|

.JPG)

Listing: Grade II*. 1860-1. By G. T. Robinson of Leamington.

Roguish Gothic Revival style. A good design making use of polychrome and much

use of cast-iron, with some remarkable roguish details.

Pevsner: "[Robinson] could evidently be what Goodhart-Rendel called a

rogue architect. The church is furiously unruly. Red brick with yellow and black

brick, SW steeple with a highly fanciful spire. Windows with plate tracery. But

the clerestory windows are spherical triangles filled with roundels. Polygonal

chancel. Inside, the piers are of iron, thin and doubled - longitudinally, not

transversely. Who in the name of reason would do that?"

Comment: The church was

restored and the exterior cleaned a few years ago, so that it makes a bright and

cheerful adornment to an area, still mainly of small factories and small houses,

which might otherwise be visually dull. Its setting is now made livelier by the

golden domes of the Sikh Temple nearby, so that the whole thing would surprise

the critics even more. Good.

The following full account of the church and its history was

originally prepared as part of the ABCD Heritage Project and we are

grateful to the author for permission to reproduce it here.

St. Luke's Church,

Blakenhall

by Martin Rispin

Introduction

.JPG) |

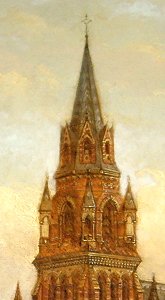

The impressive spire of St. Luke’s

(Church of England) Church has towered over Wolverhampton

since 1861. But it is not only

its height, at one hundred and seventy feet, that makes it

such a city landmark - the building’s distinctive and

unusually colourful Gothic Revival architecture marks it out

as being of national architectural importance, meriting a

statutory Grade II* listing in 1992 from the Department for

Culture Media and Sport/English Heritage. |

Architect

The church was designed by

George Thomas Robinson c.1827-1897, who was described by the famous

architectural historian Sir Nikolas Pevsner as a ‘roguish architect’.

Pevsner goes on to say of St. Luke’s, in his ‘The Buildings of England’:

“The church is furiously

unruly. Red brick with yellow brick and black brick. South west

steeple with a highly fanciful spire. Windows with plate tracery.

But the clerestory windows are spherical triangles filled with

roundels. Polygonal chancel. Inside, the piers of iron, thin and

doubled – longitudinally – not transversely. Who in the name of

reason would do that?”

Form

The church is laid out in a

traditional style on an east-west axis so that the altar points towards

the Holy Land. There is a nave, with side aisles to both the north and

south, a chancel with an apse and a separate small side chapel at the

end of the northern aisle. There is also a narthex (an entrance lobby)

at the western end.

| An early painting, in the

possession of the church, showing St. Luke's and its

schools. |

|

The bell ringing chamber, bell

chamber and steeple are accessed by a spiral staircase which opens from

a door in the churchyard at the base of the tower, but beyond the bell

ringing chamber access is by ladder only.

.JPG) |

Left: the spire now, with no

mini spires but with a clock.

Right: about 1770s, with mini

spires but no clock. |

|

An early painting of St. Luke’s

Church, circa 1870s, shows small ‘balconies’ at each corner of the tower

just below the level of the clock faces with pillars rising from blocks

in front of them, each ending in its own mini spire.With the four mini

spires the impression would have perhaps more closely merited its

attribution as the work of a ‘roguish architect’. These mini spires

were removed in 1967.

Design

Externally the church is a riot

of polychromatic brick (mosaics of different coloured brickwork)

highlighted with stone, all set out in elaborate geometric patterns.

When first built the church would undoubtedly have looked even more

colourful than it does today, if not a little garish, before the colours

of the bricks had mellowed to their current more muted shades. The roof

originally was also laid in geometric patterns using different colours

of slates, now alas, all plain coloured replacement slates. The cast

iron rainwater fall pipes were formerly laid in straight lines across

the pitch of the transept roofs and would have added to the strong

horizontal and vertical lines of the overall design.

Church Foundation and

Dedication

.JPG) |

The church’s foundation stone is

located at the south west corner of the building and was

laid by the Reverend William Dalton on 26th June

1860. |

The bricks were actually made on

the site, not least because a brick yard occupied it before the church’s

construction. The church was completed in 1861 and consecrated on 18th

July of that year.

| Painted plaque inside the church

recording the grant of £500 towards the building and the

provision of free seats. |

.JPG) |

Although Blakenhall was a rural

backwater in the 1860s (as can be seen in the painting) it quickly

developed into the hub of the early British automotive industry; but the

wide scale residential developments that the church was expected to

serve never really materialised.

Churchyard and Exterior

The churchyard has never been

used as a burial ground, as the church was built after Wolverhampton’s

purpose built Merridale Cemetery, and so is laid to grass with tarmac

pathways with mature shrub and plant borders. There is also now a

modern parish hall, dating from 1967, within the churchyard which

replaces an earlier more elaborate Victorian structure that was

demolished in 1964 when it was declared structurally unsafe.

Notable external features

include:

.JPG) |

The church yard walls at the south

and west and their gate piers, which are decorative and

statutorily listed Grade II in their own right, broadly

mirroring the exterior of the narthex. |

| The main vehicular entry gates were

dedicated in 1961. |

.JPG) |

.jpg) |

The sculptural panel above the south

west doors depicts St. Luke writing his gospel. |

| The sculpture above the north west

door, that leads into the narthex, is of Christ with two

disciples on the road to Emmaus. |

.jpg) |

The four faced clock was

added to the steeple in 1874, donated by local businessman Edward Lisle

who also gave the peal of eight bells in 1897 to celebrate Queen

Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee (sixty years on the throne), replacing the

single original bell that was cast by G Mears & Company of London and

installed in 1861.

There are a number of plaques

within the church (not all on display) commemorating various bell

ringing events at St. Luke’s Church.

Interior

.JPG) |

Inside the church worshippers and

visitors get an immediate sense of both height and light

with surprisingly little mirroring of the ‘furiously unruly’

exterior although some of the same types of design are to be

found but somewhat scaled down. However, a lost feature

that would have been controversial if still in situ

was a Minton tiled floor along the central aisle of the

nave, which may have also extended to the chancel; this was

a tiled mosaic design in the same tones as the exterior

patterned brickwork but set out in swastika patterns (these

of course having none of the 1930s fascist associations when

fitted in the 1860s). This has been replaced with a

terrazzo floor surface now covered with carpet tiles but the

central aisle can clearly be seen in a painting kept in the

vestry. Commemorative plaques show that the chancel had been

re-laid in marble by the late 1920s. |

Narthex

| The narthex, formerly semi-open but

now with the tracery arches glazed and part partitioned off

for other uses, contains a commemorative plaque detailing a

donation of £500 to the building of the church to provide

free seats for poorer inhabitants of the parish (at the time

of building pews were still rented by wealthier parishioners

for their own exclusive use). The central pillar on the

narthex side of the west door is painted to look like wood

but is in fact cast iron like all the other pillars in the

church. |

.JPG) |

Nave

.JPG) |

The nave has six bays

again supported on cast iron columns, like the chancel’s,

with trumpet shaped capitals which form the springboard for

polychrome brick arches (not perhaps as colourful as the

outside brickwork) with plastered brick infill between,

pierced by three rounded triangular windows to each side and

with two west windows and a roundel above. |

.jpg) |

| The roof has a very deep arch-braced

scissor truss, all now painted, which adds to the

lightness.

The nave also bears two painted bible

verses at high level (John 4v24 & John 14v6) which

characterise the ministry and worship at St. Luke’s.

|

.jpg) |

The nave and side aisles are

occupied by original pews to match the architecture, although the rear

five rows were removed during the millennium to allow a more flexible

space for the congregation to meet before and after services and to

allow for the construction of enclosed crèche and kitchen facilities.

Contained within the nave are

the lectern, the pulpit and the font.

|

The brass lectern was presented in

1907 by the congregation in memory of the long ministry of

the vicar William Thomas Milligan who was to continue for

another six years. (In this postcard of the

lectern, from about 1907, can also b seen the paintings

which were once on the walls each side of the altar) |

| The pulpit is in memory of the first

vicar John Parry whose ministry at St. Luke’s was from 1861

to 1882 although it was presented by his widow in 1909 and

was originally located at the rear of the nave. It is

supported on three stone shafts and bears panels on each of

its four sides depicting the gospel writers Matthew, Mark,

Luke and John. |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

The font is in front of the side

chapel, octagonal in form, supported on one large and four

smaller shafts of stone. |

| On the walls of both aisles are commemorative plaques

for different people but all of the same design.

Ceramic plaques such as this are not unusual in

Wolverhampton churches but these may not be ceramic and may

be unique to this locality. |

.JPG) |

Chancel

At the eastern end of the church

is the three bayed chancel which contains the Communion Table and choir

and clergy stalls (the carved oak table, with eight winged angels, was

donated in 1929 and stalls and communion rail donated in 1918). The

original plainer Communion Table is now to be found at the rear of the

Nave.

.JPG) |

The bays of the chancel are supported

on paired cast iron columns (arranged transversely and not

longitudinally) atop stone piers and the tracery screen

within each bay is now glazed; |

.jpg) |

Above there is a

panelled scissor truss roof supported on twelve carved stone

brackets in the form of heads representing the twelve

Apostles. |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

The Communion Table is surmounted by

rich arcading and the reredos behind it has a deeply carved

relief of The Last Supper, presumably by the same sculptor

as the panels above the external doors. The east window

above the altar, like the others in the chancel is in

stained glass. |

The War Memorial Chapel &

Organ

Between the chancel and nave is

a tripartite, or triple formed, arch; to the north of this is a side

chapel, created in 1920, divided from the side aisle by twin arches and

to the south the 1923 organ also divided from the side aisle by twin

arches. An impression of the church’s original gothic revival decorative

scheme can be gained by looking at the painted organ pipes above the

organ’s keyboard; those fronting the nave have been repainted plain

silver. The side chapel, as it is known, is dedicated to the memory of

one hundred and eleven parishioners who fell in both World Wars. It

also contains a stained glass window that was erected in memory of

William Thomas Milligan who was vicar from 1889 to 1913. Below the side

chapel is the boiler room (originally coal-fired).

Vestry

The Vestry is not open to the

public but houses an interesting collection of framed portraits of

former vicars from 1861 to the present day as well as oil paintings

depicting the church interior as it originally was, including the

swastika design tiled floor, and another showing the exterior in its

original rural setting complete with patterned roof and ‘minarets’.

There is also an old sepia photograph (pre-1909) which shows other lost

features, including paintings at either side of the altar, decorated

finishes around arches and windows (see the organ pipes above the key

board for an impression of the style and colours of this decoration),

large brass gasoliers, gilding on roof trusses but the cast iron pillars

apparently either unpainted or dark coloured.

|

This postcard, posted in 1911,

also shows the decorations around the arches and, almost in

line with the pillars, the brass standard gasoliers. |

St. Luke’s School and

Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club

|

A postcard of about 1920 showing

typical houses of the area, the school and the church. |

The original St. Luke’s School was designed by

architect Edward Banks who flourished 1842-1874.

| This was in a broadly similar style

to the church and was located within the churchyard fronting

Lower Villiers Street behind the low undecorated boundary

wall (a small disused gate can still be seen behind within

the hedge). But this building

had been demolished by the 1970s and is now relocated

further back within the site, although this replacement is

in turn possibly to be re-used as the school is relocating

in 2009 to a site nearby. |

|

.jpg) |

Pupils and staff from the original

school, notably Headmaster Harry Barcroft and pupils John

Baynton and Jack Brodie, were involved in the establishment

of Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club in 1877 although

the club was originally known as St. Luke’s Football Club.

Wolves went on to become one of the

twelve founder members of the English Football League in

1888 and to win the Football Association Cup on four

occasions in 1893, 1908, 1949 and 1960. |

| This details from the painting

shown above, shows haymakers on the field where St. Luke's

(or Wolves) are supposed to have practised; and where later

Villiers and Sunbeam factories stood. |

|

|