John Mander, Chemist, 1773 John Mander (1754-1827) was the second (surviving) son of Thomas Mander. (There was a third son, Thomas [1757-1813], who married Elizabeth, daughter of Edward Urwick of Felhampton Court, Wistanstow, Craven Arms, Shropshire, and settled in Birmingham.) He was born in John’s Lane and almost certainly attended the Grammar School, with his brother Benjamin also, in the same street. John Mander, Benjamin’s younger and, it has to be said, more commercially successful brother, was from the first apt and resourceful as a pioneer industrialist. He was apprenticed to the chemicals’ trade. There is no record of the indenture (Barty-King suggests he may have served at the alkali works of William Small (1743-75), at Tipton). But he gained a sound knowledge of the new industrial chemistry of the post-Enlightenment, pioneered in the Midlands also by John Roebuck (1718-94), Joseph Priestley and James Keir. He learnt his chemistry on the fringes of this enlightened circle, influential also on his political thought and religion. They were members of the great Lunar Society of Birmingham (c. 1766-1809), an informal group of fourteen men who formed a brilliant microcosm of a scattered community–‘gigantic philosophers’, empirical scientists, provincial manufacturers and professional men–who like him were typically religious dissenters and political radicals. They met in Birmingham on the Monday night nearest the full moon, when it was easier to travel, in order to discuss natural sciences and philosophy, and forge practical and commercial applications in manufacturing and industrial technology for the burgeoning innovations and discoveries of experimental science. They found England a rural society with an agrarian economy, and left it urban and industrial. We know that by 1773 (his twentieth year) John had finished his apprenticeship and accumulated enough capital to set up in business on his own in King Street as a manufacturing chemist and druggist. The chemicals works he founded was the first of its kind in Wolverhampton–it is still the only one in the Directory of 1781–and was effectively to prove the germ of the later Manders’ company. According to family tradition, John, precocious in chemistry, had begun making chemical mixtures on a kitchen stove; he was soon exiled to the garden shed. Then, in 1778, the year he set up home as a married man, he bought property in Cock Street with Benjamin for £270 from one William Tomlinson. In about 1790, further expansion came when he took on the copyhold of new premises and moved his entire business to a site closer to Benjamin’s activities, called (since at least 1675) The Brickhouse. He bought the four houses, two in Cock Street and two at the back adjoining 48 John’s Lane, from one John Fowler for £600. On 11 May 1791, he announced that he was ready for business at the new factory: John Mander, Chemist and Druggist, respectfully informs his friends, the Faculty and Public at large, that he has moved his warehouse and Elaboratory from King Street into Cock Street, where he humbly solicits a continuance of their favours, both wholesale and retail.

Among his many ventures, John diversified into making varnish, japans and colours, supplying the japanning trade in general, and by ‘horizontal integration’, the japanning materials at cost to his brother’s firm next door, Mander & Shepherd. The two brothers clearly worked closely together. An entry of 1794 shows: ‘Sept. 19th Payd Mr Mander, of Wolverhampton, for Paint, Oil, Turpentine, etc., etc., £2 8s. 6d.’ The growing business led to the formation of a succession of partnerships. First, in 1790, he took into partnership William Bacon, ‘a gentleman of fine business skills and considerable wealth’. Then John Weaver joined the firm in 1803. Weaver, who apparently came from Shropshire, ‘was a man of great energy and application to business’ and expanded the trade north into Lancashire and Yorkshire, and throughout the Midland counties. But he was a man of little sympathy: On one occasion it was reported to him that one of his employees had fallen down a hoist on the premises and been killed. He replied: ‘Ah! in the midst of life we are in death; is the cart loaded for Birmingham?’ John’s own son, also John, had no interest in the business, and joined the East India Company where he was a lieutenant and adjutant in their Invalid Corps at the time of his early death in Bombay in 1821. So in 1818 his nephew, Benjamin Parton Mander, by then aged 33, was induced to quit working with his father, Benjamin, and brother, after 15 years, and to join his uncle’s firm in Cock Street to secure the succession for the next generation. By that time, the capital in the firm of ‘Mander, Weaver and Mander’ amounted to £28,715. The Manders dropped out when Benjamin Parton died without heirs in 1835. Both John and Benjamin senior knew the business of the tin-plate workers, who provided the containers, ovens and surfaces for the bakers like Benjamin, which had to be coated with tin to avoid being affected by salt and sugar, and who were important customers for the chemicals supplied by John. We see all the early Midland trades at this date–japanning, tin-plate working, chemical and varnish manufacture, even to a degree baking and malting–as organically interdependent, and the family emerging with involvement in a variety of trades and ventures, maintaining the flexibility and the capital to move from one to the other. Among them, we find John Mander is recorded variously as a coal and ironmaster, apothecary, surgeon, druggist, a gas manufacturer, as well as being an investor in transport as a partner in the Wolverhampton Boat Co. in 1811. He was even making or commissioning ‘Staffordshire’ pottery at this time, which survives in the shape of a transfer ware soda jug with the ‘Mander & Weaver of Wolverhampton’ trade label, the first to give the foundation date of the business as 1773. This was to satisfy a European craze for soda water following Joseph Priestley’s experiments in dissolving carbon dioxide under pressure in water. The work of the japanner and tinplate worker, exemplified by his brother, Benjamin, was confined to tinning the sheets of iron and soldering them together, and then coating and decorating the finished object. He did not normally make the specialist materials which he applied, as a manufacturer of gums and resins. With the rapid growth of the metallurgical industries in the Midlands, John had seen a new market if he could successfully integrate the supply trades. It was a niche opening which he had the capital, specialized chemical knowledge and, as it turned out, the entrepreneurial skill to exploit. The Victoria County History states:

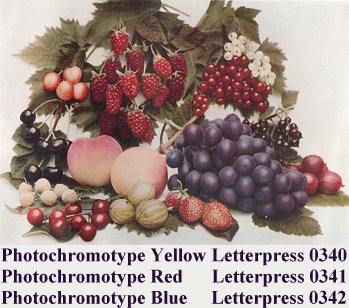

Midland industry was sustained by this second, less visible layer of ‘high-tech’ activity in the firms that manufactured the chemicals used in the production of its famous wares, and which gave them the distinctive finishes which help to brand and market them. Plain japanning, giving the metal or papier mâché a single-colour shiny surface, was a simple matter, but decoration in the debased rococo of chinoiserie and tortoiseshell demanded the use of an array of extravagant colours and pigments. These ‘chymists’ were subsidiary trades to the japanning and enamel industries, supplying and manufacturing not just the varnishes and japans for the developing local japanned ware trade, but increasingly the colours, the specialized gums and drying oils, the solvents and thinners, the gum elemi, the cinnabar, verdigris, orpiment and vermilion, used as colouring pigments by the artists. John Mander’s firm of ‘wholesale chemists’ prospered initially on the back of supplying the local trades. As it developed in complexity, size and product range, it became most successful as a manufacturing chemist, providing ‘choice chemicals’ for the London market; a term recalling that used in the company literature more recently, ‘speciality coatings’. It was one of the first to make calomel and the various mercury compounds employed in medicine, the arts and the chemicals industry. The firm was also one of the first to trade in chemicals with the United States of America and, according to a contemporary newspaper account, ‘had a large business with China and the East and West Indies, where their chemical preparations are held in high repute’. John Mander’s firm, trading by then as Mander, Weaver & Co., was also the first to manufacture gas in the town, to light their own factory and for chemical manufacturing processes requiring heat: the gas plant was still in use in the 1870s. Having gained knowledge of the new technology at a time when city fathers were clubbing together to supply gas to the growing manufacturing towns created by the industrial revolution, Benjamin Parton Mander was one of two of the firm’s partners listed among the 57 subscribers who formed ‘The Wolverhampton Gas Light Company’ by Act of Parliament on 22 June 1820, with a capital of £10,000 and the stated ambition of ‘the better lighting of the Town’. The enterprise was actively pursued during the summer and autumn of that year and, when two gasometers were ordered, the prospect of being able to offer gas in January 1821 ‘of the purest quality without smell or stain’ was no small attraction. A single giant iron column in fluted Doric, 40 feet high, known as the ‘big candlestick’, was erected in the middle of the main square at High Green, with a solitary light on top, ‘like a carthorse holding up a butterfly’, wrote a contemporary critic. But the conception was not an unqualified success, and it became ‘a lounging-place for the most notoriously vicious and dissolute characters of both sexes’. John Mander married (firstly) Esther Lea of Kidderminster in 1778 and lived in an ‘elegant villa’ at The Elms, Penn Road, known familiarly as Gallipot Hall, ‘an evident allusion to the trade carried on by its worthy owner’. He also accumulated considerable property in and around the family holdings at John Street. John’s public career tracked that of his brother, Benjamin. Like him, he was a Town Commissioner, taking the chair thirteen times at the early meetings between 1805 and 1825. He was among those behind the foundation of the first ‘Wolverhampton Library’ towards the end of 1794, with Benjamin, and was elected to serve on the Committee. It was a subscription library, a project of self improvement rather than philanthropy ‘for the mutual use and intellectual recreation of gentlemen’, the subscription being a guinea a year. He acted as vice president in 1813, but appears never to have been president. In 1818, he was landlord of the property (in Princess Street) which the Library occupied. As a Liberal in politics, in 1814 he was among those who petitioned Parliament to protest against England allowing France to carry on the trade in slaves for five years or more.

The Calvinist Charles Hunter with the Manders and their friends moved to worship in a little chapel in Grey Pea Walk (later Temple Street), where John and Benjamin both became deacons, and the births of Benjamin’s children were registered in the late Georgian generation (1781-91). Then in 1800 John bought a piece of land in Princess Street to build a bigger chapel. The Princess Street minute-book subsequently records: ‘Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Mander and Mr. John Mander sit down with us as occasional members, considering themselves members of the church at [Grey Pea Walk]’. By 1819 they were admitted ‘full and regular members’ there. Perhaps they had tired of attending the services of the minister, John Godwin, a censorious man and very eccentric. It is said ‘on good authority’ that the sacrament was never administered during his 30 years ministry, as he did not consider his congregation to be Christians. The Princess Street chapel had served its purpose well for twelve years when the premises were sold back to John for £400 to help finance a new Congregational chapel, while the old building became public offices where the town commissioners and the justices of the peace held their sessions. The new chapel was built in Queen Street in 1812, again on land which John secured as ‘a prominent and munificent supporter’. He retained the vaults below, which were let ‘to the scandal of the church’ to a ‘wine and brandy merchant’. One day some ‘wag’ posted the following verses on the cellar door:

Gerald Mander commented that these ribald lines … must have led to some head shakings in that strict and grave society. With what satisfaction must the Landlord, a regular attender in the chapel portion, have lent himself to his devotions secure in the knowledge that the basement was also paying its way! In later life, John became a fashionable and benevolent figure about town, involved in every aspect of its governance and especially in the proliferating nonconformist charities which became his métier. He was reputed to be the first to have a brougham carriage in Wolverhampton. By the time he died aged 73 in August 1827, the population of the town had grown to 23,000. He was a ‘Georgian tycoon’, writes Barty-King, who had established a durable mix of business, philanthropic and property interests, including ‘one of the largest chemical elaboratories in the kingdom’. He died leaving the then considerable sum of £16,000. He had drafted an eight-page will on 31 May 1827, leaving £2,000 to his second wife, Hannah (exclusive of the £1,000 left to her by her late husband), to be paid two years after his death. There was also an annuity. The £800 vested in trustees for his first wife, Esther, who had predeceased him, was transferred to his daughter, Amelia, who married a Chester wine merchant, John Williamson. He made detailed arrangements for the settling of his property all over Wolverhampton–in John Street, Queen Street, Princess Street and Can Lane. His obituary declared: He had been for about fifty years a prominent friend of religion and education, for which he was not only unsparingly munificent, but indefatigably active. Many a widow and her family have owed the comforts, and many young tradesmen their successes, to his intelligence and generosity. The institutions which he founded will be his best monument, and the tale of the grateful his best panegyric. His end was worthy of his life. John was a capitalist entrepreneur first on the periphery of the great new scientific and politico-religious ideas fermenting in the West Midlands. His father, Thomas, had been born into a rural and agricultural society still recognisable as Shakespeare’s Warwickshire. By the time of his death in 1827, John was contributing to an urban and industrial economy based on new applications for science in manufacturing technology and new structures of economic organisation which had caused a transformation in England and were fast converting her Midland towns into the premier workshop of the world. Through the enterprise of brothers Benjamin and John, the Mander family was set up as a mercantile dynasty in Wolverhampton, whose fortunes were founded on the mix of businesses which continued to bear their name for over two centuries. The brothers had defined the family in the new, guiding political culture of Low Church, Calvinistic Protestantism which had triumphed in Anglo-America: commercially adept, militantly expansionist, firmly convinced that it represented a chosen people and a manifest destiny.

|