A history of Wolverhampton written in 1985 to celebrate the town's millennium by the late Keith FarleyWolverhampton 985 - 1985with special reference to Frank Mason and Geoff Pennock Foundation The year 985AD, saw the foundation of Wolverhampton. It was in that year that the Anglo Saxon King Aethelred made a grant of land at Heantune (Wolverhampton) to the town's benefactoress Lady Wulfruna. It is generally thought that the Lady Wulfruna was the sister of the old King, Edgar, who had died in 976. The king's grant covered an area of land bounded by Bilsatena (Bilston), Seeges League (Sedgley) and Tresel (Trysull). Nine years after the original grant the Lady Wulfruna endowed a minster church which stood on the present site of St. Peter's Church. While the original Charter gave Lady Wulfruna the absolute right to nominate an heir to her lands, it was only eightyone years after the charter that the complete map of England and Wales had to be redrawn following the Norman conquest. The new king rewarded his faithful followers with grants of land, and one of his retainers, Samson of Bayeaux received Heantun or Hantone as the Domesday Book records the name in 1086. According to the entry in the Domesday Book the Canons of Hantone held the land from Samson and at Hantone were to be found fourteen slaves, six villagers and thirty smallholders with a total of nineteen ploughs. Most of the people mentioned in the return would have had families and there would have been the canons and other church people, making a probable total of over two hundred people - a fair sized community for the time. During the next two hundred years the ownership of the lands of Hantone underwent numerous changes including the Prior and monks of St. Mary's Worcester, Roger, the Bishop of Salisbury, the Bishop of Chester and once again St. Mary's at Worcester. It was during the reign of King Stephen (1135-1154) that there is reference to the church of Wulfrunhampton. The dedication of the church remained to St. Mary's, although there was a brief change to St Peter and Paul during the early part of the the thirteenth century - it was during the fifteenth century that the dedication was permanently altered to St. Peter. Early development While Wolverhampton was still a relatively small settlement surrounded by dense forests, it was also developing as a centre for trade. The earliest known date of the existence of some form of market in Wolverhampton is 1179 and there is another reference in 1204 when King John took great exception to the existence of a market without a royal charter. It was on the fourth day of February 1258 that King Henry III granted a charter for a market and fair to the Lord of the Manor, Giles de Erdington, the Dean of Wolverhampton. The charter conferred the right of a weekly market to be held on Wednesdays and a fair to be held every year commencing on the vigil of the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul and to last eight days. It was five years later that the same Dean of Wolverhampton created a borough out of his manor (not including the other manor in Wolverhampton at that time, namely Stowheath Manor). It is interesting to note that after the series of demographic crises that struck England during the following three hundred years the market of Wolverhampton was still in existence while most of the neighbouring communities had ceased to hold weekly markets. The Wool Trade in WolverhamptonThe reason may have been the continuing importance of the wool trade. While there is little corroborative evidence it has been traditionally held that Wolverhampton was one of the 'staple' towns involved in the wool trade of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Indeed, in 1859 the coats of arms of the City of London, the Drapers' Company and the Merchants of the Staple were found on a building in Lichfield Street during its demolition. It is also no accident that a journey around the town centre takes a visitor past Blossoms Fold, Townwell Fold and Farmers Fold. Also in the national archives there are numerous references to local families being involved in the wool trade, notably the Levesons, the Ridleys and the Cresswells. The Levesons prospered from the wool trade to such a degree that by the fifteenth century they were the wealthiest family in the area. Virtually every change in land ownership around the town involved them in some way or other. By the end of the century the manor of Stowheath, which included parts of Bilston, Willenhall and Wolverhampton, was almost totally in their hands.

It was also wealth from the woollen cloth trade that resulted in the foundation of the town's grammar school. Sir Stephen Jenyns had moved away from Wolverhampton and settled in London where he had become a member of the Merchant Tailor's Guild, and at one time the Lord Mayor of London. However he did not forget his birthplace and in 1512 he founded the grammar school, providing the funds for its building and a further sum of money, the yearly interest on which would pay for the continued running of the school. The school was built near the edge of the town in John's Lane (now St. Johns Street). The building was demolished and replaced by a new one in 1714 which was itself also demolished at the time of the building of the Mander Centre. By this time the Grammar School had already been rebuilt on its present site on Compton Road. Very little evidence remains of the Wolverhampton of the Tudor period although two buildings, 19 Victoria Street (Lindy-Lou's) and 44 Exchange Street, are still standing. The former is probably a result of the rebuilding which occurred after the first great fire in Wolverhampton in April 1590. The Great Fire of 1590

The total cost of the damage was assessed at over £8500, a vast amount for the end of the seventeenth century. In September 1703 the inhabitants of Wolverhampton purchased a fire engine and twenty-four buckets for the water. The engine involved a simple box pump with a leather hose mounted on two wheels from which water was pumped out by a force of six men, three on each side.

Wolverhampton and the Gunpowder Plot

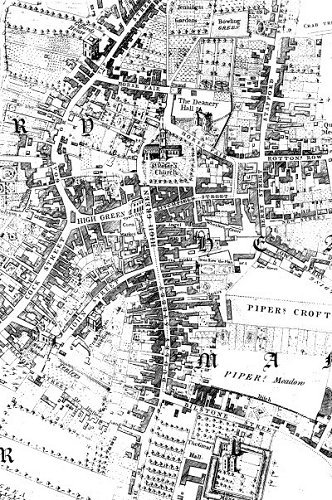

Two other men named Thomas Smart and John Holyhead of Rowely Regis were subsequently charged with sheltering the renegades. They were tried in Wolverhampton by a judge, specially bought from Ludlow, and executed in High Green (Queen Square) on or about January 27 1606. Taylor's Map of 1750

In Tup Street you would see two outstanding large houses built in the Georgian style. The first of these houses was built by John Molineux and his son, Benjamin, between 1740 and 1750. The second house, a little nearer to the town centre, was built a little earlier by Peter Giffard. The work began in either 1727 or 1728. Molineux House

In 1889 the Molineux Hotel (as it had become known) became the headquarters of the Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club after they had left their original Dudley Road premises. Giffard House

It is believed that a Warwick architect named Francis Smith designed the building (the same architect designed Chillington Hall) and William Hollis was the builder. Hollis was paid £3-10s-0d for knocking down the old building and the new house cost £1069-2s-2½d. Many of the bricks were made on the site from clay dug out when the cellars were excavated, most of this work being done by Thomas Birch who received £57-8s-5½d for the job. The wood for the house came from Norway. St. Peter and St. Paul's Church adjoins Giffard House and was built as a replacement for the existing chapel situated inside the house itself. The church was built at the direction of Bishop John Milner who lived at Giffard House from 1804 until his death in 1826. While the Bishop set aside £1000 for the church's building, he died before it was completed. High Green and the Town Centre

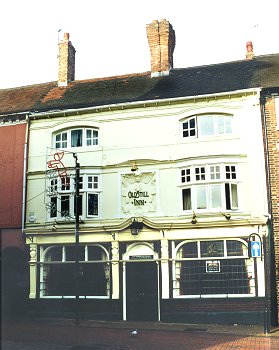

The most usual means of keeping discipline was by way of a birch rod and a record dated 1757 shows that boys who were late for school would receive six strokes of the birch, and girls would be whipped! Eight senior boys were appointed to report those who "cursed, swore, told lies or spoke unmannerly". One of the early subscribers to the Charity School was Button Gwinnett, a merchant from Bristol who married a local girl named Anne Bowne in April 1757. The importance of Gwinnett however lies in the fact that after business failures in England he went to North America and in 1776 was one of the fifty-six signatories of the American Declaration of Independence. Two other important buildings stood at the east end of High Green. They were the two greatest of Wolverhampton's coaching inns, the 'Angel' and the 'Swan'. The Angel stood where Lloyds Bank now stands and the Swan was a little further in the present day Dudley Street. These were not ale houses or public houses, they were the eighteenth century counterparts of modern hotels. Quite close to the sites of the coaching inns was to be one of Wolverhampton's earliest examples of town planning. Between 1751 and 1753 much of King Street was built including the present day Old Still Inn which was known originally as 14 King Street.

Shortly after the publication of Taylor's map a new church was opened for worship. The church was built, standing on its own in the open spaces which lay between present day Worcester Street and Snowhill. The church was St. Johns built of brick "cased" in Perton sandstone.

During a journey for repair the organ was "stranded" in Wolverhampton when the owner died in the town. The church purchased the organ from the owner's widow for £500. Finally, the only other church official mentioned in these early years is William Shaw, the dog whipper. He was paid six shillings a year to "expel from the church such dogs as do not behave well". The job was usually performed by gripping the dog around the neck with a pair of wooden tongs kept in the church for the purpose. In l778 the church records show the payment of one shilling for "a pair of second-hand breeches for old Shaw". Apparently Mr. Shaw had been "whipping" for at least twenty years. There are buildings within the modern boundaries of Wolverhampton which would not have appeared on Taylor's map but which existed before 1750. Outside the town centre Such buildings include Graiseley Old Hall which is situated behind the Royal Wolverhampton School and is believed to date back to about 1485. It was originally, the property of Nicholas Ridley, a merchant of the Staple, who was involved in exporting raw and processed wool through Calais to the continent. By 1665 the house was occupied by a John Whitehead who had to pay Hearth Tax for the property. The site was purchased by the Royal School in 1930. Gorsty Hayes Cottage in Tettenhall was originally built as a foresters lodge, when Tettenhall was on the boundary of the three Royal forests of Cannock, Brewood and Kinver. It is possible that the building was completed in the sixteenth century. Bilston's Greyhound and Punchbowl Inn dates from about 1450 and was originally built as a manor house by John de Mollesley when he married the daughter of Edwin de Bilston and called Stowheath Manor. It was at the Manor house that the Royal Commissioners stayed in 1508 when they visited the area to enquire into the state of St. Leonard's Church. The Nineteenth Century

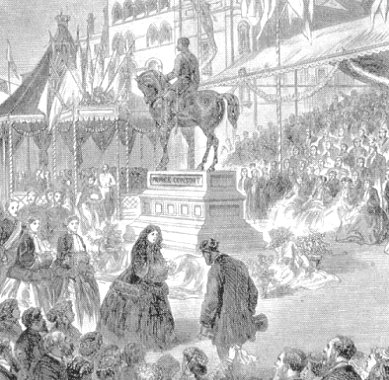

The Commissioners were named and were all local people with property worth more than £12 per year and owning land or goods worth more than £1000. Regular meetings were organised for the Commissioners at the Red Lion inn (later to be purchased and demolished to provide the site for the Town Hall next to the Civic Hall). Each Commissioner was expected to pay sixpence "to be spent in drink for the good of the house." Despite the "conviviality" of the meetings, the Commissioners did a lot of useful work, including the prohibition of animal slaughtering in the streets, the provision of scavengers to go round the town once a week and "by bell, loud voice or otherwise" inform the inhabitants in courts, passages or places into which carts cannot pass, to bring forth their ashes etc." By the end of the century the Commissioners had something to show for the work, street lighting had been provided in the form of an oil lamp at every street corner and over the doorway of every inn, householders had to clean the street in front of their houses every Thursday and Saturday (helped by paupers from the poor house) and the streets had been named and John Smith had been paid 2/6d per street for painting the names in white lettering on black boards six inches high. Water supply had been improved by the sinking of ten new wells and the provision of a great water tank in the market place. Policing had been improved with the appointment of ten watchmen at 8/- per week each, although the watchmen were probably, quite elderly gentlemen. There is a story about one gang of youths who tied a watchman's box to the London coach just as it left the Angel. Despite the 'success' of the Commissioners, more of the people of Wolverhampton were demanding the right to choose who should run the town. The 1832 Reform Act resulted in Wolverhampton sending two members of Parliament to Westminster for the first time. Encouraged by this, many of the town's leading citizens began to demand borough status for the town. After a town meeting a "Petition of the householders of the township of Wolverhampton" was duly presented "To the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty". On March 15th 1848 Wolverhampton was granted a Charter and officially became a borough governed by a council consisting of a mayor, 36 councillors and 12 aldermen. The first municipal election was held on May 12th 1848, and an ironmaster, Mr. G.B. Thorneycroft became the first Mayor. It was Mr. Thorneycroft who purchased the mace from St. Mawes in Cornwall which became, and still is, the Wolverhampton mace. It was during the year of the Reform Act that Wolverhampton was affected by its first serious epidemic of cholera with the first case reported on August 8th, four days after the first case reported in Bilston. Wolverhampton's epidemic was to be far less severe than the Bilston epidemic. There had been reports of cholera on the continent during 1831 and as a result Boards of Health were established. The Wolverhampton Board was under the chairmanship of Reverend Clare of St. George's Church. Also as a further prevention streets were cleared up and lime was made freely available from a coach house owned by Mr. Hills in Pigstye Walk. Unfortunately the measures did not prevent the outbreak. The first case reported was a man who lived in Brickkiln Street and the whole number of reported cases was 578 with 193 deaths. There were 220 male cases, 219 female cases and 139 children under the age of twelve. The deaths were 73, 72 and 38 respectively. Many of the dead were buried in St. George's churchyard. This compares "favourably" with the figures for Bilston where there were 3568 cases with 742 deaths. The distribution of cholera cases in Wolverhampton varied with the more squalid living areas being particularly affected. One example was the Carribee Island district off Stafford Street, a small alleyway, with a stagnant ditch running along it filled with resident's sewage. The lane was inhabited by mainly Irish immigrants and the deaths and cases reported were high. Foundry workers were a group who also suffered heavily from cholera despite their better wages and reasonable living conditions. They worked in extremely, high temperatures and close atmospheres for up to twelve hours and so these men were at risk. In 1849 there was another cholera epidemic, as a result of which the new Council decided to buy up the Waterworks Company and take charge of the town's water supply. However the Company refused to hand over its lucrative business and a legal wrangle ensued. The Town Council lost and faced a bill for £6,500. The amount had to be found by the members of the Council but not one of the members was willing to pay. And so, bailiffs were instructed to seize the property of the town. At one time or another the bailiffs seized the Town Hall furniture, the Mayor's robes and the mace, even the Town Clerk's pen. They seized the police barracks, including the policemen's helmets, uniforms and handcuffs. It was said "the policemen were unable to get up for lack of uniforms, or to stay in bed for lack of beds." The town's fire engine was seized and the whole thing became rather a joke. It was in 1855 that Councillor Edward Perry took on the duties of Mayor and determined to put an end to the activities of the bailiffs. He succeeded by way of a voluntary rate of one shilling in the pound. By 1868 the town had taken over the water undertaking without any difficulty. Queen Victoria's Visit The town was honoured by the presence of Queen Victoria on only one occasion, in November 1866. However her presence was particularly important since it marked possibly her first public appearance after the death of Prince Albert. Wolverhampton, like many other towns, erected a statue in honour of the dead Prince Consort and invited the Queen to unveil the sculpture. Thomas Thorneycroft the sculptor completed the statue on October 1, 1866 at a cost of £l,150 and then it was sent away to be cast in bronze. The statue was put in position on High Green (Queen Square) at the beginning of November. On November 21, 1866 the Queen accepted the invitation which left just eight days for the visit to be organised. Houses along the route to be followed were painted and cleaned up. Flags, banners and wreaths were positioned, chinese lanterns were hung, clock faces were decorated and one electric light even appeared outside one shop.

Communications The successful development of industry depended on many factors one of which was an efficient communication system, and Wolverhampton was at the centre of many of the developments in communication. The main roads into the town in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were turnpike roads administered by Turnpike Trusts who were allowed to levy a toll which was collected at the Tollgate or Turnpike. Some of the Tollgates into Wolverhampton were the Tettenhall Gate (Chapel Ash), Bilston Street Gate, Willenhall Gate and Compton Gate. In 1824 the gates at Tettenhall and Bilston Street showed profits of over £1200 each. The improvement in roads resulted in an increase in the number of stagecoaches and mail coaches. Wolverhampton was served by many famous coaches including Red Rover, Shropshire Hero, Beehive, Royal Dart and Wonder. The Wonder ran daily, from Shrewsbury to London via Wolverhampton, Coventry and St. Albans. It came up the Tettenhall Road, into Salop Street, round the corner into Cock Street and under the archway entrance into the yard of the New Hotel. Within sixty seconds the passengers would climb aboard, parcels packed, the horses changed and the coach would be out of the yard once again. One Monday in 1838 the Wonder left its London terminus at the same time that a new steam train left Euston. The Wonder beat the train to Birmingham by twenty minutes. The regular timetable of the Wonder involved its departure from the Bull and Mouth Inn in London at 6.30am, arrival at Coventry at 4.02pm and Wolverhampton at 7.36pm. The fare from Wolverhampton to London was 34/- inside and 17/- outside. In 1827 coaches were leaving daily, from Wolverhampton for many destinations including Chester, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Holyhead, Newcastle, Bristol, Gloucester and Southampton. However the days of the stage coach were numbered once the railways began to be developed. While the railways heralded the end of the stage coaches, it encouraged the development of the omnibus since the companies boasted that they met every train. Industrial Development The communication developments were taking place at a time when the town's industrial involvement was increasing and Wolverhampton was becoming heavily industrialised. However, the industrial history of the town stretches back to a time prior to the Industrial Revolution. Coal and Iron The earliest record of coal mining in the area was in 1273 at Sedgley and in 1665 Dud Dudley estimated that the area was producing about 25,000 tons of coal a year. By 1750 the area was experiencing the growth of the iron industry and this transformed the coal trade as coal was needed in the production of iron. Canal networks were developed to carry the coal to the furnaces of the Black Country. By 1790 the metal industries of the area alone consumed 845,000 tons of coal and the ironmaster John "Iron Mad" Wilkinson of Bilston was using 800 tons of coal each week. Before the end of the nineteenth century coal production in the area was over 8 million tons a year. However by the twentieth century many small pits had disappeared. In 1709 Abraham Darby succeeded in turning coal into coke for the smelting of iron at Coalbrookdale, and just under fifty years later John Wilkinson introduced coke at his Bradley Furnace at Bilston. He also used steam power to provide the blast for his furnaces and later, with James Watt and Matthew Boulton, he adopted the steam engine in the forge and rolling mill. Wilkinson was a local hero and after his death local people gathered at Monmore Green and awaited the return of his ghost. During the nineteenth century there were over 100 furnaces in regular action in the Wolverhampton area, and after 1856 the Bessemer process for making steel was introduced into the area with new steelworks built by Alfred Hickman in Bilston (later to become part of Stewarts and Lloyds). Tinplate and Japanning Tinplate is sheet steel (mild) coated with tin to prevent it from rusting. By the early nineteenth century Wolverhampton was the most important centre for the making of articles from this material. Sometimes these articles were simply painted a plain colour but "japanned" ware became very popular. Japanning means painting with lacquer and varnishing with a hard varnish (japan). The lacquer was usually black but the goods were decorated with elaborate colourful designs. One useful sideline for the japanners was the production of papier-mâché work which was not really papier-mâché but the pasting together of sheets of special paper to form a hardboard-like substance. These goods were japanned in the same way as tinplate ware. Locks and Keys Wolverhampton is known to have been producing locks and keys as early as 1603 with the best known local firm being that of Charles and Jeremiah Chubb which arrived here in 1818 at 38 Horseley Fields. They had come from Portsea in Hampshire. They prospered and moved to larger premises, the old workhouse in Horseley Fields. In 1847 John Chubb was appointed "patent lock maker" to Queen Victoria. At the time of the Great Exhibition (1851) Chubbs were making 30,000 locks a year without using machinery. Steel toys One curious old Wolverhampton industry was the making of steel jewellery. Dr. Plot who was the first great historian of Staffordshire wrote in 1686 that Wolverhampton made things like buckles, sword hilts and jewellery from burnished steel. In 1770 the first Trade Directory for the town listed 30 "steel toy makers" with "toy" meaning small fashion article or trinket. The trade flourished until about 1795 and one of the best known jewellery makers, John Worralow, was appointed steel jeweller to George III in 1782. By the end of the century, however, cheaper and quicker methods had been devised, especially at Boulton and Watt's Soho Works in Birmingham. Once again there are many interesting examples of the work at Bantock House Museum. Transport Industry Towards the end of the nineteenth century a number of Wulfrunians became closely involved in the fast developing transport industries including: John Marston, his son Charles, the Stevens Brothers.

The Boulton Paul Defiant

After the initial success heavy losses followed; it was then used as a night fighter for some time and later as a target tug. 1064 were built. Since the early 1980's both Perton and Pendeford airfields have been the sites of major housing developments. Twentieth Century expansion

In 1965 it was decided to enlarge the boundaries of several West Midland towns. Thus, in the spring of 1965 five new West Midland towns emerged, Wolverhampton, Walsall, West Bromwich, Dudley and Warley (Sandwell). The population figures for the new Wolverhampton rose to over a quarter of a million. Since the growth of Wolverhampton the redevelopment programme has continued with particular examples being the construction of the Mander and Wulfrun Centres as large, comfortable shopping areas, a large number of new secondary schools and the Civic Centre which has brought the administration of the town back to its beginnings on the site of Lady Wulfruna's Heantun. |

St John's Church was opened for worship in 1760.

Its surroundings are now much changed.

St John's Church was opened for worship in 1760.

Its surroundings are now much changed.

The coal arch at the top of Railway Drive on

Wednesfield Road.

The coal arch at the top of Railway Drive on

Wednesfield Road. Queen Victoria visited Wolverhampton on November

30th 1866 to unveil the statue to Prince Albert. She is shown here

knighting the Mayor.

Queen Victoria visited Wolverhampton on November

30th 1866 to unveil the statue to Prince Albert. She is shown here

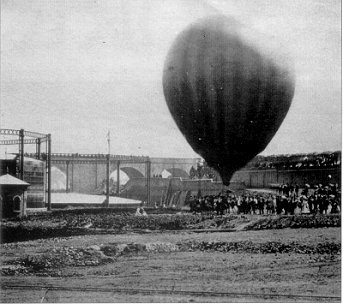

knighting the Mayor. The 1862 ascent from what is now the site of

Wolverhampton's Science Park. Picture by courtesy of Wolverhampton Library.

The 1862 ascent from what is now the site of

Wolverhampton's Science Park. Picture by courtesy of Wolverhampton Library. The Boulton Paul Defiant.

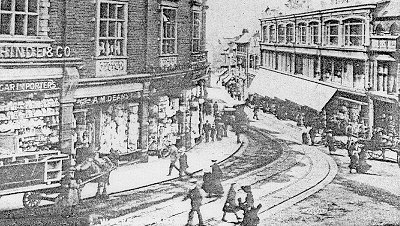

The Boulton Paul Defiant. Victoria Street as it appeared in 1910, looking

down towards Worcester Street.

Victoria Street as it appeared in 1910, looking

down towards Worcester Street.