|

|

Cyril Kieft

by Jim Evans |

|

| The Early Years Cyril Kieft was born in Swansea and followed his father into the

steel industry. By the time war broke out he was managing the giant

steel-works at Scunthorpe and was a regular visitor to Donington Park

where he saw the legendary pre-war grand prix. His appetite for cars and

for motor sport had been whetted and the memory of those races led him

to buy a Marwyn 500cc car after the war - but his competition career was

brief. He entered a hill climb at Lydstep in Wales and recalled: "I was

on the starting line when one of my two daughters ran up and said:

‘Mummy says: be careful.’" I did one run and retired. I realized it was

madness for me to be doing it and, afterwards, I never employed a driver

who had children." |

|

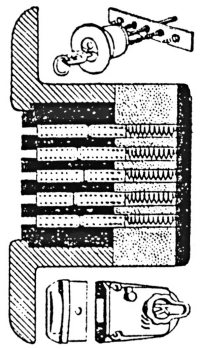

Kieft's 'K' type lock. |

In 1947 Cyril left the steel industry when it was

nationalised, fearing he would become no more than a civil

servant. He set up Cyril Kieft and Co Ltd., forging and pressing

companies of his own, based at Bridgend South Wales. Rolls-Royce

was a customer. He also started to manufacture a cylinder pin

tumbler lock known as the ‘K’ type, which differed from the

normal design in that the pins were in an almost straight line,

end on to the face of the cylinder.

Another feature of the lock

was that the plug could be locked in two positions, which was

used to deadlock the latch. It was manufactured in the early

1950s. Initially it sold well but some problems were experienced

and the troublesome lock disappeared from the market.

Motor racing offered Cyril a new challenge. When Marwyn

folded, Cyril acquired the remnants of the company and then

designed his own car. The chassis of the first Kieft 500cc car

was similar to the Marwyn but the suspension, by Metalastic

bushes in tension, was completely different. |

| The early Kieft's enjoyed some success but were heavy compared to the

rival Coopers. Michael Christie, however, fitted one with an 1100cc

V-twin JAP engine and ran it in hill climbs. Michael, who was five times

runner-up in the RAC Hill Climb Championship, says: "It was a brute

force and ignorance car, but it gave me some wins." In the early days of 500cc racing everyone was on a learning curve

and Kieft did better than most. For one thing, Cyril sold several cars -

eight of the original design -and was a professional in an amateur age.

He understood presentation and the press: his transporter was always

smartly turned out and he was the most quoted manufacturer of his time.

The first Kieft Sports car was essentially a wider Formula 3 car with

cycle mudguards, headlights and a 650cc BSA engine. It would do 75mph

and return 40mpg, respectable figures for the day. Cyril made it known

that he would take orders for others, but nobody took him up. In late

1950, Kieft tackled 350cc and 500cc international records at Montlhery.

The driving team consisted of Stirling Moss, Ken Gregory (Moss’ manager)

and a Kieft owner called John Neill. They came away with 14 records.

Cyril asked Moss to drive for him, but Stirling did not rate the cars.

Instead, Kieft Cars took over a 500cc design conceived by Dean Delamont,

John A Cooper (technical editor of The Autocar) and Ray Martin, to

Stirling’s specifications. It was an advanced design with

all-independent suspension by rubber bands. As part of the deal, Moss

became a director of Kieft Cars Ltd and they moved to Reliance Works

Derry Street Wolverhampton.

The Wolverhampton

Era

While the new car was being made, Stirling drove one of the older

models in the Luxembourg Grand Prix. In the back of the car was a

double-knocker Norton engine, up-rated by Steve Lancefleld, the best

motorcycle tuner of his day. Norton wanted nothing to do with the car

brigade so people had gone to the trouble of buying motorcycles just to

get their hands on the engine. Cyril, however, sponsored Eric Harding,

one of the works Norton riders, so he enjoyed unusual influence.

Stirling retired at Luxembourg but it was there that the designer of the

Mackson 500cc car, Gordon Bedson, made an approach to Cyril. He was

working with Vickers Aircraft and wanted to move over to cars. Towards

the end of 1951 Cyril gave him the job and, with typical generosity,

fixed him up with a house. Moss received the new 500cc car in time for

Whit Monday at Goodwood, where he duly won the final, setting the

fastest lap and a new lap record. For 12 months Moss and the prototype

Kieft were the headline news in Formula 3. Then the prototype was

written off in a multiple shunt in Belgium and Stirling was less happy

with production versions. At Boreham, on the 21st June 1952,

Stirling had entered his usual Kieft but arranged to borrow a works

Cooper for the event, the Kieft in his words "finally having run out of

steam". As the Motor

wryly observed "a director of Kieft Cars was thus competing against

Kieft in his rival’s product!" During the year Moss drifted back to

Cooper.

|

| Kieft remained Moss’ biggest rival in the form of

the works driver Don Parker, who was taken on for 1952. Don was

over 40 before he even saw a racing car and was 44 when he

became Kieft’s works driver. He was built like a jockey; he had

a lot of aggression and was a fine engineer who honed his cars

to the limit; he even raced without underwear or socks to save

weight.

Don won most of his 126 Formula 3 victories in Kieft’s,

and was the only driver to beat Moss on a regular basis. He was

British Champion in 1952 and 1953 and thought he had won in 1954

as well. He was hailed as the champion in October but then the

BRSCC organized the first Boxing Day Brands Hatch meeting and an

extra round was added. Les Leston finished above Parker and took

the title by half a point.

Parker, who died in 1997, had a

volunteer mechanic, a young chap who hitchhiked to meetings to

lend a hand and who remembered: "He picked me because he thought

I could persuade Cyril to give him a drive." His name was Graham

Hill. |

|

| There are no precise records as to the number of F3 cars built but it

seems to be a total of around 15 during 1952-53. The 1954 version

featured tubular wishbone and coil spring front suspension, but probably

only a couple of these cars were built. Bedson's brief was to design a Bristol-powered Formula 2 car, but

this was never completed and instead the same basic design was adapted

as a sports/racing car in 1953. The basis of the sports Kieft was a

multi-tubular chassis with the then unconventional feature that the

central seat of the proposed Formula 2 car was retained. Cyril had been

impressed by the center-seat Veritas Meteors at the Nurburgring. The

idea was that sitting in the center seat would give optimum weight

distribution. But the driver sat high over the prop shaft with the gear

lever between the legs, the intention being that there should be small

seats on either side of the driver outside the main chassis frame. Thus

it was, strictly speaking, a 3-seater and complied with international

regulations, although in practice the seat to the right of the driver

was usually removed. There were unequal-length tubular wishbones front

and rear with coil spring/damper units at the front and a transverse

leaf spring at the rear, mounted on top of the Elektron housing for the

final drive. Kieft used a form of wheel and brake inspired by Cooper

practice, so that the ribbed Elektron drums for the Lockheed brakes also

formed the wheel centers and were bolted to detachable steel 15 in.

rims. There was full width ‘aerodynamic’ bodywork constructed in

aluminium, with front and rear body sections hinged to give excellent

accessibility, a passenger door on the left (getting into the driver’s

seat was a bit of a scramble!) and a metal tonneau over the right-hand

side of the cockpit. Prices quoted were £750 (less engine and gearbox),

£1125 (MG engine and gearbox) and £1365 (Bristol engine and gearbox).

According to Kieft, eight cars were built in 1953 and early 1954 and

were registered consecutively LDA1 to LDA8. If an attempt is made to

trace these numbers through illustrations in magazines and photographs

of the period, it is not possible to trace them all. However, early in

the year arrangements were made for three cars to be raced by "The

Monkey Stable" and these were registered LDA1 to LDA3. Originally The

Monkey Stable was to have four cars but it seems that only three were

delivered. According to Cyril Kieft the cars were leased but, on the

face of things, this was not correct. Peter Avern, The Monkey Stable

racing manager, advertised two cars for sale in October 1953, whereas if

they were leased they would presumably have been returned to Kieft. It

may be - and this is speculation - that the cars were originally sold

but a replacement supplied later in the year was on lease. The Monkey

Stable cars used MG 1467 cc engines and MG TC gearboxes and the engines

were tuned by team drivers Jim Mayers and Ian Wilson. Of the remaining

cars built it appears that one (supplied to a private owner for road

use) was MG-powered and the remaining four were all fitted with Bristol

2-litre engines and gearboxes.

In 1953 The Monkey Stable was very professionally organised and

tackled a full season of International races with some success. The full

team of three cars was entered in the Production Sports Car race at

Silverstone and, although they were beaten in the 1500 cc class by Cliff

Davis’s Cooper-MG, they finished second and third in the class, in the

order Mayers, Griffith; but Keen was right at the tail of the field

after mechanical problems. In this race Michael Christie drove the first

of the Bristol-powered cars entered by ‘Kieft Cars’ but he was never in

serious contention in his class. The Kieft’s were again beaten by

Davis's Cooper in the 1100 cc heat of the British Empire Trophy on the

Douglas circuit but, in the handicap final, although Meyers non-started

because of clutch trouble, Griffith came through to win the class at

63.80 mph after the Cooper broke a half-shaft. On 26 July The Monkey

Stable competed in the Lisbon Jubilee Sports Car Grand Prix. The race

was won by Bonetto’s Lancia, with Moss (works Jaguar) second, and the

Kieft-MGs won the 2000 cc class in the order Mayers, Line.

More Racing

The Monkey Stable's transporter, with two Kieft-MGs, was driven

direct to Nurburgring so that the team could compete in the 7-lap Sports

Car race prior to the German Grand Prix. The third car for Mike Keen

came direct from England. On the way the transporter was wrecked and the

cars badly damaged. Gordon Bedson organized a replacement which was

driven to Germany and that was wrecked on the way too! David Blakely was

to have driven one of the cars but was now a non-starter, and Alan Brown

took over a car that Kieft was about to sell to a private customer. In

the race Brown was right out of the picture because of engine trouble

but Keen finished fifth in the face of strong local opposition from

Porsche, Borgward and EMW.

Because of the problems encountered abroad, The Monkey Stable missed

the Goodwood Nine Hours race, although Hazleton/Thompson drove a 2 litre

Bristol-powered car. It was plagued by an engine misfire and retired

because of a blown gasket. A week later The Monkey Stable ran their trio

of cars in the Nurburgring 1000 km race but the sole finisher was the

car of Mayers/Griffith, fifth and last in its class. Line over-revved

his engine on the first lap and Keen led his class but retired out on

the circuit because of a broken wheel rim. In the Tourist Trophy on the

Dundrod circuit a trio of Kieft-Bristol’s was entered under the name of

Kieft Cars but at least two of these belonged to private owners. None

finished and two of the three were eliminated by accidents. Mayers wound

up The Monkey Stable’s season by winning the 1500cc sports car race at

Castle Coombe in October and setting a new class lap record of 78.85

mph.

|

|

At the end of 1953 The Monkey Stable temporarily

pulled out of racing and most of the Kieft’s changed hands.

Horace Gould acquired one of the Bristol-powered cars to replace

his Cooper-MG but, even with his very press-on driving (not for

nothing was he known as ‘the Gonzalez of the West Country’), he

could not achieve success.

Probably his best performance was a

class second at the May Silverstone International meeting. In

British events the 1953 Kieft’s scored nothing apart from a

class win by Byrnes with a Bristol-powered car at Shelsley

Walsh. Much better luck was enjoyed by a Bristol-engined car

which went to America. Owned by Paul Ceresole and driven by

Carpenter/van Driel, it finished sixth and won its class in the

1954 Sebring 12 Hours race.

Three MG powered cars were entered,

Allen and Ehrmon finishing 11th

overall and 5th in its class; the other cars retired.

By the end of 1953 Cyril Kieft had his mind on a host of new

projects, despite the comparative failure of these early

projects. |

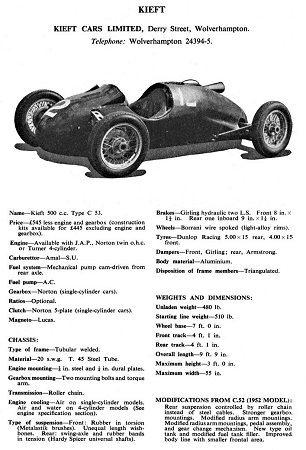

| A Formula 1 design was completed during 1954 with the intention of

using the Coventry Climax ‘Godiva’ V8 engine but, when Climax did not

release the unit, the project was stillborn. A car and a spare chassis

were made and Bill Morris, who has some Godiva engines, was still

completing the Fl Kieft in 1999, 44 years after it was intended to run.

However a Kieft did take part in a Formula 1 race. At Davidstow in

Cornwall, on the 7th June 1954, Horace Gould had entered his Cooper

Bristol for the Formula 1 race. The Cooper Bristol had retired from an

earlier race with engine problems but Horace was not going to miss the

Formula 1 race. So he came out in his Kieft Bristol Sports Car to do

battle. Rather strangely though, he was on the front row, while

technically he should have been at the back. The lighter single seaters

soon overtook him and, as the steering of the Kieft was causing handling

problems, Horace switched off the engine and retired. A little gem of

motor racing history that most people seem to have missed. This however was not the end of Horace’s eventful day, with both his

cars out of action he loaded them into his converted bus/transporter and

headed for home. On leaving the paddock he took a wrong turn and headed

down the main straight towards the footbridge. The bridge was low and

the bus was high. And the inevitable happened! The bridge collapsed and

the bus was almost cut in half. Fortunately no one was injured but the

remaining two races had to be cancelled. Horace was to live and fight

another day and entertain crowd through out England and Europe.

A one-off sports racer with a 5.5 litre V8 De Soto engine and a Moss

gearbox was built for an American amateur, Erwin Goldschmidt. It had an

aluminium body, which looked not unlike the Cunningham CR4. Goldschmidt

did quite well on the car’s debut in a hill climb; and then he pranged

it. Kieft sent out replacement parts and heard nothing for about 15

years, when someone discovered it on an airfield.

The real headline of 1954, however, was a new sports car with

conventional side-by-side seating. This was interesting because it was

the first car to have a one-piece glassfibre body. This was based on a

simple twin-tubular chassis with two main 3 in. steel members and the

familiar suspension arrangement of wishbones and coil spring/damper

units at the front and transverse leaf spring and wishbones at the rear.

It was the first car to use the new Coventry-Climax FWA single overhead

camshaft 1098 cc engine developing 72 bhp at 6300 rpm. Transmission was

by a Moss 4-speed gearbox. As Cyril explains: "Gordon Bedson sketched

out the body and I added my bit. We then had a one-fifth model made and,

because I was buying Bristol engines, we were able to put it in the

Bristol wind tunnel. The Climax FW was then a fire pump engine and that

is how I bought the first one. Then I had a crankshaft forged at my

works and machined at Laystall, and had new conrods made." As events

were to prove, its competition potential was limited, but it had good

prospects as a production sports car.

A four-cylinder water-cooled twin overhead cam 500cc unit, made by

Jack Turner of Turner Sports Cars, Merridale Street, Wolverhampton, had

intrigued Cyril. On paper the engine looked a winner and Cyril spoke of

building a batch of 25 sports car using it. The one engine which Turner

made was run in a Kieft in a couple of hill climbs and was found wanting

- it produced only 35bhp against the 50bhp of a decent Norton. Jack

Turner later adapted the dohc cylinder head to a BMC A-Series engine and

ran it in a Morris Minor.

Another unusual engine that Cyril took on board was the AJB

air-cooled flat four, designed by Archie Butterworth. He took delivery

of one of the early examples, which had Steyr cylinder barrels and

heads, and had these swapped for Norton equivalents. At the time, Cyril

spoke of mounting a challenge to Porsche, but the engine proved hard to

cool. The AJB-Norton-Kieft engine passed through various hands and, in

the 1970s, Ian Richardson used it in his successful sprint motorcycle,

Moonraker. Richardson used the engine for years with no problems and his

many wins make you wonder what might have been.

The main thrust of Kieft activities in 1954 was on production of the

new 1100 cc sports/racing car. Using the Coventry Climax FWA engine is

Cyril’s crowning achievement; Kieft Cars did not benefit, but the FWA

begat the 1100cc sports car class, which replaced Formula 3 as the class

for the aspiring driver.

A Kieft-Climax appeared at Le Mans in 1954, entered for Rippon/Black

and, although it was no match for the Duntov/Oliver 1100 cc Porsche 550,

it ran steadily until the back axle failed in the eleventh hour. Don

Parker drove one of these cars in the 1500cc sports car race at

Silverstone in July, finishing well down the field, but lasting the

distance to take third place in the 1100 cc class behind von Hanstein

(Porsche) and Reece (OSCA). At the Tourist Trophy on the Dundrod

circuit, two 1100 cc cars were entered by Kieft Cars Ltd. (in fact the

company was still known as Cyril Kieft & Co. Ltd.) for Ferguson/Rippon

and Parker/Boshier-Jones; and the private 1953 MG-powered car of

Westcott/ Bridget also ran as a member of the works team. Byrnes entered

his 2-litre car for himself and Adams. Ferguson/Rippon were the sole

finishers in the 1100 cc class, in twentieth place and second in class,

the first major success for Coventry Climax. Cooper and Lotus were both

soon on the case. Parker was at the wheel of the car he was sharing with

Boshier-Jones when the front suspension broke and poked through the

bodywork, while a broken gearbox eliminated the Westcott/ Bridget car

and the Byrnes/Adams entry was compulsorily retired because of body

damage after striking a bank.

In January 1955 John Bolster tested one of these cars for Autosport.

The performance figures encompassed a maximum speed of 104.5 mph, 0-60

mph in 12.6 sec (quite respectable in those days), a standing

quarter-mile in 18.2 sec and a fuel consumption of 30 mpg or

thereabouts. Bolster wrote:

"The 1100 cc Kieft is two cars in one. First of all, it is a

smooth, quiet and tractable sports model, with perfect road manners.

Fitted with the standard full-width screen, it would be quite

practical as an everyday conveyance, and the remarkable resistance

to impact possessed by fibreglass bodies might well prove valuable

on our grossly overcrowded roads.

"Secondly, it is a competition model, designed ab initio

for this work. Thus it already has brakes, road holding and steering

that are quite adequate for racing, and requires no extra equipment

for this purpose. The engine gave every sign that it will stand up

to the most grueling event, and this is the sort of car that may

well win victories by going on motoring when the rest have stopped."

In other words, a nice little club racer that could be used as an

everyday car as well.

By this time Cyril had his mind on other things, since the

Conservative government was in the process of privatising the steel

industry and he was preparing to return. He left motor racing before the

end of the year but was to leave it on a high note. Kieft’s achievement

in winning its class at Sebring and second place in its class in the

Tourist Trophy was the British motor racing highlight of the year. In

recognition of the feat, Kieft Cars was given a stand at the London

Motor Show at Earls Court. They exhibited two 1100s, one in racing trim,

the other offered as a road car. The asking price was £1569, £500 more

than an Austin-Healey 100; and its one-piece body meant that the doors,

boot and bonnet lid had to be cut with a jigsaw - OK on a racer, but not

for a production car. Nobody bought one for the road. But the clock was

winding down and Cyril Kieft had lost vast sums of money on various

projects that were not pursued. Before the end of 1954 Cyril sold Kieft

Cars to fellow Welshman Berwyn Baxter, an able club racer. The sale was

kept quiet because Cyril felt that the team would have a better chance

of gaining entries in major races if the organisers believed that it was

business as usual.

In May 1955, one of the sports cars was fitted with an aluminium body

made by Panelcraft and a 1500cc Turner unit. The engine was a stroked

alloy-block Lea-Francis unit with a twin-plug head. It ran in the Paris

24 Hour race at Montlhery, but retired. In the early part of 1955 Baxter

drove this car, registered LDA 3 (the number was probably switched from

one of those allotted to a 1953 car, but exported), in Club events and

then ran it at Le Mans. For this race the fuel injection was replaced by

special Solex carburettors, which necessitated an enormous air scoop on

the bonnet. Baxter co-drove with John Deeley (an AustinHealey racer),

but the Kieft retired because of overheating on the sixth lap. A

Climax-powered car driven by Rippon and Merrick was also slow and failed

to finish. The Kieft-Turner failed to finish in the Goodwood Nine Hour

race. Baxter was now thoroughly fed up with the unreliability of the

inadequately developed Turner and substituted an Austin A50 engine for

the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod, where Baxter’s co-driver was Max Trimble.

An 1100 cc car was also entered for Lord Louth/Rippon, and a Bristol

engined car for Fisher and Adams. This car retired due to an accident

but the other two finished, but right at the tail of the field, the

Bristol engined car in 25th and the Austin engined car one

place lower. Berwyn Baxter entered the Kieft-MG in selected races during

1956, but only in British races, and then he called it a day. A total of

six two-seat Kieft sports cars were made.

Kieft Cars Ltd ceased to make cars in Derry Street, Wolverhampton

during 1956 and Berwyn Baxter transferred the company to Nixon’s Garage,

Soho Road, Birmingham, and shortly afterwards transferred to new

premises in Bordesley Road Birmingham. The company undertook the

preparation of competition cars in addition to Baxter’s own Aston Martin

DB3S and Max Trimble’s Jaguars. There were ambitious plans for marketing

a production version of the Kieft 1100ccc sports car but they came to

nothing. The company quietly faded away until the spring of 1960 when

John Turvey and Lionel Mayman bought the company and called it Burmans,

which, in 1961, made a few Formula Junior cars under the Kieft name; but

they were not successful.

Cyril had more tricks up his sleeve and his name was the ‘K’ in the

DKR scooter introduced in 1957. The initials were those of the three

people behind the project: Barry Day, Managing director of Willenhall

Motor Radiator, Cyril Kieft and Noah Robinson, a director of Willenhall

Motor Radiator. Cyril designed the frame and it was highly praised by

the motorcycle press. Willenhall Motor Radiator supplied the ten main

pressings and assembly took place in premises at Pendeford Airport,

Wolverhampton, where the machines were taken for final checking. But

scooters had to be Italian for credibility. About 2000 were made and

production finished in 1966.

Cyril Kieft shot across motor racing like a star for only a few

seasons, but he left an indelible mark.

References

Article in Classic Car and Sports car.

Locks and Keys (A newsletter for lock & key collectors) edited by

Richard Phillips, Nov. 2000

Powered Vehicles of the Black Country, by Jim Boulton, pub. by the Black

Country Soc., 1990.

Sport Racing Cars of the Fifties and Sixties, by Anthony Pritchard,

published by Osprey, 1986.

Formula 3 Year Book 1953-54, published by Motor Racing

Boreham: the History of the Motor RacingCircuit, by B Jones and J

Frankland, 1999.

Davidstow: a History of Cornwall's Formula 1 Race Circuit by Peter

Tutthill, 1996.

|

|

Return to the

previous page |

|