|

A Successful Trial

A very successful trial of an electric tram

motor was made yesterday afternoon (Friday, 1st June, 1888) on

the tram line between Sydney and Botany. The system of which the

capabilities were demonstrated is that patented by M. Julien,

the right of using which in Australia and New Zealand has been

purchased by Mr. E. Pritchard, who is well known in connection

with the construction of the main trunk sewer to Bondi, as well

as in relation to railway works.

The trial was witnessed by between 200 and

300 gentlemen, who were conveyed to and from Botany by a special

tram. Amongst the spectators were Mr. W. Clarke, Minister of

Justice; Mr. Cowdery, Engineer for Existing Lines; Mr. E. C.

Cracknell, Superintendent of Telegraphs, and a very large number

of members of both branches of the Legislature. The vehicle used

was one specially constructed at the establishment of Elwell-Parker,

the electrical engineers, in Wolverhampton, England, and it was

built in accordance with the principle laid down by the inventor

of the system exhibited.

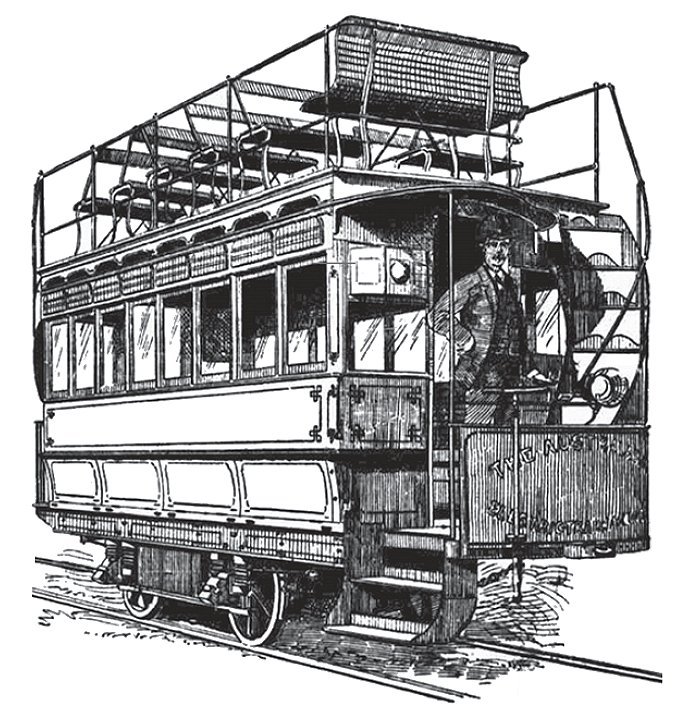

The vehicle resembled in appearance an

unusually large omnibus, and reminded those who have visited

Adelaide of the tramcars used in that city. The car, which is a

car and motor combined, was of a larger pattern than those

employed at Rio Janeiro, New York, Philadelphia, and Brussels,

in all of which cities the Julien system is in operation. In

those cities the cars used seat 35 persons, whereas that shown

yesterday seats 50 persons, 26 on the upper deck (which is

uncovered), and 24 inside.

Undue haste had been shown in the

construction of the car and the consequence was that it did not

present that finished appearance looked for in regard to new

vehicles, and some defects had arisen in course of construction

which contributed to make the trial a very severe one. One fault

which was very noticeable was the unnecessarily substantial

character of the car, which was much stronger and much heavier

than was absolutely necessary. The car was said to be heavier

comparatively than those now used in connection with steam

traction. It weighs when empty 5 tons, and when full from 8¼ to

9 tons.

The motive-power is stored in lockers,

situated underneath the seats, and access is gained to these by

hinged panels over the wheels. The motor consists of 8 trays of

accumulators, each tray holding 15 cells. One charging of the

car is sufficient for 80 miles or 7 hours actual running, and a

similar time is occupied in storing a fresh supply of

electricity. The storage of electricity is accomplished in a

shed in which are employed a 10 hp. boiler and engine and one of

the Elwell-Parker dynamos. To take out the exhausted cells and

substitute newly charged ones occupies only about five minutes.

The electric tram-motor seen yesterday is designated a 20 hp.

motor.

When in perfect working order, and that was

not claimed to have been the case yesterday, it is capable of

running at a rate of about 15 miles an hour. The maximum reached

yesterday was about 10 miles per hour. The car is capable of

running up a gradient of 1 in 10, but it is not considered

desirable to run it on a steeper gradient than 1 in 15.

The car was at Botany and taken on several

spins by the electrical engineer, Mr. Bullimore, who pointed out

to the passengers various peculiarities in construction, and

showed that he had an intimate acquaintance not only with the

electrical but with all the other systems of tramways; so much

so that he was able to point out the various respects in which

other systems failed to come up to the requirements of a perfect

tramway service.

A strong case was made out in favour of the

Julien system, on the ground that it could be applied to almost

any description of car, and especially those in use on the

Sydney tramways, that it would put an end to shrieking whistles,

abolish all smoke and smut, and enable the car to which it was

applied to travel almost noiselessly.

After several spins had been taken with the

car at Botany it was duly freighted, and sped off to the city on

the Government tramline. This route is said to afford the most

severe test that could possibly be applied to any tram

conveyance, and those of the citizens who remember incidents

which frequently happened in connection with the establishment

of the tram system between the city and Botany will not be

inclined to deny that that line affords more than one severe

test. The gradient from Liverpool Street to Belmore Park is 1 in

18, and is said to be the steepest on the whole of the Sydney

tramways. The Barrackhill at Paddington is generally regarded as

one of the most difficult for a tram to surmount, but that is

only 1 in 22. In running from the terminus at Botany to King

Street in Sydney, the electric motor occupied 35 minutes, and

the journey was not only a novel but a very pleasant one.

A noteworthy improvement that would be

effected by the general adoption of some such car as that used

yesterday would be in respect to the seating of the passengers.

In the cars now in use, passengers who may sit vis-à-vis are

almost of necessity brought so close to each other as to produce

anything but a pleasant sensation. In the vehicle used yesterday

the seats are placed longitudinally, and a sufficient space

intervenes to allow of a conductor passing along the centre of

the car without incommoding the passengers.

The question of the cost of working was

discussed, but no definite information was forthcoming upon this

point, beyond the fact that in England it had been found to be

equal to about 6d. per tram mile. Manual labour is used in

connection with the recharging of the cells, and to the English

estimate of 6d. per tram mile would have to be added the

difference in the value of labour as between England and New

South Wales.

There were only two weaknesses noticed at

yesterday’s trial, and these would have escaped observation had

it not been for the presence of some gentlemen whose special

training in electrical science had led them to look for a

perfect electrical machine. Both of these weaknesses, it was

pointed out, are capable of improvement. One was the large

amount of care seemingly required to always ensure a speedy

application of the brake, and the other was a slight grating

noise, resembling the escape of steam, and at the same time

suggestive of the sound caused by the application of a brake to

a heavy vehicle descending a steep incline, the first fault is

susceptible of improvement, so that the car can be brought to a

stand within its own length, and the second can be remedied by

the substitution of an electrical brake for the ordinary chain

brake now in use.

Whilst the car was under examination at

Botany, refreshments were partaken of. A little later Mr. O. R.

Dibbs, M.L.A., referred to the enterprise shown by Mr.

Pritchard, and the gratification which the visitors had

experienced at inspecting the vehicle. He felt convinced that

electricity was the motor of the future. He was sure that the

visitors thanked Mr. Pritchard for the entertainment he had

given them. At the call of Mr. Dibbs, three cheers were given

for Mr. Pritchard. The compliment was duly acknowledged. |