|

Canals

Coseley’s rich mineral deposits

were being exploited by the beginning of the 17th

century when licences were granted for the mining of

‘sea cole and ironstone’. At that time, roads were

only dirt tracks, which were totally unsuitable for

heavily laden vehicles and often impassable after

periods of heavy rain. Any minerals mined, must have

been used locally, as it was impractical to

transport them over any great distance.

By the 18th century, there was

a great demand for coal to supply Birmingham's many

industries. Coal was in abundance in the Black

Country and so plans were made for the building of a

canal to transport it there.

The first canal in the area was

the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal,

connecting the River Severn at Stourport to the

Trent and Mersey Canal at Great Haywood. Building

work on the canal, surveyed by James Brindley, began

at Stourport in 1768. The canal was navigable as far

as Compton in November 1770, and opened in its

entirety in 1772.

In January 1767, a public

meeting was held in Birmingham to discuss the

building of a canal from Birmingham to the

Shropshire and Worcestershire Canal, via

Wolverhampton and the Black Country's many coal

mines. By August, sufficient capital had been raised

to fund the project, and a Bill allowing

construction was passed in Parliament in February

1768. The Birmingham Canal Navigations was

incorporated on 2nd March, with James Brindley as

engineer.

In 1768, work quickly got

underway. The Wednesbury line was completed in 1769,

allowing coal to be transported to Birmingham from

collieries at Hill Top. The first boat load of coal

bound for Birmingham left on the 6th November, 1769.

By 1770 the canal reached

Tipton, then followed an extremely circuitous route,

along the natural contours, to avoid the high ground

in the Coseley area. James Brindley was a great

advocate of contoured canals, to avoid the building

of locks wherever possible, the excavation of

cuttings and the digging of tunnels. The canal

skirted around Bloomfield, towards Wednesbury,

before doubling back on itself to follow a loop

through Bradley to Deepfields.

Wolverhampton was reached in

August 1771, but the final downhill section to

Aldersley Junction took another year to complete,

because it required the building of 21 locks.

Initially 20 locks were built, but because of the

large drop at the bottom lock, an extra lock was

added. The Canal opened on 21st September, 1772,

just 8 days before Brindley's death. |

|

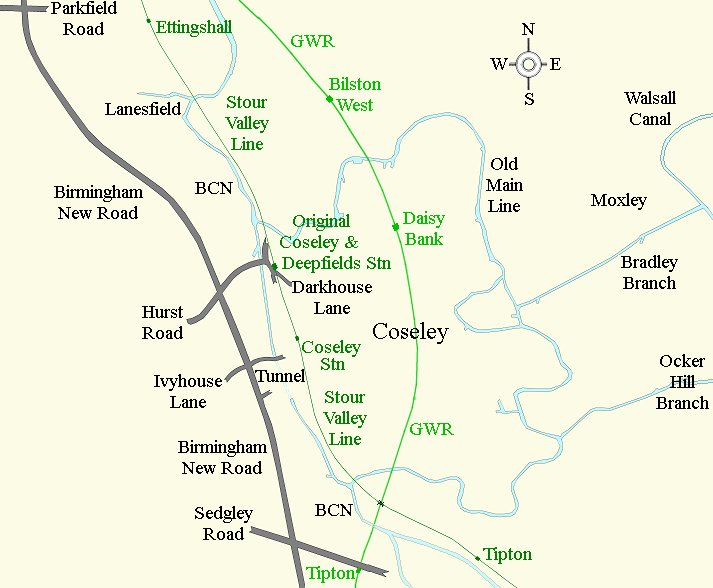

Canals, railways and

Birmingham New Road. |

|

The finished canal was over

22½ miles long and covered just over 12½ miles

as the crow flies. Other branches soon followed,

including the Ocker Hill Branch, built in 1774,

which was included in the original Act.

The Walsall Canal was built

under the terms of an Act passed by Parliament

on 24th June, 1783, which included the Toll End

Branch. It was surveyed and designed by John

Smeaton, the first self-proclaimed civil

engineer. The canal had eight locks at Rider's

Green, and reached Wednesbury in 1786. It

finally opened to Walsall in 1799.

In 1796, work began on the

Bradley Branch, which joined the Walsall Canal

to the old main line, via a flight of nine

locks. It also bypassed the Bradley Loop and

opened in its entirety in 1849.

The original Birmingham

Canal, known as the old main line, had one draw

back, which was the extra ten miles or so that

had to be covered by the circuitous route around

the high ground in Coseley. In 1824, Thomas

Telford was engaged to survey a canal to bypass

much of the route through Bradley, and go

directly through Coseley.

An Act for the building of

the canal was passed in June 1835, and work soon

got underway. Telford decided to tunnel under

part of Coseley in a 360 yard, brick-lined

tunnel, with a deep cutting at either end. The

tunnel was built with a brick-surfaced tow path

on either side of the canal, so that boats could

pass one another in the tunnel, without waiting

to queue. The section from Deepfields to

Bloomfield, including the tunnel, opened on 6th

November, 1837. The new mainline was completed

in April 1838. It is seven miles shorter than

the original route, and very straight. |

|

The northern end of

Coseley Tunnel in 2014. |

|

Another view of the northern end of Coseley Tunnel in 2014. |

|

Inside the Coseley Tunnel. |

|

Looking towards the

southern entrance. |

|

The southern entrance

to the tunnel. |

|

The cutting on the

southern side of the tunnel. |

|

The new canals were a great

success. For the first time, goods of all kinds could be

cheaply and reliably transported over long distances.

The large quantities of coal, limestone, raw materials,

and finished goods that were transported on the canals

at the time, made the canal companies very wealthy,

greatly benefiting their shareholders. Large factories

sprung-up alongside the canal, and the population of

many local towns rapidly grew thanks to the employment

on offer. The cost of some of the items for sale in the

shops fell, due to large scale manufacturing and ease of

transport, and a greater variety of goods could be found

in the shops.

The canal network was connected to

sea ports, so that manufacturers could easily export

their products, and many imported goods were readily

available for the first time. The falling cost of coal

encouraged new industries to develop, and reduced

people’s heating bills.

One of the most successful carriers

and boat builders in the Black Country was Thomas Monk,

whose business began at a small boatyard in Tipton. He

had around 130 boats carrying all kinds of goods between

the Midlands, North Staffordshire and London. Thomas was

credited with the introduction of cabins on canal coats.

The boats became known as 'Monkey Boats', a name that

was eventually applied to all boats on the canal that

carried a cargo.

Around 1820 Thomas introduced a

passenger service between Factory Bridge at Tipton and

The Wagon and Horses at Birmingham. He built a specially

designed boat called 'Euphrates', a fly boat with

rounded sides and a keel so that it could travel quickly

through the water. It was of lightweight construction

with a wedge shaped front. The horses travelled at an

unbroken trot and were changed every few miles.

'Euphrates' became known as the 'Monkey Fly Boat' and

was captained by a local man, John Jevan. It operated a

two-hour passenger service from Tipton to Birmingham on

Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, leaving Tipton at a

quarter past eight in the morning, and returning from

Birmingham at 5 o'clock on the same day. It called at

Dudley Port, Oldbury, Spon Lane, and Smethwick. On

Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Fridays it was available for

private hire, and excursions.

In 1830 the service was extended to

Wolverhampton, running daily along the old main line.

After the building of the new main line, 'Euphrates'

also ran from the Packet Inn at Wallbrook to Birmingham

in two and a half hours, through the newly built Coseley

Tunnel. The boat continued to carry passengers until the

Stour Valley Railway opened in 1852. It was then stored

at William Monk's yard at Selly Oak.

William White includes the

following entry in his 1834

History, Directory and Gazetteer

of Staffordshire:

Carrier by Water - William.

Turley, from Highfields to

London, Shardlow, Liverpool,

Manchester, Gainsborough, Hull,

etc.William White includes the

following entry in his 1851

History, Directory and Gazetteer

of Staffordshire:

Swift Packets, four times a day,

with passengers, etc. To Birmingham and Wolverhampton,

call at Deepfields. |

|

Euphrates. |

| Coseley was home to one of the largest canal

carrying companies in the area, which specialised in

transporting chemical waste, such as waste phosphorus

from Albright & Wilson, in Oldbury. Alfred Matty & Sons

were based in the large canal basin, in between Biddings

Lane and Anchor Lane. The basin, although no longer in

use, still survives. The firm, which owned a large fleet

of boats and some motorised tugs was well known in the

area. In the 1980s, the business became part of

Dewsbury and Proud Limited, a crane hire company. |

Some of Alfred Matty's boats, at

the entrance to the canal basin in 1980. In the distance

is Anchor Bridge at the end of Anchor Lane. Courtesy of

Dave Necklen. |

|

Matty's basin and yard. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Churches |

|

Return to

the

Contents |

|

Proceed to

Railways |

|