|

In the first half of the 19th century, town gas,

initially for street lighting, was in great demand. Gas

pipes were originally hand-wrought in short lengths that

were expensive and slow to produce. This all changed

thanks to Cornelius Whitehouse, who invented a quick,

accurate and reliable method of cheaply producing tubes

that could cope with higher pressures. His work

revolutionised the tube-making industry. Widespread gas

distribution now became a practicality, but

unfortunately he received little in the way of financial

reward, for his efforts.

Luckily for us, Frederick William Hackwood, Wednesbury's

late19th century historian, wrote several articles

chronicling Whitehouse's life. This short version is

based on his article in the 1898 Ryders Annual, and his

"Wednesbury Workshops" from 1889.

Cornelius Whitehouse was born in Oldbury on 22nd July,

1795. His father Edward became an expert sword maker,

producing high quality swords at a time of high demand

during the Napoleonic Wars. One day his products were

inspected by a corrupt War Office inspector who said

they were not up to standard. Edward lost his temper

with the man and forced him to hold an approved sword at

arm's length. He then cut the sword in two with a single

blow from one of his own swords. From then on they were

Government approved.

Cornelius and his brother worked for their father in his

Birmingham workshop and became expert sword makers and

gunsmiths in their own right. Cornelius became a

recognised craftsman and was offered a job as a

Government sword inspector, but turned it down.

After the Napoleonic Wars the demand for guns and swords

fell and so the family moved to Wyrley where they worked

for Gilpin, the edge tool maker. Four years later

Cornelius moved to Wednesbury Forge to work for Edward

Elwell making edge tools.

Cornelius Whitehouse.

While working at the forge his thoughts turned to tubes,

and he began experimenting with new ways of producing

them. At the time there was a great demand for gas

pipes, which were made by an expensive and labour

intensive process requiring very skilled workmen. Tubes

were formed from an iron strip, or skelp, which was

heated in small sections, a few inches at a time, in a

conventional open hearth forge. After hammering each

section into shape, each side of the seam was overlapped

and hammered to form a weld. Many heatings were required

for each length of tube which had a maximum length of 4

feet. The industry couldn’t keep up with the demand and

so there was a lot of interest in increasing

productivity and also reducing the manufacturing costs.

Cornelius's solution, developed in 1824 and 1825

consisted of heating the whole strip in one go, in a

hollow fire of the type used by the edge tool makers at

the forge. The strip was then shaped and welded in one

operation by drawing it out of the furnace by a chain

attached to a drawer bench, and passed through a pair of

semi-circular dies. The process produced an accurately

shaped tube with smooth inside and outside surfaces. It

is believed that he first offered it to Edward Elwell

who suggested that he should take it to James Russell.

With Russell's help he took out a patent for the process

which was granted on 26th February, 1825.

A drawing based on the 1825

patent.

Russell agreed to employ Whitehouse and pay him the sum

of £25 annually for 14 years, the life of the patent. He

soon increased the sum to £50 when Whitehouse assigned

the patent rights to him.

The new tubes were twice as long and half the price of

the older ones, and could withstand a higher pressure.

Russell built a new factory at a cost of £14,000 and

invented a way of screwing tubes together.

|

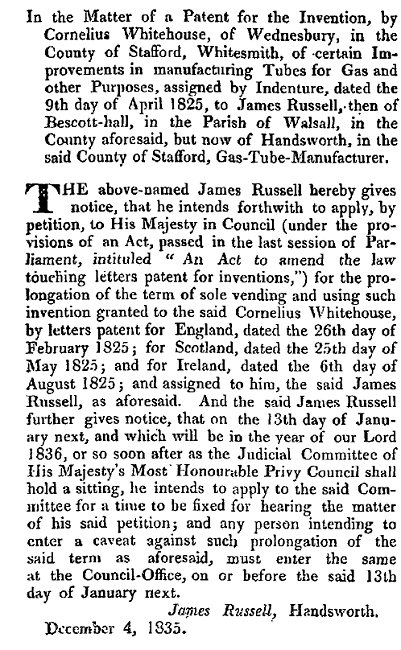

From the London

Gazette, 11th December, 1835. |

Large numbers of tubes were produced, but success came

at a price. From 1830 until 1845 Russell was constantly

in litigation with rival manufacturers who tried to

infringe his patent. By 1838 the legal expenses amounted

to approximately £4,000.

The new revolutionary process was seen as a threat by

the traditional tube makers and Russell and Whitehouse

went in fear of their lives. On one occasion Whitehouse

even shot at the legs of a gang of men who were about to

attack his house.

In 1842 he took out a patent for an improved process

with one of Russell's sons; Thomas Henry Russell.

Unfortunately Whitehouse had a disagreement with one of

the sons which resulted in him leaving the company.

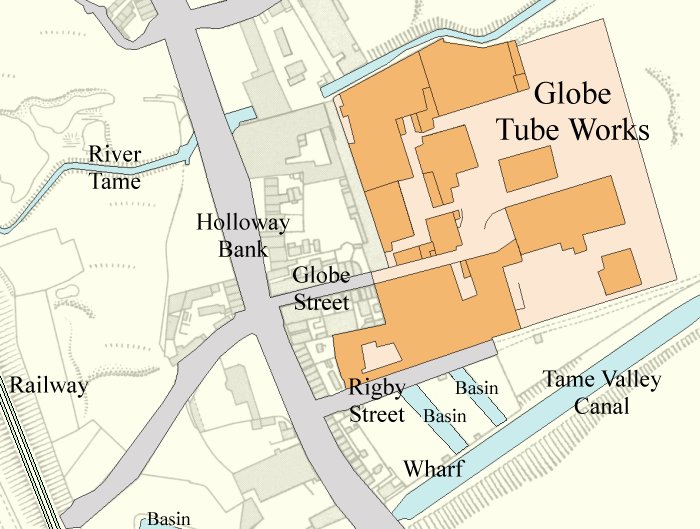

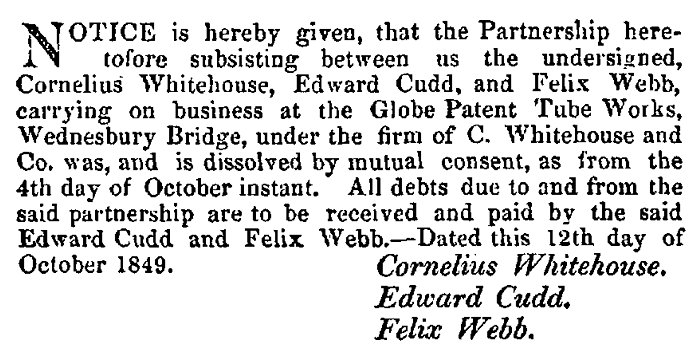

From then on he entered into a number of

unsuccessful business ventures. The first,

in partnership with a Mr. Chubb was a tube

making factory at Globe Works, Wednesbury

Bridge.

In Pigot & Company's 1842 National and

Commercial Directory, Cornelius Whitehouse

is listed under gun barrel manufacturers and

gun manufacturers in the Wednesbury section. |

In 1845 he took out another patent,

this time for the construction of welding and hammering

machines for the manufacture of tubes and gun barrels.

By 1849 he was also manufacturing lathe and press tools. Unfortunately the business at Globe Works was not

successful and resulted in Whitehouse loosing much of

his capital. He then moved to Wolverhampton and went into partnership with Edwin

Dixon, who had a tube factory at Monmore Green. Although

the partnership lasted for 20 years it was not

financially successful.

The location of Globe Tube Works.

From the London Gazette, 16th

October, 1849.

| Jones

Mercantile Directory

of the Iron

District, 1865:

Wednesbury

Whitehouse &

Company, gas tube

and gas fitting

manufacturers, Globe

Works. |

|

|

Cornelius continued to run Globe Tube Works until the

business closed in the depression that started in the

mid 1870s. The factory closed and was acquired by

John Spencer, who reopened it in

1882.

An advert from 1847.

Melville & Company's 1851 Wolverhampton Directory has

the following listing:

| Cornelius Whitehouse and Company,

manufacturers of patent iron tubes for

gas, water, and steam locomotive and

marine, of any diameter or thickness,

Monmore green. Whitehouse Cornelius,

patent gas tube manufacturer, Mount

Pleasant, house Monmore Green Cottage. |

|

An advert from 1861.

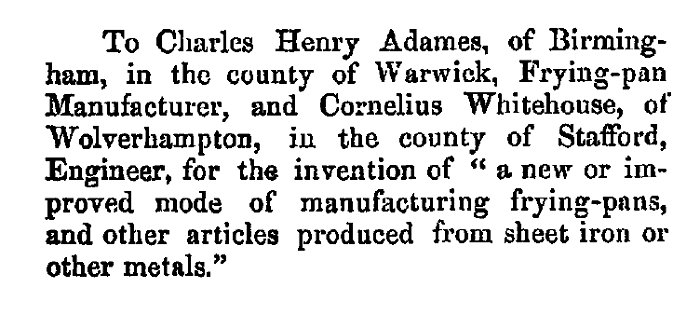

Whitehouse's final venture, in a holloware manufacturing

business at Birmingham ended prematurely in 1863 when a

workman was crushed by a falling piston.

From the London Gazette, 4th

January, 1861.

Cornelius married three times, first to Mary Peters in

June 1821, who sadly died in 1822. They had a son who

died at the age of three. Cornelius married again in

January 1826, to Lucy Aston the widow of Richmond Aston

of Bescot Hall. They had a son, Edward Searl Whitehouse,

born in 1826. He became a gunmaker. Cornelius's last

marriage in 1831 was to Charlotte Powers. Their son,

Denham Whitehouse, born around 1840, is listed in the

1881 census as a window pulley maker, employing 16 men,

14 boys, 3 girls, and living with his family at 15 Great

Brickkiln Street, Wolverhampton. Their other children

were Emma Whitehouse, Charlotte Whitehouse, and

Elizabeth Whitehouse.

Cornelius died on 7th August, 1883. At the time he was

living at his son's house in Great Brickkiln Street. Two of his nephews worked in tube

manufacturing. They both worked for him at Russells and

at Monmore Green, and one of them, John Brotherton,

founded Brotherton Tubes at the Imperial Tube Works in

Wolverhampton and later became the town's mayor. The

other, Thomas Pritchard, founded the South Staffordshire

Tube Works at Wednesbury.

His obituary in The Engineer:

|

The Engineer. 24th

August, 1883.

Cornelius Whitehouse

Those who remember

the great patent of Russell v. Ledsam,

which for many years dragged its slow

length through the various courts up to

the House of Lords, where it was finally

decided in the year 1848, will regret to

learn that Mr. Cornelius Whitehouse, one

of the inventors whose patent was in

dispute, died on the 7th

inst. in the eighty-ninth year of his

age. The invention was of the greatest

importance, and may be said to have laid

the foundation of the welded tube trade.

Whitehouse was originally a workman in

the employ of James Russell, tube

manufacturer, of Wednesbury. As far back

as the year 1825 he took out a patent

for making tubes, according to which the

skelp, previously bent up, was heated in

a furnace, and was welded by being

drawn, without a mandril, through a pair

of semicircular dies; or through

pincers, each jaw of which had a

semicircular groove or aperture. It

created quite a revolution in the trade,

the price of tubes being reduced to

one-half and for some sorts to two

thirds, and a much longer length could

be made.

The tubes were of

greater uniformity, both internally and

externally, and the trade came very soon

almost entirely into the hands of

Russell, to whom the patent had been

assigned, the inventor receiving an

annual sum of £300, together with a

house and certain other advantages.

Ledsam, the defendant in the action, was

the assignee of a patent taken out by

the late Richard Prosser, of Birmingham,

according to which tubes were welded by

drawing them through grooved rollers.

This was decided by

the court to be an infringement of

Whitehouse’s patent, the grooved rollers

being regarded as the mechanical

equivalent of Whitehouse's die, but the

litigation which was commenced in 1830

was not totally set at rest until 1848,

long after the patent and its extension

had expired. It was extended for six

years in 1839, on condition that an

annuity of £500 should be secured to the

inventor. The defendants contended that

the Crown had no power to insert such a

proviso, and they further alleged that

the application for extension had not

been made in time, and that the annuity

had not been duly paid.

Amongst the

testimony to the great value of the

invention given before the Privy Council

was that of Perkins, the patentee of a

well known system of warming buildings,

who stated that no other tubes would

have enabled him to carry out his

invention. They would bear bending cold,

and would stand a pressure of 5,000 lb.

on the inch. Francis Bramah, son of the

great inventor, also stated that the

introduction of the improved pipe

enabled him to dispense with the very

expensive copper tubing formerly used in

connection with hydraulic presses, which

cost 10s. per foot, whilst Russell's

pipe could be obtained of sufficient

strength at 1s. 3d. per foot.

Mr. Whitehouse

commenced business on his own account at

the Globe Tube Works, Wednesbury, in

1845, which, however, he relinquished to

Mr. John Spencer last year, as we

reported at the time. He also took out

several other patents in connection with

the manufacture of lap-welded tubes, but

none of such importance as his original

invention. No one will be surprised,

though it is much to be regretted, that

in common with many other patentees, the

benefits Mr. Whitehouse conferred upon

all countries through his invention did

not leave his latter days with such

substantial means as the importance of

the industry he created ought to have

afforded him. |

|

I would like to thank

|