|

By 1841 Wallis had moved to London where he joined the Normal Class for the Future Masters at the Central School of Design at Somerset House. It is clear that, to have qualified for this teacher training course, he must already have been able to show an impressive body of work. This school was then under the direction of William Dyce. In our context there are two important things about Dyce. In the first place he has been described as “one of the first teachers to place ... faith in botanical nature as a source of inspiration” and his later published work shows his commitment to this subject as well as the important part it played in the teaching of the Central School. This must have appealed to Wallis and relates back to his paper “On the Principles of Natural Form”. In the second place Dyce had been asked by the council of the Central School to report on the organisation and teaching methods of schools of design in France and Germany. He visited both of these countries and reported in 1838; and it was on the basis of that report that the Central School's curriculum and teaching were redesigned. When Wallis was there he was experiencing at first hand the latest, leading views on industrial art education. Wallis was a great success at the school as, according to his son, he was awarded six exhibitions (in the sense of prizes or scholarships) by the Board of Trade.

By January 1843 Wallis had left the Central School and had been appointed the Headmaster of the Spitalfields School of Design. (Spitalfields was a great centre of silk weaving). He was only there until the December. What went wrong can be deduced from a letter Wallis wrote in 1860 in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School: “I was Head Master of the Spitalfields School of Design seventeen years ago, and saw plainly enough that the manufacturers there, with their school &c, were, to use an old illustration, like “a cow in a farthingale”, which, for the benefit of modern Wolverhampton folk, may be translated into “a collier in a crinoline”. How to use it, what to do with it, supported as it was almost entirely by the Government and a west-end charity box, they did not know. It could not make them what they wanted, cheap designs in the French fashion, because its object was to correct as well as cultivate taste. Growth and progressive development they did not believe in, because it was beyond their comprehension. It was not my duty to point out how the school could be made useful, but I did so nevertheless, and of course gave offence accordingly.” It might be noted here that Wallis seems always to have been an aggressive debater, not much given to mincing his words or suffering gladly those he thought fools. He probably lacked an easy charm and tact in life as in his writing. Having had two years at grammar school, left at 16, and never been to university to study the classics, he never espoused the polysyllabic style of rolling periods, that so many Victorians aspired to. In December of that year, 1843, he was appointed to the Manchester School of Design which had decided to rearrange its teaching on the principles adopted by the Central School. Whitworth Wallis says that his father was "promoted" to Manchester from Spitalfields. It may well be that, as Wallis never suffered fools (or some quite sensible people) gladly, it was seen as a good idea to transfer him elsewhere.

He seems to have been successful in his work at Manchester but he left it in telling circumstances. It seems, though the Biograph is not completely clear on the matter, that Dyce having left the Central School, the government decided that schools of design should adopt a different course of instruction, which included the drawing of the human figure “from flat examples”, was to be adopted. Wallis, who had taught from casts and anatomy, objected to this and probably to other features of the course as well, for he had, by this time, got his own decided opinions on how a course of industrial art should be organised and claimed to have proved its value at Manchester. Wallis resigned. In "Rides on Railways" (London, 1851) Samuel Sidney writes at some length on these matters:

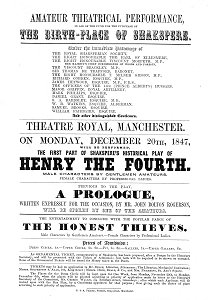

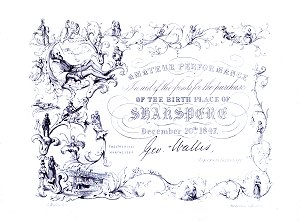

In 1844, whilst still at the Manchester School, he had visited Paris for the Quinquennial Exhibition of the National Art and Industry of France and inspected the Ecole de Dessin. Whitworth Wallis refers to his father as having been sent to Paris, presumably by the Central School or the Board of Trade. From these experiences Wallis deduced, according to the Biograph, that periodical displays of industrial art were essential but that the French system of design education was not applicable to England. He deals with what he perceives as the deficiencies of the French system of art education in his "Letter to the Council" and points out that the fact that the people produced by this system might be good does not prove that the same system would produce good results here because the whole context of art education was different. It is not clear when Wallis left Manchester. The Biograph refers to his being there “from two to three years” which may mean that he left at the end of 1844 or sometime in 1845; but the RSA obituary says that he held this office until 1846. And his "Letter to the Council" is dated 30th October 1845 when he was still in office. The performance put on for the Shakespeare Birth Place fund (mentioned in the captions to the images above) was on 20th December 1847 and refers to Wallis's address as 53 Renshaw Street, Greenhayes and there other indications in that material that he was in Manchester at that date. But it could well be that he was continuing in a role he had started well before he left Manchester. On the whole it seems likely that he left Manchester at the end of 1845 or at the beginning of 1846. An idea of what Wallis was doing between 1845 and 1851 is given by Widar Halen who, in his book on Christopher Dresser, writes: “Two other famous protagonists in the early history of the reform of design in Victorian Britain were George Wallis and Owen Jones, both of whom lectured at the School in the late 1840s and exercised a considerable influence on Dresser’s early education”. Dresser himself mentioned that he attended Wallis’s lectures “when quite a boy” – he went there in 1847 at the age of 13. So presumably at this time Wallis was a teacher at the Government School of Design at Somerset House (which moved to Marlborough House in 1852) and it may be that it was to take up this appointment that he left Manchester. Presumably, also, he stopped that work when he took up his next appointment in Birmingham. He had also started a long connection with the Art Journal. Whitworth Wallis says that his father's report on the Paris Exhibition of 1844 lead (though he does not say how) to the Manchester Exhibition of 1846. This drew Wallis to the attention of Sir Henry Cole who asked him to write for the Art Journal. In 1845-46, perhaps on leaving Manchester, he organised an Exhibition of Art and Industry at the Royal Institution. (The Art Union, later the Art Journal, had a special supplement on the exhibition in its January 1846 issue). During the course of this Exhibition he lectured on “The History, Principles and Practice of Ornamental and Decorative Art”. “This”, says the Biograph, “was really the first effort to systematically illustrate the relation of art to industry”. In the Spring of 1847 Wallis was, according to his son, requested by the Board of Trade to report on the condition of Schools of Design in the country and to "prepare a systematic statement of his views regarding a progressive system of instruction". Wallis's report, dated 19th June 1847, was entitled "A Draft of a Plan of Instruction in Art and Science, furnished by Mr. George Wallis to Mr. Shaw Lefevre, Secretary to the Board of Trade". Of this report Wallis's son says: "It lays out a systematic plan of instruction for Schools of Design and to this day forms the basis for the instruction in Government Schools all over the country." This is a large claim, made by a proud son. It deserves further investigation. To this Whitworth Wallis adds: "Especially important was his systematic attempt to introduce the teaching of elementary drawing from the blackboard, which he had used in experimental classes in 1838 in this town [sc. Wolverhampton]. It is therefore probable that Mr. Wallis' efforts in Wolverhampton were the earliest in this country in teaching elementary art by means of the blackboard.". It would be interesting to check this against the general history of the backboard in teaching. In 1848 Sir Henry Cole established the Journal of Design, to which Wallis contributed a number of articles, the first of which was “Provincial Exhibitions of Manufactured Art”. Wallis seems to have been closely associated with Cole at this time. David Crowley says: “Through the Schools of Design and Summerley’s Art Manufacture there emerged a core of artists, designers and intellectuals linked to Cole. The keys figures in this - ‘the Cole Group’ – were [John Bell, Richard Redgrave, William Dyce, Daniel Maclise and] Matthew Digby Wyatt, Ralph Nicholson Wornum, Gottfried Semper, Owen Jones and George Wallis. .... The Cole Group became the design establishment of mid-19th century Britain”. |