| |

|

|

Read about Coal and

Ironstone Mining |

|

| |

|

|

The

following local manufacturers are listed in

William White's 1851 ‘History, Gazetteer and

Directory of Staffordshire’:

James Bailey,

Willingsworth

William Banks.

Ettingshall

William Barrow, Quarry

Hall

Bennett & Pemberton,

Deepfield

Colbourn & Groucutt,

Bankfield

Josiah Cresswell,

Woodsetton

Haines Brothers, Willingsworth

Round Daniel George,

Daisy bank

Samuel Smith. Rookery

Hall

Joseph and Thomas

Turley, Coseley Furnaces

Henry Bickerston

Whitehouse, Wallbrook

Philip Williams and

Sons, Wednesbury Oak

Ironfounders:

David Green, Coseley

Foundry

James Johnson, Broad

Lane

Edward Sheldon |

|

|

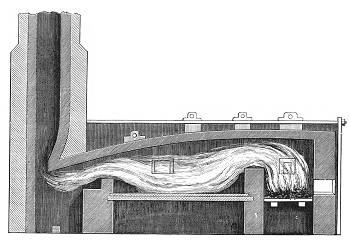

A section

through a puddling furnace. |

The most common method

of producing wrought iron from pig iron in

the 19th century was puddling, invented by

Henry Cort in 1784. Pig iron or scrap cast

iron was melted in a puddling furnace and

stirred with a long pole, which reduced the

carbon content by bringing it into contact

with air, in which it burned. The puddling

furnace heated the iron by reflecting the

exhaust gases from the fire down onto it. In the drawing

opposite, the iron would be placed in the

central section. Because it was not in

contact with the fire, cheaper, poor quality

fuel could be used. After puddling, the iron

was hammered and rolled to remove the slag. |

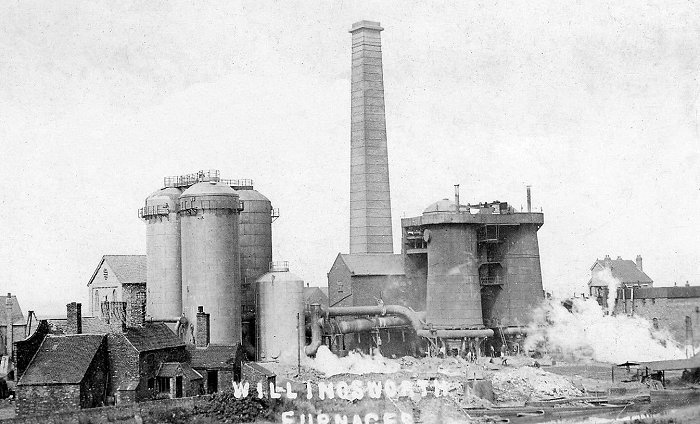

The large furnaces at

Willingsworth, operated by the Willingsworth

Iron Company Limited, were founded in 1827 by the

Yates Family. The firm was later run by Sir

Horace St. Paul, and then the Willingsworth

Iron Company. The principal partner was

David Kenrick, of Wolverhampton. In 1902 the

firm was incorporated into the newly formed

Metropolitan Amalgamated Railway Carriage

and Wagon Company, which in 1912 became the

Metropolitan Carriage, Wagon and Finance

Company Limited. In 1939, the ironworks was

absorbed into the Patent Shaft and Axletree

Company of Wednesbury, then liquidated.

Willingsworth

Ironworks. From an old postcard.

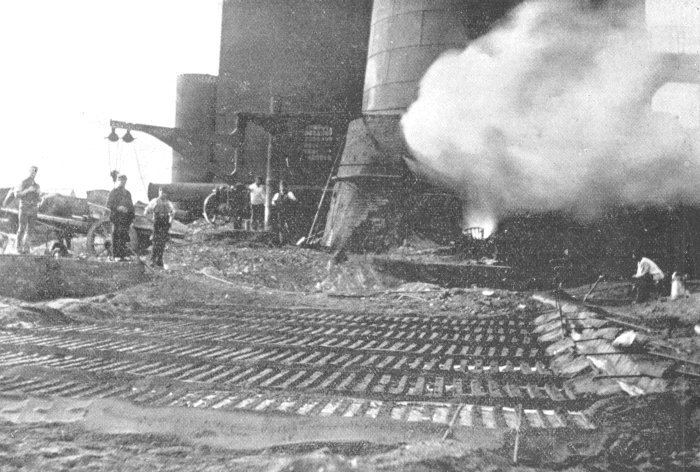

Tapping

one of the furnaces at

Willingsworth Ironworks. The

molten iron was run into

channels cut into sand to

produce iron ingots. This was

known as a pig bed. The iron was

called pig iron because during

casting, the ingots were likened

to a piglet suckling milk from a

sow. |

Next to the ironworks

were large slag heaps and spoil heaps from

the adjoining Willingsworth Colliery. The

slag heap was known as ‘Elephant Rock’

because the end that faced the nearby G.W.R.

mainline was shaped a little like an

elephant’s head. The other large spoil heap

was known as ‘Tiger Rock’ because of the

different colours in the layers that it was

made of. The heaps were destroyed by

blasting in the 1980s and a housing estate

was built on the site.

The view

from the top of 'Elephant Rock',

looking across the Great Western

Railway line, where the Midland

Metro now runs, towards Chance

and Hunt's acid works. |

An aerial view of

Chance and Hunt's acid works with 'Elephant

Rock' to the right.

Tiger Rock.

Another early industry

was nail making. At the Coppice, many

nailers' cottages were built, along with a

nail warehouse. The nail makers relied on

the ironmonger, the middle-man who supplied

them with bundles of iron rods, weighing

some fifty or sixty pounds each. He then

purchased the finished nails from them,

often for tokens instead of cash. The

nailers mainly worked in outbuildings next

to their cottages and were self-employed,

usually working long hours for little

reward. The whole family, husband, wife and

children could be producing nails. They were

totally dependant upon the ironmaster who

gave them work when it suited him, and could

also delay payment for finished nails until

he saw fit.

The nailers were

amongst the poorer members of society, often

with an irregular income, working extremely

hard for many hours at a time, before being

idle until more work came along. The

industry rapidly declined in the nineteenth

century when machine-made nails began to be

produced in the Black Country, from about

1830.

Steel pen nibs were

another early product being produced both in

Coseley and in Sedgley. Each town lays claim

to have been the first in England to

manufacture pen nibs. Thomas Sheldon, a

forerunner of the Sheldons who later owned

the Cannon Iron Foundries at Coseley, was

making them for Mr. Daniel Fellows of

Sedgley, as early as 1806. They were sold by Beilby and Knott, a Birmingham firm of

stationers, until about 1828.

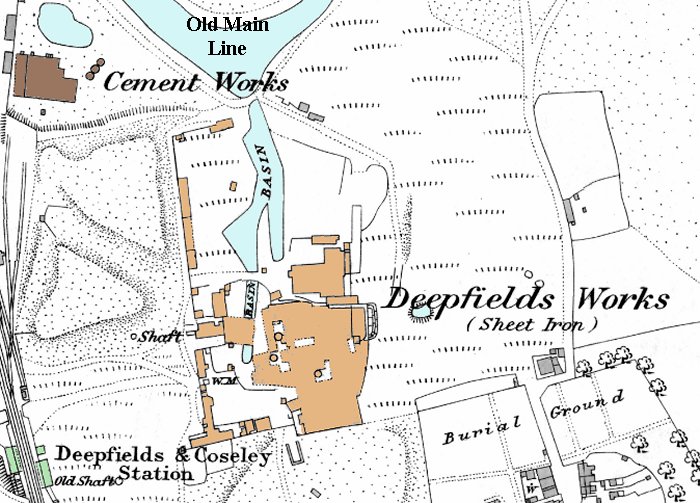

Local industries

flourished because of improved transport

facilities. The local canals made a great

difference, as did better roads, thanks to

the turnpike trusts. The local railways

which came along in the 1850s allowed goods

to be rapidly transported over much greater

distances, all of which led to the opening

of many factories and workshops. Deepfields

was ideally situated to take advantage of

the new transport facilities. The canal, the

railway, and turnpiked roads were close at

hand, which led to the opening of furnaces,

iron foundries, brick yards and collieries

in the near vicinity. One such firm, Edward

Sheldon and Company, would later become

Cannon Iron Foundries Limited, and Priorfield

Furnaces, built for H. B. Whitehouse, which would

become one of the largest of their kind in

this part of the country. Henry Bickerton

Whitehouse was a well-known local ironmaster

who was later joined in the business by his

son, Benjamin. Samuel Griffiths, in his

'Guide to the Iron Trade of Great Britain'

published in 1873, had this to say about the

firm:

|

At Deepfields they

have facilities for

making sheets and

boiler plates equal

to any other works

in the

neighbourhood. The

quality of the

plates here is good,

the sheets are well

annealed, and the

shears being of the

most modern type.

Plates and sheets

are turned out at

Deepfields, not only

of good quality, but

in a clean and

handsome condition.

|

|

Wednesbury Oak

Ironworks to the north of Wednesbury Oak

Road were built in 1820 and operated for 100

years. The firm was called Philip Williams &

Sons, whose 'Mitre Brand' of best quality

iron had a high reputation throughout the

world.

In 1833 there were at

least 20 screw makers and screw forgers in

Upper Ettingshall and wood screw makers,

including Enoch Allen, Simeon Allen, William

Saunders and Bennett Waterhouse. Fire iron

manufacturers established themselves in

Coseley and Woodsetton including the

Wolverston brothers and Stephen Hipkins of

Princes End.

A firm of whitesmiths was founded in

Woodsetton and locks were made locally by

William Bowyer, William Lowe, and John

Newton. There were at least five

wheelwrights: T. R. Bennett, George Church,

Joseph Cooper, John Peacock, and Edward

Weaver.

An advert from 1965.

An advert from 1965.

The local clay deposits

led to the formation of brick and tile

making works. Brick makers in the 1850s

included James Bates, Edward Cartwright,

George Church, Job Elwell, and Benjamin

Gibbons. Some brick makers, including Thomas

Hinton, Benjamin Johnson, John Mellard, and

William Waterfield produced

fire-bricks. Many of the bricks and tiles

were used to line some of the Staffordshire canals.

Much of the locally

quarried limestone was used to produce lime

fertiliser. Lime burners included Joseph

Baker, Thomas Baker, John Ellis, James

Johnson, and Wade Smith. Quarry owners

included John Parker and Samuel Saunders.

In the 1850s there were

still many farms. Farmers included William

Ashcroft, Thomas Barrs, John and Joseph

Beddard, Samuel Brown, John and Benjamin

Caswell, William Clarke, James Deeley,

Samuel Finch, Abel and William Fletcher,

John Gibbons, John Hodson, John Jukes,

Thomas King, Prudence Law, Benjamin Marsh,

William Perry, William Reade, Thomas Rhodes,

John Ritson, Henry Smith, Isaac Thompson,

and Mrs. Titley.

There must have been a

great contrast between the farms and the

heavily industrialised areas, which were

like almost any other Black Country town.

There were many spoil heaps, some emitting

smoke from hot furnace droppings, which

competed with an overall pall of smoke from

the many chimneys and furnaces. Much like

the saying about the Black Country; ‘Black

by day and red by night’.

This is what the Vicar

of Coseley, the Rev. William Ford Vance, had

to say on his arrival here in 1850:

|

Black, in truth, it

now is, alike in its appearance, and in the

character of a large section of its

inhabitants. Black in its rugged and dreary

aspect, diversified with heaps of molten ore

and smouldering dross, and with those dark

piles of brickwork ever emitting smoke or

flame - black in regard to the minerals

extracted from its caverns - black from the

dense clouds of sooty vapour which blight

its vegetation, and shroud its sky with a

funereal pall - black with dilapidated and ruined habitations,

strewn in all directions, like the ravages

of a general earthquake or volcano eruption,

but many of which, melancholy to reflect,

are yet tenanted by whole families of human

beings - black as to the unwashed and

dejected faces of those miserable drudges,

who seem to have toiled all their lives in

dirt and darkness.

He also stated that in

Coseley alone, there were over 800 widows

and orphans; their state due solely to fatal

accidents in the mines or the factories.

|

|

Many of the locals were

paid, or partly paid with tokens, which had

to be exchanged for goods, often overpriced,

in the so called Tommy shops, as part of the

notorious truck system, which exploited much

of the workforce. The invidious practice was

not outlawed until Parliament passed the

Truck Act 1831, which made the practice

illegal in many trades, followed by the

Truck Act 1887, which outlawed it

completely.

|