|

JEREMIAH SMITH AND SON LTD, 9 NEWBRIDGE STREET, WOLVERHAMPTON

The Memories of A.J.V. Whitehouse

Tony Whitehouse provided the following memories of this

firm in 1999. All the photos were taken in 2002. Thanks to Neil

Turner for cheerfully allowing entry to take photographs.

My mother was Mabel Helen Whitehouse, nee

Jones. Her father was Jeremiah William Jones who was the Working Director

and Manager of Jeremiah Smith & Sons circa 1920.

He lived at 9 Newbridge Street until the mid 1930s, when he

moved to a new semi detached house at Pendeford Lane, Wolverhampton. The

other directors of Jeremiah Smith & Sons Limited were Fred and Ernie Smith;

but I have no recollection of where they lived or their background.

|

|

Numbers 9 & 10 Newbridge

Street. A pair of late 19th century houses with an access way

between them which once lead to the lockworks. |

|

I was born on 31 January 1925 at 87 Newbridge Street,

which is almost opposite to number 9.

Number 87 was at that time owned by J. W. Jones. We

certainly paid rent to him right up to his death during World War II, when

it was willed to my mother.

|

| From an early age, once I had become

mobile, probably from 4 years onwards, I was a frequent visitor to the

lockworks and often played in the comparative safety of the yard.

Number nine itself was the home of J. W. Jones, thought eventually it

came to serve as an office building.

In the yard behind the house there were four distinct

buildings. All the buildings were of typical early/mid Victorian

industry style with arched metal framed windows.

The manufacturing

interiors were brick or earth ground floors, solid wooden stairs and

floors at first floor. There were no ceilings. All the beams and roof

structure were exposed. |

87 Newbridge Street

|

|

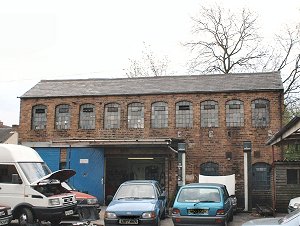

The works seen from

Newbridge Street. The gate piers to the right gave access to

the works but were not generally used.

Mr. Hill's house would have

been to the right of them but is has now been replaced by modern houses. |

The lockworks of Jeremiah Smith & Sons Ltd., circa 1930.

1: the warehouse, with the office at the

Newbridge Street end.

2: the main workshop,

3A: the casting shop

3B: the machine shop

3C: derelict workshop, originally

with internal stairs to the upper floor. Disused before 1925.

Demolished by 1999.

Behind No.10 is its garden. Behind that,

next to the main workshop, was the garden area for No.9. The area

between the warehouse and the derelict workshop was rough, disused

garden ground. The house on the right was that of Mr. Hill, the

Secretary. |

|

|

Detail of buildings

2, 3A and 3B above. 1: coke and

sand store

2: casting shop sand tray; there was a

plinth on the other two sides.

3: machine shop bellows forge.

4: line shafts, with drive from -

5: gas engine

6: The main workshop, of two storeys.

There were work benches round all sides of both floors, with stairs in

the centre.

|

| A particular feature, which I well remember, was the

gas engine, which was a single cylinder and crank machine driven from the

town gas supply. It had a large flywheel about 6/7 ft in diameter which had

to be swung, rather like an aircraft propeller, to start the engine. There

was a pilot jet to fire the gas, which was admitted and regulated by a set

of rotating governors half linked to the output drive. When running, the

intermittent thump thump of the engine was a workday feature of the

neighbourhood. But I cannot recall anyone complaining about it. |

| On the side of the crank support frame

opposite to the flywheel was the main drive pulley for the belt driven

machinery. This extended through the machine shop wall and through to

the main workshop where there were line shafts and belts everywhere.

I was never encouraged to get too near because of the particles flying

from the grinders etc. and the belts coming off.

There was also a typical bellows coke forge at one end

of the machine shop. |

The main workshop |

| Even with the machinery, files were very much a work

tool and I remember small sacks of files going out for re-cutting and into

the works as new. Where they went or came from I never knew. |

The main workshop seen from the St. Jude's

School end. |

The real place of interest was always the

casting shop, where there was a hand bellows operated coke furnace in

the corner. Brass would come in as either small ingots or scrap and be

dropped into what looked like a grey graphite crucible pot nestled into

the hot coke.

When the moulds had been prepared and all was ready,

the caster would lift out the pot of molten brass with hand tongs,

scrape off floating dross and then pour the liquid metal into three

separate holes in each mould block until they were just full, then move

on. Usually there would be four, perhaps five, mould frames.

When pouring was going on the small casting shop

filled with grey sulphurous fumes, with bits floating in the air like

snowflakes. |

| The next process was to allow the brass to set and then

to break open the mould blocks to reveal the still hot and smoking raw

castings, looking rough and blackened, attached to the main mould feeds. The

useful castings, usually the lock casings, were then broken off, quenched

and sent as a batch to the workshop. |

| The sand from the casting would be fine

riddled and the lumps discarded. New red sand was added to make up as

needed. The caster would then fill half of the mould block with damp

sand, level off and carefully insert the mould patterns into the sand. A

few deft taps and the patterns were removed. Filling channels were

pressed in, then the prepared mould surface was given a light dusting of

pounded up soft brick dust from a shaker bag. The mould halves were

brought together and the process repeated.

The previous mould cores were of course recycled into

the pot for re-melting.

I have no idea of the method employed to determine the

correct copper/zinc alloy proportions (should it have been deemed

necessary). |

The upper floor of the main

workshop

showing the open roof.

|

| In the machine shop and workshop there followed all

the drilling, filing and finishing processes which resulted in the finished

product. |

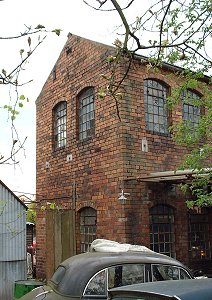

The casting shop on the left and the machine

shop on the right. The gas engine shed has been demolished. |

The lock levers were made from strip

brass, pressed out to shape using hand fly presses. The lever

combinations could be altered by using different fly press tools.

I

cannot remember seeing any of the final processes which matched the

shaped keys to the levers.

From the workshop the finished locks went

into the warehouse where they were impressed with the maker's name etc

by hand fly press, lacquered, dried and then wrapped in tissue and boxed

in cartons ready for dispatch. |

| The warehouse walls were covered in a multitude of open

fronted small wood box storage compartments to act as stores for all the

various bit and pieces for manufacture and as storage for some finished

locks. |

| The office area comprised of a Dickensian

long desk with a couple of tall stools and the usual record file racks.

I cannot remember any closed filing cabinets but I think there was a

small safe. During the mid 1930s the common line shaft and belt drive

machinery was replaced by individual electric motors.

Transport of materials to and from the lockworks in the 1920/1930s

was almost entirely by horse drawn, iron wheeled wagons (mostly LMS).

One dare by us lads was to creep under the horse whilst it was waiting

for the delivery driver. The horses never seemed to mind.

During this time there would have been about 30 people employed at

the works but this number gradually reduced until the works closed.

|

The chimney to the machine shop bellows

forge is still in place.

|

|

In my teenage years and later, although I continued to

live at 87 Newbridge Street until 1948 (3 1/2 years war service in Royal

Navy included), my interest in the lockworks waned, particularly after my

grandfather vacated 9 Newbridge Street. In the mid 1950s I was once asked to

represent my mother (who had shares left to her) at a shareholders meeting,

one item of which was to consider appointment of Mr Hill, the secretary who

had served Jeremiah Smith in an executive capacity for many years, to

position of Director. This was voted out.

In keeping with the tradition of the time my grandfather,

Jeremiah Smith, was also an active Methodist supporter and regularly

attended Cranmer Methodist Church, where I also attended and was married in

July 1948.

In May of 1999, out of curiosity, I visited the lockworks

site, part of which is now occupied by a car repair business. The present

occupants were very helpful. Their car repair business is on the area of the

old lockworks machine shop and ground floor of the lock workshop. The

buildings are still existing pretty much as I remember them but now seem

remarkably small compared with how I recollected them. I did not enquire

whether the old warehouse or Number 9 were still accessible.

One possibility that has occurred to me is that the works of

Jeremiah Smith & Sons probably represent the western limits of lockmaking in

the Wolverhampton/Willenhall area.

|

|

Return to the

list of makers |

|