| The Early Years

Alfred Owen was passionate about anything mechanical, and

always kept an eye open for new possibilities and products,

especially items that were not produced in any quantity

elsewhere. In the late years of the nineteenth century, a

revolution in transport in the form of the motor car was

just starting. |

| Within a few years the early prototypes had evolved

into useable and reliable machines. As more manufacturers

appeared, it became certain that the new form of transport would

soon dominate the roads. Alfred Owen realised what the future

had in store, and decided that the firm should get

involved in the transport revolution as a parts supplier

to the many up and coming vehicle builders. In the

factory yard he made a prototype chassis framework from

rolled channel and tubing, which greatly interested the

growing motor trade.

The vehicle chassis began to sell,

and the list of customers grew. Alfred could often be

seen at the bench, with sleeves rolled-up, helping to

put the finishing touches to urgently needed frame

assemblies. He was delighted with the idea that his Darlaston-made chassis would be

travelling up and down the country in all kinds of vehicles.

He was an early motorist himself, and was the first man

to drive a car into Aberdovey,

North Wales.

Other than the early factory building and the partly

covered yard, there was a small two-roomed office where

the partners did their clerical work. |

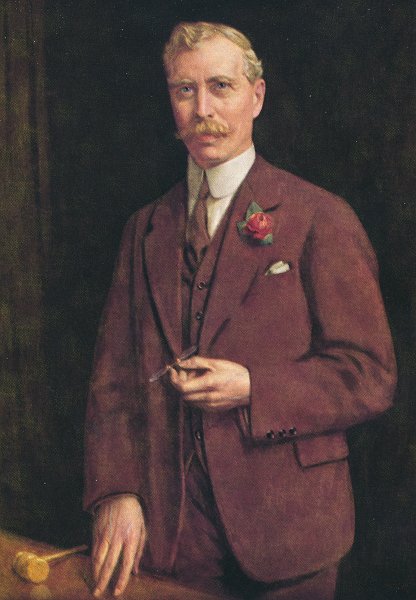

Alfred Ernest Owen. (1869 to 1929) |

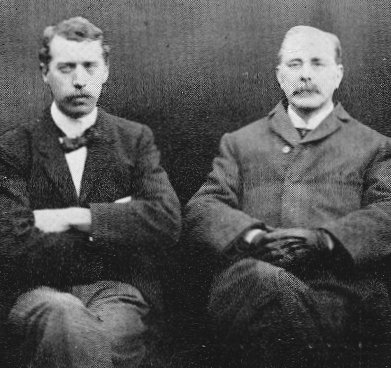

Mr. A. E. Owen (left) and Mr, J.

T. Rubery in 1899. From the April 1947 edition of the

staff magazine "Goodwill". |

They were assisted

in the office by three employees. The first, Charles Guy, the

firm’s draughtsman, also produced the technical specifications.

The second, John Jeavons, the cashier, also helped with the

bookwork and general routine. The third member of the office

staff, young George Buckley, was an eager office junior. At

the side of the factory was a large pool, said to be at

least twenty five feet deep. It occasionally rose

and fell as if it had a tidal system of its own. The extent of

rising and falling was registered by an upright piece of

tee-iron at the water's edge, with markers at every foot. In

warm weather some of the employees would cool-off by taking a

swim. There were many fish including perch, two fine preserved

specimens of which, could be seen for many years in one of the

firm’s offices in Booth Street. |

|

Hard factory work, particularly in the

summer, would bring-on a great thirst, so workers often flocked

to one of the many public houses in the area. Sometimes workers

would be late returning from their lunch break, so someone had

to be sent out from the factory to order them back to work.

This task was occasionally performed by Alfred Owen himself, who on

discovering the culprits, simply took out his watch, and gave

them a time limit to empty their tankards and get back to work.

The factory had its own guard dog in the

form of Leo, Mr. Rubery’s mastiff. In work hours it resided in a

large cage by the factory entrance, but at night it lay in a

sheltered spot in the yard, ready to pounce at the faintest

sound.

In 1899,

Rubery and Co. were awarded a Gold Medal at the

Richmond Exhibition for a chassis frame assembled from rolled

sections and solid round steel bars.

|

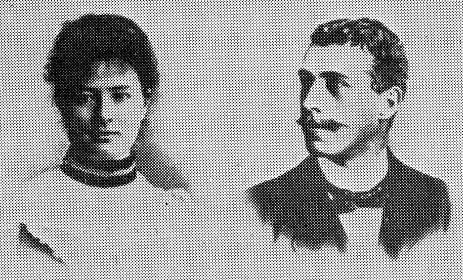

| On 27th June, 1900, Alfred Owen married

Miss Florence Lucy Beech, and they moved into their first home at

Bescot. In August the employees celebrated the event with a

Saturday trip to Codsall Wood, travelling the eight or so miles

on horse-brakes. The celebration, including dinner, was held in

a large tent. Mr. Rubery toasted the newlyweds, and the

afternoon was spent in a series of games and races organised by

the more athletic members of the party. |

Mr. & Mrs. Alfred Owen. From the

summer 1954 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

Alfred Owen was an excellent salesman and

company ambassador. He often visited manufacturers to offer them

his company’s services, and gained an excellent reputation by

scrupulously fulfilling their orders. He realised that motorcar

production would become a national industry and so pursued his

ideas on improving the manufacture of chassis frames. In 1902 he

installed a hydraulic press to produce the first pressed steel

chassis made in this country, and two years later new workshops

were built to house the Motor Frame Department, under the

management of Mr. Albert F. Wilkes. In the same year the Fencing

Department opened.

An advert from 1905, just before the name

change.

An advert from 1908.

Alfred Owen was far more active in

the business than his partner. He clearly felt it was

time to renegotiate the terms of the deed of

partnership, and so talks between the two partners began

on the matter in 1903. After two years an agreement was

reached, and on 7th September, 1905 a new deed of

partnership was signed, and the firm changed its name to Rubery,

Owen & Company. In 1910, John Tunner Rubery, who was getting-on in

years decided to retire. He had no son to follow him

into the business, and so he resigned from the

partnership and sold his interest in the company to his

partner. It took Alfred Owen five years to pay what he

owed. John Tunner Rubery died in Walsall in 1920.

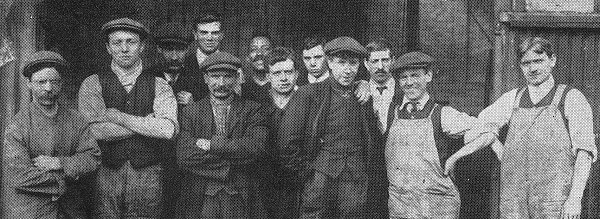

Some employees in 1910. From the

spring 1948 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill".

Alfred soon began to expand the

business and extend the product range. Because he saw an

increasing demand for bright bolts and nuts, and turned parts

for vehicle manufacturers, he added new machinery and plant for

their production, and employed both male and female workers in

the new section. |

|

The early factory. From a 1914

letterhead. |

He also foresaw the development and growth of

the aeroplane, and so opened an Aviation Department to supply

manufacturers with parts. By 1911 the firm had issued a

small catalogue of metal aircraft components. In 1910 the product range included

structural steelwork, motor car and aircraft components,

pressings and fabrications, agricultural products, propane gas

cylinders, and nuts and bolts. |

| Many of the larger machines at Victoria

Ironworks were made by a local Darlaston firm, Wilkins and

Mitchell. Alfred Owen was a friend of Walter Wilkins, the clever

engineer who designed the Wilkins and Mitchell machines. |

| |

|

| Read about slightly unusual

Rubery Owen products from 1911, for water treatment. |

|

| |

|

|

In 1911 Walter and Alfred conceived the

idea of a massive forming press to cold press vehicle chassis

frames, so revolutionising production. Chassis frames were made

from around 10 gauge steel, and until that time had been pressed

hot. Although several similar presses were in use in the U.S.A.

nothing on this scale had been attempted here. The 1,500 ton "upstroking"

hydraulically operated press, costing £2,000, was installed at

Rubery Owen’s Darlaston factory in August 1913 and became an

immediate success. It worked so well that it continued in

operation until 1970, and can be seen today in the car park at

the Black Country Living Museum. Plant was also installed for

the production of larger vehicle chassis, and for components

such as brake drums and rear axle casings.

In 1912 the success of the huge press, and the close

relationship between Walter Wilkins and Alfred Owen led them to

go on a fact finding tour of the U.S.A. to explore the latest

developments in machine tools. Walter had always been impressed

with American engineering and their seven week tour would

provide plentiful opportunities to examine the latest machines.

It nearly ended in disaster because they

booked their passage on a brand new luxury ship, RMS Titanic,

but luckily last minute business commitments forced them to

delay their departure. Had they not done so, the history of

manufacturing in Darlaston would have been very different, with

the possible loss of two of the town’s most important

manufacturers.

|

| Thanks to the delay, they sailed on RMS

Lusitania and after arriving safely, visited many of the leading

American machine tool manufacturers. They also inspected some of

the factories belonging to the largest vehicle manufacturers

including Ford, General Motors, and Studebaker.

As a result of

their successful tour, Alfred Owen conceived the idea of

producing vehicle chassis and other motor components for British

vehicle manufacturers at highly competitive prices. Similarly

Wilkins and Mitchell would go on to build competitively priced,

state of the art machines for the same manufacturers. |

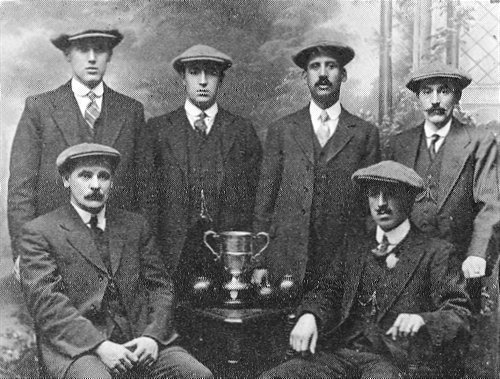

One of the works bowling teams in

1915 with the A. E. Owen Bowling Cup. From the spring 1950

edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

By 1912 there were five departments, each

treated as a separate profit centre:

Aviation, which included the

production of straining screws, eyebolts, clamps, bolts and

nuts, and engine housings.

Engineering where excavating machinery, steam and

electrically powered navvies, and conveyors were made.

Fencing, for fences, gates, railings, balustrades, signs,

etc.

Motor

Frames which produced chassis and pressed steel parts for

motor cars.

Roofing where steel roofs, railway station buildings,

railway bridges, aeroplane sheds, and buildings for all kinds of

industrial uses were produced.

The business had greatly expanded since the

early days, and so Alfred Owen now had to manage the business as

a whole, rather than look after the day-to-day management of the

individual departments. He also had his other business interests

to consider, having invested in other companies. He set-up a

staff council consisting of the various departmental heads, with

himself as Chairman. The members were:

Charles Guy (Roofing), Henry

S. Price (Engineering), William Slater (Fencing),

William S. Stambridge appointed in October 1913

(Aviation), and Albert Wilkes (Motor Frames). |

|

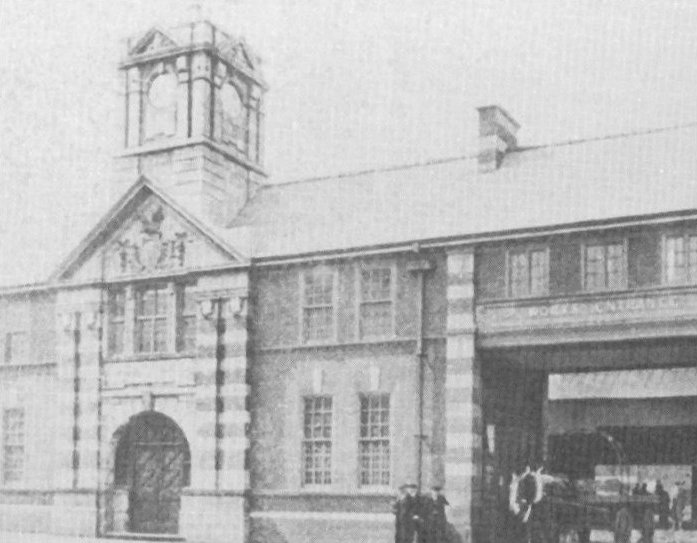

The new offices. From a 1914

letterhead. |

Also in 1912, new offices were opened, with a

canteen and Works Institute, and also a new factory entrance,

complete with clock tower.

A recreation ground also opened on

a nearby piece of land, with bowling greens and tennis

courts to provide relaxation and

enjoyment for the workers at midday or in the evening. |

|

The

institute included a billiards room, a reading room and a

concert room, which were greatly appreciated by the employees.

By 1914 the firm's main products

were:

| Structural steelwork,

bridges, buildings, roofs, tanks, girders, etc. |

| Excavating and conveying machinery,

steam and electrically driven navvies. |

| Water purification plants,

bacterial treatment for town supplies, filtration and softening

for industrial purposes. |

| Electric steel castings. |

| Fencing and gates

(ornamental and plain),

tree guards, garden seats, etc. |

| Black washers and light presswork. |

Motor car and wagon frames

(hydraulically pressed and rolled channel),

hydraulically pressed axle casings,

brake drums, clutch drums, etc. |

| Aeroplane framework,

engine housings, cold drawn steel tubing, tighteners, eye bolts,

and all accessories. |

During the First World War

manufacturers were required to concentrate on the war

effort by fulfilling ministry contracts. Rubery Owen was

in a unique position, being the only firm capable of

producing large quantities of small aircraft parts for the Government.

|

The Rubery Owen office building in 2014.

The Offices in 1920.

A letterhead from 1914.

| At the end of hostilities, the wartime ministry

contracts were terminated and the factory returned to

normality. In April 1919 the staff council, which was

set up seven years earlier became the Committee of

Management. In the same year the firm built a very large

steam excavator, designed by A. R. Grossmith for J. B.

Forder & Son's Pillange Brickworks, and the Engineering

Department was sold to the Wellman, Smith, Owen

Engineering Corporation. On Saturday 16th August, 1919 a

new Canteen and Works Institute opened on part of the

original recreation ground. |

|

|

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Expansion |

|