SAMUEL GRIFFITHS

2. Life in Wolverhampton 1849 - c.1866

Gale says that Samuel Griffiths' general interest in iron dates back

at least to 1849, for it was in that year that he started to publish

his Iron Trade Circular.

By 1850 he was doing well enough to build Whitmore Reans Hall.

Anthony Rose says: "Until 1850 there were less than 50 houses in the area,

but that year Councillor Samuel Griffiths, an ironmaster who had a somewhat

shady reputation, built Whitmore Reans Hall on the site of the principal

buildings belonging to Whitmore End House and Farm." He adds: "The building

had huge walls, which ran along Lower Street with a drive up to the house

via a gated entrance in Evans Street." Later the hall was owned by the

Evangelist Brothers and then became St. Winifred's Girls' Home. Rose

comments: "The grounds were often used by local schools for nature trails

and had a number of apple trees where much scrumping took place". Of the

Hall's later history, Rose tells us that two high-rise flats now "stand

roughly where Whitmore End House stood almost 160 years ago".

At some unknown date he became a town councillor in Wolverhampton. In

assessing him as a councillor, Jones, wrote:

Mr. Councillor Samuel Griffiths was a clever man. He had a wonderful

gift of language, his voice was either sympathetic or cheerful and loud.

Having great power of facial expression, he could be the jolliest friend

- lively and witty - or could appear the most simple, open-hearted

person imaginable. When wishing to gain his end he could plead with

pathos and eloquence; but he never lost sight of the "main chance."

Griffiths was concerned, as a councillor, in the great water scandal of

1854 and 1855. Jones, of course, objected to his conduct, which does

seem to have been a little heated, perhaps because the affair was bad for

his business; but it was Griffiths who proposed an honest solution which was

nearly that which eventually sorted out the matter.

|

Read about Griffiths' role

in the affair |

And he was still a councillor when he was involved in a

local bank's cessation of trading. According to Gale he went bankrupt in

1857, but recovered and carried on. Of this affair Jones writes:

FAILURE OF THE WOLVERHAMPTON BANK.

Wolverhampton, being in the centre of Staffordshire, was the capital

of the coal and iron trade. The town was surrounded by large numbers of

smelting furnaces and collieries. For some time past the iron and coal

trades were in a low and depressed condition. The miners of the district

were on strike against a proposed reduction of wages, many of the

smelting furnaces were closed down, and men were discharged every week

by hundreds. Owing to this state of things several of the largest and

most respected merchants and ironmasters in the town previously deemed

solvent suddenly failed to meet their engagements, having liabilities

which it was hopeless for them to attempt to discharge.

The principal bank, known as the Wolverhampton and Staffordshire

Bank, suddenly stopped payment. As the news spread crowds of people

rushed to the bank to read the notice on the closed doors. Despair

seemed impressed on every face, small groups of people stood about here

and there, talking to each other in whispers; fear and dismay haunted

those who felt they had lost their all. Among the largest debtors to the

bank was Councillor Samuel Griffiths. This was the man who made a

disturbance at the Council Meeting when the difficulty occurred in

reference to paying the cost of the defeated Waterworks Bill. Mr.

Griffiths sneeringly told the members to pay the debt themselves. The

same man now became an insolvent. Mr. Griffiths owed the bank £163,547,

and was the principal cause of the stoppage. The bank, after being

closed for three weeks, opened its doors again, much to the satisfaction

of the inhabitants. …

If his speculations did not turn out successfully, he was reckless

and daring. He is said to have completely hoodwinked the manager of the

bank.

During his insolvency he dressed in shabby, threadbare clothes, and

wore an old, battered hat. Meeting a friend in the street, who looked at

him with surprise, he laughed, and, with a wink in his eye, said: "Old

fellow, will this do for an insolvent ?"

Jones rather implies that Griffiths had managed to keep at least some of

his money. Certainly, he recovered from the disaster and by 1860 he

is listed in the official Mineral Statistics as operating blast furnaces at

Bilston and Wednesbury.

His ‘merchanting’ continued, though by 1861 he was described as a

‘metal broker’ (Harrison Harrod & Company’s Directory 1861).

At sometime about now the very large japanning company, Walton's, of

Old Hall, went into liquidation and all its property was auctioned off.

Griffiths saw this as a new business opportunity. Jones, in his

book, "The Story of Japan, Tin-Plate Working and Bicycle and Galvanising

Trades in Wolverhampton", gives this somewhat jaundiced account of this

episode in Samuel Griffith's entreprenurial life:

This gentleman was of a sanguine and enterprising temperament and

having made money by speculations in the iron trade, went to the sale

and bought a large number of the best patterns. Seeing an empty

factory, which stood near the Old Hall, he took it, intending to take

the customers of the old firm by offering Walton's patterns at reduced

prices. To make sure of the venture, he offered higher wages to

some of the workmen. But it was soon seen that Griffiths had made

a huge mistake; knowing nothing of the trade himself and meeting

fierce competition from other firms in the trade before him, he rapidly

lost his money, and after struggling for about ten months, being

disappointed at the result, he closed his works and went back to his

iron trade speculations.

In 1861 he stood for Parliament, unsuccessfully. An election

poster of the time, dated "Wolverhampton, 28th June, 1861" but signed

only "An Elector" weighs into Samuel. Amongst the welter

of abuse the writer suggests that almost anyone would be a better candidate

because "I reject the uncharitable surmise that there are others in the

Borough degraded to his level". Other parts of the tirade give us some

hints about Samuel's business and other activities.

... Mr. Griffiths has (he says) " for years been largely engaged in

the staple trade of the district." He has also been a chemist and a

dealer in grease and oil, and he has failed hitherto in every commercial

business which he has undertaken. Failed utterly! the dividends under

his triple insolvencies having been so mean as in many instances to

deter creditors from encountering the trifling cost and trouble of

proving their debts! He has therefore been "largely engaged" at the

expense of his creditors. His last failure was recent, and the wreck

total. After every failure he became more "largely engaged" than before;

but from the ruins of the last he has risen not merely self-renovated

like a phoenix, but with the potent power of renovating others, for he

has emerged not only to return to the "staple trade," and become a

purchaser

of costly works, but also to establish a Bank!

A later passage hurls more allegations at our hero:

... bear in mind the minor incidents in the career of

Mr. Griffiths. Recur to his action against a Fire Insurance Company, the

defence, the compromise! his prosecution and imprisonment for

infractions of the excise laws; recollect how "largely engaged" he was

in the bubble speculations of 1845; his quarrels and recriminations in

our Town Council; his prosecution for personating a voter at a

parliamentary election; his prosecution at Petty Sessions for an assault

!

|

Read the full text of the 1861

poster |

One would like to have more details of all

this. It is not even clear whether the prosecutions were successful.

One should bear in mind that political pamphleteering in the early

nineteenth century was not noted for its restrain but, even so, there must

be something behind all this.

Jones's account of this election also does not do Griffiths

many favours:

In 1861 he came forward as a candidate for Wolverhampton

in opposition to Villiers and Weguelin, Liberals, and A. Staveley Hill,

Conservative, and fought the election with great vigour. When the

candidates were nominated at the hustings erected in St. James's Square,

Samuel Griffiths had gathered his ironworkers together in hundreds, who

stood in front and shouted: "Griffiths for ever!" and, with their howls,

shouts, and groans, drowned the voices of the other candidates and their

friends. Mr. Griffiths made a long speech in favour of working-men,

promising them all sorts of privileges if they would vote for him. They

shouted: " We will! Griffiths for ever !" But when the poll was

declared, it was found that Griffiths was at the bottom! At that time

votes were only taken from £10 householders, and hardly any of his

workmen had votes.

Griffiths again became a bankrupt, and, although he

still did business as a metal broker, he seemed to gradually fall out of

sight, and went to live at Winchelsea, where he died suddenly. One

redeeming feature in his character was that, although he failed in

business several times, he always managed to pay the local tradesmen and

shopkeepers in full, and was open-handed and generous to the poor.

Jones obviously had difficulty in coming to terms with this

roistering and enthusiastic man with what were, to Jones, an odd mixture of

bonhomie, charitable intent and doubtful business practices. Maybe Jones's

report of Griffiths' sudden death was a kind of wishful thinking, for

Griffiths was far from dead but alive and well and living in London. Perhaps

the idea that he was dead reflects on his later complete disappearance from

Wolverhampton life. But that was not co come for a few years yet.

By 1862 Griffiths was in partnership as an ironmaker

with E. B. Thorneycroft and was probably involved financially in other

ironmaking concerns.

In 1865 he again intervened in a Parliamentary

election for Wolverhampton but does not seem to have stood. That

intervention is evidenced by a large poster he issued from Whitmore Reans

Hall on 5th July 1865. The poster covers a number of matters with

enthusiasm and a certain lack of order and direction. The burden of it is to

reassure voters that, contrary to reports, he has not said that he will not

stand at the election and may in fact do so. But in fact he did not and his

old opponent, Mr. Weguelin was again returned.

|

Read the

full text of the 1865 poster |

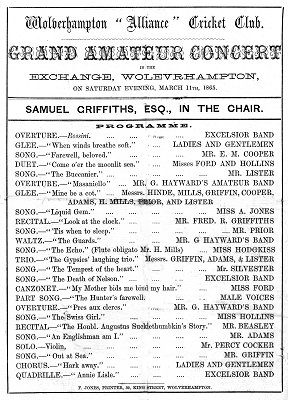

There is also evidence of another public

appearance by Samuel in the form of a surviving programme for the Grand

Amateur Concert of the Wolverhampton Alliance Cricket Club.

|

Presumably the Samuel Griffiths Esq. who was in the

chair was our Samuel Griffiths.

Whether he was really a cricketer or not, or whether this was

a publicity effort in advance of the election, we do not know.

But this sort of activity would have suited his rumbustuous

character. |

His own Iron Trade Circular shows Griffiths to be

still in the iron trade in 1865, but from then on his connection

with the manufacturing side of the iron trade seems to have declined,

for his name is missing from subsequent lists. The Griffiths family

history, as supplied by Joan Bird, re-inforces the idea that Griffiths

was not doing well at this time. Joan Bird writes:

Samuel's brother Thomas was a pork butcher and married

widow, Thirza Bradley in Birmingham in 1844. They had 11 children

between 1845 and 1865.

It seems that at some stage Thomas left the country for

an unknown

destination, possibly to avoid debt, at which time Thirza and the

children

were helped out financially by Thirza's family. It is not known where

they

lived at this time, but stories from the late Emma Jane Dunn, daughter

of Thirza Wills nee Griffiths, suggest that at some stage they spent

time in Essex.

By 1866 Thomas had returned, and the family seemed to have been living

at Whitmore Reans Hall prior to leaving England, as a death notice for

Thomas' son Samuel who died in Victoria, 1917 refers to "Thomas and

Thirza Griffiths, formerly of Whitmore Reans Hall, Wolverhampton".

Whether they lived with Samuel, or had bought the property from him, is

unknown At this time Thomas was in debt again, and part of a letter to

Thirza or Thomas from an unknown person, - possibly Samuel's wife,

mother, or a sibling, mentions that Samuel paid up these debts, and

found money for their fare to Australia, at great financial difficulty

to himself.

In August, 1866 Thomas, Thirza and family sailed on the "Champion of the

Seas" for Australia.

|

Proceed to the next page |

|