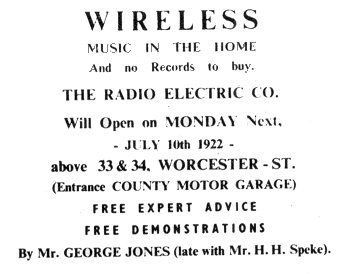

| The Radio Electric Company opened for business on

10th July 1922, as can be seen from the advert. The premises were on

the eastern side of Worcester Street, in between Temple Street and

Church Street. The advert includes a reference to Mr. H. H. Speke,

the chairman of Wolverhampton's first amateur radio society, the Wolverhampton and District Wireless Society. The

society's first

meeting took place on 1st March, 1922.

Mr Speke had a shop at 26

King Street, in which he sold models, toys and books, and later

ex-army and navy surplus items. |

|

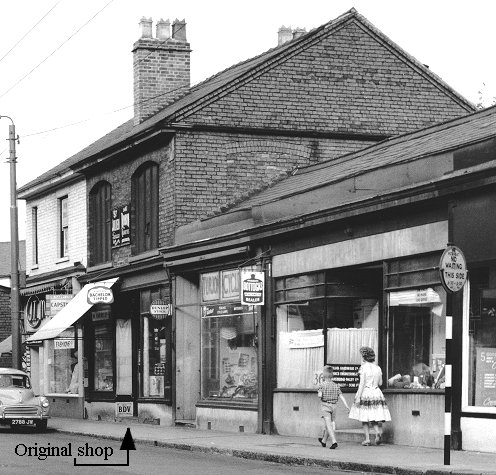

| The company's first shop at 33 and 34

Worcester Street. As seen in 1961

when it was occupied by a tobacconist.

Photo courtesy of John Hughes. |

|

| The Radio Electric Company was started by George Jones, the

Secretary of the Wireless Society who had the call sign 2WB. He

had previously worked for Mr. Speke in King Street. When he

started the business he relinquished his secretarial duties due

to pressure of work. Within six months the business had moved to

a shop in St. John's Street. |

A map showing the location of the Radio Electric

Company's shop in St. John's Street. |

Mr. Jack Rushton was an amateur radio enthusiast with the

call sign 5LK. Jack had a shop at 17 Victoria Street called 'Radio,

Motors and Cycles Limited' (marked in orange on the map), where

Halfords used to be. There was a link between Jack Rushton's

business and the Radio Electric Company, because Jack's

name was included on the Radio Electric Company's letterheads.

The two shops were also linked by a connecting yard at the

back. A redirected envelope dated April 6th, 1923, found in

the personal records of the late George Jones suggests that he

may have left the business by that time.

|

| At St. John's Street, Mr. Creed worked in the shop and

George Berry, the son of amateur radio enthusiast, H. Berry, who

had the call sign 6PB, was employed to build wireless sets. The

cellars below the shop were used to charge accumulators, which

in those days were an essential part of any valve receiver.

The

St. John's Street shop was situated on the corner, where the

street turned sharply to lead alongside the old Mander's

works. Also on the staff were Mrs Creed and Mr. C. Fenwick. Mr.

Creed later became manager of the 'Radio, Motors and Cycles'

shop in Victoria Street, where receivers were constructed by

Arthur Shaw, who was Mrs Creed's brother. He built quantities of

a popular domestic crystal set which sold for seven shillings

and sixpence. |

An advert from 1924. |

|

A photograph taken outside the St.

John's Street shop with Jack Rushton and the staff in the

background. |

|

When the Wolverhampton and

District Wireless Society ceased to exist, it was replaced by

the Wolverhampton & District Transmitters' Society, members of

which used to meet in the Radio, Motors and Cycles' shop and

also in the Radio Electric Company's shop in St. John's Street. During 1925 'Radio, Motors and Cycles Limited' had either

joined forces with the Radio Electric Company or been taken over

by it, as can be seen from the advert above.

By the middle of the year, the Victoria Street Shop traded as

part of the Radio Electric Company, which also had premises at

Church Street, Bilston. Presumably another shop.

|

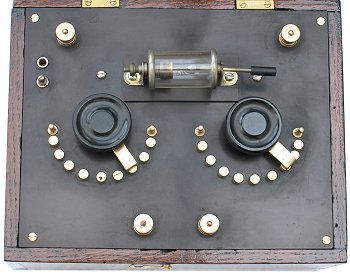

A crystal set made by the Radio

Electric Company in possibly 1923 or early 1924. |

| In the 1925 Wolverhampton Red Book, the Victoria Street

premises is listed under the name of the Radio Electric Company,

but both the 1927 and 1930 Red Books list it as Radio, Motors

and Cycles Limited, so both names continued to be used. In 1930

the business closed, and the Victoria Street shop was taken over

by Halfords. When this happened Arthur Shaw started his own

radio business in Queen Street, and Mr. C. Fenwick opened his

radio and components shop at the eastern end of Great Brickkiln

Street (now Pitt Street), which many people will fondly

remember. Next door he had another shop selling fishing tackle,

toys, models, and guns. |

|

An advert from 1925. |

|

Jack Rushton. |

A Radio Motors and Cycles receiver

from 1925. |

|

An advert from 1925. |

An advert from 1925.

An advert from 1925.

An advert from 1925 which

shows the 2nd floor room above the Victoria Street shop where

meetings of the Wolverhampton and District Transmitters Society

were held. |

|

An advert from 1926.

|

The advert on the left confirms that the Radio Electric Company produced valve receivers, rather than just crystal sets,

which may have been identical to the receiver described in the

Radio Motors and Cycles advert above. Maud Highfield worked in

the Victoria Street shop and remembered Jack Rushton as an

enterprising man and a very good business man.

She remembered a workshop at the back of the Victoria Street

premises, and an open space, which came out into John's Street

where Jack Rushton sold caravans. He also had a room above the

Central Arcade at the lower end, where he employed two girls to

make radio sets. In the cellar of the shop was a strong room and

a place where coal was kept, and the area where batteries were

charged. Two ladies came in to light the coal fires in the shop

every day.

Burroughs adding machines and Gledhill tills were used in the

shop which had beautiful display cases. Items for sale included

Parlophone and Eddison Bell records, Cosmos, Philips, Ecko and

K.B. radios, radio components, Ariel and Douglas motorcycles,

and Rudge bicycles.

|

| In the photograph opposite, the top two terminals are aerial and earth

respectively and the bottom terminals are for headphones. The

two switches are for tuning. The one on the left is coarse

tuning and the one on the right, fine tuning.

The plug and socket on the far left is for the plug-in Medium

or Long Wave coil.

A Long Wave coil would have certainly been desirable after

the opening of the BBC's Daventry transmitter in 1925. |

Another view of the Radio Electric

Company's crystal set. |

Circuit diagram of the crystal set made by the

Radio Electric Company.

| The receiver is extremely simple. The tuned circuit consists

of a plug-in coil in series with a much smaller tapped and

switched inductance, which is used for tuning, along with the

self capacitance of the coils. Coarse and fine tuning is

possible by the positioning of the taps on the coil. The fine

tuning switch increases or decreases the inductance in smaller

steps than the coarse tuning switch.

The aerial is connected directly across the tuned circuit.

Although this will effect the tuning and the selectivity of the

receiver, it is of no great significance because the tuned

circuit will already be heavily damped by the cat's whisker and

headphones. Like the aerial, the cat's whisker and headphones in

series are connected directly across the tuned circuit, which

was normal practice in such a simple design.

This is clearly a simple and cheap receiver, aimed at the

bottom end of the market. It's performance is poor, but it would

have been affordable to almost anyone and so would have helped

to bring radio to the masses, at a time when valve receivers

were still very expensive. This may well be one of the crystal

sets that were sold for just 7s.6d. |

| The inside of the receiver showing

the crude form of construction. The coil is home-made and wound on a

large cardboard tube. |

|

|

An overall view of the receiver

showing the oak case. |

| The licence plate that's mounted

inside the cabinet lid. The low registration number suggests that it was

made soon after the formation of the BBC in 1923. |

|

|

A close-up view of the cats

whisker. The handle on the right allows the cat's whisker to be adjusted

to make contact with a suitable spot on the crystal. |

| Another view of the

receiver, complete with plug-in Medium Wave coil. |

|

|

|

A final view of the receiver, complete

with plug-in coil. Although this is a bottom of the range

receiver, it is still nicely finished. |

| Pieces of crystalline material for use

in the receiver. The crystal is often a small piece of galena

(lead sulphide), although other materials were used.

In the receiver the cat's whisker is

enclosed in a glass tube to exclude dust. The crystals are quite

soft and will soon wear as the point of cat's whisker is dragged

across the surface, so replacements were essential. |

|

| J. V. Rushton Jack Rushton

was a man of many talents. He lived at 134 Mount Road, Penn, and

became an accomplished pilot of light aircraft and trained glider

pilots. He also experimented with magnetic wire recording, to record

pictures and send them by radio and wire. He made improvements to

storage batteries, including a failed attempt to produce a

lead-aluminium battery, during which he developed his own method of

anodising aluminium.

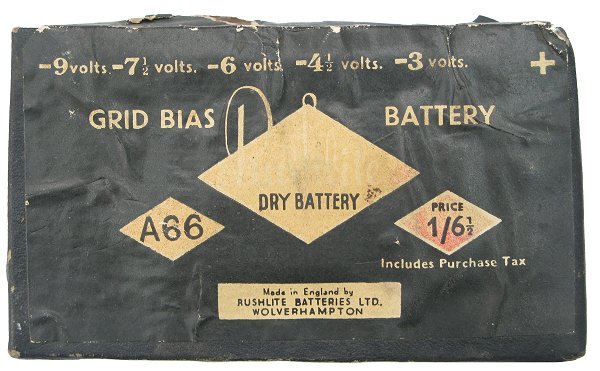

After the closure of the Radio Electric Company, Jack began

producing 'Rushlite' dry batteries at Rushlite Batteries Limited

in Temple Street, Wolverhampton, and sold many during World War 2

when batteries were in short supply. Battery production continued

until about 1955. From 1956 onwards the business ceased to be listed

in the Wolverhampton Red Book. |

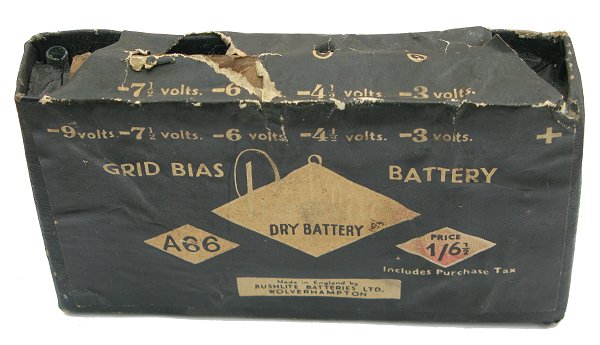

A 'Rushlite' battery.

Another view of the 'Rushlite' battery.

| Jack continued to be actively involved in amateur radio. He

became a honorary member of the Wolverhampton and District

Transmitters' Society, and was society president from 1924 until

1934. 1946 saw the formation of the Wolverhampton Amateur Radio Society.

Jack became society president in 1947, and remained in post until 1964.

By the 1930s Jack had become a proficient pilot, who greatly enjoyed

gliding. He was involved in the formation of the Midland Gliding

Club on the Long Mynd in Shropshire, and in 1930 was club

secretary. On 24th July, 1937 he won the Volk Cup for the longest

duration flight during the previous twelve months. He received the

cup for a flight of eight hours in a glider at the Midland Gliding

Club. In the same year he competed in the National Soaring Meeting,

flying a Grunau Baby II. In the Second World War he put his flying

experience to good use, training glider pilots. |

|

An advert from 1939. |

Jack Rushton had a number of business interests. He ran J.V.

Rushton Limited based at Anodic Works on the Birmingham New Road in

Wolverhampton. The firm specialised in electroplating, anodising,

chrome plating, general metal finishing, and hardening, particularly

for the aircraft industry.

The company was founded in 1936 and soon expanded and opened

other factories:

1937 - J. V. Rushton (Birmingham) incorporated

1937 - J. V. Rushton (London) incorporated

1941 - J. V. Rushton (Coventry) incorporated

1941 - J. V. Rushton (Redditch) incorporated

Jack also owned the Coventry Chromium Plating

Company.

|

|

The edition of Flight magazine published in

April 1937 includes the following brief article:

J. V. RUSHTON (LONDON), LTD., was registered as

a private company on March 10 with a nominal capital of £5,000 in £1

shares.

Objects : to construct and work plants for anodising, more particularly to

Air Ministry specification, in association with J. V. Rushton (Wolverhampton).

Ltd., and J. V. Rushton (Birmingham), Ltd. (when incorporated), and

generally for the protection and colouring of aluminium and its alloys; to carry

on business as anodisers, metal finishers, depositors and sprayers, etc.

The

subscribers are John V. Rushton, 134, Mount Rd., Penn, Wolverhampton, anodic

oxidation chemist; and Mrs. Florence Rushton. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

From 'The Aeroplane', February 7th, 1941. |

|

| By 1946 the companies had been taken over by Midland Holdings, a

holding company for what was possibly the largest group of electroplaters, anodisers, and

metal finishing businesses in the country. It had plants in

Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Coventry, Manchester, Newbury, Cardiff,

and Scotland. Jack Rushton was also a Rotarian. The following

article written by him appeared in the April 1951 edition of The Rotarian: |

|

What Freedom Would We Lose?

J. V. Rushton, Rotarian

Past Service

Wolverhampton, England

At one time people feared only the weapons in

the hands of their opponents. Now progress has made modern weapons a

danger to all. This year the world is spending

considerably more than 10,000 million pounds on preparing for war;

only a fraction of this amount would be necessary to support a world

force to maintain world peace. What freedom would we lose if we

surrendered our armed strength to such a world force? Individually

we would probably find ourselves with much more freedom, freedom to

travel and trade in any part of the world - a world without

frontiers; and even more important we would be free from the fear of

war.

I think that if America and England were to

declare that they were willing to surrender their forces to a world

government, other countries would rapidly follow suit, because I

believe that the people of every country of the world are scared of

war and that they know that behind all their bluff there is no other

way of avoiding it.

|

|

| Jack Rushton left the West Midlands and retired to the

Channel Islands. |

An advert from 1944.

| The information on the Radio Electric Company company was obtained from 'Wireless

In Wolverhampton', published by the Wolverhampton Amateur Radio

Society in 1972. If you have any further information about the

company, or its products, please

send me an email. |

|

Return to

the list of manufacturers |

|