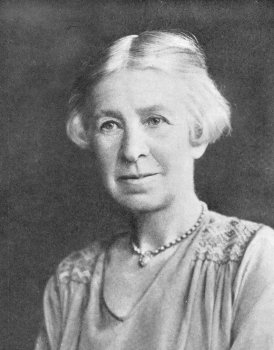

Evelyn Underhill was born in Wolverhampton on the 6th December, 1875. Her father was a barrister, Arthur Underhill. He was later to become a Bencher of Lincoln’s Inn and a Knight. His father was Henry Underhill, who had been the Town Clerk of Wolverhampton and a solicitor in the town. Her mother was Alice Lucy Ironmonger. Although she was born in her father’s house on the Penn Road the family lived mostly in London and she was educated at a private school in Folkestone and later at King’s College for Women, where she studied history and botany. Her father was a keen sailor and was a founder of, and for many years, the Commodore of, the Royal Cruising Club. Amongst their neighbours were another keen sailing family, the Stuart Moores and in 1907 Evelyn married one of the sons, a childhood friend, Hubert Stuart Moore, who was also a barrister. They lived at 50 Campden Hill Square. Underhill’s family was, formally, Church of England but they do not appear to have been committed Christians. Certainly she does not seem to have had God imposed on her in any sort of Evangelical way and as a young woman she seems to have been an atheist. She lead the comfortable life of the London middle classes, those with literary aspirations, but with an interest in sailing (at which she won prizes) and in law (her first book, “A Bar-Lamb’s Ballad Book”, being a selection of amusing poetry on legal themes). But she started to travel extensively in Europe, examining the art and architecture, which naturally included many churches and much religion painting. It was this experience, and particularly her seeing earlier Italian painting, which caused her to turn to God. This was a gradual acceptance of the notion of the divine and a supernatural world, not a sudden conversion and commitment to God. She developed her notions of the divine very much on her own, though, probably for memetic reasons, squarely within the Christian tradition. And, though she was strongly attracted to Roman Catholicism, she settled down, probably also for memetic reasons, in the Church of England and she can be seen as a leading member of the Anglo-Catholics, whose movement was so popular in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. Her extensive reading in Christian writings, particularly those of earlier, rather than contemporary, writers lead her in to mysticism (though late she preferred to use the term “spirituality” rather than “mysticism”). The Christian mystics try to reach a kind of knowledge of God and oneness with God during their lives. They sought to experience “Reality”, by which they meant the supernatural world rather than this world which has only the appearance of reality. But this experience is neotic – one that is so unlike this world that this world’s languages are inadequate to express it. For Underhill the important thing in life was to follow a path to this deeper spirituality. The path involved prayer and meditation but was not, for Underhill, something to be driven towards but something to be sought in a gradually developing spirituality. Following the path was difficult and one would be, as Underhill herself was, beset by doubts, even over long periods of time. You would probably need help along the path. This would come from others who had made or were making the spiritual journey (and who might or might not be ordained members of a church). In Underhill’s case she was guided by Baron Friedrich von Hugel (and some people see her as a disciple of his rather than as an original force). Should one achieve an advanced state of spirituality then God will work through you to affect other people’s lives and, although love of God was your first concern, you would have and exhibit a love for all humanity. In many ways this mysticism has similarities to other religions, and perhaps Bhuddism is the most obvious parallel – the Bhudda underwent a prolonged period of meditation to reach a oneness with the eternal. He delayed his departure to Nirvana in order to teach and bring others along the path. Christian mystics did not have that option. But unlike Bhuddists, whose holy men retreat from this world, or enclosed Christian orders, who do likewise. (Underhill does not seem to have thought that God needs to be asked to get him to intercede in human affairs – his intercession comes through spiritual people and the spiritual life). In Christian mysticism there is also a marked reliance on meditation, a reliance on a guru and a personal, rather than an institutional, approach to God. Underhill thought that everyone could take this path and get on with their lives in this world too – a practical spirituality – and that participation in political debates by spiritual people was inevitable. Underhill’s religious position was not based on current Church of England thought but came from her own attempts to understand God, the transcendant. She operated within the Church of England and, indeed, thought that communal worship was an important part of the path to deeper spirituality; but her own stance was personal and ecumenical. In World War I Underhill worked at the Admiralty. By World War II she had become a pacifist. She recognised that Hitler and the National Socialists were evil (and the Nazis were nothing if not Nordic mystics) but argued that they could not be overcome by war because all war was evil; only love could overcome evil. How that would have worked out in practice is not clear. Underhill wrote a very great deal, lectured, gave talks on radio, lead retreats and, largely through a very extensive correspondence, acted as a guide to many who were trying to take the same path to spirituality. The most notable feature of her guidance was her insistence on trying the remain relaxed about making progress along the path – too great a striving would lead to nowhere except despair. But as her spirituality was practical she continued to live much of the social life which would have been expected of a leading barrister’s wife (though they failed to produce any children) and she did social work in the slums of London. She produced at least 350 publications, including both books and articles and retreat notes and she was, for many years, the theological correspondent of “The Spectator” and, afterwards, of “Time and Tide”. She died on the 15th June 1941 and is buried in the churchyard of St. John’s Church, Hampstead. |