|

Chapter 4.

The English Cup Final of 1908. “Ravenous Wolves”

Hunt's reputation and record

as half-back for the Corinthians and Oxford City Reserves

were good enough for him to be selected for the England team

against Wales in the April of 1908. However, he was to

forsake this honour in order to turn out for Wolverhampton

Wanderers in the Cup Final of that year.

Kenneth Hunt had started

playing for the Wolves on a part-time basis at the start of

the 1907-8 season. Not for the last time in their history

were the Molineux Club suffering a financial crisis, and so

were undoubtedly very glad to be able to avail themselves of

the services of the very fit and keen undergraduate, who

would only accept travelling expenses, rather than

jeopardise his amateur status. Only two years before Hunt

had agreed to play, Wolves declared a mere profit of

£119.6s.8d, compared with nearly £950 made by local rivals

Smallheath, (now Burmingham City), and £2,000 by Aston

Villa.

|

|

The English F.A. Cup of 1895.

|

Things did not improve over the ensuing two

years and by Christmas 1907 the town's evening paper, the

Express & Star were so concerned about the club's plight that

they offered financial assistance for the purchase of players.

Thus, the availability of someone of Hunt's experience must have

seemed like a godsend to the Wolves' Board. Hunt would finish

his studies on a Friday afternoon and make his way by train to

Wolverhampton. After spending the night at his parents' home in

Chapel Ash he would be available for team selection on the

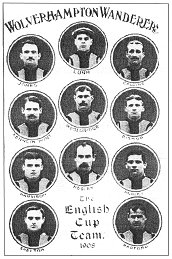

afternoon of the following day. The Wolves team that Kenneth

Hunt joined presents a rather strange picture compared with its

modem counterpart, and if the conventions of those days were

employed by a team now the F.A. will not permit them to play in

competitive games. |

All of the Wolves players wore identical old

gold and black striped shirts, including Lunn, the goalkeeper.

It seems odd that he was the smallest man in the team. Although

he was prone to being shoulder-charged over the goal-line by

opposing forwards caught in possession of the ball, he had more

freedom of action than his modern counterpart in as much as he

could handle the ball outside his penalty area. |

An advert for football equipment from

the early 1900s. |

| Another advert

from the early 1900s. |

|

None of the players wore numbers. (This

practice only came about in 1933 when identification numbers

were needed by radio broadcasters commentating on a match.)

Training for the 'big one' seems to have been a rather

leisurely affair for the Wanderers' players compared with

the rigours a present-day team would endure. They did some

work to develop their ball skills, but Albert Fletcher, the

trainer, also organised long healthy walks in the

countryside around Matlock, (where the team were staying for

a week prior to the Final), which the players undertook

whilst dressed in three piece suits and flat caps! |

|

Considering the state of the Club's

finances, and the inability to buy 'crack players', it is

not to be wondered at that the Wolves team of 1908 were a

mediocre outfit which held a mid-way position in the second

of the two divisions that constituted the English Football

League at that time. In the previous year they had managed

to gain sixth place in the lower division, although they had

been knocked out of the Cup in an early round by Sheffield

Wednesday who were the eventual winners.

Wolves had not got a good record in the

Cup competition up to that time, having only won it once in

their history, (in 1893). Indeed, a Cup-tie against the

Wolves would have been considered a lucky omen by many

teams, as by 1908 they had been dumped out of the

competition by the eventual winners on no fewer than eight

occasions.

|

|

| This, together with the fact that the

competition had only once before been won by a Second Division

Club, makes Wolves ultimate achievement in 1908 even more

remarkable. |

| A cigarette card

of Kenneth Hunt from c.1909. |

|

Against all odds Wolves reached the Final in

1908, fortunately winning all their matches in the previous

rounds by narrow margins. In a tie against Swindon earlier in

the year, Kenneth Hunt had come on for Wooldridge, the Wolves

skipper, who had been injured. In true heroic style he changed

the run of play, and helped Wolves snatch a victory, even though

he was knocked unconscious twice in the course of the match. The

three Cup games prior to the Final were not so dramatic for

Wolves, but they were very close run things. The team scored

only seven goals, whereas their opponents in the Final,

Newcastle, had hit the net no fewer than eighteen times in the

corresponding ties. In sharp contrast to Wolves, Newcastle at

the time were 'riding on the crest of a wave'. They were one of

the most successful clubs in the history of the game before the

First World War. They were the previous season's Champions and

had reached the Cup Final no less than four times in the seven

seasons between 1904 and 1911. |

| As might be expected, the Geordies' confidence

was sky-high prior to the Final, and the club requested

permission to have the team photographed with the cup before the

Final had even taken place. In the light of subsequent events,

there must have been many Magpie supporters who were eternally

grateful that the request was refused. This confidence in a

predicted Newcastle victory was not felt on Tyneside alone. |

|

Despite parochial and partisan emotions

felt by people in Wolverhampton, neutral pundits had little

doubt as to the outcome of the thirty-fifth annual Cup

competition. Wolves were described in the London press as a

"rough and tumble team", and sharp contrasts were made with

the smooth and silky skills of the Newcastle side they would

meet at the Crystal Palace; (the ground which had been used

to stage the Final of the competition since 1895). On the

morning of the game the "Sporting Life" declared "there is

no comparison on paper. Newcastle should win in handsome

style."

Not surprisingly 'Cup Fever' had

gradually built up in Wolverhampton as the Wanderers had

progressed through the various stages of the competition.

One local newspaper planned to utilise the technological

advances of the day to bring details of the Final to

Wulfrunians as quickly as possible.

|

Kenneth Hunt in 1908. |

|

The Directors of the Express and Star

stated that they were willing to personally bear the expense

of having a 'new fangled' telephone line installed between a

small wooden hut in the Crystal Palace ground and their

Queen Street offices. Costing 45/- per hour the telephone

would be used by a correspondent at the match to transmit

the score at regular intervals to the newspaper office in

Wolverhampton. This would be conveyed to the crowd assembled

in Queen St. by it being chalked up on a large blackboard,

which was to be suspended out of an upper-floor window for

all to see. Other commercial interests also used the

occasion for topical publicity, and readers of local papers

were assured by advertisers that the winners would be the

one whose players invested a 'lucky sixpence' to purchase

their cocoa! The 'Oxo' company also exploited the interest

in the Cup by putting on a competition in the local papers.

The prize for the several lucky winners was to be "a free

trip to London and back, with reserved and numbered 5/-

seats at the Palace".

|

Crowds outside the Express & Star

offices following the progress of the Cup Final. |

The Wolves Trainer, Albert Fletcher, had

endorsed this product by stating "Our players speak highly

of Oxo, and consider there is nothing like it for giving

energy and staying power".

Considering the poor understanding of

food values at that time, there is no reason to think that

beef extract drink did not indeed form an important part of

the team's diet in the build up to the Final.

|

|

With all preparations completed, the

legions of Wolves supporters made their way towards the

metropolis on the many 'special' trains which had been laid

on for that purpose. With the exception of the fortunate

winners of the Oxo competition, the total cost of the day's

outing, including transport and admission price would have

been very nearly the equivalent of an industrial worker's

weekly wage at the time. However, few true supporters would

have let that stop them going to the game.

The team had set off on the morning of

April 25th in a specially commissioned London & North

Western Railway Company train. The engine (named

"Messenger") had been decorated with flags and bunting, and

a sign declaring "Here come the Wolves!".

After many supporters from both sides had

attended a service at St. Paul's Cathedral, undoubtedly all

praying for ''the right result", the crowds made their way

to the Crystal Palace. The weather had been very poor and

totally out of keeping for the time of year. Snow had caused

the cancellation of games at Southampton and Reading and

conditions at the Crystal palace ground were described as

"Rain in torrents and pitilessly driven sleet, alternated

with heavy snow showers"

However just prior to the game the stormy

skies were replaced by bright sunshine. It was surely an

omen that black skies and white snow gave way to golden

'Sunshine on that day, in a way that the black and white

colours of the Northerners would succumb to the 'old gold'

of the Wolves. Watched by less than 75,000, (the smallest

crowd for several years), the game kicked off at the

appointed time under the control of Referee Mr.

T.P.Campbell. The heavy weather had made the embankments

slippery for spectators, but this did not stop one Wolves

fan from appearing in a home made fur Wolf suit. Despite the

effect being somewhat spoilt by the lack of a wolf mask and

the wearer insisting on retaining his flat cap, many must

have envied his outfit on such a cold day! Others at the

game included both the Mayors of Wolverhampton and

Newcastle; Sir Alfred Hickman (the Wanderers President), and

the famous politician A.J. Balfour, (leader of the

Conservative Party and one time Prime Minister of Great

Britain). The initial play heralded dire warnings for the

Midlanders. Skill and training gave way to nervousness and

uncertainty. Newcastle, by far the more composed side,

mounted several early attacks. As if overawed by the big

occasion, Wolves allowed gaps to develop between the

forwards and the half-backs, and these were duly exploited

by the Tynesiders. At the other end of the park Wolves

attackers, Pedley and Radford, had their efforts thwarted by

the Newcastle international defender, Gardner, on several

occasions. The other Wolves' forward, Hedley either slipped

or failed to put in a proper shot when in front of goal,

even though he had already completed a lot of hard work in

receiving long passes and getting the ball under control.

There was a tendency for the Wolves attackers to try and

'walk' the ball into the net, but considering the Newcastle

team's skill and experience this type of play would always

be fruitless. Something dramatic was needed to break the

deadlock and lift the Wolves.

|

| "Cometh the hour, cometh the man" is an old

adage, but never more true when recalling Hunt's actions on that

day so long ago.

After nearly forty minutes, a feeble and messy scramble in

the Newcastle goalmouth saw the ball cleared by a defender's

long kick. It was intercepted by the Oxford graduate who was

standing some forty yards upfield. Hunt's next action

brought him some brief national fame, but more lastingly,

ensured his elevation to the ranks of the all-time heroes of

Wolverhampton Wanderers. |

|

| Calmly and thoughtfully Hunt struck the ball

back towards the opposition's goal with such ferocity that the

Magpie's goalkeeper could do nothing but embarrassingly palm the

ball into his own net. Hunt's goal has been described as

'speculative' and even 'lucky' by analysts who reason that he

was not a proven or regular goal-scorer and was not in the habit

of trying long range shots. There may be some truth in

long-range shots. There may be some truth in this as it was the

only goal he scored for Wolves that season, but what a time to

score it! His reason for trying a shot will never be known, but

more important was the effect that it had on the rest of the

Wolves' players. The team suddenly believed in itself and the

vague possibility of a win became an almost certainty as the

Wolves piled on the pressure. Whereas before Hunt's goal almost

nothing had gone right, now the Midlanders could hardly put a

foot wrong. The Wanderers hustled, bustled, jockeyed their foes

and fought for every ball, grasping at half chances at every

opportunity. The Newcastle team were taken aback at this newly

found dynamism from the team that they had so recently dismissed

as 'no hopers', and were at a loss in knowing how to handle the

Wolves determination and aggression. Hunt himself led the way in

maintaining the pressure. His speed and power were phenomenal,

and Wilson, one of the Geordies who was detailed to mark him

ended up 'doing the splits' whilst attempting to catch Hunt who

was running with the ball.

The Molineux men went further ahead in the 'second half

through Hedley and Harrison, before exertion and strain

started to take its toll. Newcastle managed to score in the

dying minutes of the game through Howie, but by then it was

far too late for the Magpies to salvage anything more than a

little pride from a game that they expected to win so

easily. (Apart from scoring for Wolves, Billy Harrison would

have greater reason to remember that day, for whilst he was

playing at Crystal Palace in the Final, his wife was back in

Wolverhampton giving birth to triplets! Strangely Howie's

goal for Newcastle meant that all the players on the park

that day whose surnames began with the letter 'H' managed to

score).

The final whistle was greeted by scenes of wild excitement

on the Crystal Palace terraces. Wolves fans cheered

themselves hoarse as the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Henry

Bell, handed the trophy to Wooldridge, the Wolves skipper,

who boastfully declared to loud applause that it would not

be the last time that he would have the honour of receiving

it. (Sadly it was!) Newcastle took their surprising defeat

in good part as W. Hudson, M.P. for Central Newcastle, gave

an impromptu speech in which he congratulated the Wanderers.

Although unexpected, Wolves victory was very popular in

various parts of the country. |

Wolves victory is hailed in the Daily

Mirror. |

At a match on Merseyside between Everton

and Sheffield Wednesday, (the Finalists from the previous

year), the underdogs' victory was greeted with great cheers.

The news of Wolves success was greeted in

Wolverhampton by scenes of great excitement, especially

outside the Express & Star offices in Queen Street, where

crowds had been arriving by tram all afternoon to hear

reports on their team's progress. Spotted amongst the crowd

was the Reverend Robert Hunt, Kenneth's father, who was as

keen as anyone was to hear the news from London. In what was

considered an outlandish display of fanaticism for the

victorious team, a resident of Park Village devised a flag

in Wolves colours and hoisted it up outside his house.

|

|

At Dudley and West Bromwich the news

caused crowds to congregate on the streets to excitedly

discuss the victory.

In true sporting spirit the Wolves Board

received a congratulatory telegraph from West Bromwich

Albion, and this was duly published in the

local press. Other local reactions to the victory were

somewhat strange. In a letter to the editor of the Express &

Star one correspondent advocated a change in Wolves colours

away from the "dowdy and dull gold and black" to a more

cheerful red, which would be more fitting for a winning

side. (perish the thought!)

There has been much debate about the

reasons Wolves won this famous Cup Final. There was no doubt

why the local newspapers thought that Wolves had been

victorious. Quite simply they stated "Wolves won because

they were superior!... The Wolves were the keener team, they

had more of the game and were deadlier at goal they won the

last yard every time."

This may be true of the latter part of

the game, but it could not be said of their performance

throughout the ninety minutes. A great deal was made of the

fact that the Wolves team was made up of not only 'local'

men, (which it wasn't! e.g. Hedley had been born in Durham),

but more to the point of 'Englishmen'. Rather pompously,

local sources felt it fitting that the 'English Cup' should

be won by an 'English team'.

This was a rather churlish swipe at

Newcastle who had fielded several Scottish signings amongst

their Final line-up. The national press was not so

jingoistic or partisan in their appraisal of the game, and

singled out Kenneth Hunt for particular praise. Papers like

the Daily Mail described his play as 'classy' and 'stoic',

and others identified his enthusiasm, tenacity and example

as being the key to the ‘Wanderers’ success. When

interviewed later, Hunt himself modestly stated that Hedley

was the shining example of the Wolves team, and further

played down his own part in events by stating that Newcastle

had the "cleverest half-backs" in the game. In his opinion

Wolves had won because their game plan was simple. “We

hustled” he said, “We only ever intended to hustle". He also

later summed the game up mathematically. "Newcastle played

75% of the football - we scored 75% of the goals!"

Hunt's popularity as a local hero to the

people of Wolverhampton now knew no boundaries. He and the

rest of the team were mobbed when they rather unwisely tried

to stop at St.Mark's Vicarage for "light refreshments".

Whilst parading the trophy through Wolverhampton two days

after the game Kenneth Hunt was then carried on the

shoulders by jubilant fans up to the Molineux Hotel whilst

the crowd sang a popular song of the time "The Boys of the

Old Brigade".

Hunt was always a very competitive

player, and has been described "as hard as teak", but his

reputation for fairness with the Wolverhampton public had

been high since the Swindon match. A collision between Hunt

and an opponent called Chambers had resulted in the latter

being taken into hospital. In true sporting spirit Kenneth

Hunt had taken a considerable detour on his journey from

Wolverhampton to Oxford to twice visit the man and enquire

as to the progress of his recovery.

There was a strong local pride in Hunt's

triumph and people wanted to show how living in

Wolverhampton had helped him. This feeling was articulated

in the month following the Final, at the annual Dinner of

the Grammar School Old Boys' Association, (the 'Old

Wulfrunians'). G. Bancroft, who had been a contemporary of

Hunt at the school six years earlier, stated unequivocally,

(but rather too simplistically,) that the Wolves' hero had

"learnt his craft as a footballer at the Grammar School, and

not at Trent College".

So, what is the true significance of the

1908 Cup victory and Kenneth Hunt's part in it. The game

itself certainly brought fame to the Club. The Wolves of

1908 were to have the distinction of becoming one of the

last winners of the F.A. Cup of that time, which itself was

a replacement for the original trophy, which had been stolen

in 1895.

The 1908 Cup, which had cost £20 and was

rightly entitled the 'English Cup' was replaced in 1911 by

the present trophy because the design had been pirated. The

old trophy was presented to Lord Kinnaird, the President of

the F.A. who had witnessed the Cup Final of 1908 and was a

man whose record number of Cup Winners medals has never been

surpassed. The Express and Star saw the success in terms of

potential publicity for the town and noted that it was

important that the game had showed the London public what

the Wolves could do.

Probably the most significant fact was

that Wolves benefited financially to the tune of £3,000,

which went along way to easing their financial worries, and

probably saved them from subsequent bankruptcy in the period

before the Great War.

In personal terms the game indicated

Kenneth Hunt's love of the Wolves. He had been selected to

represent England against Wales at that time, but had

declined the offer, preferring to turn out for Wolves in the

Final. For Kenneth Hunt the victory brought him immediate

opportunity and lasting respect and fame. Within six months

he had been selected to play for the victorious Great

Britain side in the London Olympic Games Football

Competition. By being a member of the side that

defeated-Denmark 2-0

in the Final, (in what was described as a "poor game"),

Hunt had achieved the unique and honourable distinction of

winning an Oxford 'Blue', F.A. Cup Winner's Medal and

Olympic Gold Medal all in a twelve month period.

Although he later achieved other

successes, such as England Caps and a Runners-Up Medal in

the Amateur F.C. Cup with Oxford City four years later, his

career as a footballer could never again reach such dizzy

heights.

Hunt played for the Wolves for one more

full season before moving on to Leyton Orient and Oxford

City, although he returned to Molineux on occasion. He

planned to return to the Molineux to play a final couple of

full games in Wolves' colours in the Spring of 1920, almost

twelve years to the day that the Club had won the Cup, but

due to his uncle Joseph's sudden death, his appearance was

limited to a single game. Wolves were again going through a

very severe financial crisis, and there were public meetings

held in which the resignation of the Board was called for.

Despite this, over 15,000 people turned

up to see the thirty six year old Clergyman lead Wolves to a

fine 4-0 victory over County neighbours, Stoke City. In all

Kenneth Hunt played 61 times for the Wolves, including a

Charity Match in 1916. He often turned out for Wolves during

vacations from his teaching post at Highgate School. His

final appearance at Molineux was during the Second World War

when he played in a practice match, even though he was well

into his fifties!

For a time Hunt had become the archetypal

Edwardian hero. His display of grit and determination

against great odds endeared him to the English people before

the holocaust of the Great War caused them to them to become

more uncertain about the World and their place in it. Apart

from his awards and medals, Hunt still holds the distinction

of being the last of only three amateur players to win an

F.A. Cup Winners Medal once professionalism had been

legalised. He also has the distinction of still being the

oldest man to represent England at International level,

whilst remaining totally amateur. (This was in the Antwerp

Olympics of 1920 when at the age of 34 he played against

Italy and France). Perhaps the most enduring reminder of

Kenneth Hunt is in the hearts of all true football fans when

they read about the past glories of the game. In this way,

even though he was not a priest at the time, the 'Reverend'

Kenneth Hunt's name, fame and reputation will live on

forever.

|

|

|

|

Return

to

Chapter 3 |

Return

to

the contents |

Proceed

to

Chapter 5 |

|