|

Anti-Burglar, Fire and Explosive

Devices

The never-ceasing war between the

locksmith and safe engineer on the one hand, and the burglar

and what the old-time journalist termed "the devouring

element" on the other, has been the means of producing

hundreds of devices for adding to the security of valuables,

and countering those dangers which are ever present owing to

the skill of the scientific thief, the ravages of fire, the

carelessness constantly displayed over the custody of keys,

and the neglect of ordinary precautions against fire which

often have such serious results. The latter day burglar is,

in many cases, not only a highly skilled specialist,

supplied with the finest of tools, but he carries out his

work with a coolness, skill and foresight that renders it

difficult to effectually frustrate his efforts. To go fully

into either the devices of the cracksman, or the methods

adopted by the locksmith and safe engineer to combat and

even anticipate them, would afford material for an extensive

volume.

As in the past the skeleton key and the

picklock, which rendered the warded lock vulnerable, caused

the introduction of the tumbler lock with its levers,

barrel, curtain and detector; so the drill, wedge, explosive

and blowpipe have brought into being the safe lock protected

by compound steel plates, the keyless combination lock, the

automatic time lock, the bent-cornered safe, the diagonal

bolt binding the safe door to its frame, compound armour

plate, and many other devices for the defeat of the skilled

burglar.

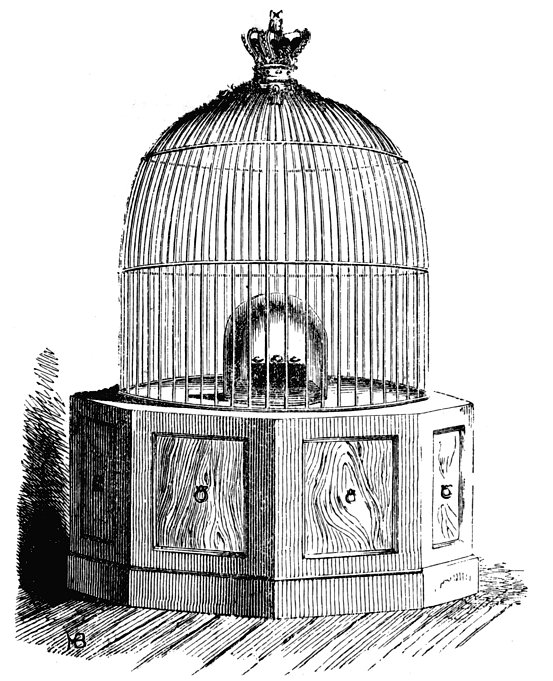

The latest patent taken out by Messrs.

Chubb protects a clever improvement of the principle

embodied in keyless combination locks used chiefly for the

doors of safes. Much is heard from time to time of

arrangements by which valuables displayed in a shop window

or showcase are lowered at night into a safe or armoured

recess, yet this method was used by Chubb's as early as

1839, and was applied by them to the receptacle made for the

safeguarding of the Koh-i-noor diamond at the Great

Exhibition in 1851. The cage-like structure, which is

illustrated from the original woodcut, was again

requisitioned in recent years for the display of some

notable diamonds of great value, the stones disappearing

into a vault at night.

In "Punch" of June I4th, 1851, appears

a fanciful dialogue between policemen guarding the

Koh-i-noor during the daytime, which ends: "It strikes

seven; the Koh-i-noor sets in its iron safe, and the

policemen depart."

|

|

The cage for the protection of the

Koh-i-noor diamond at the 1851 Exhibition, London. |

|

Freak Contrivances

Such excellent latter day contrivances

as the keyless combination safe lock and the electric alarm

had early prototypes. The present letter lock opening on a

certain word or number is the modern adaptation of a lock

existing in early times. In Beaumont and Fletcher's "The

Noble Gentleman" (1615) reference is made to "a strange lock

that opens with A.M.E.N.": while in some verses

by Carew addressed to May on his

"Comedy of the Heir," there is the following passage:

" . . . As doth a lock that goes with

letters; for, till everyone be known, the lock's as fast as

if you had found none."

In 1827 a locking device was introduced

for use on stagecoach boot doors and similar receptacles, by

which attempts at robbery were announced on an alarm bell

incorporated in the lock; the advertisement stating that

this "notice latch" had been tested on a coach from the

Bolt-in-Tun, Fleet Street, London, "with great satisfaction

to the proprietor." In 1871 this invention appeared again,

the bell-ringing being supplemented by the lighting of a

taper. About 1905 we again meet with it in the form of a

cash box, which on being lifted evinced its dissatisfaction

by the continuous ringing of a bell.

|

|

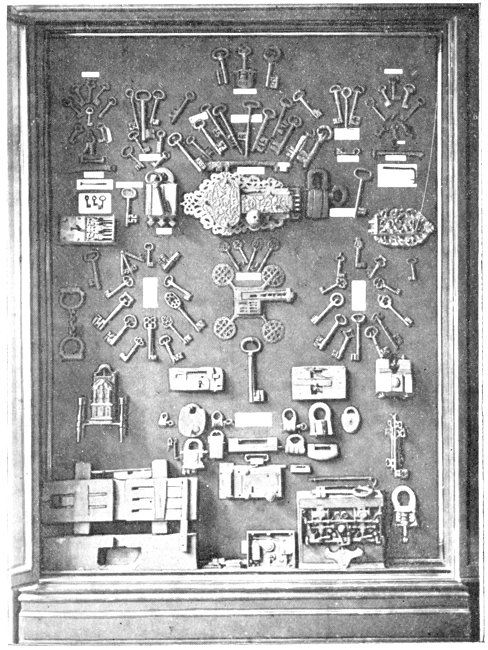

Antique locks and keys in the Chubb

collection. |

Age does not dim the lustre of these

devices, which are no doubt destined to be perennially

reinvented in various forms to the end of time. Many such

ideas emanate from well meaning folk who have not access to

records of inventions, and having little mechanical

experience are therefore ignorant of the fact that the

contrivances they devise are neither novel nor commercially

practicable.

This is not surprising, for many of the

principles embodied in modern locks and safes are of ancient

origin, and only adapted to modern requirements by the skill

of the experienced craftsman. The bolt work of many modern

safes is, in arrangement, very similar to that of the so

called Armada chests of the Tudor period; while certain

American locks with flat keys are kindred in principle to

ancient Egyptian locks contemporary with the Pyramids.

The

truth of the old saw, "Nothing new under the sun," has been

tardily admitted by many an enthusiastic inventor, who,

after laboriously working out what appears to him to be a

novel idea, has found himself anticipated by a craftsman of

the Middle Ages. |

|

It is almost impossible to say how many

so called patents have been taken out for locks and keys,

probably many thousands in Great Britain alone: and by far

the largest number are worthless from a practical point of

view.

Imitations and Infringements

A search at the Patent Office reveals

the fact that owing to the faulty Patent laws of this

country in bygone days, silly notions, impossible ideas and

duplicated inventions, even devices in vogue in the times of

the Pharaohs, were allowed to be patented at the expense of

the unfortunate inventor, alone benefiting the funds of the

Patent Office. Happily a better system now prevails, in that

a search is undertaken by the Patent Authorities, which may

prevent a man wasting his time and money in protecting an

idea which he fondly, but often wrongly, imagines has never

before occurred to anyone else.

A number of suggested

improvements are annually brought before the experts of

Chubb's Company by people who know little of the technical

side of lock and safe-making, and all that need be said

about these suggestions is that perhaps not one in a hundred

ever comes before the public as a practical and useful

article. The amateur inventor, however, is not easily

discouraged, and Chubb's have hid a wide experience of him,

his weak points and his views on the value of his

inventions.

In 1855 one gentleman offered a lock

whose many virtues appear to have impressed its originator

more than the maker to whom it was offered. He wrote to

Messrs. Chubb as follows: "As you doubtless desire to

possess a lock which possesses perfect security, I may

without apologising call your attention to a lock which I

have planned, which possesses perfect security. It is simple

in construction, strong, not easily deranged by dirt, and

great pressure may be applied to the bolt without injuring

the small works. It can be made to lock without the key; the

key may either move both the bolt and small works or the

small works only; the key has but one motion. Being blind I

have had ample leisure to examine and re-examine every part

of my lock, and I am certain that its security cannot be

surpassed. As I have several inventions which my humble

circumstances do not enable me to patent, I would willingly

sell to you the right to patent my lock for two thousand

pounds sterling. You will oblige me if you let me know at

your earliest leisure whether you will purchase it or not."

The fate of this masterpiece is not

placed on record, and the name of its ultimate purchase, if

any, is not known, but it seems reasonable to surmise that

the various virtues of this mechanical paragon were

discounted by some drawback which failed to appeal to the

instincts of the Chubb experts, and that "the Noes had it."

|

|

Chubb's firm, like other old ones, has

ever been jealous of attempts to make wrongful use of their

name or trademarks. In 1849 we find them petitioning

Parliament. The method then necessary to extend to their

manufactures the protection afforded to cutlery, and citing

the case of a Birmingham locksmith, who, having made use of

their name on his locks and being mulcted in damages and

costs, left the City without going through the formality of

paying either.

That manufacturers had to take stern

measures to protect themselves is indicated by an

advertisement dated February 4th, 1845, in which a defendant

named Thomas Davis writing from Warwick Gaol, intimates that

he is at present there resident at the suit of Messrs.

Chubb, whose name he had placed on locks not of their

manufacture, but who in consideration of the "distressed

state of my wife and family, by reason of my imprisonment,

consented to my discharge.

I do hereby declare that I deeply

regret having ever put their names on my locks, or having

passed off locks of my make for articles of their

manufacture, and I solemnly promise that I will never again,

under any circumstances, commit the same offence." This

declaration is significantly witnessed by "Thomas Maycock,

Turnkey." Human nature in 1845 was much the same as in this

year of grace. |

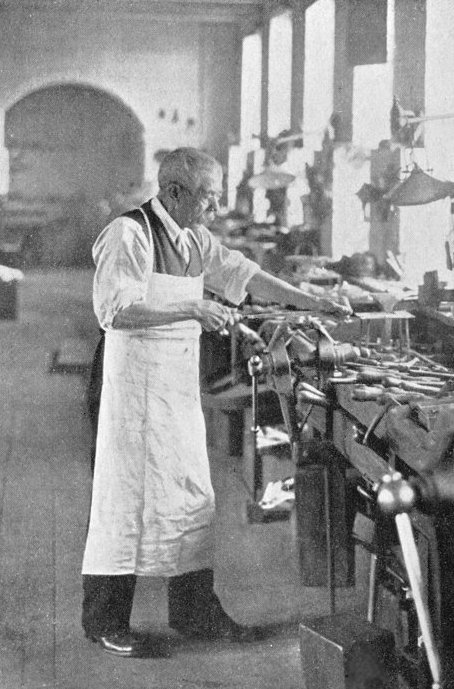

Harry Inscoe. Who completed 60 years

of service on October 9th, 1918 and is still lock making. |

|

Thomas Davis's prototype of today still

fails to indicate how solicitous he is for the welfare of

his unfortunate wife and family until his misdemeanours have

placed his own person in danger.

The Chubb archives record several

attempts to make improper use of their name in connection

with goods not of their manufacture; but protective

legislation has enabled the Courts to emphatically confirm

Chubb's absolute right to the sole use of their name in

connection with the production of locks and safes.

Perhaps one of the most recent and

interesting latter day decisions in connection with

trademarks was that by which the blanket makers of the

Oxfordshire town of Witney were granted definite legal

confirmation of their ancient right to the exclusive use of

the name of their town as applied to their well known Witney

blankets. Apart from its importance as a trade decision, the

Witney case seems specially pertinent to our present

subject, as the ancient blanket making family of Early,

prominent joint plaintiffs in that action, is closely allied

by family ties with the House of Chubb. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Chapter 1 |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Chapter 3 |

|