|

Wolverhampton's Listed Buildings

Low Hill Branch Library

Showell Circus

|

|

|

National Listing: Branch Library.

1930. H. B. Robinson MIMCE [Borough Engineer]. ... The library is

a logical and inspired answer to the requirement for a branch library at

the heart of an estate which was widely admired at the time of its

building. The rooms are filled with day light and at night the

building becomes a beacon. The use of a simple classical style

together with more homely glazing and textured materials gives a feeling

of domesticity and serious intent and provides a formal focus to the

estate without being alien to it.

Local Listing: Wolverhampton's first branch

library, opened in 1930. Landmark quality.

Comment: One of the most distinctive

buildings in Wolverhampton, its remarkable shape fully justified by its

use as a library, and its appearance greatly adding to the interest of

an award winning council house estate. Refurbished in 2003.

Originally the building was locally listed only but was spot listed

nationally on 11th March 2004, mainly on the basis of a report by Duncan

Nimmo. A version of Dr. Nimmo's report appear below.

Duncan Nimmo writes:

Bushbury’s was significant as Wolverhampton’s first branch library,

opened in 1930 after a succession of discussions and abortive proposals

over the preceding decade. Its setting, the Low Hill estate, was

itself significant – a major example of post-War municipal housing,

which attracted some national attention; and the new library was

deliberately sited at its core, Showell Circus. The official

opening was a correspondingly proud event, performed by Sir Charles

Grant Robertson, Principal of Birmingham University.

The architects were the Borough Engineer, H. B. Robinson MIMCE, and his

staff, working closely with the Chief Librarian. The same team was

soon to design the combined Public

Baths and Branch Library at nearby Heath Town, opened in two stages

in 1932 and 1933. This building was listed, at Grade II, in September

2000.

|

|

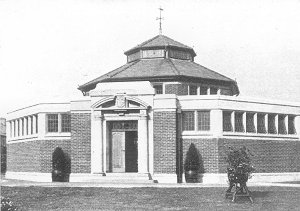

The library at the time of its opening.

|

Both originally and as restored, Bushbury Library

has the same "modernist" traits as Heath Town Baths and Library, and

indeed others of H. B. Robinson’s buildings, for instance his Park

Lane Welfare Clinic of 1931, and Elston Hall primary school of 1938,

now on the City’s Local List of notable buildings.

Among these traits are a stylish plainness, an

emphasis on the horizontal, this being highlighted by the

combination of brick and stone, and the occasional use of flat

as well as pitched roofing. |

| However the most prominent shared trait is

geometrical symmetry, here of an extreme and striking kind.

The shape of the library is an octagon, repeated in three stepped

tiers: a bold and imaginative conception, producing what may well be

judged one of the city’s most remarkable small buildings. The

sources for this application of Robinson’s characteristic

symmetrical geometry invite speculation. It is reminiscent of

some contemporary London Underground stations. |

Park Lane Welfare Clinic at the time of its

opening.

|

|

The Library from the east, showing the

lantern shape.

|

There could however be a specific local influence, in that the layout of

the Bushbury estate is itself largely geometrical and symmetrical.

Suggestively, the Chief Librarian’s account of the opening

includes the remark "The building is erected on a central site,

and roads radiate from this point, the whole scheme having

been designed to give a like elevation from whichever angle it

is viewed" (italics added). |

|

Perhaps even more intriguing is the following comment, "At night it is a

beacon light, and its illumination across this vast estate is a picture

worth seeing"; for this may help explain the second key design feature

after the octagonal plan, namely the 3 stepped tiers. This element was

of course an architectural commonplace, recently rejuvenated with the

concrete parabolic arches of the Royal Horticultural Hall, and it is

noteworthy that that model was to be adopted at Heath Town baths just

two years later.

A prime purpose of stepped tiers is to admit maximum natural

light, and that was doubtless one goal here; contemporary

opinion stressed the desirability of natural light in libraries,

witness for example K. M. B. Cross’s article "Public Libraries

and their Planning" in "Architecture" of September/October 1931. |

The interior, showing the natural lighting.

|

|

Natural light reaches in everywhere.

|

But may Robinson’s design not also have aimed at

the opposite, less obvious effect – for the Library to shine out in

all directions over the surrounding estate? In that case, we might

conclude that the fundamental inspiration for the striking design of

the building was, as the whole of the Librarian’s account conveys,

to act as a beacon of light, cultural but also physical, for the new

and experimental community around it. Deliberately or

otherwise, this would be a perfect realisation of the Borough’s

motto: "Out of darkness cometh light". |

| Whatever its sources, there is no doubting the

originality of the Library design for its place and period.

This is brought out by comparison with two neighbouring contemporary

buildings, the Methodist Church of 1929, and the adjacent Community

Centre of 1937. |

The Methodist Church.

|

|

The Community Centre. |

Despite features characteristic of the period, neither matches the

imaginative quality of the Library. |

|