SAMUEL GRIFFITHS

|

|

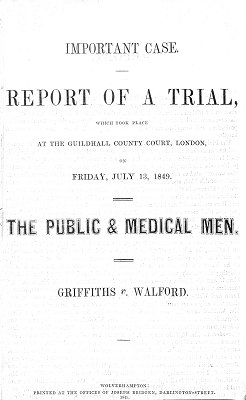

In 1849 a twelve page pamphlet was published in Wolverhampton. It's title page reads: Important Case. Report of a Trial, which took place at the Guildhall County Court, London, on Friday, July 13, 1849. The Public & Medical Men. Griffiths v Walford. Wolverhampton: printed at the offices of Joseph Bridgen, Darlington Street. 1849". The pamphlet consists of a report of this trial. It is clear that this is not a real case - or if it was, this report of it is a highly imaginative re-interpretation of what actually occurred. The star of the case is "The Plaintiff, Mr. Samuel Griffiths, oil and tallow merchant, of Wolverhampton and known as the sole proprietor of the celebrated 'Hot-Neck Grease', principally used in the manufacture of iron". And this pamphlet is in reality an advertising gimmick, certainly written by Samuel Griffiths himself. But it is not an advertisement for Hot-Neck Grease but for Sir James Murray's Fluid Magnesia. The story in the case - and this is much abbreviated |

from Griffiths' prolixity - is that on the lst April 1848 Griffiths was in London on business when "he felt himself taken ill with a violent irritability of the stomach". He therefore went in to "a chemists and druggists shop - that of the defendants, Messrs. Lunn and Walford, 149 Aldersgate-street" in order to get a dose of Murray's fluid magnesia. But Mr. Walford, assuring Griffiths that it would be all right because he, Walford, was a surgeon, gave him something to drink which turned out not to be Murray's fluid magnesia but Epsom Salts. Griffiths was immediately very ill. In this case he is therefore suing Walford for damages - which, if he got them, he would give to the South Staffordshire Hospital at Wolverhampton, because Griffiths was trying to establish the principle that druggists, chemists, surgeons or whoever should not be free to provide a substitute for what the customer has asked for.

The pamphlet gives much detail of the proceedings, cleverly incorporating much information about Murray's fluid magnesia and its benefits; and it reflects the uncertain and confused state of the much divided medical profession at that time. The last three paragraphs provide the outcome of the case and also show what this "report" was really about:

"The jury, after some discussion among themselves, retired to consider their verdict.

"In the meantime the judge intimated his wish to taste some of Sir James Murray's Fluid Magnesia, which, combined with the Acid Syrup, also of Sir James' preparation, appeared to make a cooling and refreshing effervescing beverage. Mr. Griffiths politely supplied his Honour with a glass of the mixture, which he pronounced, ex cathedra, to be "delicious". The opposing counsel and solicitor also requested a "refresher", and the whole court, as far as the bottle would go, proceeded to try Murray's Fluid Magnesia; after which they pronounced a unanimous verdict in its favour. Indeed, Mr. Mellor, the opposing counsel, went so far as to say that it was fortunate for his client that the jury had not accepted Mr. Griffiths's offer of tasting I prior to their retiring, as their verdict would, otherwise, have been most assuredly in his favour. At this moment the jury returned to their box, after an absence of half an hour, and returned a VERDICT FOR THE PLAINTIFF.

"The trail lasted five hours, and excited intense interest. Mr. Griffiths was highly complimented by all parties on the able manner in which he conducted his case, without professional assistance of any kind".