|

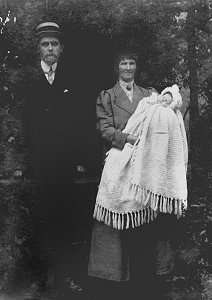

page 1 The Onions Family I was born the sixth child of a family of eleven in 1901 and I can recall a lot of things that happened, being the baby of the family for quite a while, as my parents lost the next three babies after me. My father, Joseph Onions, was born in 1865, the son of Edward Onions, a labourer. Joseph was a postman. He was a very upright and hard working man. My mother, Caroline, was born in 1867, the daughter of John Barker, Gentleman. She was a good religious woman. They were married at St. Mary’s Church, Wolverhampton on 15th June 1891 and lived initially in Thornley Street, Wolverhampton. The shop in All Saints Road By the time I was born, the family had moved to All Saints Road in Wolverhampton. We had a strict upbringing but ours was a very happy home. We never had much money, but we were all fed well and nicely dressed. Mother was a well-educated person, being taught at a School for Ladies in Clifton, Bristol. However, when her father married for the third time, his wife thought she should leave and earn her own living. So she was taken away from school and had to do just that.

I gathered that we were to open a shop in the front parlour. There was lots of activity as Father and my eldest brother, George, started to take all the furniture from the parlour and to put up shelves and to make a counter, and the little bow window had little fixtures fitted down the sides. Mother, who was very clever at making things, began sewing like mad – but, oh, what a surprise I got when I learnt it was to be a drapery shop. Childlike, I thought it would be a sweet shop! The great day arrived when the shop was to open. We were all very excited. Mother always said she opened that shop with just 30 shillings worth of goods. The fixtures were soon arrayed with babies’ clothes, dresses, petticoats, gowns etc. Mother seemed to have stocked the shop with everything. To keep her eye on things she had to have her sewing machine moved into the shop, as she was always sewing. Now we lived in the Black Country and it was all iron and steel works, so the people had to have hardwearing clothes. The womenfolk would like to have their husband’s shirts made of hardwearing material. They would buy the striped material from my mother; she would supply the shirt collar band for one penny three farthings; the buttons and rubberised collar (which only needed a wipe over with a soapy cloth, and it would be clean again) would cost threepence three farthings, and they would buy the lining, brown calico - and my mother would charge one shilling for making it up. They still carried on with their agency and it thrived better than ever. As the young people in the district got married, they would order all things like blankets and sheets, even furniture, too. Soon, they were getting along famously. Dad was doing quite a lot of business at the post office amongst his friends and soon we had to move to bigger premises, - and Father wanted a garden and to keep poultry. Soon we had a pony and trap, and we went out at weekends and holidays. It was great fun.

By this time Mother was selling anything and everything, from shoes to jewellery, but she discovered that she no longer had time to do the washing for us. I well remember the woman who came in the shop. She was a big, stout person and she said that she would do the washing and would come every Monday. I smile now when I think that that poor woman not only washed for eight of us but cleaned all the kitchen and back kitchen, the loo outside and swilled the yard, just for her dinner, one pint of beer, and one shilling. But I think Mother might have been good to her in other ways.

Mother then decided to add a deep lace frill on the bottom of the blind, and they looked very smart, such that everyone wanted them! This developed with the addition of 2 inches of lace being inserted above the frill. This made the blind trade boom. It got that people’s wealth was measured by how much lace they had got on their blinds! One day a horse and trap stopped outside our shop and a gentleman got out whom Mother recognised was the owner of a big store in Wolverhampton. He had come to ask her if she would stop selling the paper blinds as it was ruining his linen blind trade. Mother was very flattered, but she told him "Certainly not"! I would sit on the counter and Mother would sometimes let me count the money. There were other times when she would let me serve a customer or I would be allowed to put the reels of cotton away. She would always say I was a great help. I was about four years old when my mother had another baby, a boy. His name was Jackie. Ever faithful Auntie Agnes, who always used to come at these times to help, was tall and dark with blue eyes, and so kind. We all loved her very much. She was a dressmaker by trade, too, so she and Mom had a lot in common. She stayed with us until Mother was up and about again. But little Jackie was never strong and suffered convulsions and soon died.

I was still the baby of the family and would wait for my father to come home from work at dinnertime and stand on the shop step until Mother said "There he is"; and I would run as fast as I could and he would scoop me up into his arms and promptly drop me into his letter bag, with his arms around me, and carry me home. One day, Flossie’s headmistress came to see Mother and Father, to ask if they would let her go to the Papel Teacher’s Training Centre in Wolverhampton to train as a teacher, since she was very clever and the headmistress thought she should be given the chance. There was no such thing as school grants, everything had to be provided for by the parents but, after they thought it over, Dad decided that he would sell the pig so that Flossie could pay for her books and go and train to be a teacher. George, by this time, was getting a job in an office at the paint works in Wolverhampton. I had now started school and used to go with my other two sisters, Lizzie and Lena, but I remember how I always wanted to come home at playtime. I took a long time getting used to being away from Mother. I did miss her, so I’m afraid there were a lot of tears. All was going well, when tragedy struck our home again, for George came home ill with severe pains. The doctor was called in and said it was colic but George got worse, and was dead within three days. The shock numbed us all. Mother lost her voice and could not hear a thing. Father was almost demented with grief – he just kept on calling his name. Aunt Agnes came and took over and tried in vain to console my parents, but to no avail. I remember the funeral so well. Auntie had us girls dressed in white dresses with black sashes. There were crowds of people everywhere. George’s coffin lay on the counter he himself had made. It was open and I asked Father to lift me up to see him. He looked so nice and I said "He’s only asleep", whereupon Daddy dropped me so abruptly and fell across the coffin in uncontrollable tears. I have never seen such a big following as my brother had. There must have been hundreds as the street was full of mourners.. He was liked by everyone. Mother did not go to the funeral. As to why, I found out later. Another baby was born two weeks later. That poor mite cried from the time he was born until it died six weeks later. His name was Benjamin. Mother would have nothing more to do with the shop and the family doctor told my father that she would have to move out of the place or else she would go into a decline. All the shop goods were packed up and we moved a short distance away; but all Mother’s customers and friends used to come and call and it would open up all her grief again. Father decided that they needed to move further away and would try and find a house in the country. Weeks and weeks passed, but without any results. He came home one day, and asked Mother if she would like to live in Wolverhampton, in town, where she would have more opportunity to go out. Father had been told of a large flat which was available to let, and Mother agreed to go and have a look. |