|

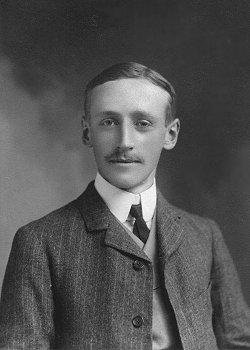

Sir Geoffrey Mander |

Sir Geoffrey Le Mesurier Mander (1882-1962)1

was a Midland industrialist, an art collector and impassioned

parliamentarian, the Liberal specialist on foreign policy

between the wars. From a nonconformist and radical background,

he held a strong patrician sense of public service and

philanthropy. As a politician he was a man of integrity, ahead

of his time, who spoke up as an anti-Appeaser and a crusader for

the League of Nations between the wars. He made a reputation as

an oppositionist, for his determined use of parliamentary

questions; a gadfly who never spared to wing into the attack

whenever sloppy thinking and deceit threatened to obscure the

issues of the day. He represented Wolverhampton East from May

1929 to the fateful 1945 landslide.

Geoffrey Mander came from a strong liberal tradition. The

Mander family were in the vanguard of the industrial revolution

in the

Midlands.2

|

| From 1773 they established in Wolverhampton a

durable cluster of businesses as manufacturers of chemicals,

gas, japanware and (mostly successfully) varnish, paint and

printing ink. By 1815 they were varnish manufacturers by

appointment to Queen Charlotte. By 1827 they already operated

'one of the largest chemical elaboratories in the kingdom',

trading from China and the East Indies to the Americas. As the

business prospered with the industrial revolution, they became

established as the varnish kings of the Empire, and were given

the means and leisure to become active and progressive

philanthropists.

In the early nineteenth century, they campaigned against the slave

trade, lobbied for the reform of the criminal code, and set up a union

mill to provide cheap flour and bread in the difficult aftermath of the

Napoleonic wars. Four Manders at the same time were Town Commissioners

in Georgian Wolverhampton. They pursued a 22-year chancery suit for the

protection of non-conformist chapels and endowments, a test case which

was heard by the lord chancellor Eldon and was to lead to an act of

Parliament by 1844. In 1817, Charles Mander rode to London to petition

the home secretary, Sidmouth, for the reprieve of two innocent soldiers

condemned to death for stealing a shilling coin. It was a romantic

incident which appealed to the imagination of contemporaries and became

the inspiration of a forgotten Methodist novel by Samuel Warren.3

It led with the help of Samuel Romilly in Parliament (the Manders' first

counsel in their litigation) to the repeal of the Blood Money Act

(1818), 'one of the worst acts ever to disgrace the Statute Book'. The

family founded chapels, fountains, free libraries and schools, and

became progressive mayors, filling nearly every public office in the

county. Geoffrey's younger brother, the Hollywood actor and novelist

Miles Mander (who married an Indian princess), summarized the background

writing 'to [his] son in confidence' (1934): |

|

The Manders have nobly vindicated themselves. At the time of writing,

they have produced one baronet, one Member of Parliament, High Sheriffs,

Deputy Lieutenants and several of the lesser municipal dignitaries such

as Mayors, Magistrates and Councillors. In fact, we are quite obviously

worthy people… Your Canadian great-grandfather was in the Ottawa

Parliament, your grandfather, Theodore, was one of the most prominent

Liberals of his day, your Uncle Geoffrey is at present a Liberal Member,

and I am hoping to be in the House shortly myself.4 |

Geoffrey Mander was the eldest son of Theodore Mander (1853-1900), a

Gladstonian Liberal and strict Congregationalist. Theodore married Flora

Paint, a Canadian from Nova Scotia of Guernsey extraction (from whose

forebears Geoffrey derived his second name), whose father was himself,

as Miles states, MP for Richmond county in the Dominion Parliament in

the 1880s. Theodore was a man of refined tastes and sympathies, a

collection of whose diaries and letters was published in 1993 as

A Very Private Heritage.5

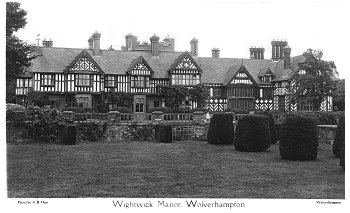

He is remembered today as the builder of Wightwick Manor (1887-93), a

half-timbered aesthetic house of exquisite craftsmanship and detailing,

with outstanding William Morris furnishings and pre-Raphaelite

collections.

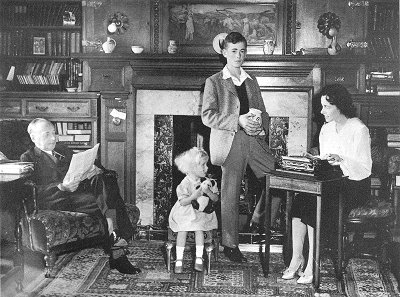

A family group at

Wightwick in about 1898. Left to Right:

Marjorie, Theodore, Lionel, Flora, Alan, Geoffrey. |

Theodore in own his day was known as a Liberal and philanthropist. As a

young man, he was active in public life in the arts and education, as a

governor of the Grammar School, of Tettenhall College and of Birmingham

University (where he endowed a scholarship), a member of the Royal

Commission of the British Section of the Paris Exhibition and one of the

founding benefactors of Mansfield College, Oxford, which was the first

nonconformist college in the University. He described Henry Fowler,

first viscount Wolverhampton, as 'his political mentor', chairing his

election committee. In June 1895, he was offered the Mid-Worcester seat

in Parliament. William Woodings of The Midland Liberal Federation wrote

to him: 'Your name would be well known and you have almost a local

connection… The constituency is Liberal in tendency and is not difficult

to work.' He was still committed to municipal affairs, and didn't live

long enough to contest the seat. He was a successful mayor of

Wolverhampton at the turn of the century, he was presented to Queen

Victoria and entertained the Duke and Duchess of York at Wightwick. But

he died in office a few months later, in 1901, following an operation on

his kitchen table. He was aged just 47.

|

|

Geoffrey was 16, and still at Harrow at the time of his father's death.

His mother Flora died soon after, in 1905, leaving him to assume the

responsibilities of his father's estate early. He was a prickly,

cross-grained youth, described by the paterfamilias, his father's

cousin, the staunch Tory Sir Charles Tertius Mander, as

'an impossible young cub… It is time we brought him up with a round

turn… he is very self opinionated, has no judgment or tact & is much too

big for his boots, & has been ever since his father died.' |

Wightwick Manor - The main entrance. |

He went up to Trinity, Cambridge, where he followed family tradition by

reading Natural Sciences. At Cambridge, he soon continued in the mould

of public service, now with a radical slant. He joined the Union and the

University Liberal League, and

'a thing called the Cambridge University Association for promoting

Social Settlements. I have not the remotest idea what it's about, but I

hope it's not socialism'. He founded a dining and debating club

called 'The Dabblers'. Stephen Ponder writes:

|

From an early age he had a strong sense of social responsibility and

interest in public life… He was typical of a particular sort of English

radical, a man of wealth and position who devoted himself to public

service, supporting and proposing measures at odds with his background

and private interests.6 |

Like most members of the family, he became a magistrate, in his case at

the age of 24, and in due course Chairman of the Bench, serving for 50

years. By the time of the Kingswinford by-election in 1905, the press is

describing him as 'a Liberal member of a distinguished local

Conservative family'. He supported the Labour candidate for West

Wolverhampton in the 1906 election against a family friend, Sir Alfred

Hickman. He wrote later:

'My action caused great indignation in Conservative circles in the

neighbourhood and I found myself cut in the hunting field by some of

them.' His second wife Rosalie described how, like many radicals who

refused to conform to the conventions of the 'County' pattern, he was

looked upon askance by many families. This attitude only changed after

the second world war, 'both because party bitterness in general had died

out and because Geoffrey Mander's sincerity and his devotion to the

causes in which he believed won respect all round':

|

A tolerant 'man of goodwill' himself, who never spoke or acted out of

malice or spite, he was glad of this development and appreciated being

invited to social functions in the neighbourhood-more perhaps than he

enjoyed attending them. |

He cut his teeth as a Liberal member of the Wolverhampton Borough

Council (1911-20). He shocked the Councillors, showing a foretaste of

later interests, when he proposed a minimum wage of 23s. for all

municipal employees. He came out in favour of his cousin Gerald's

campaign to save the Old Deanery, an historic landmark in Wolverhampton

attributed to Christopher Wren. This initiative was frustrated by the

onset of war and the building where Dickens is said to have stayed was

demolished in 1921.

|

The visit of Henry Nicholas Paint, M.P. to

Wightwick. |

He was High Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1921. He again created a stir

when he proposed a woman as his successor, Lady Joan Legge, daughter of

Lord Dartmouth. The Privy Council wrote to her father to inquire whether

she had the necessary property qualifications, and she was not

appointed. But he did secure the selection of the first woman to serve

on the grand jury, Mrs Kempthorne, the wife of the bishop of Lichfield.

He stood unsuccessfully as a Liberal candidate for the

Midland constituencies of Leominster in 1920 and then

Cannock and Stourbridge. In 1929 he finally realized his

early ambition by entering Parliament as Liberal MP for East

Wolverhampton, a seat which had been represented by Liberals

continuously since the Reform Bill of 1832. It included only

three wards of inner Wolverhampton itself (as opposed to

eight in Wolverhampton West), with urban districts and a

cluster of independent surrounding villages. It was an area

where Mander Brothers was dominant, with factories in both

Heath Town and Wednesfield, and many employees of his works

among the voters.

He was active in the Liberal Party organisation from the

early 1920s, as a member of the executive committee of the

National Liberal Federation and a frequent speaker at party

Assemblies. He made a reputation as a parliamentarian by his

skilful use of 'awkward' Parliamentary Questions, cornering

the government of the day with his determined invigilation.

The journalist Percy Cater recorded his memories of:

|

the pinkly pugnacious Mr. Mander waving above the battle of

question-time like the banner of some cause or another, accompanied by

orchestral splurges of derisive laughter or 'Sit down'… one of the

hornets or gadflies who animate the political scene, infuriating the

stung and keeping the unstung in a lively state of tension. Baldwin once

said, in one of those shrewd epigrams which come from him as easily as

blowing the smoke from his pipe, that Mr. Mander would 'tread honestly

and conscientiously on every corn from China to Peru.'

Mr. Mander … is not pompous. A mild and benevolent eye

darts from sandy brows in a face which is conspicuously

equable and good humoured. He is a good, if not a great man.

He is a sort of pocket edition of noble indignation. See him

pouncing up to ask a question. There you see fire, purpose,

an inextinguishable soul.

No good a Baldwin bobbing up and answering Mr. Mander

briefly and completely, 'No, sir,' and rousing shocking

laughter. No good a Chamberlain using the iron hand from

Birmingham. Sharp as a game-cock and as perky, Mr. Mander

dashes in for some more of the fight.

|

|

| The Old Manor

House at Wightwick from Wightwick Manor tower. |

|

His special interests in Parliament were industrial relations, on which

he spoke with authority and sympathy as a manufacturer through the

Depression, and foreign affairs. Geoffrey became the Liberal expert on

international relations, peace and disarmament, between the wars and the

most ardent defender of the League of Nations system of collective

security; 'the most persistent speaker and questioner on foreign affairs

in the 1930s and altogether a zealot for the League'.7 |

He was one of the first to foresee the consequences of not taking a firm

stand against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Into a House

of Commons debate mainly devoted to currency, commerce, industry and

tariffs, typically he intruded Manchuria and put forward the League

position:

|

It is a test question. We have to decide whether war is to be permitted…

We have the whole of the League plus America on the one side and Japan

on the other. [I hope the Council for the League would] use all the

moral force they possibly can… and if that were not enough use financial

and economic pressure and, if that will not do, use pressure in the way

of a blockade in preventing goods from going into or coming out of

Japan… We have to take a bold and courageous view and, without using any

physical force-that will not be necessary-mobilise all the different

methods of economic, financial and moral pressure which are available to

force Japan to realise that war is not going to be permitted to break

out again… There is no doubt that, if we fail in this issue, we are

abandoning all the hope that arose out of the war, and the sacrifice of

a million Englishmen, to say nothing of nine million others, who gave

their lives for a great ideal will very largely have been in vain.' 8 |

As war again threatened again in the Thirties, he was one of the first

to speak out against the Dictators. He tabled the International Economic

Sanctions (Enabling) Bill of 17 May 1933, which made him 'one of the

first to call attention to the German danger publicly in Parliament and

at the same time make definite proposals for dealing with it';

supporters included Sir Austen Chamberlain whose 'death in 1937 was a

heavy blow to peace'. The Peace Bill of 23 May 1935 (and subsequently)

incorporated machinery embodied in the Covenant of the League of Nations

for the settlement of international disputes, and was supported by

Harold Macmillan, P. Noel-Baker, Sir Richard Acland and Lovat Fraser,

inter alia.

In the 1935 General Election his comfortable victory against the Labour

and Conservative opposition bucked the trend when the Liberals won only

two other urban seats where they faced competition from both the other

parties. He became a vehement, articulate critic of Neville

Chamberlain's policy of Appeasement, and his 'inability to see what was

going on in the world', an ally of Churchill, Eden and Sinclair, whose

polemical jabs were a wake-up call against a deep-rooted national will

to self-deception. He said that it would remain

'one of the regrets of my life that I did not make some sort of

speech … when Mr. Chamberlain announced his intention of flying to

Munich… If the Debate had been kept up, the spell would have been

broken… Others would have followed and the dangers inherent in what was

happening would have been exposed.'

His polemic was set forth in his book, We were not all Wrong (1941),

arguing that many people and parties foresaw the disaster to which

errors of policy in dealing with 'the Nazi menace' in the 1930s would

inevitably lead:

|

Municheers should never again be allowed to control our destinies. It is

too ghastly to think of the same unimaginative, isolationist, naïve,

complacent attitude, however well meant, being adopted after the war.

Absolute national sovereignty has outlived its usefulness in the world

in which we now live, just as has the Divine Right of Kings internally.

Old loyalties, deep-rooted, historic and admirable, remain… It is our

responsibility as it is in our power in the great adventure we must

lead: England cannot afford to be little, she must be what she is-or

nothing.10 |

A generation later, his son, John Mander, a political journalist and

cultural critic, described the origins of Appeasement. Ironically, he

wrote, in its intellectual perspective it was largely the creation of

liberals of nonconformist background like his father:

|

Evidently … the roots of Appeasement lie deep: they lie in the English

penchant for wishful thinking, they lie in the English easy-goingness

and tolerance, they lie in that insularity which for the greatest part

of our history has been our greatest boon, but which, over the past

century has proved, arguably, our greatest curse.11 |

When Geoffrey spoke up in the House of Commons in support of sanctions

against Italy after the invasion of Abyssinia, Mussolini fired off a

personal diatribe against him in his paper, the

Popolo d'Italia. In 1938, in a climate of international tension,

il duce took reprisals against the Milan branch of 'Fratelli

Mander' and asked customers to boycott their goods.

A fine summer evening's view of Wightwick

Manor from

the rear garden. |

He was far sighted in many of his peace campaigns. He was one of a

handful of MPs who inveighed against Hitler's territorial ambitions in

the Ukraine in 1935. As war broke out in 1939, he pleaded the Jewish

cause, telling Parliament in July that Government immigration policy was

leaving Jews with no escape from Germany 'other than by illegal

immigration into Palestine'. In April 1941, he wrote in the Jewish

Standard: 'The cause of the Jews throughout the world is the cause for

which Great Britain and her allies are fighting'.

| Princess

Sudhira Mander, who married Alan, Geoffrey's

brother. |

|

|

During the war, when the Liberals were asked to join the government

coalition under Churchill, Geoffrey became Parliamentary Private

Secretary (1942-5) to their leader, Sir Archibald Sinclair (later Lord

Thurso), the Minister for Air.12

Mander Brothers' Heath Town works was marked with a red ring on a

Luftwaffe plan, found after the war, as

'Chemikalien', indicated as a strategic target for bombing. He

rescued various bomb-damaged fragments of the House of Commons from the

Blitz, installing two stone crowns from the pinnacles of Big Ben as

ornaments about the garden at Wightwick. He kept the archives of the

League of Nations Union when they were forced by financial difficulties

to move to smaller premises in the early 1940s.

Wolverhampton East was one of the last urban constituencies that the

Liberals managed to hold against both Labour and Conservative opposition

up to 1945. But he lost his seat in the Labour landslide of that the

1945 General Election and was knighted in the same year (K.B.). His was

a great loss to Parliament. |

Thurso regretted the 'massacre' of so many 'able, experienced and

popular' candidates as he.13

There was a rumour for a time of his being given a peerage, and the

Press proposed he be gazetted with the equivocal title 'Lord Meander',

in commemoration of his tireless crusades and pertinacious questions,

seamless diatribes and string of private member's bills in the House.

|

In 1948 he joined the Labour Party, arguing that it had become the

logical successor of the Liberal tradition in his pamphlet

To Liberals, written for the Labour Party in 1950. In due course

he became a Labour member of the County Council. To many members of a

family whose traditions stretched to radical Whiggery, this was beyond

the pale. But he did say privately, that if he had not lost his seat, he

would have remained a Liberal, and most likely have been appointed chief

whip of the Liberals in Parliament.

Geoffrey Mander the politician was not quite forgotten by an

older generation. The first question Rab Butler asked me when I

followed Cousin Geoffrey to Trinity, Cambridge was, 'How are you

related to that b***er, Geoffrey?'14

My own memories are of a fusty, Edwardian patriarch, small in

stature, with a watch chain, who called in after church with his

political friends like Clem Attlee. Apart from his public

service in politics, his liberalism is vividly exemplified in

his career as an industrialist and an art patron. |

Geoffrey Mander admiring the

Morris 'bird' pattern curtains with the Attlees. |

|

The family company, Mander Brothers, was known between the wars as a

model company. Geoffrey, as the eldest of his generation, was chairman,

while his cousin, Charles Arthur (the second baronet), was managing

director. Sir Charles was 'wet' as a Tory, active in local government

and Midland affairs, and deeply interested in everything that touched

the human side of industry. In Parliament Geoffrey had pushed through

the Joint Industrial Councils and Work Councils Bills. Together they

implemented typically progressive initiatives in industrial welfare, to

foster peace in industry. These included a joint works' council

providing a workable system of joint consultation (1920), a welfare club

(1920), profit-sharing schemes for employees, holiday schemes,

suggestion schemes (1925), works pensions (1928), a house magazine,

staff pensions (1935), and a 'contributory co-partnership scheme'

setting aside shares for employees, with provisions to pay for shares by

instalments.

Most notably, Manders was the first company in the country to introduce

the forty-hour week. The historic agreement, the first of its kind in

Britain, was brokered and signed by Ernest Bevin, general secretary of

the Transport and General Workers' Union, in September 1932. 'Bevin was

very proud of signing that agreement', said Geoffrey later: 'He used

often to refer to it when were both in the House of Commons.' The press

wrote: 'In the history of industrial welfare, Manders may claim a high

place', where welfare had been 'part and parcel of the outlook of

Manders as employers almost since the company's foundation in [1773]'.

Geoffrey was reported summarizing:

|

My ancestors were very religious people. They always used to open the

day's work with prayers and lead hymn-singing at the end of the day.

Those religious principles which coloured their dealings with the then

small number of workpeople were the forerunners of welfare principles as

we know them today. In the history of industrial welfare Manders may lay

claim to a great deal of pioneering work. |

|

|

Wightwick: postcard from Geoffrey Mander, 1932

|

As an art patron Geoffrey's contributions to Wightwick Manor have been

his most secure legacy. When his father died young, much at Wightwick

was left undone. But the sequel has been fortunate, for Wightwick is the

creation of two generations. Geoffrey's was a man of vision and ability

whose own contribution was decisive, and shows evolving attitudes at

work in the interpretation of the nineteenth century. |

| His taste was decisive in creating the

ensemble we see today; improving and deepening the

collections, but also the garden. One of his first acts was

in 1910, when, still in his twenties, he was already

commissioning Thomas Mawson to design the garden terrace on

the south side of the house.

He married first in 1906, Florence Caverhill, a Canadian like his

mother. His second marriage in 1930 was to Rosalie Glynn Grylls

(1905-1988).16 She was an early

female graduate of Oxford; elegant, intellectual and talented. Elizabeth

Longford was one of the last to remember this exceptional 'Cornish' girl

at Lady Margaret Hall reading Modern Greats, 'brown eyed, dark haired,

with teeth really like pearls … who went on from strength to strength'.

She described her as amusing and amused, full of anecdotes, a vivacious

speaker, quick thinking and always exquisitely dressed; she was also

'the last of the militant atheists'. Her husband, Frank, who took

schools on the desk beside her, was taken by 'the exceptionally pretty

young girl whose arrival was always heralded by the tap of elegant

shoes'.

|

Like Geoffrey, Rosalie also entered politics, as a prospective Liberal

candidate for Reading, when the Party was enjoying a revival. She was

nearly 20 years younger than he, of course, and was secretary to the

Liberal MP, Edgar Granville. Before the time came for her to face the

electors, she married him in the crypt of the House of Commons. She was

eyed with suspicion as a bluestocking in the wider family. She soon

became known to them, who tended to pious disapproval of divorce and

remained wary of radical politics, as 'The Secretary'. |

Geoffrey and his family.

Children Anthea and John are in the centre, and

Rosalie his wife, the Victorian biographer, is on

the right. |

Rosalie never lost her interest in progressive politics. However, she

went on to pursue her literary interests as a highly-regarded

biographer, lecturer and scholar, particularly of the Shelley/ Godwin

circle and the 'Pre-Raphaeladies'. With her knowledge and encouragement,

Geoffrey began in the 1930s to develop and extend the collections at

Wightwick and they became pioneers and authorities in the overdue

re-assessment of Victorian art. They were among the first collectors to

take a serious interest in the art and literary manuscripts associated

with this late Romantic flowering, coming to know the survivors and

successors of the circle of artists, designers and writers themselves.

Many of them now visited Wightwick, like May Morris in 1938, or

contributed to the collection, like Helen Rossetti Angeli, daughter of

W.M. Rossetti and Lucy Maddox Brown, enriching its associations. They

fostered links with the romantic Utopian socialism preached by William

Morris, and many of the radical politicians and thinkers of the day

visited what became a Midland political fortress.

In December 1937 the future of house and collection was finally secured

when Geoffrey presented it to the National Trust, with an endowment of

20,000 Manders shares. He was encouraged by the Trevelyans ('of another

Liberal and eccentric family', wrote Rosalie, who gave Wallington to the

Trust shortly afterwards) and Professor W.G. Constable.17

Rosalie Mander wrote: 'He never regretted it, for he liked to think

that the public should enjoy what had been his private property.'18

He delighted in showing visitors round the house, and insisted on

keeping no quarters barred from public view; his dressing room and

bathroom included.

Geoffrey had installed a squash court in 1928 and continued to play

tennis there until just shortly before he died aged nearly eighty in

1962. Lord Longford (then Frank Pakenham) wrote in his Times obituary

that he was an 'issue man':

There was never a more selfless politician… Perhaps he should not be

thought of as a politician at all, for all his love of the House of

Commons and the political life. He was supremely a man of causes.

Abyssinia, Czechoslovakia, anti-Fascism, Collective Security-he preached

them indefatigably and inflexibly, though with unfailing good humour,

and what he preached he practised.

He was the most modest of men and would have disclaimed the slightest

comparison with Lord Cecil; yet even Lord Cecil did not embody more

completely the idealism of the League of Nations and all it stood for.

His horror of the whole policy of appeasement culminating in Munich led

him to harry the Government with an endless stream of questions in the

House of Commons, to the irritation of his opponents and the admiration

of his friends.

In all the developments leading up to the establishment of the United

Nations and throughout the years that followed, his staunchness and

energy in the struggle for peace never flagged. It was the greatest of

pities that he was without a seat in either House during the post-war

years. But whether in his own Midlands or in the national and

international politics he continued to find ways of rendering service

that counted.

|

References

|

1. |

The fullest account is a booklet life, prepared by his widow mainly for sale

at Wightwick: R.G.G. Mander, Geoffrey le Mesurier Mander (1882-1962),

Donor of the house, Oxford [n.d.]. He left an autobiographical fragment

(1924-57), in the National Liberal Association archives at Bristol

University Library (DM668). |

|

2. |

For an account, see Geoffrey Mander

(ed.), The History of Mander Brothers [1955] and the

author's own

Varnished Leaves: a biography of the Mander

family of Wolverhampton, 2004 (with bibliography). |

|

3. |

Now and Then, 1848. |

|

4. |

Miles Mander, To my Son-in Confidence, Faber, 1934. Lionel ('Miles')

and his brother Alan both married daughters of the Maharajah of Cooch Behar.

(see Sunitee Devee, Maharani of Cooch Behar, The Autobiography of an Indian

Princess, 1921, pp. 43, 203-4.) |

|

5. |

Pegg, Patricia (ed.), A Very

Private Heritage: The Family Papers of Samuel

Theodore Mander of Wolverhampton, 1853-1900,

Malvern: Images Publishing, 1996. |

|

6. |

Wightwick Manor, National Trust guide, 1993. |

|

7. |

R.A.C. Parker, Chamberlain and

Appeasement, 1993, pp. 40, 52 and 54. |

|

8. |

259 HC Deb 5s, cols 1189, 45, 60, 201-2; Parker, pp. 40-1. |

|

9. |

Geoffrey Mander, We were not all Wrong, 19381941, pp. 87-9. |

|

10. |

We were not all wrong, p. 118. |

|

11. |

John Mander, Our German Cousins, 1974, p. 247. |

|

12. |

Archibald Sinclair (1890-1970), first Viscount Thurso (1951). |

|

13. |

G.J. de Groot, Liberal Crusader:

The Life of Sir Archibald Sinclair, 1993, p.

227. |

|

14. |

The answer, like a four-move chess problem, is that I am his first and second

cousin, twice removed. |

|

15. |

The agreement is quoted verbatim in The History of Mander Brothers.

See also Mander Brothers Ltd.,

An Account of the Internal Organisation of the

Business of Mander Brothers, Ltd., Wolverhampton, In its relationship to the

Employee (Approved by the Joint Works Committee), 1925, revised 1934,

1939, 24 p. |

|

16. |

See obituaries in The Times (4 Nov. 1988); The Daily Telegraph

(in part by Elizabeth Longford, 4 Nov. 1988); and Martin Drury (National

Trust Magazine, Summer 1989). |

|

17. |

Director of the Courtauld Institute, London, and Slade Professor of Fine Art

at Cambridge. Another kindred spirit in the League of Nations, connected

(distantly) by marriage through the Turnbull family, was Roger, ninth Lord

Stamford; the tenth Earl presented Dunham Massey to the National Trust in

1976. |

|

18. |

The Country House Remembered, edited by M. Waterson,

1985. |

|

19. |

J. Orbach, Victorian Architecture in Britain, 1987, p. 440; Martin

Drury, 'Address to the 1999 AGM', Historic House, Spring 2000, p.

13. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|

|