|

The

Increasing Population & Social Conditions in the First

Half of the 19th Century.

At the beginning of the 19th century,

the overcrowding caused by a rapidly increasing

population hadn't really began. There were sufficient

houses, and employment for everyone. The figures from

the 1801 census are as follows:

|

population |

|

3,812 |

| number

of males |

|

1,996 |

| number

of females |

|

1,816 |

| number

of inhabited houses |

|

703 |

| number

of uninhabited houses |

|

59 |

| number

of families in the houses |

|

777 |

| people

employed in agriculture |

|

35 |

| people

employed in manufacture and handicrafts |

|

1325 |

| people

in other employment |

|

2452 |

During the Napoleonic wars when the gun

trade was booming, local people used to boast that

Darlaston had more money per square inch than any other

town in Great Britain. Money was so plentiful that many

of the people employed in the gun trade used to squander

it, and large amounts of fish and meat were sold here.

Business was also booming for shopkeepers, and many

people seeking employment were attracted to the town,

which continued throughout the century. |

|

Year |

Population |

|

1801 |

3,812 |

|

1811 |

4,900 |

|

1821 |

5,600 |

|

1831 |

6,600 |

|

1841 |

8,200 |

|

1851 |

10,591 |

|

1866 |

12,884 |

|

1870 |

14,724 |

|

1881 |

13,600 |

|

1891 |

14,400 |

|

1901 |

15,395 |

| Even though the population increased, adequate

housing, drainage, and sanitation were not provided

very quickly. This produced an extremely high death

rate, and Darlaston was described as the

unhealthiest town in the black country. Houses fell

into two broad categories, those for the rich, and

those for the poor. The houses for the rich compared

favourably with similar dwellings elsewhere, but

many of the poor lived in dreadful conditions. The

worst houses were those in the notorious courts.

Houses were crammed into any available space, many

being built behind existing houses. As many as ten

houses were built into a courtyard, with perhaps

sixty people sharing common wash houses and toilets.

Some of the very poor had to use boxes as tables and

chairs, and it was not uncommon for people to sleep

on the floor, with sacking and old clothing for

bedding. |

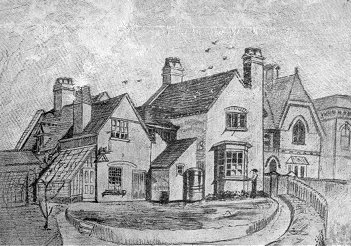

A view of the back of the Adams

family's house in Pinfold Street. On the right is the

Wesleyan Chapel and to its left part of the minister's

house. From the Methodist Recorder 13th June, 1901. |

Coal was the main source of heat and power. Smoke

poured from domestic and factory chimneys in vast

clouds, which created a permanent canopy over the entire

district. Soot often formed a coating on buildings, and

soot spots used to appear on washing hung out to dry.

The coal fires produced large quantities of ash. There

were no sewers, and the toilets were emptied

periodically by the night-soil men, who carried out

their unsavoury task while everyone else slept. The

contents of the toilets were mixed with the ashes, and

transported by wheelbarrow to an awaiting cart in the

street. |

| The refuse was then transported to dumps in various

parts of the town, one of which could be found in

Darlaston Road on the site of the Servis factory. The

smell was extremely unpleasant, as you can imagine.

Accommodation was often supplied by publicans who were

amongst the most affluent members of the community.

Sometimes they provided finance for the building of

houses, but more often they purchased plots of land,

divided them up into streets, and sold building plots to

builders or private individuals. Some of these streets

were named after them; Aldridge Street, Corns Street,

and Foster Street. One such landlord, Charles Foster of

the Bell Inn, purchased a piece of land known as Wilkes'

and Shale's Crofts and divided it up into building

plots. He had roads built and called the development

"Charles Foster's Building estate. Plots were sold by

private contract or at an auction held at the Bell on

2nd May, 1836. This development included Foster Street.

A new parish workhouse opened in 1813 on a site near

the corner of St. Georges Street and The Green. It

closed in 1838 on the formation of the Walsall Poor Law

Union, whose buildings now form the older part of the

Manor Hospital. Their workhouse in Pardoes Lane (now

Victoria Road) was demolished in 1887 to make way for

the Town Hall. The workhouse was established to cope

with the vast numbers of poor and vagrants produced by

an unequal society, and unstable economy. It was not

intended as a shelter, but as a place of work, life

being both unpleasant and degrading.

The Parish Workhouse included a lock-up, an early

prison cell. The Parish Constable in 1838 was Joseph

Golcher and when the workhouse closed he built a new

lock-up at the rear of his own house. This continued in

use until he retired. The town also had a whipping post

and Parish stocks at Rock's Fold near the Bell Inn,

Church Street. When the stocks were eventually removed

they were stored at the house of the acting constable

and later mounted on wheels. Anyone condemned to the

stocks would be wheeled around from place to place as

part of the punishment. |

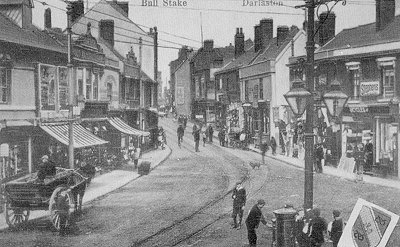

The Bull Stake & King Street

around 1907. From an old postcard |

At about this time the face of King Street was

starting to change. It originally contained many

attractive houses that were occupied by some of the

wealthier citizens. The Poor Law Relief Rate Book of

1800 states that in 1793 there were 50 substantial

houses, and 16 houses combined with some sort of

business. Most of these consisted of small workshops,

and in some cases they had a small retail shop attached,

in which was sold the produce from the workshop. |

Parson & Bradshaw's Directory of 1818 lists 11

retail businesses:

| 2 - |

Butchers |

| 1 - |

Baker & Maltster |

| 1 - |

Shoemaker |

| 1 - |

Linen & Woollen

Draper |

| 1 - |

Tailor |

| 1 - |

Saddler & Coach

Proprietor |

| 1 - |

Warehouseman |

| 3 - |

Shopkeepers |

Throughout the 19th century the houses were gradually

converted into shops, so that King Street became the

principal shopping street, as it is today. As industry

flourished and the population grew, the demand for local

shops increased. The numbers were as follows:

| 1834 - |

17 shops |

| 1845 - |

24 shops |

| 1855 - |

34 shops |

| |

|

|

|

|

Pigot & Co.

1828 directory |

|

Read an 1842

trade directory |

By 1850 a large variety of items could be purchased

in King Street, including; food, clothing, clocks,

watches, footwear, books, stationery, seeds, baskets.

There were 4 chemist shops, 2 house agents, and a fire

insurance agent. By the end of the century only two

houses remained, the others had been converted into

shops.

The row of shops in Pinfold Street were originally

private houses. Half were one up, one down workmen's

cottages. It was here that most of the victims of the

1831 cholera epidemic lived. Behind the houses ran a

ditch, dug to remove waste water from the factories at

Kings Hill. The water ran into a boggy area behind

Catherine's Cross. When it left the factories the water

was fairly clean, but along the way it was used as an

open sewer. By the time it reached Pinfold Street it was

very dirty and contaminated with the carrier of cholera.

There were 223 cases of cholera, and 68 deaths, most of

which were in Pinfold Street. Later, when the danger was

understood, the ditch was deepened, partly culverted,

and diverted into the canal at Porkett's Bridge.

|

| Read about Darlaston in

1851 |

|

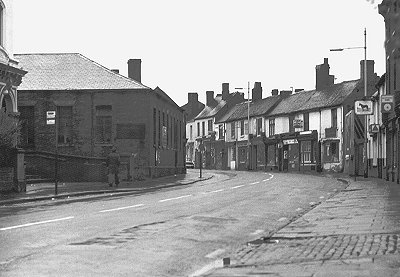

The photograph shows the Wesleyan

Methodist School on the left and the row of shops where

most of the victims of the 1831 cholera epidemic lived.

The Black Horse pub on the right was the oldest public

house in Darlaston, dating from the late 18th century.

It was the headquarters of the town's horse racing

fraternity. |

Pinfold Street in the early

1970's. |

|

King Street from the Bull

Stake in the late 1950s, before its decline.

The shops on the opposite side of the road are L to R:

A. P. Appleyard. The Corner Shop, Collins shoe shop,

Careful Cleaners, and Middleton's Toy Shop.

|

|

|

|

Return to Iron and

Steel Making |

Return to

Contents |

Proceed to The Grand JunctionRailway |

|