|

From Coffer to Safe Deposit

From the wooden chest or coffer dug out

of a solid tree trunk or constructed of massive timbers,

which formed the early receptacle for valuables to the

latest safe deposit and treasury is a far cry. Those who

wish to study the evolution of the ancient wooden coffer and

its manifold forms should consult Mr. Fred Roe's intensely

interesting work "Early Coffers and Cupboards."

Our present

concern, however, is with metal receptacles. Perhaps the

form that approximated most closely to the modern safe, and

which has survived in considerable numbers, is the medieval

treasure chest, a large iron oblong box constructed of heavy

bands of metal and leaving a ponderous lock in the lid,

throwing many bolts under a flange round the mouth of the

chest. The interlaced bands of iron of which these chests

were constructed remind us that in those days the production

of iron steel sheets by rolling was, of course, unknown;

even the larger surfaces of armour, etc., were produced by

hammering out metal to the required thickness.

|

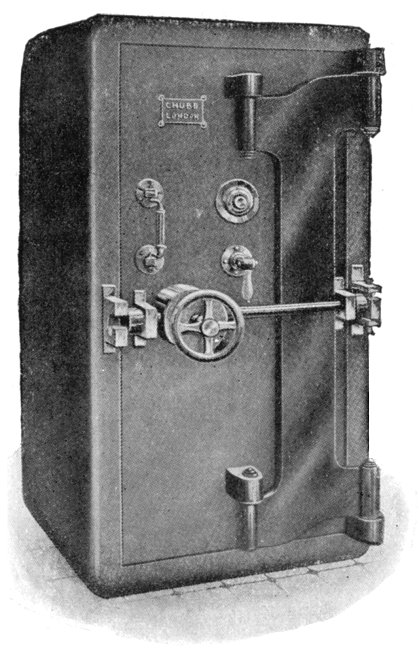

A modern Chubb patent anti-blowpipe safe,

fitted with a crane hinge and keyless lock. |

The keyholes of these chests were

ingeniously masked, and in certain cases the lock in the lid

was either supplemented or replaced by heavy hasps secured

by padlocks. Such chests are frequently found in muniment

rooms, in the halls of trade guilds and in museums; they are

of considerable strength, the complicated and finely

constructed bolt work and warded locks offering sturdy

resistance to the old time marauder. Indeed, in cases where

their large warded keys have been lost, the opening of such

chests has often been a lengthy process even for the latter

day locksmith. Most of these chests appear to be of foreign

construction, the covering plates of the lock work being in

many cases finely fretted and chased, while in other cases

decorative painting adds to their interest.

These and the later forms of iron chest

or safe, however massive, afforded little or no protection

against fire, and the necessity for receptacles giving some

measure of fire resistance resulted in the introduction of

various forms of proofed safes, the walls of which were

packed with certain substances designed to give off vapour

on being subjected to high temperature and assist in the

preservation of the contents of the safe.

The constructional

details of many of these early safes were open to criticism,

especially as regards the arrangement of the bolt work, and

the method of attaching the outer plates to the framework.

|

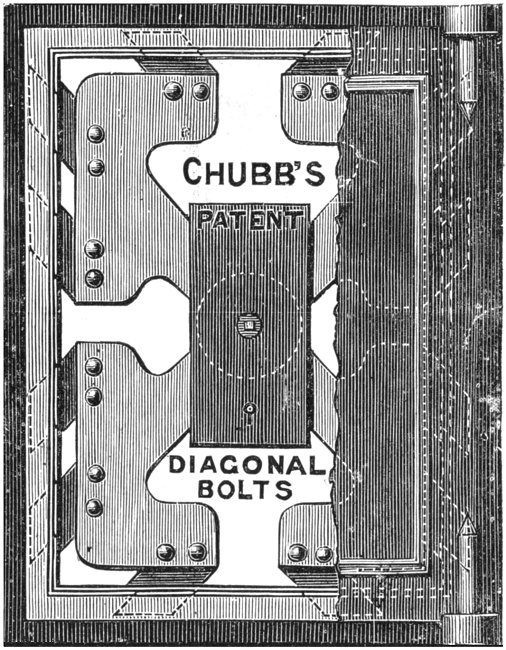

| Perhaps one of the most outstanding

improvements introduced by Chubb's was the diagonal bolt

system, which being first applied by them to locks about

1847, was later on improved and successfully applied to

safes and strong room doors, proving to be one of the most

effective arrangements ever devised for binding a safe or

strong room door to its body or frame.

The illustration below shows the manner in which the bolts, instead of

shooting straight from the door into their sockets or

flange, emerge diagonally and enter angular apertures

provided in the body of the safe or frame of door, knitting

the frame and door together with especial tenacity. Another

improvement was the substitution of round bent corners for

the rectangular safe corners formerly constructed, thus

preventing the insertion of wedges into the angle joints and

the wrenching off of the back of the safe, a favourite

method of the burglar in dealing with the commoner types of

safes, and sometimes attempted in the case of those of

leading makers |

| Some years ago it became the practice

to protect the locks of better class safes and strong room

doors by hard steel plates as a protection from drilling.

Later on compound drill resisting armour plate consisting of

alternate layers of steel and other metals of varying

hardness was used in the construction of the bodies of both

safes and rooms, special combinations of metal being devised

to counteract the use of the blowpipe, which had in many

instances been successfully employed in penetrating ordinary

plates by melting holes in them.

Among other recent innovations in safe

and door construction by Chubb's is the Stelocrete system,

by which use is made of a special form of ferro concrete,

which has proved singularly effective in the case of party

wall and other doors designed to prevent fire extending from

one building to another, the severe tests to which such

doors have been subjected having given most satisfactory

results. The system has also been applied with success to

the construction of safes. |

The diagonal bolt principle. |

|

Space prevents extended details of

these protective materials and devices, but brief reference

may be made to some of Chubb's more important strong room

work. A quarter of a century ago a sensation was created by

the production of a steel strong room of such dimensions

that its completion was celebrated by an extensive luncheon

party being accommodated in its capacious interior.

Rooms of far greater

dimensions are now regularly produced, and, with future

reduction of the Government's war requirements, will, no

doubt, increasingly occupy the Chubb factories. Some idea of

their strength may be gained from the fact that certain

recently constructed treasury doors alone have weighed, with

frame, nearly ten tons, yet so accurately are they poised on

their massive crane hinges that they can be moved by one

hand. |

|

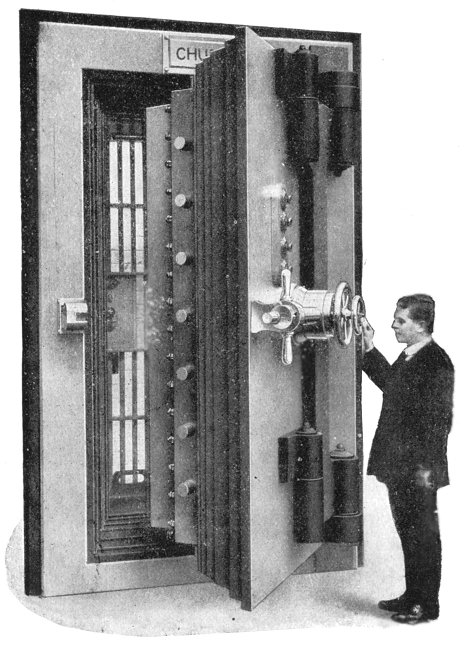

Crane Hinge, Armour-Plated Strong Room

Door, weighing 6 tons. |

In such doors, keyholes, which might

afford an opportunity for the insertion of explosives, are

absent, the bolt work being controlled by keyless

combination locks and time locks fitted behind the massive

plates of the door and only allowing of the door being

opened after a certain prearranged hour, and then only on

the simultaneous attendance of three officials. All these

arrangements are designed to baffle the modern cracksman,

who presses into his criminal service a number of weapons

unknown to the burglar of a century ago.

Armed with modern

explosives and with the oxy-acetylene blowpipe, few indeed

are the safes of a past era that would provide any defence

against these tremendously potent modes of attack.

Chubb's

present day work, therefore, is directed towards the

construction of security work which can successfully defy

both nitro glycerine and the white heat temperatures of the

modern blowpipe and electric burning. |

|

Chubb's "Triple Treasury Construction"

with its indispensable adjunct, the crane hinge door,

constitutes the last word in security construction, and has

been proved to resist effectively even bombardment with

naval gun shells. Speaking broadly, this construction

consists of two steel strong rooms, one inside the other,

both built of Chubb's interlocking plates, the space between

being filled up with about a foot thickness of specially

armed concrete.

The many patented improvements designed

by Chubb's during the past 100 years indicate how they have

followed and countered the various wiles of the burglar by

protective methods born of their long experience. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Chapter 2 |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Chapter 4 |

|