| As 2014 is the centenary of the beginning of the First

World War, I decided to write the following article which

concentrates on the happenings at home, rather than the

carnage abroad. It was a time of shortages and hardship for

many, and sadly, not 'the war to end all wars', as it was

known. Life in the Pre-War Era

For many working class families, life

was hard in the early part of the twentieth century, and

expectations were low. People worked long hours for low

wages, and lived in poor and overcrowded housing. Skilled

men could earn up to thirty shillings a week, and unskilled

men could expect to earn no more than twenty shillings a

week. Trades unions were becoming increasingly militant, and

strikes happened frequently. In 1913 a strike of engineering

workers lasted over two months, in an attempt to raise the

minimum wage for unskilled workers to twenty three shillings

a week. There were also strikes on the railways, and in the

coal mines, not forgetting the great unrest at Wednesbury

when the tube makers downed-tools.

Food was expensive, so much so that

some families spent sixty percent of their income on it, and

malnutrition amongst children became commonplace. Due to the

harder and more stressful living conditions, and the lack of

modern medical care, life expectancy was much shorter than

today, being around fifty years for men, and fifty four

years for women.

The turn of the twentieth century saw

the dawn of the welfare state, but only in a modest way. In

1909 the first old age pensions were paid to people over the

age of 70. They were entitled to five shillings a week. Two

years later the 1911 National Insurance Act was passed to

provide sickness and unemployment benefit for people. The

scheme was compulsory for all wage earners between the ages

of sixteen and seventy. They had to contribute four pence a

week to the scheme, which was supplemented by an additional

three pence from the employer, and two pence from the state.

In return, workers received free medical attention and

medicine, and were paid 10 shillings a week for the first 13

weeks, and 5 shillings a week for the next 13 weeks.

Unemployment benefit consisted of seven shillings a week,

beginning after the first week of unemployment, and lasting

for fifteen weeks in any single year. It was paid at labour

exchanges, which first appeared in 1910.

For many years Britain had been the

dominant economic power in Europe, but by 1914 Britain was

being outperformed by Germany, which had previously been an

important customer for many of our largest industries. As

Germany’s industries flourished, British exports suffered,

and some industries began to decline. |

Old Wolverhampton - oblivious to what lay

ahead. From an old postcard.

|

Causes of the War

For some years imperialism had grown in

most of the major European countries, which meant that at

some time, the outbreak war was almost inevitable. It

officially began on 28th July, 1914 with the assassination

of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the throne

of Austria-Hungary, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of

Hohenberg, who were shot dead in Sarajevo, by Gavrilo

Princip, one of a group of six Bosnian Serb assassins. After

the assassination, Austria-Hungary delivered an ultimatum to

the Kingdom of Serbia and prepared to invade. At the time

there were two groups of allies in Europe: The Allied Forces

consisting of France, United Kingdom, and Russia; and The

Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Britain had a treaty with Belgium, and

so declared war with Germany when the German army invaded

Belgium and Luxembourg, on its way to France. Soon all the

major European powers were involved in the war, which within

a few years, also involved many other countries throughout

the world.

When Britain declared war on 4th

August, 1914, celebrations were held throughout the country.

Most people believed it would be a quick and simple affair

that would be over by Christmas. Patriotism was high, and

large numbers of men rushed to join the forces to answer the

call to arms. The government wanted 100,000 volunteers and

began a large recruitment campaign which bombarded the

public with posters. This was so successful that within a

month 750,000 people had volunteered.

Sadly it was not to be a quick affair.

As the German troops entered France, the French and British

troops moved northwards to meet them, and the massive armies

dug-in, starting the terrible trench warfare which would

last for four years.

|

|

Wolverhampton in 1914, that Fateful Year

June 1914 was hot and dry, war seemed

far away. On 25th July an article in the Express & Star

stated that Britain and France were not interested in the

problems in Europe, and were appealing for moderation.

Within a few days the headlines changed, and people began to

realise the seriousness of the situation. On 2nd August the

headlines changed to ‘Germany declares war against Russia’.

It was stated the next day that Britain’s only involvement

would be naval and that troops would not be used, but two

days later, after the declaration of war, the main headline

was ‘England at war’.

All German subjects had to immediately

report to the Chief Constable’s office in the Town Hall, as

can be seen on the poster opposite, and

panic buying began in the shops, leading to many price

rises.

By the second week in August, volunteers were sought to

take part in the war. |

|

|

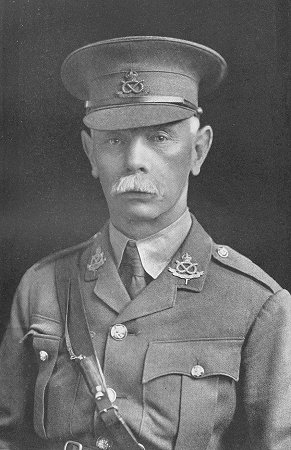

As part of

Lord Kitchener’s call to arms, Hon. Colonel T. E. Hickman

(later Brigadier-general)formed a new

battalion of volunteers to go into service with the South

Staffordshire Regiment. Participants had to be male,

between 19 and 30 years of age, and were asked to bring

another possible volunteer with them.

Lord Kitchener’s

appeal using the slogan ‘Your King and Country needs you’

led to many volunteers. One hundred thousand men were needed

immediately, to go to the front for a war that would be over

by Christmas. Even so, they had to enlist for three years,

and for the duration of the war. Men who didn’t enlist were

under a lot of pressure to do so, and those who enlisted had

no idea what they were letting themselves in for.

In August, Parliament Passed the

Defence of the Realm Act which gave the government a range

of new powers to prevent anyone assisting or communicating

with the enemy. The press was censored, to keep-up people’s

morale, and plans were made to ensure that scarce resources

were correctly used.

|

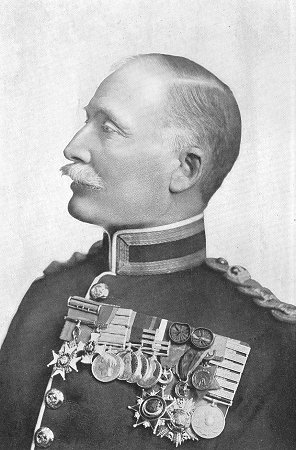

Brigadier-General T. E. Hickman, C.B.,

D.S.O., M.P. |

|

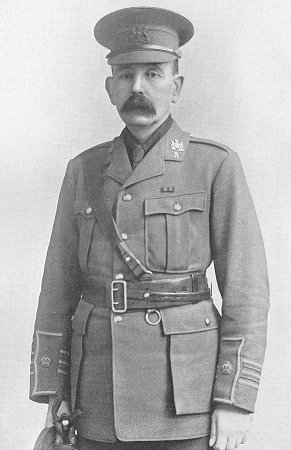

Major T. E. Lowe of the South

Staffordshire Regiment. |

|

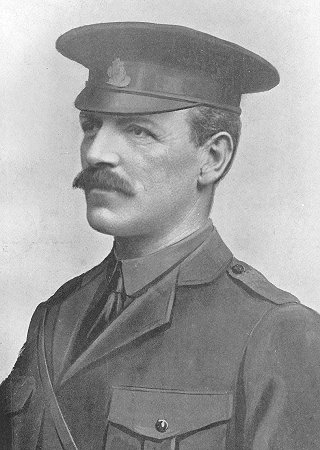

Lieut.-Col. H. H. C. Dent of the 3rd

North Midland Field Ambulance. |

|

The Admiralty and the Army Council were

given powers to take-over any factory or workshop for the

production of arms, ammunition, or products for the

war-effort. Within twelve months the shortage of munitions

led to the government setting-up its own arms factories, and

eventually taking over the vitally important coal industry.

On 5th October a civic farewell was

given at St. Peter’s Church for the 6th Battalion of the

South Staffordshire Regiment as it left for war. During the

next twelve months the battalion would sustain heavy

losses.

Much pressure was put on anyone

considered to be a potential recruit. It was impossible to

escape from the recruitment drive.

|

Major W. Pearson, Regular Army and

Special Reserve Recruiting Officer. |

|

F. Carr, Acting Commandant,

Wolverhampton Rifle Corps. |

| By the end of the year The Wolverhampton and District

Recruiting Committee had been formed, and recruiting techniques were

developed.

The committee, which consisted of teachers,

clergymen, political agents, and members of various

societies, visited every man between the age of 18 and 40 to

explain the necessity of going to war, and to encourage

enlistment.

Lady committee members visited men’s wives while

they were at work to stress that their husbands should

join-up. A man and a woman would then call on the family in

the evening to try and persuade the man to enlist. Talks were given at factories during the lunch

hour, and everything was done to assist the recruitment

drive. Skilled recruits received 9s.11d. per week, unskilled

recruits received 8s.9d. per week, with a separation

allowance for married men of 12s.6d., plus 2s.6d. for each

child.

The committee's duties included assisting local regiments

to obtain recruits, and looking after them until they moved

into barracks, or went to war. |

|

Midland Evening News, 1st September,

1914. |

Anyone involved with any of the local political parties

was asked to assist in canvassing, and the name and address

of every single man between the ages of 18 and 40 was

obtained, along with the details of every married man that

was capable of joining-up.

The committee also recorded the name of every man who had

military experience. When necessary the committee would

house, clothe, equip, look after training, and feed

recruits. Every shopkeeper was invited to display a

recruitment poster in their shop window, which could be

obtained free of charge from the committee. Posters were

also put on lamp posts, which gave the address of the

recruiting office.

Marches of scouts, girl guides and men in khaki uniforms

were organised, and three or four men in khaki uniforms were

stationed in the following streets each evening, to persuade

likely recruits to enlist:

Darlington Street, Victoria Street, Dudley Street,

Lichfield Street, Tettenhall Road, Queen Square, Worcester

Street, Snow Hill, Five Ways, Willenhall market place,

Darlaston market place, Bilston market place, and Brierley

Hill market place.

Open air meetings were held, and cinemas displayed an

army recruitment film. Clergymen were asked to mention the

need for recruits during church services, and prizes were

given to those who brought-in the largest number of

recruits.

Roll of honour cards were displayed on the houses of

those enlisted, some of whom had to wait a short while

before joining the forces. During that time they joined

route marches and assisted in the recruitment campaign. |

|

The recruiting drive continued apace.

Between December 1914 and the end of January 1915 there were

1,500 local volunteers, but still more were needed.

The

names of volunteers were displayed in local newspapers to

add even more pressure to potential recruits. In February

there was a mass recruiting meeting, and a torchlight

procession, and in May a special recruiting week.

Although

around 12,000 locals had been recruited, it was still not

enough. The futility of the stand-off between the vast

armies meant that large numbers of people were killed or

wounded, and enormous numbers of men were needed at the

front.

In the autumn of 1915 Lord Derby headed a campaign

which resulted in around 300,000 new recruits, but it was

still not enough to meet the needs of the army. In January

1916 the prime minister, Herbert Asquith, introduced

conscription for all single men aged between eighteen and

forty, which was seen as the only way to get all of the

troops that were needed. |

|

By 1915 people began to realise that

some skilled men were still needed at home. All the local

factories worked flat-out producing vital war work and

armaments for the armed forces, but initially suffered

because of the shortage of skilled men. The factories could

not operate without them and so applications were invited

for the reservation of skilled men. For the first time,

women were allowed to work in some of the more physically

demanding factory jobs which had previously been considered

to be only suitable for men. Women also kept many of the

essential services in operation including trams, the

railways, and our farms. They also worked in munitions

factories.

The vast range of Wolverhampton-made products for

military use included the following: The Sunbeam Motor Car

Company Limited produced military staff cars, ambulances,

aircraft, and aero engines. Clyno produced machine gun

carriers, ammunition carriers, and aero engines. A.J.S.

built military motorcycles, machine gun carriers, ammunition

carriers and light ambulances. Guy Motors built 30 cwt.

military lorries, aero engines, tank engines, and depth

charge firing mechanisms. Star produced aero engines,

ambulances, vehicles for use as Marconi portable wireless

stations, 50 cwt military lorries, aircraft wings, and parts

for mines. Villiers produced ammunition, including shell

fuses. Hobsons made carburettors for aero engines.

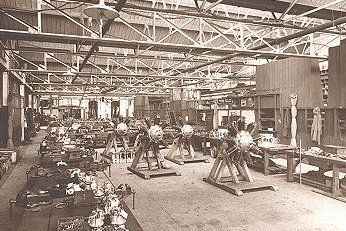

|

|

|

Clyno machine gun carriers at the

front. |

|

Dragonfly aero engines in production

at Clyno. |

|

In 1915 the Germans declared an

official naval blockade of Britain, and threatened to sink

any ships sailing into British ports. The Americans

immediately objected because many of their cargo ships

sailed here, and the blockade was cancelled. Two years later

it was reinstated, which caused the Americans to enter the

war.

The blockade by the German U-boats led

to food shortages, rising prices, and long queues at the

shops. Both sugar and wheat were in short supply. Due to the

shortage of wheat, the Ministry of Supply recommended that

20lb. of potatoes should be added to every 280lb. sack of

flour.

Zeppelin Raids

In 1916 there were Zeppelin Raids over

parts of the Black Country including Tipton, Bradley,

Wednesbury, and Walsall.

|

|

From the Express & Star, Wednesday 2nd

February, 1916:

AIR RAID DEATH ROLL

54 KILLED AND 67 INJURED BY ZEPPELIN

BOMBS

LARGEST AREA YET COVERED BY ENEMY

ATTACKS

Press Bureau, 6 p.m. Tuesday night.

The War Office issues the following publication:

The air raid of last night was

attempted on an extensive scale, but it appears that the

raiders were hampered by thick mist. After crossing the

coast the Zeppelins steered various courses, and dropped

bombs at several towns, and in rural districts, in:

Derbyshire, Leicestershire,

Lincolnshire, Staffordshire.

Some damage to property was caused. No

accurate reports were received until a very late hour. The

casualties notified up to the time of issuing this statement

amount to:

Killed --------------------- 54

Injured -------------------- 67

Further reports of Monday night’s air

raid show that the enemy’s air attack covered a larger area

than on any previous occasion. Bombs were dropped in:

Derbyshire, Leicestershire,

Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Staffordshire.

The number of bombs being estimated at

220. Except in one part of Staffordshire the material damage

was not considerable, and in no case was any military damage

caused.

No further casualties have been

reported, and the figures remain as 54 killed, 67 injured.

|

|

| At Tipton, during the frosty and foggy

night of 31st January, around eight o’clock in the evening,

three bombs were dropped on Waterloo Street and Union

Street, where two houses were destroyed and a gas main set

alight. Fourteen people were killed, five men, five women,

and four children. The airship then flew over Bloomfield

Road and Barnfield Road, dropping three incendiary bombs on

the way. |

|

At Bradley bombs were dropped over the

canal where a young courting couple had gone for a stroll.

One of the bombs exploded close to them, killing William

Fellows outright. His partner Maud Fellows (not related to

William) was mortally wounded and died just over a week

later at the Wolverhampton and Staffordshire General

Hospital. Maud, who was 24 years old worked in a Bilston

butcher’s shop and lived at 45 Daisy Street, Bradley.

William, aged 23, worked as a stoker and lived in Castle

Street, Coseley.

In Wednesbury bombs were dropped around

King Street and on Russell’s Crown Tube Works that stood

between the High Bullen and King Street, setting

the huge factory alight. Its burnt-out shell remained until the

1960s. In King Street one of the houses was completely

destroyed, killing the four occupants, who were Joseph Smith

and his three children. Joseph’s wife survived because she

left the house to investigate the cause of a loud noise,

which had been the bombs falling on the factory. Luckily the

explosions had fractured a gas main, cutting off the street

lights, which plunged the town centre into darkness.

In Walsall a bomb fell on Wednesbury

Road Congregational Church, badly damaging the main part of

the building. Unfortunately a passer-by, Mr. Thomas

Merrylees was instantly killed by a piece of flying masonry.

A short time later an incendiary bomb fell on the grounds of

the General Hospital and was quickly extinguished by a

passing policeman. |

Early in February 1916 Beatties

advertised blackout materials. |

|

Several other bombs were dropped

including one that fell on Bradford Place, killing two

people, and injuring several others, including Walsall’s

Lady Mayoress, 55 years old Mary Julia Slater, who died from

her injuries, three weeks later in the local hospital.

The Later War Years

On 1st July, 1916 the 4th Battalion of

the Staffordshire Volunteer Regiment was formed. |

| In February 1918, the continuing

shortages led to the introduction of food rationing. The

weekly ration for each person included 15 oz of meat, 5 oz

of bacon, and 4 oz of butter or margarine. |

Even horses were rationed. Horse owners had to keep a

record of the horses in their possession, the quantity of

food fed to each of them, and a description of all food

purchased. The maximum daily ration of oats was as follows:

| |

|

|

|

Class of horse |

Hard Working |

Light work or

Non-working |

|

Heavy dray, cart horses, and trotting vanners |

16 lbs. |

12 lbs |

|

Light draught horses and light trotting vanners |

14 lbs. |

10 lbs. |

|

Other light horses and cobs |

11 lbs. |

8 lbs. |

|

Ponies of 14 hands and under |

7 lbs. |

5 lbs. |

Because industry concentrated on war work, there were

many shortages of all kinds of items in the shops, so 'make

do and mend' was the order of the day. |

|

|

In 1918 six battle-scarred tanks were

brought over from France to spend a week in many towns or

cities to raise money for the war effort. In Wolverhampton,

Tank number 119 "Old Bill" paraded through the town to the

Town Hall on 4th to 9th February. £1,425,578 of War Savings

was raised. From 28th October to 2nd November in Gun Week,

six howitzers were put on display, and £920,000 was raised

towards the war effort.

In 1918 after a German offensive along

the western front, the Allies and the American forces

successfully drove them back, leading to the armistice on

11th November, 1918, and victory for the Allies. Church

bells rang, factory hooters sounded, flags were flown

everywhere, and large crowds gathered in the streets. The

end of hostilities was celebrated by a thanksgiving service

held in the market patch, and on the steps of St. Peter’s

Church. The peace agreement was formally signed on 28th

June, 1919.

The aftermath

In November, after the war, the Prime

Minister, David Lloyd George, who stayed at the Mount as a

guest of the Mander family, received the Freedom of the

Borough. He gave a speech from the Town Hall balcony and

urged Wulfrunians to 'light the road along which England

shall march to a nobler future'. Whilst in Wolverhampton he

started his election campaign at the Grand Theatre.

Over 1,700 Wolverhampton men did not

return from the war. Their details are recorded in the

town’s roll of honour. Plans were made for the building of a

suitable war memorial to commemorate those who had fallen. A

War Memorial Committee was established in 1919, and after

much deliberation, a contract for the building of the

memorial was given to William Sapcote and Sons Limited, of

Birmingham, in June 1922.

|

|

The war memorial. |

The memorial, built at a cost of

£1,888, was sculpted by Mr. W. C. H. King of Hampstead,

London. Red sandstone was used, to match the stone of St.

Peter’s Church. The simple column is decorated with four

statues at the top, one for each of the armed forces, and a

fourth representing St. George, the patron saint of England.

It had been decided that the memorial

would carry no names, just the following simple inscription:

‘In Grateful Memory of Wolverhampton Men Who Served in the

Great War 1914 -1919’.

The memorial was unveiled on Thursday

2nd of November, 1922 by Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton

Sturdee. Also present were members of the council,

representatives of the police, firemen, postmen, and members

of the boys' brigade, scouts, and guides.

|

|

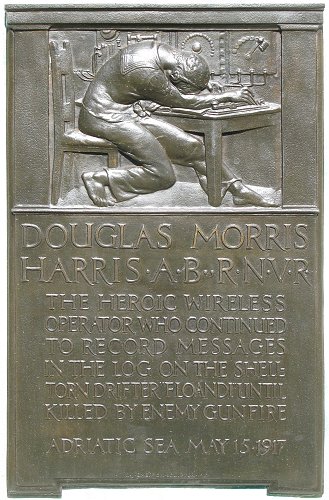

Several other war

memorials were erected around the Borough, including one

built in 1919 in St. Peter’s Gardens to commemorate Douglas

Morris Harris. It features a bust by Robert Jackson Emerson.

The Harris Memorial is dedicated to

Able Seaman Douglas Morris Harris who was born in 1898 at 49

Penn Road. By 1911 the Harris family had moved to 42 Lea

Road.

He initially worked in a bakery before joining the

navy, and being posted to HMS Admirable. He was later on

loan to the Italian navy, and joined the crew of an armed

Italian drifter called ‘Floandi’. The drifters were used to

blockade the port of Cattaro to prevent the Austrian Navy

from using the Adriatic.

|

|

The Harris memorial. |

|

The front plaque. |

|

|

The Emerson bust on the Harris

Memorial. |

|

On the night of 14th to 15th May, 1917,

the drifters came under attack from three Novara Class

Austrian cruisers, SMS Helgsland, SMS Novara, and SMS Saida.

On that fateful night, Douglas Harris, who was the wireless

operator on the ‘Floandi’, remained at his post while his

ship came under heavy fire.

He continued to send messages,

and make entries in his log until he was killed by a piece

of shrapnel. He died on 15th May, 1917 at the age of 19.

Although he was not awarded for his bravery in this country,

he was awarded one of Italy's highest honours. |

The plaque on the rear of the

memorial. |

|

One of the town’s servicemen, Corporal

Roland Elcock received a Victoria Cross for his

single-handed attack on a German gun position on 13th

October, 1918. Later that day he attacked another enemy

machine-gun and captured the crew. He was 19 at the time. A

civic reception was held in his honour in February 1919, and

he joined other medal winners at the Hippodrome to be

presented with a gold watch.

On the evenings of Tuesday 18th March, 1919

and Wednesday 19th March, 1919 a

dinner followed by entertainment was held by the proprietors of the Express and Star,

N. B. Graham, and J. D. Graham, at the Baths Assembly Rooms,

for the 913 ex-prisoners of war from Wolverhampton and the

Black Country, on their return home. Peace celebrations were

held in Wolverhampton on Peace Day, 19th July, 1919. On 16th

October, Field Marshal Earl Haig visited Wolverhampton to

receive the Freedom of the Borough.

Anti-German feelings were so high that

suggestions were made by the council, to remove the Prince

Consort's statue from Queen Square, to show public

disapproval of his German connections.

The war greatly helped the cause of

women’s emancipation and gave them a greater degree of

independence than before. Although many women lost their

jobs when the hostilities ended, and the men returned, they

now had a more prominent role in society and increased

expectations for the future. The Representation of the

People Act 1918 gave women over 30 years old the right to

vote, but they had to be a member, or married to a member of

the Local Government Register, or a graduate, voting in a

University constituency. They had to wait another ten years

until the passing of the Representation of the People (Equal

Franchise) Act 1928 to gain the same voting rights as men.

The Economy

Immediately after the end of the First

World War, there was a short-lived boom in the economy,

which lasted until late in 1919, but things rapidly went

downhill.

The early 1920s were a time of recession, a time of hardship

for many people. The First World War greatly stretched the

nation’s finances. It disrupted our trade, and led to the

rise of foreign competition, and the loss of many of our

traditional exports, including steel, coal, and textiles.

The country had previously grown wealthy because of its

pre-eminent trading position in the world, the loss of

which, led to the decline of many of our once great

industries, and substantial job losses.

The war had been funded by selling foreign assets, and

borrowing large sums of money, which led to a large national

debt. Britain’s interest payments amounted to around forty

percent of the national budget. In 1920 the rate of

inflation was twice as high as in 1914, and the value of the

pound fell. It would take many years, and the threat of

another world war for the situation to improve.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|