|

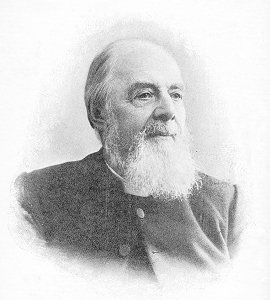

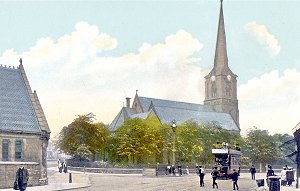

To see a World in a grain of sand, (William Blake, Auguries of Innocence) Life is rather like a tin of sardines - we're all of us looking for the key" (Alan Bennett, Beyond the Fringe) According to the Wolverhampton Red Book of 1914 St Marks "was consecrated on June 19th 1849. The first Vicar, the Rev. Alex. Baring-Gould, M.A., held the living for 23 years. He was succeeded by the Rev. George Everard, M.A., the Rev. C. L. Williams, and the Rev. H.L.R. Deck. The present vicar [the Rev. Robert G. Hunt, M.A.] was instituted in 1898". In an article on this website about the Rev. Baring Gould, the Revd. Dr. Glynne Watkin says that Baring Gould, one of a group of Evangelical Church of England men in Wolverhampton, declined better endowed livings, for fear that the Bishop would appoint an Anglo-Catholic to St. Mark's. When Baring Gold did eventually leave his replacement was George Everard, than whom nobody could have been more evangelical.

I think that the essential feature of Evangelicalism was the idea that the only hope for an individual who did not want to spend eternity enduring the torments of the damned was to come to God. This coming to God seems to have been a decision to commit yourself to God, that is, not just to go to church and try to be good, but to be conscious of God every waking moment of your life. It sometimes seems that the more sudden the conversion, the better. And that conversion had to be maintained throughout the rest of your life, as any backsliding might result, at least if you were unrepentant at the time of your death, in an eternal acquaintance with hell fire. The evangelicals seem to be fixated on the idea that "except that ye be born again, ye cannot enter the kingdom of God". You were saved from damnation by your having faith in God; but if you did good works all your life and were constantly engaged in helping your fellow men, but did not have faith, you would still be tipped into the pit. There were other Christians who liked the story of the kindly old farmer who never professed his faith, nor even attended church, but who was always helpful to all sorts and conditions on men. When asked if he did not fear God’s judgement, he said: "When you take your corn to the mill, does the miller ask by which route you brought it?". The Evangelicals may also be thought to have neglected somewhat the parable of the Good Samaritan or to have failed to give full weight to the assertion that, of faith, hope and charity, the greatest of these is charity. Certainly men like Everard performed their parish duties with enthusiasm, kept the church in good condition, raising funds for repair, rebuilding and so on, visiting the sick and the like. But, if they were asked what good works they did and ought to do, would certainly have answered that the greatest good they could do for others was to try to bring them to God, by preaching, missionary work, writing, or whatever. Compared with that, feeding the hungry or otherwise trying to relieve or improve man’s mortal lot, was very much secondary. And this prime task George Everard carried out in full measure. After Everard’s death the then Bishop of Durham said that the church could do with more men like him, whose whole life is manifestly suffused by the gospel of salvation. The Bishop thought that, in these days, people were pre-occupied "more with problems than with souls". That was certainly never Everard’s problem.

Everard was born in Spalding on the 4th June 1828, the seventh surviving child of his parents Richard and Anne Everard. Richard owned a linen factory in York. Why he lived in Spalding is not clear. When George was one year old his father died while on a business trip. Although the biography of George Everard makes no mention of financial matters, here and elsewhere, it seems that the family was left well enough off for them to be well provided for and George seems to have had funds available to him at least until he got a well remunerated incumbency. Up to the age of ten Everard’s life seems to have been a peculiar one. He was not allowed out of the house and its gardens. His only companions were his siblings. The youngest was Carrie, two years older than him, and the two of them received their schooling from the eldest sister, Annie, who was fourteen when she embarked on this educational task. But at the age of ten this isolation was relieved somewhat when he and his elder brother Harry were sent to a small grammar school attached to the church in Spalding. There the few pupils suffered neither discipline nor learning. But after they had been there a year Mrs. Everard decided, for reasons which are not explained, to move to Manchester. The other siblings having married or gone into business Harry went to school in York and George was sent to Manchester Grammar School, staring in Form 9 on the 11th February 1841. Here he is remembered as being very stout indeed, industrious, cheerful, obliging and forgiving. He had no interest in games, though throughout his life he was a firm believer in the daily constitutional. Then, in 1842, his mother died. That left George, at the age of fourteen, an orphan with "no one very well able to look after me". In fact it is not clear what he did for the next two years, but we then come across him getting a job as a clerk in the Manchester and Salford Bank and then, after a few months there, being offered a job as a clerk in Carlton’s warehouse. In 1846 came his call to God. St Paul had had his sudden conversion on the road to Damascus. Everard had his in the streets of Manchester. He was going home from the warehouse to his lodgings when a voice said to him: "You are growing more and more careless. Sermons do you no good. Soon you will be utterly hardened and then you will live and die in your sins. Better begin to pray! Better begin now!" So he did. He went back to his lodgings and prayed for God’s forgiveness. And he dedicated himself to the service of God.

Two points of interest might be mentioned here, in case they are significant. The most important one is that is seems beyond doubt that Everard was a manic-depressive. Periods of wild enthusiasm, accompanied by frenetic work in what he saw as the service of the Lord, and marked by great cheerfulness and bonhomie, were constantly interspersed with periods of deep depression, when he was scarcely able to do anything at all. It is Johnson’s black dog. Whether this was the result of his strange upbringing or of some physical cause, I cannot say. The other point is that although is parents were Baptists, Everard, when the call came, found his destiny in the Church of England. There is no explanation of why this was so. But Everard settled down to study every evening after work, engaging a private tutor to help him. Eventually he was admitted to St. John’s College, Cambridge, in 1847. There, for some odd reason, he read mathematics but engaged himself in every Christian activity that was going, assisting local clergy, taking Sunday School, joining the Cambridge University Prayer Union (for which he was proposed by a man who later became the vicar of Bilston), and so on. Notably he came into contact with a Trinity College student, J. W. Consterdine, with whom he took long constitutionals. It was Consterdine’s habit to take with him religious tracts and distribute them to anyone they came across. It seems to have been from this example that Everard picked up his life long obsession with tract distribution, which he saw as an effective way of bringing people onto the road to salvation; and of which he was to write many during his life and distribute tens of thousands. Everard was ordained in 1852 and his first appointment was as a curate in Ramsgate. In 1854 he moved to Marylebone where he stayed for three years. The most important event of this period must have been his meeting Miss Martha Maude, who he was to marry in 1859. Mary appears to have been the ideal vicar’s wife, supporting him and his parish work in every way and bringing up his family. She was to outlive him. In 1857 Everard took a curacy at Hastings but in that year he was offered the living of Framsden, a small village near Ispwich, and that he accepted as his first incumbency. Here Everard (and his wife) really got going on his Christian mission. And it was here that he started writing the tracts and books, which were to make him one of the most prolific Evangelical authors and one of the best known. In 1868 he was well enough known and highly enough regarded to be offered the living of St. Mark’s, Wolverhampton. This must have been a very sudden change from a small rural parish. But Everard felt that it was good for both the vicar and the parish if the incumbent moved on about every 10 years; and anyway he wanted a better education for his now growing brood than rural Suffolk could provide. So he asked God’s advice and, finding it to be in favour of the move, he moved.

In the biography of Everard there are two chapters on his life and work in Wolverhampton. The first such chapter was written by the Rev. Dr. T. Oliver, whose first curacy was with Everard at St. Mark’s, from 1869 to 1872. Oliver notes the warmth of the welcome he received from both the Everards and their kindness to him throughout his curacy. Oliver’s description of his first Sunday at St. Marks gives an interesting picture of the church at the time and of Everard’s frantic weekly schedule (Oliver writes of himself in the third person):

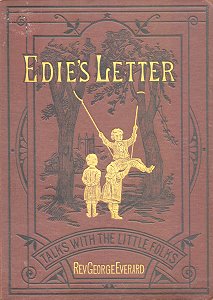

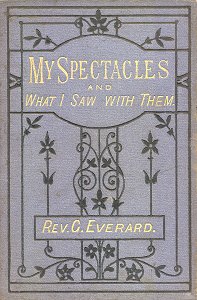

Everard would preach anywhere, in workshops and factories, in cottages and fields. And from time to time he would call in other evangelical preachers, one of the stars being Nevile Sherbrooke, once an officer of the 43rd Light Infantry but by then a vicar in the Church of England. He spent a week in Wolverhampton in April 1872, addressing congregations wherever they could be found, including "above one hundred men at a railway shed" and then "an audience of policemen in the new Town Hall". When the Royal Agricultural Show arrives in town in July 1871 a large tent was erected on the showground in West Park in which the Bishop of Lichfield, Dr. Selwyn preached once, and the Reverend Everard several times. Everard also distributed "many Testaments, tracts and little books". Sometimes Everard had to tackle more practical matters – but always, of course, with the furtherance of God’s kingdom firmly in mind. The passing of the Education Act of 1870 lead to the dread prospect of children being taught in schools professing no religion or, worse perhaps, a mistaken one. Oliver records: "the Vicar lost no time in enlisting the voluntary services of his willing people, who by their liberal contributions and by successfully holding a bazaar, enabled him to have the necessary work accomplished in dues time". The "necessary work" was the building of St.Mark’s schools, on land on the other side of St. Mark’s Road from the church. At some point, according to Jones, Everard was elected to the Wolverhampton School Board. Whilst at St. Mark’s Everard, who was obviously becoming very well known and well regarded in his own Church, was offered a colonial bishopric. Although this struck him as a wonderful opportunity to carry his evangelising work to new fields, he turned down the opportunity, feeling that "his sphere in the Master’s vineyard lay in the Home country". He had always had an interest in foreign missionary work and supported it with collections and donations whenever he could. But he was also a mission preacher, occasionally taking a week away from Wolverhampton to evangelise in other, usually industrial, parts of the country. Whilst at Wolverhampton Everard continued his writing of books and tracts unabated. I have not seen any of his tracts but I have noted around 40 books by him, ranging from slim volumes of not more than a couple of dozen pages to more substantial works. Their known dates - and not many of them are known - range from 1874 to 1898. In his biography it is said that he wrote his first tract in about 1863. In addition to this output Everard would have given at least one sermon a week. His literary output was prolific. Many of these books, to judge by their titles or, more often, their sub-titles, are about family life and worship or are written for children. He was certainly a family man and brought up a large family.

With the Angel of Death such a persistent visitor to St. Mark's vicarage, it may seem surprising that Everard was unshaken in his faith. He did not understand God's way in these matters but speculated that "The Good Shepherd loves the young and perhaps those loved dearest are soonest recalled", a comforting theory for bereaved parents from at least the time of the legend of Ganymede, but not necessarily one that would be comforting to the children not recalled. Yet at another point he says of the Prince of Wales and his attack of fever that "It was thought he could scarcely live another day. I believe it was only in answer to England's prayer that his life was spared". Why the nation's prayers for a Prince of no notably godly demeanour should have moved God more than those of a Wolverhampton vicar for his godly little daughter, he does not say or even speculate. And elsewhere: "God has a great love for the young and perhaps this is the reason that so many are taken away from the temptations and troubles of life before they reach full age". And while Everard submitted himself to God's will, up at Tettenhall Towers that old reprobate, Colonel Thorneycroft, was working hard to improve the town's sanitation. Perhaps it is not surprising that there is an emphasis on death in his "Talks with the Little Folks". He reminds his child audience that they must always be on good terms with God because you never know when you might die. This threat to keep children well behaved had been used since at least the time of Ecclesiastes, when the Preacher declaimed "Remember now thy Creator, in the days of thy youth"; to Edmund Gosse who remembered his father comforting him at night with the thought that if he died during the night the angels would care for him. Everard's teaching and preaching method was to take a few words, not from the Bible, but from everyday life, and to expound upon them in a Christian way, whatever their original context. This can perhaps best be described as an attention getting device. Thus, on hearing children in the vicarage garden playing on a swing, he hears them calling "My turn next!". He immediately thinks of several ways in which these words could be relevant to the religious life and he cannot help but remind the little ones that it might indeed be their turn next - their turn to die. Even inanimate objects could set him off. He records that on his way to a railway station he noticed "the bright and cheery light" of a line of thirty or forty street lamps - one of which "gave forth very little light. Either the burner was out of repair, or the pipe was stopped up or had a leakage; but anyway this particular lamp seemed to me quite a disgrace amongst its friends and neighbours". And then Everard immediately sets off on a sermon about those Christians whose light shines forth brightly and those who give forth but a dim flicker. Everard makes many reference to railway journeys and preaches from various aspects of them, which associates him, too closely for comfort, with the satirical sermon preached by Alan Bennet in Beyond the Fringe where the vicar walks out of the station without showing his ticket and hears the ticket collector shouting after him "Oi! Where do you think you are going?". Everard would have taken the development of this text very seriously.

But one of his starting points he expands on a little more and, it having been written in 1880, is of some interest today, showing what one Victorian thought of an amazing new invention - and on which we could perhaps pin an article on its analogies with the Internet. Everard had read a report in the Times on "this new and strange invention, the telephone". He is enthused. "We can hardly take it in. It was hard at first to believe the power of the telegraphic wire carrying a message as quick as thought to the other side of the globe. But here is something more marvellous still. The human voice can be heard and recognized miles distant; yes, hundreds, even thousands of miles will put no barrier in the way. One friend in a town in the north will be able to converse with a friend near Land's End. A husband in India will be able to have five minutes' talk with his wife he has left in England. The brother in France or Ireland will be able to make his voice heard by a brother or sister in London or Birmingham. ... It will help the merchant and manufacturer in giving orders to his work people in various places of work at a distance from his home or office. ... We heard of a concert in one city in America being distinctly heard in another some hundreds of miles off. And who can tell but some day a preacher may be heard at the same time by twenty congregations gathered together in as many churches. Perhaps the song of a favourite bird, the merry laugh of a little child, the very sigh or breathing of one we love may be heard thousands of miles away". And, having successfully predicted heavy breathing phone calls, Everard dashes on to discuss the most ancient and effective of telephones: prayer. Everard was certainly a member of the evangelical side of the Church of England. Both the style and content of his homilies make it plain. He refers on a number of occasions to his having conducted "missions" far from home. He is insistent that the word of the Lord can be preached at all times to all people, and he writes and distributes tracts. On one occasion he recalls being asked to "give a push" to a young man who was learning to ride a bicycle. He did so, surreptitiously slipping a tract into the young man's pockets as he did it - and also, of course, getting a text for a homily on giving people a push in the direction of the Christian life. Christianity, and the values it implies, were so much part of him that he tended to assume that its values were inherent in everyone and the working out of those values in practice was so obvious as hardly to need mention. Thus he exhorts the little folks to be good, not to do wrong and so on, without often descending to the particulars of what actions are right and what are wrong, and how you tell one from the other. Mostly his homilies are rants. But we get some idea of his attitudes and his audience on one of the few occasions when he gets down to the nitty gritty question of pocket money. "Perhaps children have their allowance - two pence or four pence or six pence or a shilling a week". He is clearly addressing middle class children, like his own and those of his own parish in one of the politer parts of Wolverhampton. The amounts of pocket money he mentions are sums which would have made quite a difference to many families in Wolverhampton. But the children reading Everard's books are the children of families which can afford books - the middle classes of the parish of St. Mark's and their like. Everard seems suddenly to realize this. "What a number of the poor might be made happy by a half or a quarter of what you spend on yourself". The residents of Carribee or Tin Shop Yard or crowded courts and alleys might well have agreed. Everard's answer is a typical one - there is no thought of changing the system, charity is the answer. He suggests that children should keep themselves safely in God's good books by giving to the missionary box to support "little heathen children" or at least by buying books for their own library. But the experience of a father breaks through: "I don't object to money being spent now and then in chocolate creams or some other pleasant dainties at the shop round the corner. All this is very well in its place". For this relief, much thanks. One does wonder, though, what Everard told his adult congregation about the eye of the needle. The Victorian enthusiasm for the archaeology and history of the Bible Lands had revealed the comforting discovery that the "Eye of the Needle" was the name of a gate in the walls of Jerusalem which a camel could get through, anyway with a certain amount of care. The instruction to sell all your goods, to give the proceeds to the poor and to "follow me" was, of course, susceptible to interpretation in its particular context.

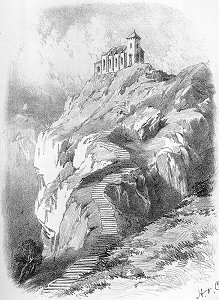

From references in his books and from his biography it is clear that the Reverend Everard had enjoyed a number of holidays on the Continent, especially in Switzerland. These seem often to have been working holidays, visiting local churches and preaching. Of course, Everard learnt moral lessons from the splendour of God's creation and, on a climbing expedition in Swizerland, he was able to reflect on the real significance of his mountaineering guide's instruction: "Hold fast to the rock!". Some things are clearly and specifically bad. The snares which Satan lays include gin palaces, public-houses and all forms of betting and gambling. In combination they were not just fatal to one's eternal soul but quick acting on the body too. He tells the cheerful story of two lads waiting to go in to Sunday School. But instead they go for a walk in the park. It is not clear that pubic parks are wicked in themselves but this one had a pub near its gate. The boys went in. They had a bet on who could drink a glass of spirits quicker. "But it was too much for the younger of the two. At three o'clock he was well and strong at the door of the Sunday School. At four o'clock he was lying dead on the sofa of a pubic house!" And again: "What perils arise through neglect of God's day, through bad company, novel reading, the ball room and the theatre, strong drink, light and foolish talk, idleness, self indulgence, passionate tempers and much more that I cannot name!". The novelist, Eileen Thorneycroft Fowler, lived only a few hundred yards from St. Mark's vicarage. But perhaps, if there are degrees of sin, she would not have been the worst sinner. Everard tells a story of a sixteen year old girl who "would not submit to those over her". She ran away and was married, then she went on the stage and "became an actress". Everard says no more. When the girl became an actress it was self evident that her degradation was complete. The Grand Theatre opened in 1894. In his Bibliography of Wolverhampton (1890) George T Lawley tried to list all the books published in Wolverhampton or written by Wolverhampton men. Such was Everard's output that Lawley is reduced to a summary. "He has written about 200 tracts and tiny books, mostly published by the Religious Tract Society. Only a few of his books may be mentioned here:

Some of his books have had a very large circulation, "Day by Day" of over 40,000 and "Not Your Own" about the same number". In 1884 Everard left Wolverhampton. He had stayed for 16 years, much longer than the ten years he felt was the most anyone should serve in one place. But he was offered the living of Dover and he accepted it, despite the fact, as his biography observed, that it meant leaving the mortal remains of his dear children behind in Wolverhampton. But Everard "would not allow any personal considerations to hinder his obedience to the Divine call". He took with him his curate, the Rev. T. W. Milligan, who later returned as the vicar of St Luke’s. In Dover Everard found a parish which was derelict, both in its church buildings and in its organisation. With his usual vigour he turned it round and it was in a healthy state when he left in 1893. His time there was marked by a lengthy trip to India, which was occasioned by his second daughter’s marrying the Rev. C. W. Thorne, who was a missionary with the Church Missionary Society. Everard accompanied his daughter to Poona (now Pune), attended the marriage there and then travelled extensively over the sub-continent, visiting CMS missions and, of course, preaching and distributing tracts as he went. It seems that by now Everard’s health was beginning to fail. It seems as if this illness was related to depression as the references to it in his biography suggest it was mainly manifested by general weakness and inertia. His doctor advised him to live further north, where the air would not be so "relaxing", and he accepted the living of St. Andrew’s, Southport. It did him no good and after a few months he had to resign. He stayed for some while with a friend in Kidderminster but then he, his wife and their two youngest daughter moved to Hampstead. This seems to have done the trick for he was soon out and about, at first in a Bath chair – from which he distributed tracts to passers-by on Hampstead Heath. In 1896 he seemed to be fully fit again and accepted the living of Teston, a small village near Maidenhead. His time here was much quieter than usual but still as committed to the cause: the hop pickers who came down from London for the season got used to his handing out tracts to them. But then his health deteriorated again. Despite visits to such place as Eastbourne, Lowestoft and Switzerland, he became weaker and weaker, with no enthusiasm or energy for any sort of activity. In 1899 he felt obliged to resign his living. He moved to Finchley, which put him nearer one of his daughters and grandchildren. It all did him good and he started writing and preaching again, travelling the country to do so. But in 1901 he went down again and early on Friday morning, 6th June, 1901 "the Lord gently put his servant to sleep". Says his biography: "It was in accordance with Mr. Everard’s own desire that he was laid to rest in the cemetery at Wolverhampton, in the same grave as his four children who had been taken ‘home’ whilst he was vicar of St. Mark’s". Everard was an evangelical Victorian vicar, with all the hopes and cares that went with it. He had the God of the Bible in his heart and on his shoulder. The Kingdom of God was more important and more real than this material world. On at least four occasions his God tested him further than he tested Abraham. Isaac lived; four of Everard's little ones did not. But he continued to rejoice in the mercy of the Lord. "Sweet are the uses of adversity, (Shakespeare, As You Like It) |