|

Bicycle Development

Bicycles were developed from the

hobby-horses and velocipedes that appeared in France in the late 1770s.

The early machines were heavy, cumbersome, totally impractical, and were

basically toys for the wealthier members of society. In the early 1800s

Nicephore Niepce, an early photographer, built a machine that could be

steered and ridden, but much development was still necessary before the

machine could readily be used.

Around 1817 Baron

Von Drais, a wealthy German engineer, constructed a hobby

horse with an easily steerable front wheel, padded saddle

and an armrest that enabled the rider to give powerful

thrusts with his feet. The rider sat astride the vehicle

with both feet reaching the ground and propelled the machine

with a running action. Considerable numbers of the machines

were made and they became known as Draisiennes and speeds of

7 or 8m.p.h. could be easily be attained. The manufacturers

optimistically claimed that an average speed of 15m.p.h.

could be achieved on a journey, but this could be dangerous

to say the least considering the conditions of the roads at

the time. The Draisiennes weighed about 50lbs and cost

around £11, and so were very expensive at the time.

The next breakthrough in the development of the modern cycle was the

invention of pedals and cranks. Cranks first appeared on a quadricycle

in around 1819, but the first application of the crank to a bicycle was

made by Scottish blacksmith Kirkpatric McMillan in 1839. He built a

machine that used fore and aft cranks rather than rotary ones and this

became the first practical hobby horse. |

|

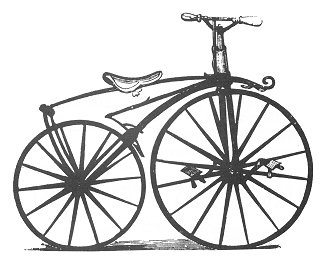

A French style

bicycle. Courtesy of the late Jim Boulton. |

Pedals didn’t appear until 1860 when

a maker of pram wheels in Paris fitted pedals and a crank to

the front wheels of his hobby horse.

There were many claims as to who was first to achieve this

breakthrough, but it is generally accepted that either

Pierre Michaux or one of his mechanics made the first

prototype. Michaux soon began producing the machines that

were known as Velocipedes. They had wrought-iron frames,

iron-tyred wooden wheels and weighed between 80 and 100lbs.

They were extremely heavy and uncomfortable to ride and

became known as “Boneshakers”. |

| They were a great improvement on

anything that had been produced before except for the now

forgotten McMillan machine.

Velocipedes were first exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of

1867 and soon versions were built in the UK. An early

manufacturer was the Coventry Sewing Machine Company, whose

representative, Rowley B. Turner visited the Paris

exhibition and persuaded the company to produce machines for

export to France. Whilst in Paris he purchased a machine, as

did Charles Spencer and J. Meynal, and they rode them from

London to Brighton, much to the interest of the general

public. |

| Mr. Turner obtained an order from a

Paris house for 500 machines and the Sewing Machine Company

obtained suitable machinery and plant for their manufacture.

They also made many improvements to the

original design and changed the name of the company to the

Coventry Machinists’ Company Limited.

The venture ran into difficulties due

to the Franco-Prussian War and so the machines were sold on

the home market. |

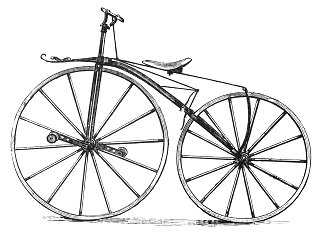

An early English bicycle.

Courtesy of the late Jim Boulton. |

| Sales were high and other

manufacturers soon appeared, mainly consisting of

blacksmiths and coach builders, and large numbers of

machines were made until the appearance of the bicycle in

about 1870. |

|

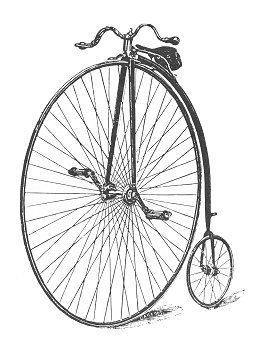

A penny farthing. Courtesy of the

late Jim Boulton. |

The first successful bicycles, known

as the “Penny Farthing” or the “High Wheeler” were a great

improvement on the “Boneshakers”. The front wheel was

greatly increased in size to produce a higher speed machine,

because a greater distance could be covered for each turn of

the pedals. At the same time the rear wheel was reduced in

diameter and solid rubber tyres were soon used along with

lightweight steel instead of heavy iron frames.

Front wheel diameters increased from 50 or 54 inches to 62

or even 64 inches for the fastest racing machines, placing

the rider a great distance from the ground. A fall could be

a serious thing, especially when going at speed and such

mishaps became known as “headers” or “imperial crowners”.

The brakes were inefficient, making stopping difficult, and

the bicycles were difficult to mount and dismount. They

could however cover long distances at speed and so became

very popular. |

| There were other alternatives for

those who preferred a lower machine. “Penny Farthings” were

not suitable for women who found them impossible to ride due

to the long skirts and dresses that were worn at the time,

and also children, whose legs couldn’t reach the pedals.

Tricycles satisfied their needs and many and varied types

were produced. Unfortunately they could easily run away on

hills or overturn. Something better was necessary and the

answer to the problem was found in rear wheel drive and

gearing. Up

until now all machines had front wheel direct drive, which

resulted in steering problems because the rider’s legs were

in the way. In September 1879 the modern type of bicycle

called the “Safety” bicycle was patented by John Lawson. It

had a small front wheel and a larger rear wheel with a pedal

and chain drive. From now on the “Penny Farthings” were

known as the “Ordinary” bicycle and would soon become a

thing of the past. The first really practical bicycle with

equally sized front and rear wheels was developed by John

Kemp and William Sutton in 1885 and built at Coventry using

the name “Rover”. The new machines became very popular and

large numbers were sold.

Another important

development was the appearance of pneumatic tyres. They were

originally invented by R.W. Thompson in 1845 but little

interest was shown until John Boyd Dunlop, a veterinary

surgeon of Belfast developed them for cycle wheels in 1888.

The Dunlop tyre initially consisted of an airtight inner

tube of indiarubber, covered with one or more canvas

coverings for protection. This was soon developed into the

Clincher tyre which allowed repairs to be easily made.

Modern looking

bicycles appeared in 1890 with the invention of the diamond

frame, thanks to Thomas Humber, and reliable variable gears

were available in 1902. All of the major components of the

modern bicycle were now in place and large numbers of

companies produced them. Ladies cycles were quickly

introduced and the industry rapidly grew with demand far

outstripping supply. Large numbers of small manufacturers

appeared to take advantage of the new market, but the bubble

quickly burst and many of them soon went into liquidation,

loosing vast sums of money in the process. Luckily the well

established companies survived and prospered to employ

thousands of men and women in a growing vehicle industry

that centred on Coventry, Nottingham and Wolverhampton.

Lighting

The first cycle lamps appeared in the

late 1860s and were sold as extras for the bicycles of the

day, which were known as velocipedes. Roads at the time were

very poor, often consisting of a dirt track with many pot

holes, and street lights were few and far between, making a

lamp essential when riding after dark.

Early lamps consisted of candle lamps and oil lamps. Candle

lamps contained a candle in a spring loaded tube, which

pushed it up as it burned. This form of lighting was never

popular with the cycling public because it gave very little

light and would be blown out in the lightest breeze. The

lamps did however have a limited success with lady cyclists

because they were clean.

Candle lamps soon disappeared due to the far superior oil

lamp, in which paraffin or coal oil was burned on a clean

open-weave wick, to allow for a good capillary action. By

1882 mechanical or winding wick holders were in use, to

allow a greater degree of flame control and oil consumption.

The lamps were very popular and continued in use until the

1950s.

Two oil lamps from 1896.

In 1892 Canadians Willson and Moorehead

discovered a method of producing Calcium Carbide in an

electric furnace. If this was added to water, acetylene gas

was produced, which when lit gave a brilliant white light.

This was quickly applied to bicycle lighting, and the

carbide lamps produced a very powerful light source. Inside

the lamp, droplets of water fell onto the calcium carbide

that was contained in a small bowl, and the gas produced was

usually burned in front of a reflector. The rate of water

flow could be adjusted by a small screw valve, which

controlled the rate of gas production and the size of the

flame.

The lamps were only popular with enthusiastic riders because

a disagreeable smell was emitted, and the calcium hydroxide

residue, which was left behind in the bowl, had to be

frequently removed. It was also difficult to keep the filter

and burner free of dust. Carbide lamps continued to be

advertised until the late 1930s but their popularity

remained with the old school of cyclists and the dedicated

clubmen.

Electrically powered cycle lamps appeared in 1888 when

Joseph Lucas of Birmingham produced a

rechargeable accumulator powered cycle lamp. It was very

expensive, sales were poor, and by 1889 it had been

discontinued. By 1893 other similar lamps appeared and the

first dynamo-powered cycle light was introduced in about

1895. Two of the most successful products were the

“Voltalite” and the “Dynolite”, which appeared in 1899. At

the same time in America the Ever Ready company were

producing battery powered lamps with a wooden case. Their

familiar pressed steel cycle lamps appeared in 1900 and

remained much the same until recent times.

Wolverhampton's Cycle Industry

Wolverhampton’s

cycle manufacturing industry has almost been forgotten.

There were many manufacturers in the town, which during its

heyday was the third largest bicycle manufacturing centre in

the country. The town was an obvious candidate for the

setting up of the industry thanks to the large numbers of

skilled metal workers in the area and the entrepreneurial

skills of the local manufacturers, who were always willing

to fill a niche in the market.

There are two claims

to the first cycle that was produced in the City. The least

reliable was made by T. Johnson of 18 Peel Street, who

possibly built a machine in 1859. The more reliable of the

two is from Henry Clarke who built a tandem tricycle in

between 1855 and 1860 with the help of a Mr. Panter. Having

built the machine they rode it around the neighbourhood,

much to the astonishment of onlookers. |

|

Henry Clarke saw velocipedes in

Paris during his return from the Crimean war and began to export wooden

velocipede wheels to France in 1867 to 1868. At the same time he started

producing machines under the name of Cogent, which later became the

Wearwell cycle company. This was the longest surviving manufacturer of

bicycles in the town, producing them for just over 100 years.

After the

introduction of the iron tyre Mr. W.S. Lewis of Cleveland

Road, Wolverhampton developed a wheel with a concave rim so

that a solid cord of indiarubber could be fixed onto the

tyre to give a more comfortable ride. |

Henry Clarke |

|

In the 1870s the town was famous

for the bicycle races that took place in the grounds of the Molineux

Hotel, on the site that is now occupied by the football ground.

Large numbers of

spectators came from all over the country to watch the

events that attracted the best riders of the day. The

popularity of the races must have greatly encouraged some of

the early manufacturers.

|

Read about

bicycle racing |

Wolverhampton also produced the

‘Rolls Royce’ of bicycles in the Sunbeam. John Marston who founded the

company, was a perfectionist, always striving for the best. His machines

were second to none, and the company was very successful. Our largest

manufacturer, Viking, had a successful racing team and large numbers of

machines were sold thanks to their many successes in competitions and

trials.

Many of the manufacturers were very

small. All of the necessary components that were needed to

build a bicycle were produced locally, and a number of

producers specialised in supplying parts to the trade. Some

of the smaller manufacturers assembled machines from the

readily available components and only required a small

workshop with maybe one or two employees.

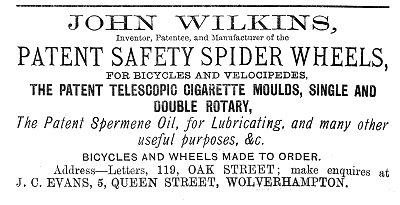

A typical manufacturer who sold parts to the

bicycle trade. Very few details of many of

the smaller companies have survived; often all that is left is adverts

in old trade directories. So the information in this section is

very patchy, to say the least. Many of the local cycle shops also made

bicycles to order, assembling them from the parts that were in stock.

|

View a list of

local bicycle manufacturers |

By 1972 it was all over. The last factory to close

was ironically one of the first to open. Wearwell closed their Colliery

Road works in 1972, after 104 years of bicycle production. Almost all

traces of the industry have disappeared although several of the old

factory buildings still remain. Hopefully future generations will

remember that Wolverhampton was once a force to be reckoned with in the

bicycle industry.

An advert from 1884.

Almost every cycle part was supplied to one manufacturer, or another,

from nuts, bolts, and washers, to tubes, frames, gears, and wheels. One

useful product that was sold to manufacturers was Pickard's lining

apparatus, which greatly simplified, and cheapened the lining process.

|

Read about

Pickard's

lining apparatus |

References:

“Wolverhampton Cycles and

Cycling” by Jim Boulton. Published in 1988 by Brian Publications.

“Stories of Tinplate Working and

Iron Brazier’s Trade, Bicycle and Galvanising Trades, and Enamelware

Manufacture in Wolverhampton and District” by W.H. Jones. Published in

1900 by Alexander and Shepherd Ltd, London.

|

Return to the

list

of manufacturers |

|

|