunners to

seek a fresh encampment. |

|

|

The area occupied by the Danes in the late

800s. |

King Ethelwulf was succeeded by each of his four sons in turn.

The eldest; Ethelbald ruled until his death in 860. He married

Judith, daughter of Charles the Bald, king of the Franks. King

Ethelbert followed his brother and ruled until 866. He in turn was

followed by his younger brother Ethelred, who ruled until 871 and

followed by his youngest brother Alfred, who ruled until 899.

King Alfred, known as “Alfred the Great”, was born in 849 at Wantage

in Berkshire. Since the end of the 8th century the country had been

subjected to Viking raids which began in northern England and

eventually spread along the eastern and southern coasts.

In 865 a vast Viking army landed on the Isle of Thanet and began a

12 year invasion. By 867 the Vikings had captured York and soon

invaded East Anglia and Mercia. The only remaining independent

Anglo-Saxon Kingdom, Wessex, was attacked in 870. The Vikings were

initially defeated at the Battle of Ashdown in 871 by the Wessex

army led by Ethelred and his younger brother Alfred. The Viking

onslaughts continued and Alfred came to power in 871 after

Ethelred’s death. The Vikings led by King Guthrum captured

Chippenham in 878 and used it as a base from which to attack Wessex.

Much of the kingdom was overrun and Alfred and a few of his

followers retreated to the Somerset marshes, which is where the

story of the burned cakes originates from. Alfred re-grouped and

built a fortified base at Athelney and gathered a mobile army to

pursue gorilla tactics against the invaders. |

In 878 his army defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Edington

and besieged Chippenham until they made peace. Alfred realised that

he could not drive the Vikings out of the rest of England and so he

made an uneasy peace with them in the Treaty of Wedmore. This led to

the establishment of the Danelaw, which gave the Danes more or less

the eastern half of the country.

Alfred didn’t stop there, he organised an efficient rapid reaction

force to deal with any incursions and ensured that many of the

settlements were well-defended. He had a royal palace at Winchester

and had many fast ships built for the defence of the coastal areas.

He was patron of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was copied and

added to in 1154. This is our main source of Anglo-Saxon history

today. He died in 899 and is buried at Winchester. He is known as

“King of the English” and “Alfred the Great”. Alfred was followed by

his son Edward (known as “Edward the Elder”) who ruled from 899 to

924.

From 911 until 918 Queen Aethelflaed ruled Mercia, she was followed

by Queen Elfwynna who ruled for 12 months. Control then passed to

King Edward. |

| Queen Aethelflaed became one of the most powerful

people in England. She won many battles against the Vikings and

captured parts of Northumbria and Wales. She strengthened the

defences at Gloucester against the Vikings and developed the street

plan that survives today.

She captured the bones of St. Oswald from

the Danes and gave them to St. Oswald's

priory at Gloucester. She died at Tamworth

and was buried in St. Peter's Church,

Gloucester. |

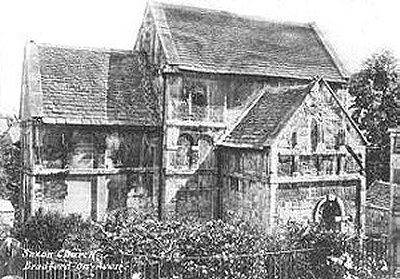

The Saxon church at Bradford-on-Avon. From an

old postcard. |

Edward continued his father’s military activities and defeated a

Viking army near Tettenhall in 910. In 924 the king of the

Strathclydwallians and the king of the Scots submitted to Edward,

who died later in the year at Farndon. His son Athelstan then became

king.

King Athelstan was an accomplished soldier who continued to oust the

Vikings. In 927-8 he captured York. In 937 at the Battle of

Brunanburh he led the army that defeated an invasion by the king of

Scotland in alliance with the Welsh and Danes from Dublin. He

encouraged people to move into towns, formed the first shires and

was an avid collector of works of art and religious relics. These

were often given away to his followers or the church, in order to

gain support. Athelstan died in 939 and was buried at Malmesbury.

His half-brother Edmund succeeded him.

King Edmund continued to suppress the Danes but only ruled for seven

years. He was murdered during a feast in 946 when he was only 25

years old. Rule passed to his brother Edred, who reigned until 955

when Edmund’s eldest son Edwy became king.

King Edwy was crowned by Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury in 956 at

Kingston-on-Thames. At the time he was only 13 years old. During a

rebellion, Mercia and Northumbria broke away and Edwy died in 959 at

the age of 16.Edwy was succeeded in 959 by his brother Edgar,

King of Mercia and the Danelaw. Edgar ruled for 14 years before

being crowned at Bath, along with his queen, Aelfthryth. He was a

good ruler who started a great monastic revival and introduced

universal coinage and laws throughout the country. He died on the

8th July, 975 at the age of 33 and was buried at Glastonbury Abbey.

His death led to a dispute between the supporters of his two sons;

Edward and Ethelred. Edward, the eldest son became king in 975. He

was murdered in 979 and replaced by his 7 year old brother Ethelred.

King Ethelred, known as “The Unready” ruled from 979 to 1013. He was

a poor ruler, which led to a great deal of unrest and hostility in

the country. He was called "The Unready" because of his inability to

govern. He was no soldier and the Vikings took advantage of this

with many raiding parties. The Vikings raided the Welsh coast and

southwest England, they attacked London and raided the east coast.

There were raids from the armies of Norway and Sweden, but the main

onslaught was from the Danes under King Swein. Ethelred attempted to

buy-off the Danes using the money levied from the Danegeld tax. He

formed a diplomatic alliance with the Duke of Normandy and later

married his daughter Emma.

In 1011 the Danish army continued to do much as it pleased. They

even attacked Canterbury and captured Archbishop Elfeah, Abbess

Leofruna, Bishop Godwin and Abbot Elfmar. In 1012 the Archbishop was

brutally murdered and King Ethelred handed over £48,000 from the

Danegeld in an attempt to pacify them. In 1013 Swein became King of

Northumbria and resistance from Wessex failed. Ethelred was

dispossessed by Sweyn and fled to Normandy.

The English lords were so disillusioned with King Ethelred that they

eagerly accepted Sweyn as their new king. Sweyn died in 1014 and

Ethelred’s son Edmund took over the throne. Edmund died in 1016 and

Sweyn’s son Canute became undisputed king. |

|

A Canute silver coin. |

Canute strengthened his position by marrying Ethelred’s widow

Emma. He also became king of Denmark and Norway. During his time

abroad, England was governed by a group of English and Danish earls.

Canute went on a pilgrimage to Rome in 1027-8 and his Christian

humility led to the story of him demonstrating that even he could

not stop the waves. He died in 1035 and is buried at Winchester.

Canute had two wives, Elfgifu and Emma. He had a son by each wife

and the two sons became rivals, initially sharing the country.

Harold Harefoot was Canute’s first son and became King of Mercia and

Northumbria. Hardicanute, the second son was king of Wessex. |

| In 1040 Harold Harefoot died and Hardicanute became king of the

whole of England. Hardicanute’s rule was very short. He died at

Lambeth in 1042 and his half-brother Edward “the Confessor” became

king. |

| King Edward was no soldier. He grew up in exile in Normandy and

on his return he was accompanied by a number of influential Normans.

At the time England was dominated by three earls; Godwin of Wessex,

Leofric of Mercia and Siward of Northumbria. Godwin became the most

important of the three when Edward married his daughter Edith in

1045. Godwin hoped that the couple would have a child which of

course would be heir to the throne. This was not to be because

Edward had taken a vow of celibacy. Edward's Norman sympathies were

viewed with suspicion by Godwin and this came to a head when the

king ordered Godwin to punish the people of Dover after a group

Normans had been involved in a brawl there.

Godwin assembled an army against Edward in 1050 but Leofric and

Siward remained loyal to the king. The army was defeated and Godwin

and his family left the country and went into exile. |

A penny from the time of Edward the Confessor. |

In 1051 Edward received his distant relative, William Duke of

Normandy as a guest. It is believed that during the visit Edward

named William as his successor.

After this defeat, Edward increased the number of his Norman

advisers, giving some of them important posts in office. There was

much hostility towards the Norman appointments and Edward lost the

loyalty of the other Earls. In 1052 Godwin arrived on the south

coast with his sons Harold and Tostig and a huge army. Edward was

unable to raise an army to oppose them and had to agree to Godwin's

terms.

Godwin was now the most powerful man in England. He forced Edward to

remove his Norman councillors, but died in 1053 and was replaced by

his son Harold, who became Edward’s chief advisor. Edward founded a

new abbey at Westminster, dedicated to St. Peter. He is said to have

named Harold as his successor on his deathbed, even though he had

earlier promised the throne to William Duke of Normandy. He may have

been manoeuvred into this by the Saxon lords. Edward died on the 5th

January, 1066 and on the following day Harold was crowned as the new

king in Westminster Abbey.King Harold would have feared the rival

claims to the throne from William Duke of Normandy and Harald

Hardrada of Norway. In his earlier years Harold had been captured in

France. Whilst still a prisoner he is said to have sworn, under

duress, that he would not accept the English throne but would

support Duke William’s claim.

He awaited the expected Norman invasion but his plans to defend the

country were thrown into disarray when his estranged brother Tostig,

Earl of Northumbria and Harald Hardrada of Norway led an invading

army from the northeast. Harold, an outstanding soldier marched

northwards with a large army and ruthlessly defeated the invading

forces. In the meantime William and his invading army arrived in

Sussex and Harold marched southwards to defend the country. Harold

and his 7,000 strong army were at a great disadvantage because they

were suffering from the exertions of their previous battle and the

240 mile long march to the south. The Anglo-Saxon era ended when

Harold was defeated near Hastings and killed during the battle.

William became the first Norman king and was crowned in London on

Christmas day 1066.

Anglo-Saxon influence is still all around us today. Not only did

they give us the name of our country but also the basis of our

language. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|

|