|

|

|

In the 1950s, most men in industrial

areas worked in factories. The older members of the

workforce would have started work at the age of 13, and

spent most of their life working at least a forty hour, five

day week, often plus Saturday mornings. After such a life,

retirement often came as a shock, and some people found it

difficult to adjust to a life of leisure.

The 1946 National Insurance Act

introduced a contributory state pension for all, which was

paid to men from the age of 65, and to women from the age of

60. The scheme began to operate in 1948. Although many

employers insisted that staff had to leave when reaching

retirement age, this was not the case at Rubery Owen, where

older workers were well looked after. Many chose not to

retire at retirement age, but continued doing their job as

long as they could. Some jobs required hard physical effort,

and so were unsuitable for the elderly. Wherever possible

the company found them lighter work, so that they could

continue at the factory, until old age took its toll.

Most industrial towns had a Sons of

Rest, where retired male workers could socialise, and pass

time away. Each had its own small community who met for a

cup of tea and a chat, or to play a game of cards, dominoes,

or darts, and occasionally go out on day trips to places of

interest.

Sir Alfred Owen was president of the

Sons of Rest in Darlaston and felt that it was not really

meeting the needs of the elderly. While at work, he was

presented with a list of the over 70s at the factory, and

asked what was to be done with them. There were not enough

light jobs available, and they could not cope with the high

physical demands, and the speed of operation in the

workshops.

He came up with a novel idea, a sons of

rest workshop, where members could work at a slower pace

than in the factory, carrying out light work, which would

give them a sense of purpose, and the satisfaction of a job

well done. They would also receive a small wage which would

supplement their pension.

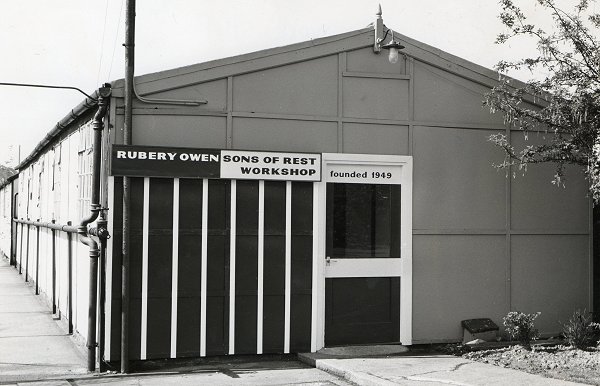

Two wooden buildings were erected end-to-end in a corner

of the 14 acre Rubery Owen sports ground at Bentley. Each

building was 60 ft. long by 20 ft. wide. Initially the

interior consisted of a small workshop and a larger rest

room, with games, tables and armchairs. As the project

progressed, the rest room was made smaller, and the workshop

enlarged. There was a maximum of twenty two members, who

were known as ‘sons’, a foreman, and a warden. The first

foreman, Sam Checketts had originally been a superintendent

in the factory, but because of his age, had moved to a

lighter job in the tool room. The first warden, 75 years old

E. Fraser-Ryder had previously been the senior sports

organiser, before which he was a headmaster, and an

all-round sportsman. |

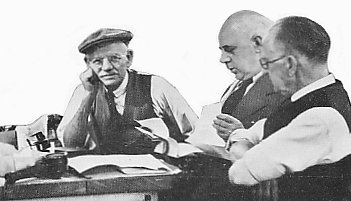

The official opening of the Sons

of Rest workshop in August, 1949. In the centre is Mr.

A. G. B. Owen, Mr. John Beddows, and Mr. Harmer

Nicholls, Chairman of Darlaston Urban District Council.

From the autumn 1949 edition of 'Goodwill' the Owen

Organisation's staff magazine. |

|

The Sons of Rest was officially opened

in August 1949 by Mr. Harmer Nicholls, the Chairman of

Darlaston Urban District Council. On Thursday 8th September

the BBC arrived with a recording van, and Leslie Cargill of

the Midland Region interviewed some of the sons. The new

establishment was expected to pay its way by obtaining

outside orders for short runs of metal objects, and by

supplying the company with much needed small and awkward

parts.

The eldest of the first group of sons

was 82 years old John Beddows who had worked for many years

in the main factory. Other members of the sons included 72

years old Bill Critch, who had worked in the structural

engineering division for forty five years, and 72 years old

Caleb Ludford, who had worked for nineteen years as a

skilled jig-maker. Then there was Elijah Bradley, also 72,

who had twenty three years service, Sam Checketts, again 72,

with seventeen years service, 71 years old Charlie

Griffiths, and Sidney Trow, and Bill Eaton, both 70. |

|

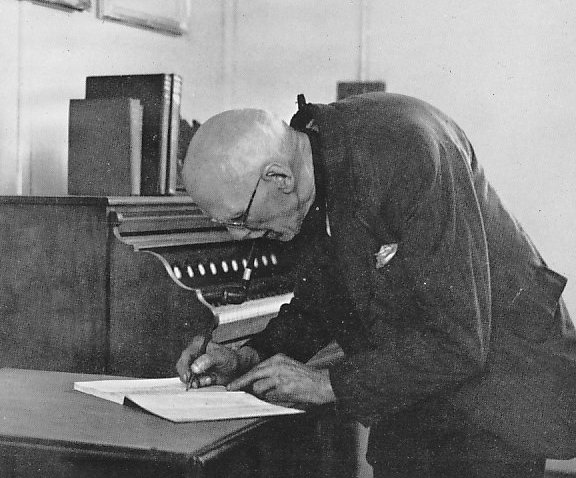

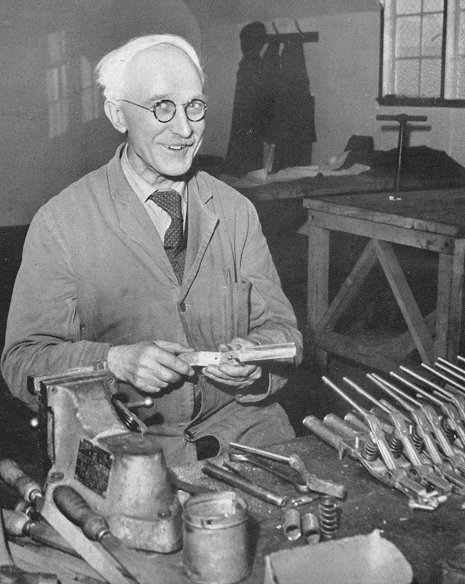

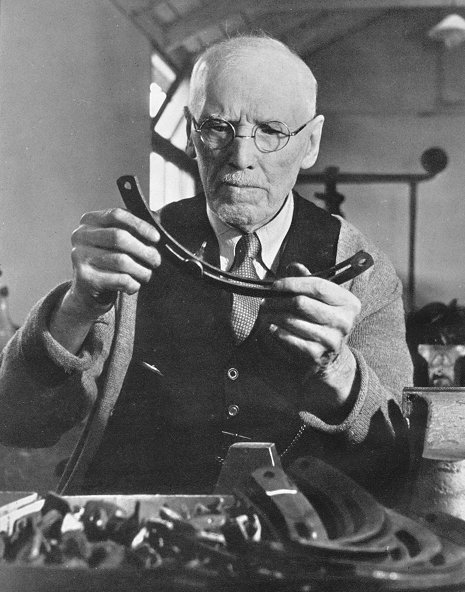

John Beddows at work in the

factory, doing a hard physical job that was not really

suitable for someone of advanced years.

From the Christmas 1949 edition of

'Goodwill' the Owen Organisation's staff magazine. |

| John Beddows signs in at the start

of a day at the sons workshop, full of enthusiasm, and eager

anticipation of the day ahead.

From the Christmas 1949 edition of

'Goodwill'. |

|

|

Mr. A. G. B. Owen chatting to

Enoch Ratcliffe in the rest room.

Enoch was an ex-works policeman. |

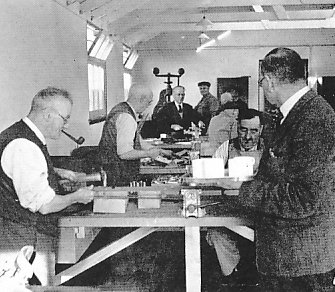

| A group of the sons.

Back row left to right: Jack Pursalt,

Bill Critch, Bill Cox, and Bob Tilley.

Middle row left to right: Charlie

Griffiths, Frank Dark, Harry Taylor, and John P. Rainsbury.

Front row left to right: Joe Baker,

E. Fraser-Ryder, and Sam Checketts. |

|

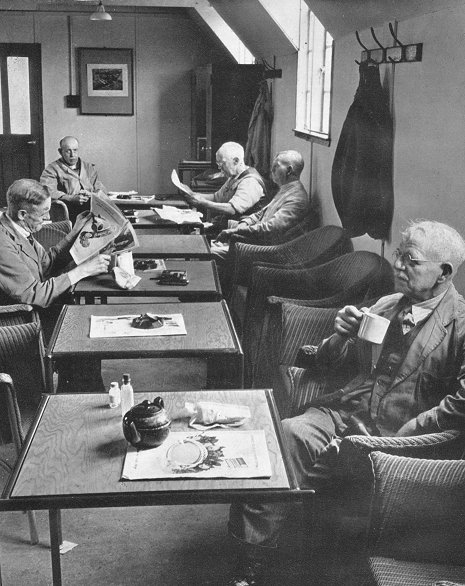

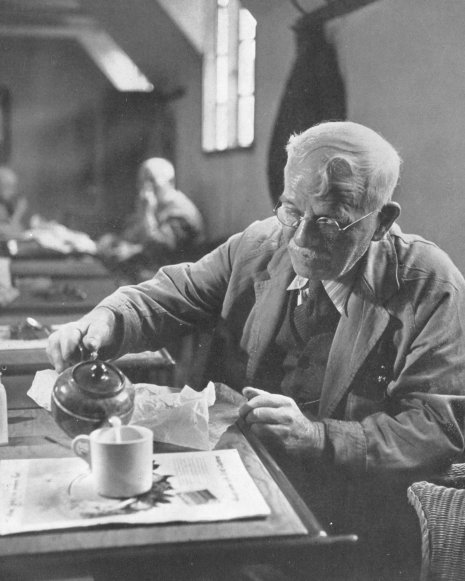

Tea time in the workshop. Twice a day

the warden, Mr. E. Fraser-Ryder came round with

refreshments. From the Christmas 1949 edition of 'Goodwill'. |

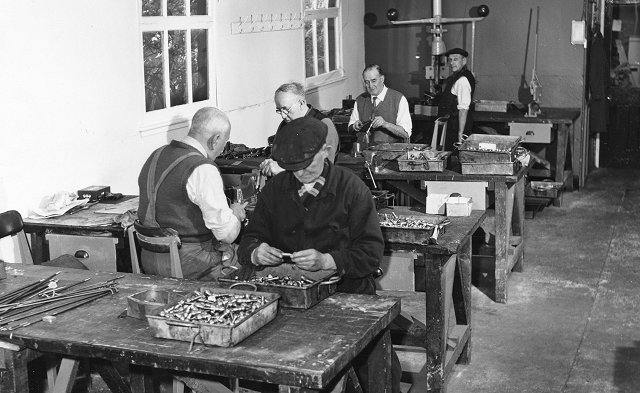

The sons were all skilled men, with vast experience and

expertise, in widely different areas of production. There

was a prevailing feeling of belonging amongst the sons. They

greatly enjoyed their time in the workshop, and were always

bubbling with enthusiasm, contentment and happiness.

Something that was rarely found in the factory.

They were extremely conscientious, and ensured that

anything produced in the workshop would be made to the

highest standards, which helped to assure the profitability

of the project.

The sons were never late, and couldn’t wait to start work

at the beginning of each day. Theirs was close-knit

community in which they eagerly undertook the most menial of

tasks. One of the sons spent most of his time in the

workshop carrying out assembly work and filing. The

remainder of his day involved scrubbing and cleaning the

floors, dusting and polishing the furniture, and cleaning

the windows. |

| One of the sons carried out precision drilling, another

was an assembler and cold riveter. Another had learned to

operate an electric sewing machine, and spent his time

producing many types of industrial protective clothing, jeep

hoods, and car seat covers. Another of the sons, the

workshop manager, produced the technical drawings, and

helped to find the outside orders that funded the project.

The sons greatly enjoyed the challenge of producing a

prototype, and ironing out any problems. |

Mr. A. G. B. Owen giving his opening

address in the rest room. From the autumn 1949 edition of

'Goodwill'. |

|

One of the sons hard at work on

the sewing machine. Courtesy

of Tony Highfield. |

|

Bill Cox on the sewing machine. |

|

|

Frank Dark making cable clips. |

|

Lunchtime in the rest room. |

|

|

An enjoyable lunchtime chat. |

|

A welcome cup of tea. |

|

A busy day in the workshop. Courtesy of Tony

Highfield.

|

The other half of the workshop.

Courtesy of Tony Highfield. |

| Some of the varied

tasks that were carried out daily, from the filing of small

components to cutting timber.

Courtesy of Tony Highfield.

|

|

|

Two of the drilling machines in

operation. Courtesy of Tony

Highfield. |

| Filing and assembling small

components. Courtesy of Tony

Highfield. |

|

Sam Checketts (left) being interviewed

by Leslie Cargill the BBC commentator. From the autumn 1949

edition of 'Goodwill'. |

All kinds of articles were made in the workshop

including jigs, tools, and fixtures, all demanding a high

degree of skill and craftsmanship. Items were fabricated in

metal, wood, and plastic.

Products included small items such as heavy duty

electrode holders, and earth clamps. Larger items included

tubular steel hammock beds for nurseries, and two hundred

agricultural seeding units, each 8 ft. 6 inches long, and

weighing 2¾ cwts. They were built at a competitive price, on

a strict monthly delivery schedule. |

|

Carefully drilling a hole. |

|

|

John Beddows inspects a newly-made

component. |

| The sons’ lunch break began at 12 o’clock. They would

settle down to a sandwich and a cup of tea, followed by

reading a newspaper, a game of darts, or cards, or maybe a

snooze. There was often little conversation.

At 12.55 p.m. they would promptly finish what they were

doing in order to return to their bench or machine by 1

o’clock sharp. |

Leslie Cargill interviewing some of

the sons in the workshop. From

the autumn 1949 edition of 'Goodwill'. |

|

The sons’ social activities were

limited to a day’s outing in the summer, and a lunch and tea

at Christmas. It was paid-for from the profits of the rest

room, a donation from the three managing directors, and a

weekly subscription, to which each son contributed. The rest

room profits came from the daily two cups of tea, costing

one penny each, which were prepared and served by the

warden.

Sir Alfred Owen was a deeply religious

man. Every Good Friday, the sons were expected to join him

at a morning service. They rarely saw the managing directors

at other times, other than the Christmas tea party, which

they always attended. |

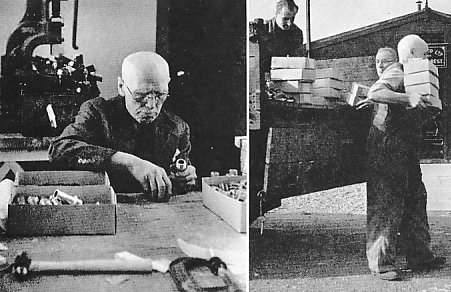

John Beddows at work in the workshop,

and carrying boxes containing components from the main

factory, that had to be finished off. From the Christmas

1949 edition of 'Goodwill'. |

They had a steady stream of visitors,

who inspected the sons’ daily routine with interest.

Initially the scheme attracted a lot of publicity and so

callers arrived from various newspapers and publications.

When this activity died down, representatives from other

manufacturing companies, from much of the world, came to

evaluate the scheme, and consider the possibility of

setting-up their own sons of rest workshop.

Visitors were always well looked after,

and numerous names appeared in the visitors’ book. A regular

visitor was the group chaplain. He used to sit in the quiet

rest room to answer his correspondence. |

|

Bob Tilley at work. |

|

|

Charlie Griffiths and Sam

Checketts. |

| The sons of rest workshop was a great success. It added

a sense of purpose to the lives of the sons, and kept them

active in both mind and body.

It equally served the factory well, providing small

components that were essential, but difficult to make. |

Home time, after a rewarding day. From

the Christmas 1949 edition of 'Goodwill'. |

|

A later view of the workshop.

Courtesy of Tony Highfield. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to The

Later Years |

|

Return to the contents |

|

Proceed to

Sports & Leisure |

|