| By 1799 a small stone-built blast furnace was

working at Darlaston Green, which must have

formed part of the first iron works in the town. In 1826 Richard Bills a gunlock maker of Church

Street, established a furnace and foundry at Furnace

Lane, Lower Green, where Heath Road is today. He made

his stepson Samuel Mills a full partner on his 21st

birthday in 1826, and the company became known as Bills & Mills.

Richard died on 16th June, 1849, at the age of 72.

Samuel took over the company in February of that year. |

|

Before Richard's death, the

partnership was dissolved. From the London Gazette, 9th

February, 1849. |

|

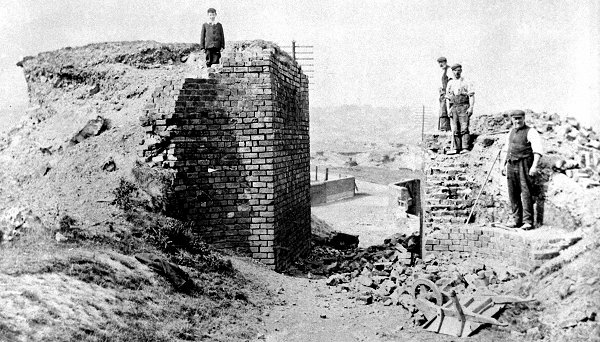

One of the blast furnaces. It

stood on the northern side of the canal, and is seen

here, as it was around 1870. |

| By the 1850s the site covered over 55 acres, on both

sides of the canal. The southern part between the canal

and Heath Road consisted of two blast furnaces, extensive puddling furnaces,

cementation kilns, foundries, a vast metal processing

complex, and Brown's patent rolling mills.

To the north of the canal stood the oldest of the

three blast furnaces and several coal and iron ore

mines. This was one of the earliest, largest, and most

important iron and steel companies in South

Staffordshire, and had a name for good quality iron. The

company also owned a factory at Kings Hill. |

| The furnaces were hand-filled from the top. The tall

brick charging tower on the left of the drawing contains an

overhead gantry, and two hoists to lift barrows of

burden up to the charging platform that ran around the

top of the furnace. Each barrow would have held around

15cwt. They ran on iron plate roads and had two sharp-tyred

wheels that could cut through obstructions that had

fallen onto the plate roads, such as pieces of coke.

The barrows were hand-filled in the ore and coke

pens, and dragged to the bridge of the hoist where the 'cager'

would load the full barrows onto the hoist, and unload

the empties. To start the hoist he rang a bell as a

signal to the engine man who operated the steam engine

that powered the hoist.

At the top was a 'filler' who wheeled the barrows to

the throat of the furnace, lowered the bell that sealed

the top, and emptied the contents into the furnace. He

would then close the bell. At night the furnace top and

the surrounding area was lit by the waste gases burning

at the 'monkey', a bypass pipe on top of the bell. |

|

|

Furnace charging mechanism. |

|

The furnaces had a hot blast that was produced by a

steam engine. The blast passed through large cast iron

pipes that went through brick, coal fired, heating

stoves. Two of them (one on either side of the furnace)

can be seen in the top drawing. In between to the two

chimneys on the left of the drawing is one of the engine

houses. It contained two 70 hp. beam blowing engines,

one of which also operated the hoist. The site had a

horse-drawn narrow gauge tramway. Slag was poured into

slag ladles, which were hauled by a team of three horses

to the tip. Each ladle had a tipping mechanism that was

operated by a quick release shackle.

All sizes and shapes of iron plates and bars were

produced including boiler plates, hoops, strip, tank

plates, rails, wire rods and small sizes of rounds and

squares. All kinds of steel were made using the

cementation process and these were well known and

appreciated in the market. |

The charging tower, blast furnace,

engine house, and heating stoves. From an old postcard.

A view from the other side of the

furnace. Also from an old postcard.

Samuel Mills became a

wealthy man, thanks to the success of Bills & Mills,

and the earnings from his many collieries in the

area. In 1855 he leased the Essington Wood Colliery

which was situated on the western side of Bursnips

Road, Essington. He purchased the colliery in 1860

and ran it as a separate business alongside Bills &

Mills. The company eventually employed around 2,000

people.

On 3rd August, 1863 Samuel Mills sold the ironworks,

collieries, and plant to Samuel Lloyd, Joseph Foster

Lloyd, Wilson Lloyd, and William Henry Lloyd, for a

quarter of a million pounds, which led to the formation of the Darlaston

Steel and Iron Company. |

The company's seal.

|

The Darlaston Steel &

Iron Company's works between the canal

and Heath Road. |

Mr. Sampson Lloyd of Wassel Grove, Stourbridge became company Chairman with

Mr. Francis Lloyd as Managing Director. The business was

re-registered as the Darlaston Steel and Iron Company on

7th November, 1872 and rapidly expanded. The number of puddling furnaces grew

to 43 with 17 reheating furnaces, 8 rolling mills, a

drawing-out forge, 63 steam engines, including the three

70h.p. blast engines for the blast furnaces, and rails,

which

were laid to all parts of the works. The rolling mills required very little manual labour

and could automatically roll enormous quantities of

strip in great lengths using Brown's patent process,

where the strip being rolled is automatically passed

through a second pair of rolls to complete the work.

There were two of Casson's patent puddling furnaces

and a Griffiths mechanical puddling machine, which worked well

together. The company's collieries and mines, mining a 12

yards thick seam, covered 850 acres, 350 of which were

freehold and 500 leasehold. Some of the seams produced

what was called "Brooch" coal and others "Heathen" coal.

There were also ironstone mines thanks to thick seams of

"Gubbin" ironstone, "New Mine", Whitestone", and "Blue

Flats" ore.

The iron industry as a whole felt the effects of the

depression between 1875 and 1886 during which many blast

furnaces, forges and mills closed. The Darlaston Steel

and Iron Company was also badly effected and closed in

1877 as can be read in the announcement below:

|

Another of the blast furnaces.

Another of the blast furnaces.

| After the closure, Francis Lloyd brought a disused

timber yard at James Bridge, and established a small

foundry which eventually became F. H. Lloyd's James

Bridge Steel Works.

In 1877 the Darlaston Coal and Iron Company

(registered on 19th September, 1877) took

over the Darlaston Steel and Iron Company's works

with Ironmaster John Jones in charge. In 1878 he was

replaced by E. Gem. At the same time A. E. Wenham became company

secretary. The company also ran the Essington Wood

Colliery which rapidly expanded with the opening of

two new shafts, a coal screening plant, and a

railway siding.

In 1882, during the depression in the iron trade, the

Darlaston Steel & Iron Company went into liquidation

and was auctioned at Wednesbury Town Hall on 27th

February, 1882. The coal

company decided to concentrate on the mining

operation at Essington, where in 1891 the colliery

became Holly Bank Colliery, with the formation of

the Holly Bank Colliery Company Limited.

The 1882 sales plan of the

works.

| William Henry (Harry)

Richards, grandson of

Charles Richards of Imperial

Works, mentions the

following in his memoirs:

Lot number 4 was bought

by George Braithwaite Lloyd,

who bought debentures from

the old iron works. In turn

it was bought by Thomas Tolley, of 47 Broad Street,

Bilston, for £5,000 on 7th

November, 1882. On 20th May,

1884, Mr. W. H. Bostock of

Burslem bought a one third

share for £5,000, as did

Richard Mentz Tolley. They

traded as Tolley, Sons &

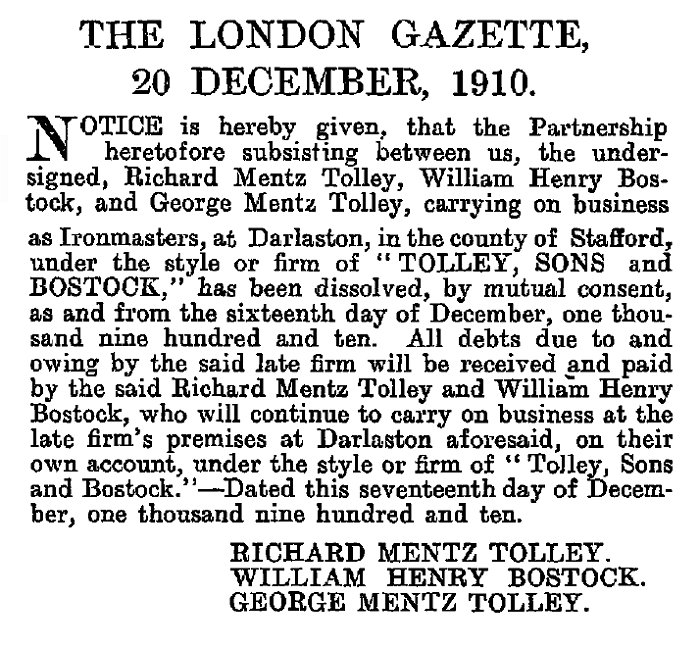

Bostock. |

|

The two newer iron-bound brick blast furnaces on the

northern side of the canal continued to be used.

They had a charging stage, lift, and hot air oven

43ft. long, 18ft. wide and 23ft. high. In 1891 the part

between Heath Road and the canal was acquired by Charles

Richards for his Imperial bolt and nut works.

In 1900 the construction of a new steel-clad

blast furnace began. It replaced the two stone-built

furnaces on the northern side of the canal, and came

into operation in 1902. By 1905 two Cowper blast

heating stoves had also been added. The old heating

stoves were kept as a stand-by for use in

emergencies, until about 1920 when they were

demolished. By the early 1900s the local iron ore

would have been depleted and so scrap iron must have

been used instead.

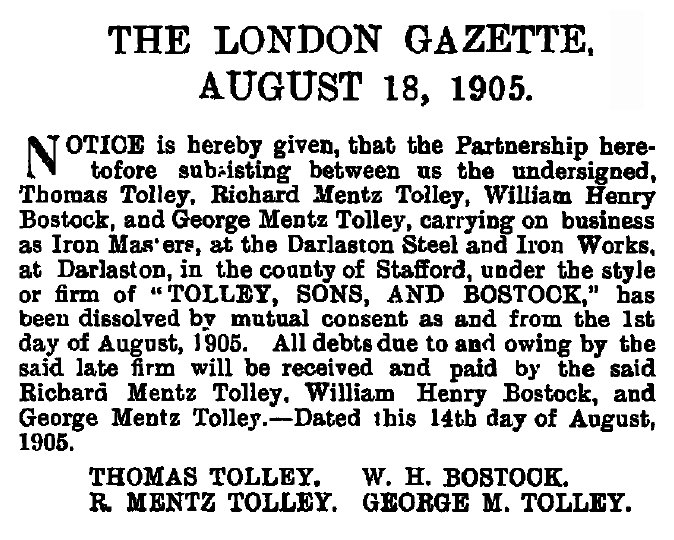

In 1905 Thomas Tolley

resigned.

In 1910 George Mentz Tolley

sold out for £3,288..

In 1910, W. J. Foster joined the company as a foreman

and by 1914 had become works director. Around the

end of the First World War Rubery Owen & Company

built and installed a new blast plant at the works

with a double bell top, inclined skip charging, and

a travelling overhead crane over the ore and coke

pens. The ambitious scheme was never completed

because the demand for pig iron fell. The furnace

remained until the late 1930s

when it was dismantled for scrap. Around the same

time the last surviving charging tower was

demolished.

An aerial view

showing the furnace built by Rubery Owen

& Company. From the collection of the

late Howard Madeley. |

Another view

of the furnace built by Rubery Owen &

Company.

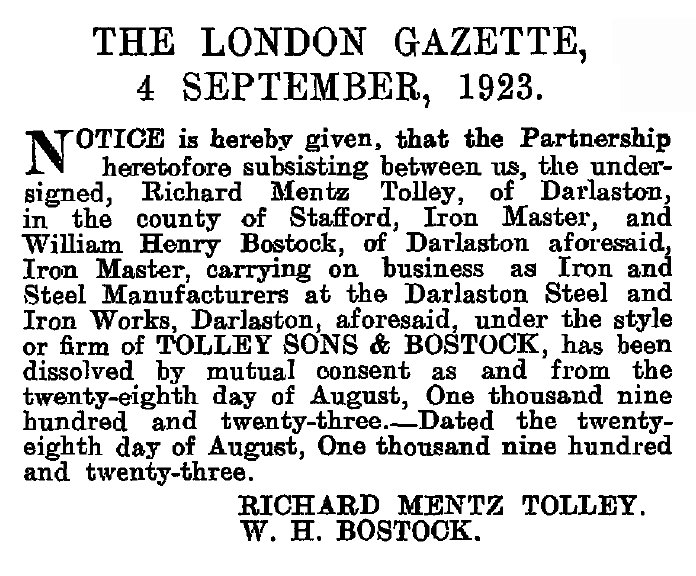

| On 28th August, 1923, F. W.

Cotterill Limited, then part of

G.K.N. bought Tolley Sons & Bostock

for £16,500 in order to gain control

of their steel supplier. The firm

then became Tolley Sons & Bostock

Limited. The factory carried out all of G.K.N.'s puddling

and rolling operations for their nuts, bolts and

fastenings department, but by then the plant was

very old fashioned and so G.K.N. eventually sold

the works. |

|

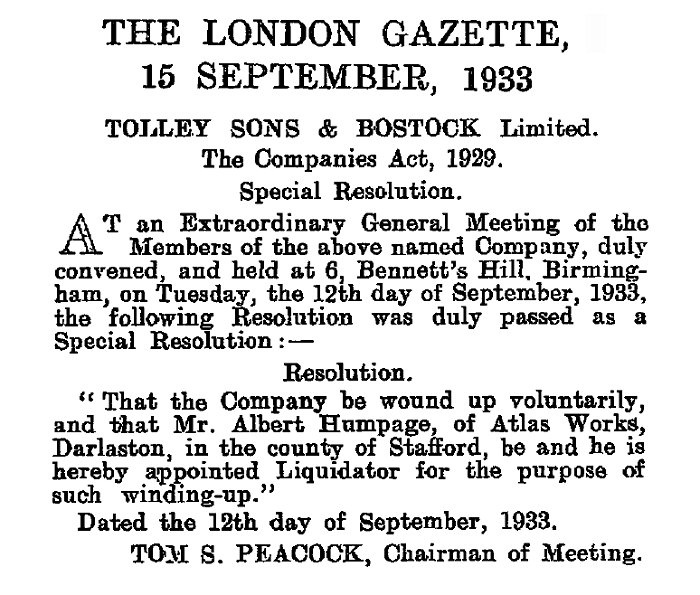

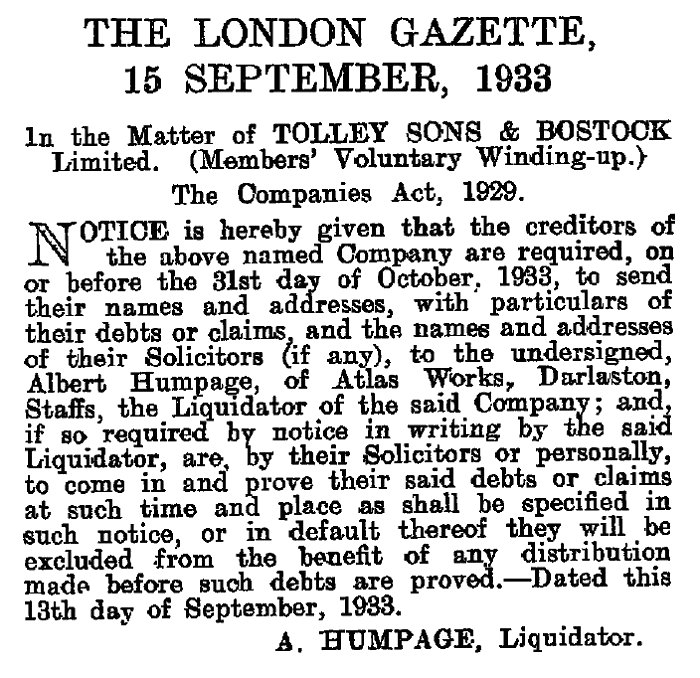

GKN decided to liquidate Tolley Sons

& Bostock Limited in 1933:

|

| William Henry

(Harry) Richards,

grandson of Charles

Richards of Imperial

Works, recalls the

Tolleys in his memoirs,

written in the early

1960s: I do not

remember Mr. Thomas

Tolley, but he lived at

the top of Victoria

Road, opposite the

Parish Church I believe.

He was a boiler maker

by trade and used to get

inside his boilers and

do his own repairs on

Sunday mornings. Mr. Bostock used to be a

smart man in his youth

and lived in Avondale

Road, Wolverhampton and

was a Good Templar at

one period in his life.

Richard Tolley was a

'cocky' individual, he

married Nelly Horton,

daughter of Enoch Horton

who built The Grange at

Bescot.

George Tolley was a

good practical man, but

drink ruined him. He

used to have a bottle of

stout for his breakfast.

He lived at The Beeches,

Bescot, which I believe

is now a dairy. At one

time he lived at the

White house, now part of

E. C. & J. Keays.

In the early days

they used to have a

small loaf and a quarter

of corned beef for their

dinner.

I remember both

Tolleys well and Mr.

Bostock. After George

Tolley was paid out, he

became Night Manager for

a time on condition he

left the counter I

believe. He went to live

in Alexandra Road, Penn.

His son was a good

'plucked un', he came to

the works and did his

stuff on the rolling

mills in clogs and

moleskin trousers. I

used to bike home with

him sometimes.

George and his family

went to Canada and his

son joined the forces in

the First World War and

came to England again. I

haven't heard of him for

years.

Richard went to

live at Windsor, but

both he and W. H.

Bostock have passed

away. There used to be a

good school of 'em, my

uncle William Richards,

owner of the foundry,

now Wilkins and

Mitchell, George Wiley,

George Tolley, and my

uncle Silas, father of

Fred Richards of Nuts

and bolts Limited, and

C. P. Robinson, the

proprietor of

D. Robinson & Sons, the

oldest firm in the town.

This was the forerunner

of Nuts & Bolts Limited.

I have heard my

mother say that once

when the Tolleys had a

breakage of a large

wheel, old Mr. Tolley

came into the shop and

cried when he said he

would be ruined.

I have to thank Robin

Richards for the copy of

Harry Richards' Memoirs. |

|

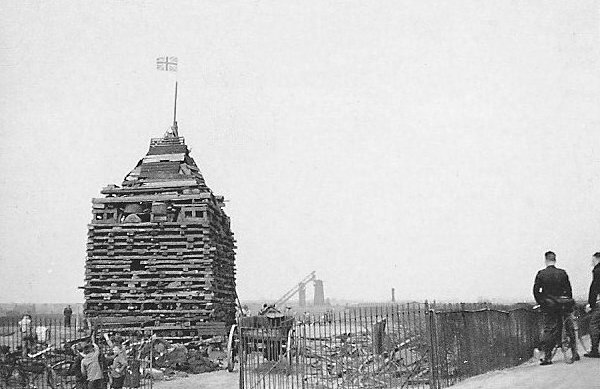

A photograph of

the bonfire on The Flatts to celebrate

the Coronation of King George VI on 12th

May, 1937. The furnace and charging

tower can be seen in the middle

distance. Photographed by the late W. J.

Ashmore. Courtesy of John & Christine

Ashmore. |

|

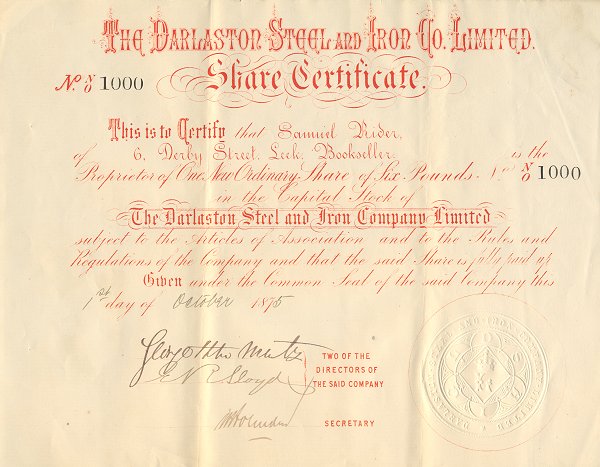

A share certificate dated October 1875.

The first page of the July 1873 price list.

| The site was sold to Bradley and Foster

Limited, who were there for many years. |

| |

|

| Read about Bradley & Foster

Limited, the largest producer of refined pig iron in the

country |

|

| |

|

Samuel Mills and his

familyThe family lived in Darlaston House on

the western end of what is now Victoria Park, where

Samuel died in 1864. The house and its surrounding land

occupied the modern Rectory Avenue, the Post Office, and

the area behind Pardoe's Cottage, where the dovecote

still stands. In the 1920s when foundations were dug for

the war memorial in Victoria Road, the ground gave way

to reveal part of the cellars of Darlaston House. The

workmen found a number of bottles of wine, much of which

was drunk there and then, although some bottles of

parsnip wine did find their way to The Green Dragon in

Church Street, were they went on sale. The original All

Saints Church in Walsall Road was built in 1872 in

memory of Samuel Mills, who died in 1864.

Jane Mills,

one of Samuel's daughters, was a public spirited lady

who did much for the town. She founded the Jane Mills

Institute in Rectory Avenue, in connection with the

Parish Church to help the needy women and girls of the

town. The building housed the institute and was given to

the town when Jane moved to Whitton Court, Whitton, near

Ludlow, in the late 1890s. The institute, later known as

the "Mothers Meeting and Girl's Institute" eventually

became a clinic and later "The Sons of Rest". The

building is now a family home.

Rough Hay Furnaces

Rough Hay Furnace & Foundry, Darlaston Green, was

founded on 27th August, 1842 by Edward Addenbrooke

Addenbrooke of Kingswinford, Thomas Smith of Cheltenham,

and Charles Pidcock of Worcester. The firm was managed

by Edward and two of his sons, John and George

Addenbrooke. The firm traded as Addenbrooke, Smith & Pidcock,

coal and iron

masters.

The family was descended from the Addenbrookes of Wollaston

Hall, Stourbridge. Their father, Edward Addenbrooke, and

grandfather, John Addenbrooke Homfray were both

ironmasters.

Family background

John and George Addenbrooke were descended from a

long line of ironmasters going back to the early 18th

century. It started with their great, great grandfather

Francis Homfray who owned two forges, and a slitting

mill in South Staffordshire. The family lived in style

at Wollaston Hall which stood on the western side of

Stourbridge.

John and George had family links with the huge iron

industry in South Wales. Their great grandfather's

brother Francis Homfray had three sons, Samuel, Thomas

and Jeremiah. Samuel and Thomas founded a large iron

works at Penydarren, on the banks of the Morlais Brook.

They also built a mansion nearby called Penydarren

House. Samuel is best remembered as the promoter of

Richard Trevithick's Penydarren locomotive, the

first locomotive in the world to run successfully on a

railway. The test took place on the Merthyr Tramway

which ran for 9½ miles from

Merthyr to Abercynon. It managed to haul five

wagons carrying ten tons of iron, and seventy men, at a

speed of five miles an hour. Samuel was one of the main

promoters of the Glamorgan Canal, and founder of the Tradegar Ironworks. He became High Sheriff of

Monmouthshire in 1813, and in June 1818 became Member of

Parliament for Stafford. His brother Jeremiah was one of

the founders of the Ebbw Vale Ironworks.

In 1787 John and George's grandfather John

Addenbrooke (Homfray) and his cousin Francis obtained a

lease for Lightmoor Ironworks which had two furnaces,

and stood roughly halfway

between Dawley and Ironbridge. In 1797 they obtained a

lease for the Lightmoor coal mines, and also ran the

Little Dawley coal mines. They operated the Little Dawley

mines until 1822, and Lightmoor Ironworks until 1839.

Francis was also a partner at Calcutts Ironworks near

Broseley, Shropshire, where amongst other things he made

cannons for the

American Civil War. As well as blast furnaces, he also

owned blade mills, slitting and plating mills, finery, chafery, balling furnaces, rolling mills, and forges.

John Addenbrooke's surname was originally Homfray. In

1792 he had it changed to Addenbrooke, his mothers'

maiden name.

John and George were born in Kingswinford, and had

three brothers and six sisters. Their father was Edward

A. Addenbrooke (1782 - 1855) who married Emma

Pidcock (1794-1875) in January 1815 at Old Swinford. She

came from Coalbourne Brook, near Stourbridge. In 1851

they were living in Dudley Road, Kingswinford and had

eleven children:

Edward, John, Emma, Elizabeth, Henry, Emma, George,

Thomas, Laura, Frances, and Henrietta.

John was born in 1817, and George in 1825.

1851 census: Dudley Road,

Kingswinford:

Edward A. Addenbrooke (age 69 born

Oldswinford), Iron Master employing 300

men.

His wife Emma Addenbrooke (age 57 born

Oldswinford).

Children:

Henry Addenbrooke (age 29 born

Kingswinford), Solicitor.

Priscilla Addenbrooke (age 21 born

Kingswinford).

George Addenbrooke (age 25 born

Kingswinford), Iron Master.

Thomas Addenbrooke (age 24 born

Kingswinford), Solicitor.

Laura Addenbrooke (age 22 born

Kingswinford).

Three servants. |

|

The family's ironworks and collieries in

Darlaston and the surrounding area

For several

years Edward A. Addenbrooke and three of his

sons, Edward, Henry, and John ran the Moorcroft Ironworks at Bradley,

which had two furnaces, and produced around 100 tons of

iron each week. They also ran Moorcroft Colliery and

Bradley Hall Colliery, both linked to the ironworks by

tramways. The businesses were sold in 1841. Edward A. Addenbrooke

is listed as the owner of Brickfield Mine at Rough Hay,

Darlaston, in the list of owners and occupiers that

accompanied the 1843 tithe map of Darlaston. The list

also includes details of the many fields that he owned

at Rough Hay, along with several pieces of land beside

the canal, known as Canal Bank, Rough Hay Bridge and

Long Bridge Piece.

Their ironworks at Rough Hay, Darlaston,

founded on 27th August, 1842, became very successful.

The brothers developed and patented a system for

extracting hot combustible gases from the top of the

furnaces, and used them to heat the air for the blast,

and to generate steam for the blast engine, which also

operated the hoist to lift the coal and iron ore etc. to

the top of the furnace. This technique enabled iron to

be produced more quickly and cheaply, because the

furnace remained at full operating temperature during

the blast.

|

|

They also developed calcining kilns in which

the iron ore was heated by coal fires to heat the iron

ore before smelting. The process, which removed carbon

dioxide and water from the ore, and oxidised it, was

much cheaper to run than the traditional method, in

which the ore was calcined in open mounds. |

| George Addenbrooke married Matilda Louise Westwood at

Wombourne in 1854. They lived at Greenhill House in

Wombourne, and their son George Leonard Addenbrooke,

born in 1860 had a distinguished career in electrical

engineering. John Addenbrooke married Elizabeth, and they had

eleven children. In 1851 they were living in Birmingham

Road, Bromsgrove, and by 1871 had moved to The Elms,

Sutton Road, Walsall. In the 1881 census their address

is given as Waterloo Terrace, Newhampton Road,

Wolverhampton.

After 1855, when Edward Addenbrooke died,

John and George ran the business on their own. Addenbrookes were Darlaston's second largest employer, until the

business closed at the beginning of 1882,

putting over 1,000 people out of work. They had three

blast furnaces at Rough Hay, all traces of which have

now disappeared. Their products included bar, rod and

sheet iron.

Addenbrooke, Smith & Pidcock also owned Rough Hay

Colliery, one of the largest coal mines in the area,

employing 500 people.

John and George owned many

collieries in the area, including a number at Leabrook

in Wednesbury, and the Bedworth Coal and Iron Company

Limited in Warwickshire.

|

|

Both sides of an Addenbrooke, Smith & Pidcock

token. Courtesy of

George is remembered by the street that

is named after him; Addenbrooke Street. He was a founder

member of the Darlaston Local Board (the forerunner of

the council), a member of the Institute of Mechanical

Engineers, and churchwarden at St. George's Church. In fact

the Addenbrooke company gave the land on which St. George's

vicarage was built. He died on 20th May, 1906 at the

vicarage in Chalford, Stroud and was buried at St.

George's Church, Darlaston.

The photograph shows

the demolition of a bridge and tramway in

Rough Hay. The opening under the bridge was

known as "The Khyber Pass" and is

commemorated today by the street named

"Khyber Close". The old tramway must have

been the one that ran between Addenbrooke, Smith & Pidcock's

factory, Rough Hay Colliery, and a canal

basin. The dirt track under the bridge is now

Hall Street, and the bridge beyond crosses

another tramway that ran between two of the

coal mines. The view looks southwest towards

the Dudley-Sedgley ridge. |

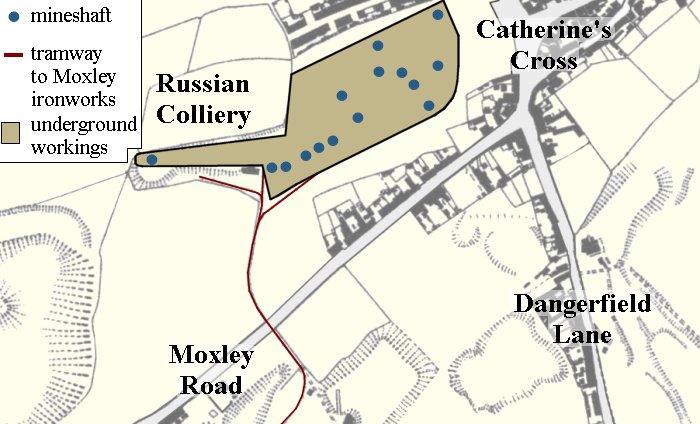

| A map showing the

location of "The Khyber Pass" and Addenbrooke, Smith & Pidcock's

factory, which stood roughly at the junction

of Rough Hay Road and Hall Street.

At each end of the

lower tramway was a winding machine.

There were many

abandoned mine shafts and spoil heaps in the

area, which would have looked very different

to today's flat landscape.

The council must

have had an immense task clearing the area

when the pre-war council estate was built. |

|

George Addenbrooke's lovely

home, Greenhill House, in Wombourne.

The Albert Works and Moxley Iron

Works The Albert works were built in 1827

and run by David Rose. The Moxley Iron Works were

founded by brothers Daniel and David Rose in 1830.

Daniel retired in the early 1840s and the younger David

ran both of the works. The works produced iron forgings

and charcoal sheet iron of all kinds that was used for

such things as boiler plates and gasometer sheets.

Galvanising and corrugating were carried out on a large

scale at the works and all kinds of bars including small

rounds and fancy iron were produced. Other products

included pan and tank plates, galvanised and corrugated

sheets, and pig iron. The Victoria Works, founded by

William Molineaux and James Jordan were also on the site

producing strip iron for such things as locomotive and

boiler tubes. |

|

The location of the works. |

Two blast furnaces were added in the 1840s and could

turn out 20,000 tons of pig iron annually. David Rose owned a number of mines in the area and the

site included a sand pit were sand was dug and sold for

use in blast furnace and mill furnace bottoms. The clay

from some of David's mines produced high quality fire

bricks and these were one of the company's many

products. The mines also contained sufficient coal to

supply the works for 20 years. By the1870s there were 40

puddling and ball furnaces, 5 sheet mills, 1 plate mill,

1 bar mill, and one hoop mill. |

| Samuel Griffiths included the following description

of the iron works in his 'Griffiths’ Guide to the Iron

Trade of Great Britain', published in 1873: |

|

The Albert and Moxley Iron Works

The former of these works

were built twenty-one years ago, and have since

been carried on by Mr. David Rose. The Moxley

Works, which were formerly carried on by Messrs.

Daniel and David Rose, were founded in 1830, but

on the occasion of Mr. Daniel Rose retiring from

business a few years ago, the whole of the

property was acquired by his youngest brother,

Mr. David. These works are justly celebrated for

the manufacture of use iron forgings and

charcoal sheet Iron.

The Victoria Works are

famed for the manufacture of all kinds of strip

iron, notably that for locomotive and boiler

tube purposes. The Albert Works, like Mr.

William Rose of Batman's Hill, stand well in the

market for plates and sheets, and the firm have

a good old connection with engineers and

machinists at home and on the continent of

Europe. Two blast furnaces have recently been

built here on most modern principles, and

acknowledged to be the finest plant in the South

Staffordshire District, and capable of turning

out 20,000 tons of pig iron per annum.

Mr. Rose has extensive

galvanizing works here, and carries on the trade

on the same premises to a large extent. Although

Mr. Rose is an old ironmaster, his judgment in

mines is very sound. On more than one occasion

he has purchased valuable mineral property in

the Black Country, and sold it at a large

profit.

It may be interesting to

note that near the works is a valuable sand

mine, largely used for blast furnaces and mill

furnace bottoms. It will thus be seen that

whilst the sand in being excavated forms a nice

little revenue, it is a valuable adjunct to the

works for the deposit of cinders and ashes. The

mines of coal and ironstone here, and at an

adjoining colliery of about 100 acres in extent,

are also very prolific. Clay for the manufacture

of fire-bricks is also raised, and the quality

is very superior. It is estimated that there is

sufficient coal for the supply of the works for

at least twenty years.

This is a most unique and

valuable property, for Mr. David Rose, of

Moxley, digs his own coal, sand and fire clay,

makes his own pigs and fire-bricks, puddles his

own iron, makes and galvanizes his own sheet

iron, and, we believe, raises a large portion of

the ironstone to make the pigs. We can safely

say there are no other works in England, or the

world, which can boast of the same products and

advantages on one and the same spot, stretching

over an area of comparatively only a few acres

of ground.

The works, which are

connected with the London and North Western

system, are entirely surrounded with a high

brick wall, and are exceptionally convenient and

well laid out. In all there are 40 puddling and

ball furnaces, 5 sheet mills, 1 plate mill, 1

strip mill, 1 bar mill, and one hoop mill. The

pig iron made here is good. Indeed all the iron

made at the Moxley Works, including their

galvanized sheets, stands high in the London

market. |

|

|

A map based on the 1885 O.S. map showing the many

tramways connecting the iron works to the coal mines,

and sand and clay deposits.

The railway line in the bottom

right hand corner joins the London & North Western

Railway's Darlaston Branch, near the junction of

Holyhead Road and Portway Road. |

|

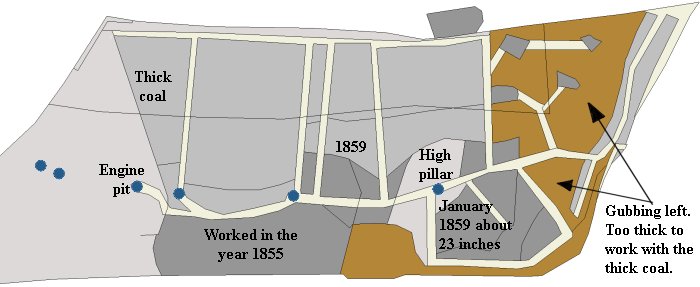

A plan of the Russian

Colliery. |

| The Russian Colliery was founded and operated by

the Rose family. I first came across the name

Russian Colliery as a child, and have since been

puzzled by the name. I remember playing on the spoil

heap as a child, at the top of Woods Bank Terrace.

At that time the two shafts next to Shaw's scrap

yard were still visible. They had been capped, but

were starting to subside a little. When my mother

was a child the shafts were still open, and she

remembered throwing stones into them and listening

for the splash as they landed in water at the

bottom, far below. The puzzle about the name now

seems to have been answered. One of the descendents

of the Rose family is a geneticist who has been

analysing his own DNA. It seems that the family is

of Russian or Ukranian Jewish origin. He has matched

his DNA to members of the Rosenzweig family, so at

some point in time the British members of the family

changed their name to Rose. Which is presumably why

it was known as The Russian Colliery. |

|

Another plan of the colliery,

based upon a contemporary diagram. |

| There were fifteen shafts in all. The colliery

worked from around 1855 until sometime after 1870.

There was thick coal, 4.42 metres in thickness and

18 metres deep. Below this was heathen coal, 0.76

metres thick and 31 metres deep. There was also 'new

mine' coal 4.15 metres thick and 68 metres deep,

along with ironstone, 1 metre thick, and 43 metres

deep. So the site was very productive. |

|

An advert from the early 1870s.

|

An advert from 1861. |

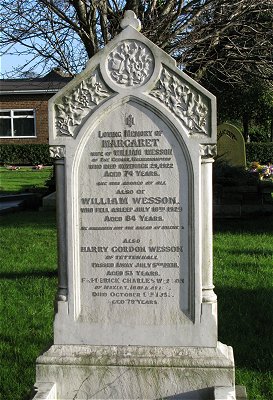

Victoria Ironworks was acquired by William Henry Wesson

in 1898 and he ran the works under the name of Wessons.

William died in 1936 and is buried in the graveyard at

All Saints' Church, Moxley.

Wessons became known as Ductile Wesson, a part of Niagra

LaSalle (UK) Limited.

| |

|

| Read the story

of the Rose family and

their ironworks at Moxley |

|

| |

|

In January 2009 the company announced

that the future of the factory was in doubt,

putting around 150 jobs in the balance. A

further announcement, made in February,

confirmed that the factory would close by

the end of the year, and 63 jobs would

go by the end of April. The factory, which

covered the site of both the Victoria Ironworks

and the Albert Ironworks was demolished in 2011. A large scrap yard and housing

estate now occupies the site of the Moxley Iron Works. |

|

William Wesson's grave

at Moxley. |

Bull's Bridge Iron Works

Bull's Bridge Iron Works were situated in Bull Lane,

Moxley, next to Bull's Bridge on the Walsall Canal. They

were owned by E. Cresswell and Sons, and put up for sale

in November 1859.

The factory covered just over one

acre and included eleven puddling furnaces, a bar mill,

twelve other furnaces, a large cinder kiln, and a 25 hp.

steam engine to drive the machinery.

Adjoining the main

factory was a double office, a smith's shop, a

store room, stable and coach house.

The site was acquired by William Molineux & Company, and

listed in 'Griffiths' Guide to the Iron Trade of Great

Britain', published in 1873, as having 10 puddling

furnaces and 2 mills and forges. The firm mainly

produced sheet iron.

|

| The notice of the

sale of Bull's Bridge Iron Works on 19th

December, 1859. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to New

Roads and a Canal |

Return to

Contents |

Proceed to

Increasing Population |

|