| Bad Weather and

Epidemics During the first three months of

1870 there was a severe frost and a lot of snow, which

meant that work outdoors was almost impossible. Many

people were out of work due to the severe weather and so

the council set up a fund to raise money for the

distribution of bread and oatmeal to the poorer members

of society.

There was a great storm on the

night of Sunday the 15th October, 1877, during which a

large number of trees and chimneys were blown down.

The Smallpox Epidemic

A smallpox epidemic broke out in

Wolverhampton in the autumn of 1871. Many people

suffered from the disease, particularly the poorer

people living in slum properties. There were many

fatalities including the sister of Mr. Edwards, a

butcher with a shop on Penn Road. The disease greatly

alarmed the local population, to such an extent that Mr.

Edwards’ sister was buried within 48 hours of her death.

Vaccinations were offered free of charge and many

surgeons were employed as public vaccinators. Posters

were put-up, all across the town, advising people to get

vaccinated.

Dr. Manby was appointed Medical

Officer of Health and the General Hospital soon filled

with smallpox patients. The old, empty police station in

Garrick Street (later the Free Library) became a

temporary hospital. To prevent the spread of the

disease, smallpox inspectors were appointed to visit

places were many cases occurred and to ensure that

anyone affected would be transferred to the temporary

hospital. They also disinfected houses and courtyards

and had them cleaned and whitewashed.

By December, 109 people had died.

57 of them had not been vaccinated and 39 had only been

vaccinated once. The vaccinations were successful and

the disease eventually disappeared in July, 1872. During

the epidemic, 483 people died from the disease, which

had cost the Borough over £2,000.

During the epidemic, the Local

Government Board’s Medical Officer, Dr. Ballard, was

sent to Wolverhampton to investigate the cause of the

epidemic. He reported that the sanitary conditions in

the town were most unsatisfactory. Water from wells used

for drinking and cooking was often contaminated with

sewage and dangerous to life. The town was badly drained

with inadequate sewers, which should receive the

immediate attention of the Town Council.

Dr. Manby retired from his post as

Medical Officer of Health and was replaced by Dr. Love,

who took control of a staff of medical inspectors. The

Council also appointed Mr. E. W. T. Jones as Borough

Analyst, whose job it was to test drinking water and

check the quality of food.

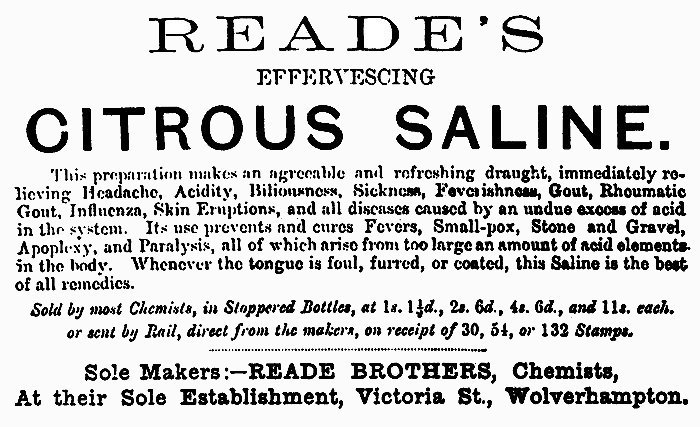

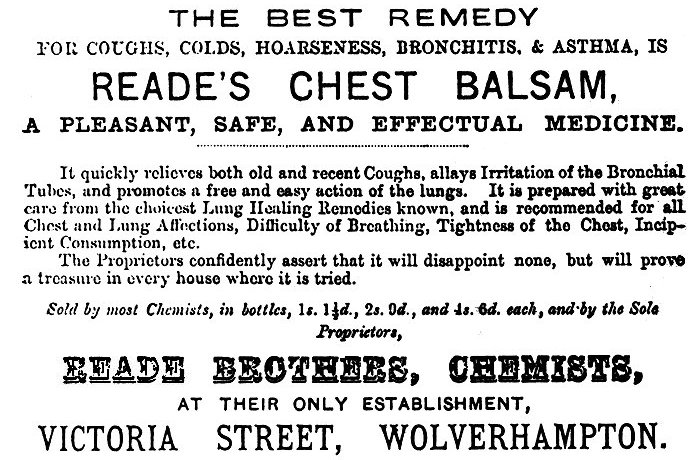

An advert from 1877.

Another Epidemic

In 1873 there was an outbreak of

typhoid, which first appeared in Darlington Street. The

first victims included the wife and daughter of the Rev.

T. G. Horton of Queen Street Congregational Church, the

two daughters of the Rev. G. Everard of St. Mark’s

Church, and the wife of Mr. Smallwood, a draper. They

all died within a few days and the disease rapidly

spread to other parts of the town. Up to 38 people in a

1,000 died. Dr. Love, the Medical Officer, reported that

the fever had been caused by water polluted with sewage.

The outbreak began when a milkman who supplied houses in

Darlington Street had been diluting his milk with a

little water from the Black Brook, which was an open

sewer. 69 of his customers, from Snow Hill to the bottom

of Darlington Street had typhoid, thirteen of them died

from the disease.

At the next council meeting it was

decided that any well containing water that was found to

be polluted, should immediately be closed. The fever

gradually disappeared and Dr. Ballard, the Special

Commissioner from London, who visited the town in

December 1873, reported that open piles of refuse and

animal waste and wet ash pits should be done away with.

He also reported that the narrow, crooked streets, the

poorly ventilated courtyards, and the old dilapidated

slum dwellings were a constant source of danger.

Although Dr. Ballard’s report was considered by the

Sanitary Committee, nothing was done for several years.

An advert from 1877. |