|

Countries with Owen Group Agents,

in the 1950s. |

Mrs. Eccleston on her drilling machine

in the Aviation Department. From the spring 1950 edition of

the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

The 1950s and 1960s were years of significant and sustained

growth for the company. In 1951, A. G. B. Owen set up the Owen

Organisation so that a clear distinction could be made between

the Owen Family's ownership of Rubery, Owen & Company Limited

and their other investments.

At that time the Owen Organisation

consisted of twenty eight member companies, employing over

12,000 people in operations as diverse as aerospace,

agricultural implements, and automotive components, chains,

domestic equipment, fork lift trucks, office furniture, nuts and

bolts, and tools. The firm also became involved in motor racing,

as a result of A. G. B. Owen's interest in the sport. |

| B.R.M. British Racing Motors (BRM)

became synonymous with the Owen Organisation which sponsored the

racing team for many years. The project, founded by racing

enthusiast Raymond Mays, and his associate Peter Berthon began

in 1945. |

| Mays and Berthon, along with Humphrey Cook had

previously built a number of successful racing cars using the

ERA name. Mays wanted to build an all British grand prix car to

fly the flag for British engineering.

He intended to fund the

project by seeking financial backing from the British motor

industry and established the British Racing Motor Trust. A. G.

B. Owen became chairman of the trust, and decided that the Owen

Organisation should take over the assets of the trust when it

ran short of funds.

The assets were purchased on 24th October,

1952 so that development work on the existing cars could

continue, and also with the aim of designing and building a 2.5

litre un-supercharged car in readiness for the 1954 racing

season. |

The BRM logo. |

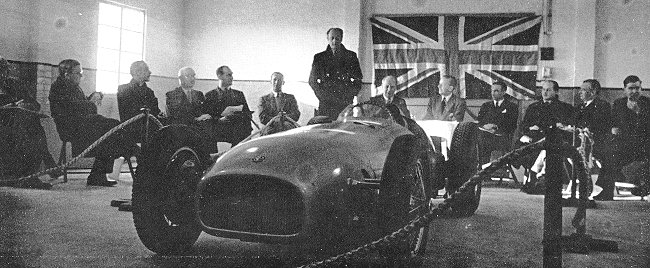

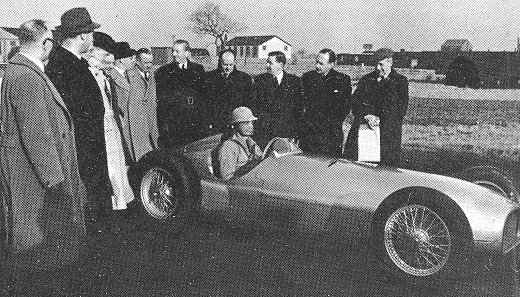

The first BRM is unveiled at

Folkingham. Left to Right: H. Bailey (M. of S.), L. H.

Robinson (M. of S.), R. Henderson-Tate (North Midland

Regional Controller of M. of S.), A. C. Burdon

(Automotive Products), A. G. B. Owen, D. G. Flather (W.

T. Flather & Co. Ltd.), Raymond Mays, Earl Howe, Donald

McCullough, the Duke of Richmond and Gordon, Peter

Berthon, Wilfrid Andrews (RAC), and B. F. W. Scott

(Joseph Lucas Ltd.) From the spring 1950 edition of the

staff magazine "Goodwill". |

The cars were built in a building called 'The Maltings', in

Spalding Road, Bourne, Lincolnshire, behind Mays' family home,

called 'Eastgate House'. When the Owen Organisation took control

'The Maltings' became the Engine Development Division of the

Owen Motor Racing Association. Berthon and Mays continued to run the team on

behalf of the Owen Organisation, and had many racing successes

including winning seventeen grand prix between 1959 and 1972:

|

Date |

Race |

Driver |

| 31st May, 1959 |

Dutch Grand Prix. Zandvoort |

Jo Bonnier |

| 20th May, 1962 |

Dutch Grand Prix. Zandvoort |

Graham Hill |

| 5th August, 1962 |

German Grand Prix. Nürburgring |

Graham

Hill |

| 16th September, 1962 |

Italian Grand Prix. Monza |

Graham Hill |

| 29th December, 1962 |

South African Grand Prix. Prince

George |

Graham Hill |

| 26th May, 1963 |

Monaco Grand Prix. Monaco |

Graham Hill |

| 6th October, 1963 |

United States Grand Prix.

Watkins Glen |

Graham Hill |

| 10th May, 1964 |

Monaco Grand Prix. Monaco |

Graham Hill |

| 4th October, 1964 |

United States Grand Prix.

Watkins Glen |

Graham Hill |

| 30th May, 1965 |

Monaco Grand Prix. Monaco |

Graham Hill |

| 12th September, 1965 |

Italian Grand Prix. Monza |

Jackie Stewart |

| 3rd October, 1965 |

United States Grand Prix.

Watkins Glen |

Graham Hill |

| 22nd May, 1966 |

Monaco Grand Prix. Monaco |

Jackie Stewart |

| 7th June, 1970 |

Belgian Grand Prix. Spa |

Pedro Rodríguez |

| 15th August, 1971 |

Austrian Grand Prix. Österreichring

|

Jo Siffert |

| 5th September, 1971 |

Italian Grand Prix. Monza |

Peter Gethin |

| 14th May, 1972 |

Monaco Grand Prix. Monaco |

Jean-Pierre Beltoise |

Other team drivers included Ron Flockhart, Dan Gurney, Mike

Hawthorn, Niki Lauda, Reg Parnell, Clay Regazzoni, Harry Schell,

John Surtees, and Maurice Trintignant. In 1962 Graham Hill

became world champion. |

|

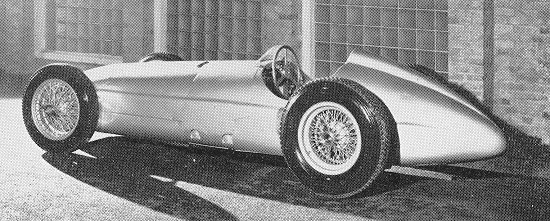

The finished car standing outside

the test house at Bourne.

It had a top speed of around

200 mph.

From the spring 1950 edition of the

staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| As well as providing financial support, the Owen

Organisation also placed its vast manufacturing resources at

the disposal of the project. Large numbers of specialised

components were produced at some of the factories within the

organisation. Chassis were built at Darlaston, along with

the majority of bolts, nuts and studs, which were often made

from special steels. Electro-Hydraulics did much precision machining, Invicta

Electrodes assisted with electrodes and welding techniques, Camelinat produced spinnings,

pressings and bushes, C. & L. Hill supplied light alloy

castings, and Motor Panels made the water inlet manifolds,

radial arms and engine bearer struts. The organisation also

supplied the necessary jigs, tools, fixtures, drills,

reamers, and cutters, etc., and also machinery, office

furniture, and storage units for the Bourne site. |

| The Bourne technicians and

designers who made it possible, including Peter Berthon, Ken

Richardson, and the three principal members of the design

team: Frank May (Chief of the Design Office), Harry Mundy,

and Eric Richter. From the

spring 1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

|

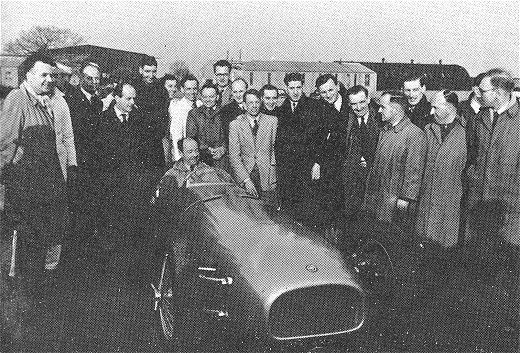

The beginning of the first car's

trial run. From the spring

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| In order to try and make the Owen Motor Racing

Association pay its way, the BRM V8 engine was sold to other

racing car builders. In 1960 the workshop moved to a new

purpose-built building on an adjacent site, previously

occupied by Bourne Gasworks. In the 1960s, Louis Stanley, A.

G. B. Owen's brother-in-law, became involved with BRM,

ending up as Joint Managing Director, and later Chairman.

The Owen Organisation ended its support for the team in

about 1970, after which it became Stanley-BRM, and remained

as such until 1977. |

|

|

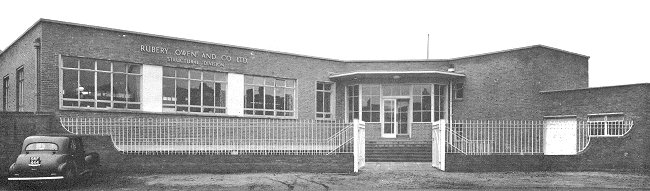

The new Structural Division Office

Building. From the spring

1951 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| The Structural Division Office in the Central Office

block was some distance away from the Structural Works, and

so a new office was built next to the factory, and partly

over the Template Shop. It had a waiting room, cloakrooms, a

Manager's Office, a Drawing Office, an Estimating Office,

and a General Office. |

|

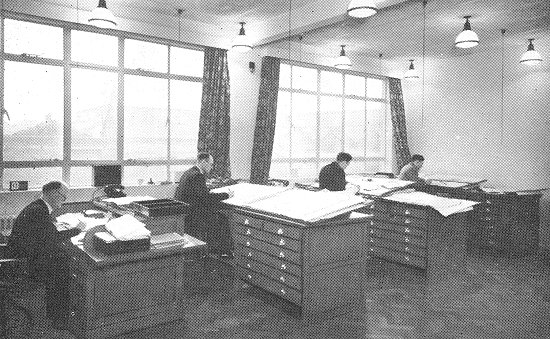

The Drawing Office.

From the spring

1951 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| The Estimating Office.

From the spring

1951 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

|

The Ferguson plough. Made at the

Darlaston factory.

From the spring

1951 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| In 1953 the Owen Organisation acquired Charles Clark and Son Limited of

Wolverhampton, which sold cars. |

| In 1956 the Darlaston factory was restructured into

seven divisions, each responsible for the design and sales

of its products: Motor Division produced car

components, chassis frames, presswork, wheels, axle cases

and fuel tanks.

Structural Division designed and produced

steelwork for buildings.

Contracts Division manufactured earthmoving

equipment and cranes for sub-contract.

Bolt and Nut Division produced bright bolts and

nuts for the motor industry.

Metal Assemblies Division carried out deep-drawn

presswork, particularly for vehicle brake cylinders,

compressor shells for refrigerators, washing machines, gas

bottles and cylinders etc.

Metal Equipment Division produced steel shelving,

pallets and containers.

Rowen-Arc Division produced welding machinery. |

A 1920s view of Charles Clark & Son

Limited, Chapel Ash, Wolverhampton. From an old postcard. |

| Some parts of the business were still centrally

controlled under the Central Services Division, which

offered assistance to subsidiaries, and charged for the

services provided, including finance, purchasing, research,

personnel, and engineering plant and maintenance services.

Some of the organisation's specialist factories, like

Pressings in Coventry, Foundry Equipment in Shropshire, and

Industrial Storage and Office Equipment at Wrexham, were

also managed from Darlaston. At the time there were 6,000

employees at the Darlaston site. The organisation had also

opened a pioneering scheme to look after the older members

of the workforce, as their working lives drew to a close.

|

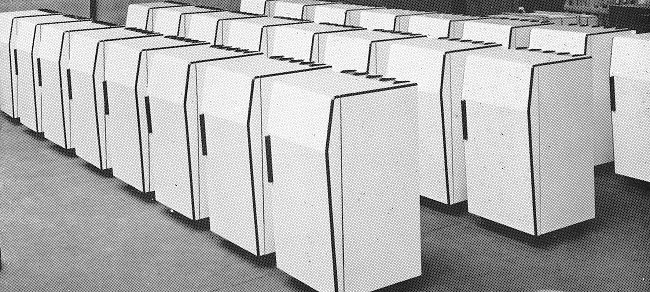

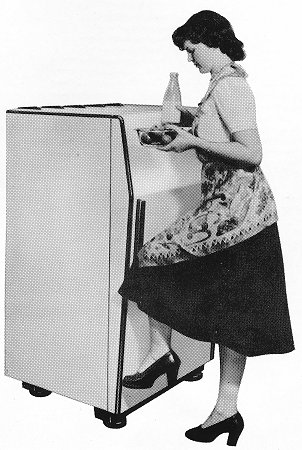

Finished refrigerators at the

factory. From the summer

1950 edition of "Goodwill". |

From the summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

One of the many products made in

the Darlaston factory was the 'Gasel ' absorption type

refrigerator, which was completely silent in use, and

fully equipped with automatic controls. It could be run

on gas, kerosene or electricity, and had no electric

motor, or belts, and so was extremely reliable, and

long-lasting.

It used a small gas or kerosene

flame, or an electric element, to evaporate a liquid

refrigerant, which extracted heat from the refrigerator.

The cabinet was styled for Gasel

Appliances Limited by Grey Wornum, F.I.R.B.A., a

well-known British architect, and had a door that could

be opened or closed by a feather touch from an elbow or

knee, when the hands were full.

It was finished in stove-enamelled

white gloss paint with a plastic trim. The cabinet was

manufactured by the Metal Equipment Department, and the

white porcelain-enamel interior was finished at the

vitreous enamelling plant. |

| Forming the interior casing on

a brake press. From the

summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

|

Making the streamlined doors

and panels. From the

summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| Seam welding the interior

sections. From the summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

|

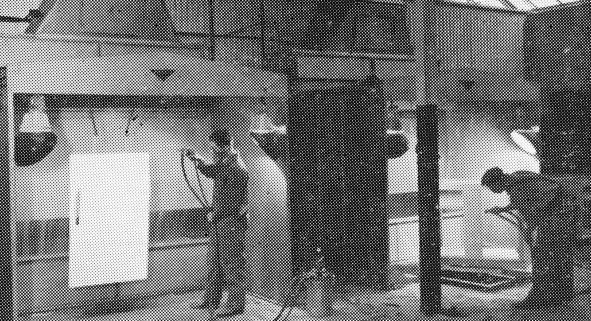

Spray enamelling the doors,

prior to baking. From the

summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

| Fitting the absorption unit

into a refrigerator. From

the summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

|

|

The final inspection.

From the summer

1950 edition of the staff magazine "Goodwill". |

On 21st November, 1962 the company was honoured by

a Royal visit to the Darlaston factory, by Princess

Margaret, who toured the Motor Wheel Department, the service

departments, the Nursery, and met the medical personnel.

|

|

|

|

|

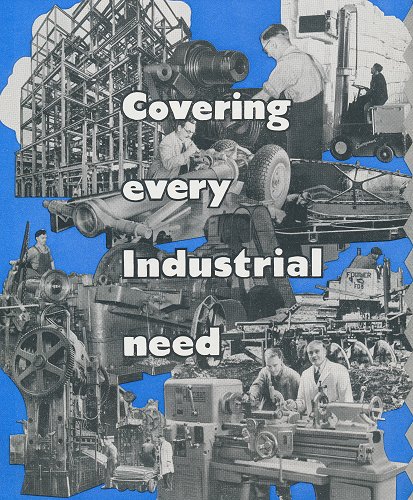

An advert from 1952. |

|

An advert from 1938. |

|

| The Next Generation

In the 1950s and 1960s the third generation of the Owen

family began their careers with the company, starting with

A. G. B. Owen's eldest child, Helen Grace Owen who

joined the firm in 1952. After obtaining her degree at

Birmingham University, she worked in Head Office until her

marriage. She was responsible for office development, and

was involved in the firm's preparation for retirement

programme, and also introduced industrial life and Christian

teamwork into the workplace.

A. G. B. Owen's two eldest sons joined the company after

graduating in economics at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Alfred David Owen

started in the Motor Division in 1961, after completing his National

Service. In 1963 he became its General Manager in 1963. John Ernest Owen

spent a year at Jaguar Cars Limited,

as a management trainee before becoming Managing Director of the Easiclene company

in 1963.

A. G. B. Owen's younger children also joined the firm.

Jean Elizabeth Owen began as her father's secretary in 1961

before joining the Estates Department in 1966, where she was

involved in the development of the organisation's

camping and chalet leisure

site at Dyffryn in Wales. She later became a director of

Chains Limited, and oversaw her father's interests in New

Hall Farms Limited, and the Park House Restaurant in Sutton

Coldfield.

|

| The next youngest son, Robert James Owen, joined the firm

in 1967. After completing his HND in business studies, he

worked in the Training department.

Another son, Charles Owen

joined the firm in 1976 after becoming a chartered

accountant. In 1978 he became a Director of Rubery Owen

(Metal Assemblies) Limited, and a year later became Managing

Director.

By 1963 there were more than 50 companies in the

organisation, producing many new products including Drott mobile tractor cranes,

and self-propelled straddle lifting systems.

In 1964 there were 6,500 employees on the Darlaston site,

and the firm took over Old Park Works on King's Hill,

Wednesbury, which then became Rubery Owen Kings Hill Works.

|

An advert from 1954. |

|

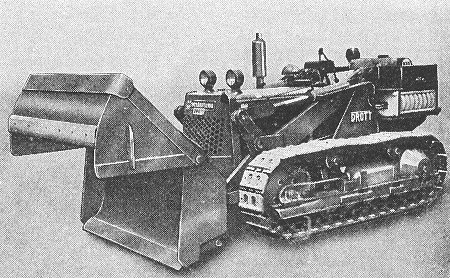

A Drott mobile tractor fitted with

a skid shovel. From Histories

of Famous Firms - 'Midlands Survey' part one, 1960. |

| Also in 1964, a Rubery Owen-built vehicle became the

fastest car on earth, reaching a speed of 403.1 mph. Donald

Campbell desperately wanted to hold the world land speed

record, to showcase British engineering skill. This was made

possible thanks to many British companies in the motor

industry who supplied parts and expertise, and the Norris

brothers who designed the car, known as Bluebird CN7. The

original CN7 led to many disappointments. In 1960, after

initial trials, the car was taken to the Bonneville Salt

Flats in Utah, USA, but whilst travelling at over 360 mph

Campbell lost control and crashed. He was badly injured, and

the car was written-off. |

|

An advert from 1958. |

Campbell still wanted to make another attempt at the

record, and so Sir Alfred Owen offered to rebuild the car,

which had been built by the Owen Organisation, for him.

By

the summer of 1962 the

rebuilt car was ready, and by the end

of that year Campbell had shipped it out to Lake Eyre in

Australia in readiness for a new attempt on the record.

Unfortunately nothing could be done for some time because of

rain, which flooded the course. On 17th July, 1964 Campbell

made another attempt, even though the course had still not

properly dried out. This time he achieved his goal,

travelling over the course at an average speed of 403.1 mph,

which was a great triumph for the many Owen companies

involved in the project.

Sadly, overwork and advancing years were beginning to

take their toll on Sir Alfred Owen. At the end of 1964 he

collapsed whilst on a visit to South Africa, and so

delegated some of his workload to his eldest sons, David and

John, who became joint chairmen of the newly formed Group Executive. |

| In the late 1960s many changes took place in the

management of the business. In 1966 Rubery Owen & Company Limited

became a holding company under the name of Rubery Owen

Holdings Limited, whose role was to oversee the activities of the

group. The assets and activities of the Darlaston

factory and its subsidiaries came under the control of a

new company, also called Rubery Owen & Company Limited,

which must have caused a great deal of confusion.

Possibly because of this, the name was soon changed to Rubery

Owen (Darlaston) Limited. David and John Owen became

directors of the new company. David was Chairman, and

John looked after the Domestic Equipment Division. After

the death of his uncle, Ernest William Beech Owen in

February 1967, John also looked after the Contracts and

Agricultural Divisions, and in March 1967 the brothers

became Joint Managing Directors. For a time the

organisation suffered from a cash problem because Ernest

William Beech Owen had owned one third of the shares.

Two years later, Sir Alfred Owen suffered a serious

stroke, and relinquished most of his duties,

although he remained Chairman of the company until his death on 29th October, 1975.

The day-to-day management of the firm was then left to

the two brothers, with David becoming Acting Chairman,

and manager of the subsidiary UK and overseas companies,

and John becoming Managing Director of the Darlaston

factory, and its associated companies in Moxley, Wrexham

and Warrington. |

|

| As part of the reorganisation, the Structural

Fabrications Department at Darlaston closed. The Organisation had

great difficulty in raising capital in order to expand the

business. Electro-Hydraulics Limited, based at Warrington,

became a public company with 40% of its shares offered for sale. The

shares sold quickly and allowed the firm to reorganise, and reduce its overdraft.

In the late 1960s the extensive product range

included automated warehousing, earthmovers, farm

equipment, foundry and welding plant, fuel pumps,

integrated handling systems, machine tools, yachts and

boats, and much more. The group produced around 12,000

different components, assemblies and machines on a

worldwide basis, employing more than 15,000 people in

eighty eight companies, operating on five continents.

The Life of Alfred George

Beech Owen

A. G. B. Owen was born on 8th April, 1908, and

educated at Lickey Hills School, followed by Oundle

School in Northamptonshire. In 1927 he went to study

engineering at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, but

abandoned the course on the death of his father,

Alfred Ernest Owen, who died on 29th December, 1929,

in his sixtieth year.

A. G. B. immediately took control of the family

business with his younger brother, Ernest William

Beech Owen, and in 1932 married Viva McMullan. They

had five children. In 1934 he was elected to

Darlaston Urban District Council, and became

Chairman in 1942 to 1946 and 1952 to 1954. He also

became a member of Sutton Coldfield Council in 1937,

which is where he lived with his family. He became

Mayor of Sutton Coldfield in 1951, and in 1970 was

made the last Freeman of the Borough.

From 1949 until 1966 he was a member of

Staffordshire County Council, and held the post of

Chairman between 1955 and 1962. He was also Chairman

of Dr. Barnardo's for 22 years, Pro Chancellor of

Keele University, Vice Chairman of the National

Savings Movement, Deputy Chairman of the Development

Corporation for Wales, Chairman of Governors for

Bishop Vesey's Grammar School, President of St.

John's Ambulance for Staffordshire, Director of

Walsall Football Club, and Chairman of the National

Road Safety Advisory Committee.

In Darlaston he was President of the Old People's

Welfare Committee, President of the Sons of Rest,

President of the Darlaston and District Social

Services, President of the Garden and Allotments

Association, and President of the Fellowship for the

Disabled.

In March 1954 he was awarded a CBE, and in 1961 received a Knighthood for public service. Because of his involvement in the various

organisations he worked an average of 18 hours a

day, and drove up to 50,000 miles a year.

In October 1969 he suffered a serious stroke from

which he never fully recovered. At the time he was

waiting to preach in St. Matthew's Church, Walsall.

He died on 29th October, 1975. |

|

Sir Alfred in his

private room in the Walsall General Hospital

after his stroke. On the right is Sister Irene

O'Malley. From

Owen News. |

Sir Alfred (centre) at a

retirement presentation at Waddington Tools on 20th

October, 1971.

|

The 1970s

In 1970 the main subsidiary companies in the group

were reorganised into sub-groups, each under the control

of a holding company. The holding companies were as

follows:

| The C.&L. Hill Group,

The Conveyancer Group, The Distributors Group,

The Domestic Equipment Group, |

| The Fasteners Group,

and Rubery Owen (Darlaston) Limited which

was also administered as a separate |

| sub-group. |

By 1971 there were around 14,200 employees in the

group, and the group's profits slightly improved. |

A presentation in the central

toolroom for the Motor Frame Department in about

1970. Jack Morris (on the left) is being presented

with his retirement present, a set of Gilbert and

Sullivan records, by Jack Price, the Toolroom

Manager. 2nd on the left is Brian Austin, 8th on the

left is Jack Siviter, and 10th on the left is Bob

Taylor. On the right of Jack Price is Doug Russell,

a Foreman, and next right at the front is Harry

Wells the Jig Maker Foreman. In the centre on the

front row, wearing glasses is Benny Fellows, 5th

from the right on the front row is Ernie Horton, 5th

from the right on the back row is Charlie Wood, and

in front of him to the left is Eric Frankham.

Courtesy of Brian Austin. |

| The next decade was a trying time for the company,

and the country as a whole. I have included a brief

description of the terrible times which led to the

demise of much of the country's industry, and explains

the extreme measures that had to be taken by the

Owen group in order for some parts to survive. |

|

From a 1954 advert. |

The

late 1960s and the 1970s were turbulent times for

British industry, the economy was in decline and trade

unions began numerous strikes which worsened the

situation.

At first the future must have looked extremely bright

for the Owen group, because in the 1960s and early

1970s, Britain enthusiastically embraced the motor car.

There was a rapid rise in the ownership of cars, but

this was short-lived because of the 1973 oil crisis

which saw the price of petrol more than double. The

miners went on strike and were joined by sympathetic

trade unionists. Arthur Scargill led the miners who used

flying pickets to successfully block coal and coke

supplies. The country was short of energy, inflation

accelerated to over twenty percent, and Britain was put

on a three day working week. |

| Industrial relations at Darlaston became strained in

1973 when over 2,000 employees in the Owen Group went on

strike for five weeks. The strike nearly crippled

British vehicle manufacturing, because the company

supplied wheels and components to most of the leading

manufacturers. After the strike, the directors decided

to restructure the company by creating subsidiary

companies.

But deteriorating markets, and the unwillingness of

trade unions to accept changing economic conditions

forced further radical changes. The country's problems increased due to rising prices, falling

industrial output, and the largest number of unemployed

since the recession in the 1930s. In 1974 the industrial

unrest seemed to ease as a result of the Social

Contract, instigated by the Labour Government under

Harold Wilson, along with a strong budget to curb

inflation. Unfortunately this was short-lived. In 1976

the country had to apply for an IMF bailout of £2.3bn,

due to the high budget deficit and the falling value of

the Pound.

By 1977, the economy showed signs of

recovery, but unemployment continued to rise, so much so

that by 1978 around 1.5 million people were out of work.

The winter of 1978 to 1979 became known as 'The Winter

of Discontent' because of widespread strikes by public

sector trade unions, all demanding larger pay rises. It

was also the coldest winter since 1962 to 1963, which

reduced retail spending, and worsened the economy. The

Labour Government's inability to curb the strikes led to

the election of Margaret Thatcher's Conservative

Government in 1979, who legislated to reduce the power

of the trade unions.

The UK economy had fundamental problems that could

only be resolved by a radical shake-up, but sadly by

this time, many of the country's industries had gone,

and many more would soon follow. They were unable to

weather the turbulent storm that had overtaken the

country, or compete with the ever growing foreign

competitors who were taking-over their traditional

markets.

Weathering The

Economic Storm

The recession, the difficult industrial relations,

and the decline of many British industries, as already

mentioned, led to a problematic time for the group,

which must have severely tested the management's ability

to keep the business going. |

| In 1972 the firm decided to concentrate on its

manufacturing and engineering activities, and so the

British Leyland distributor, Charles Clark and Son

Limited, of Wolverhampton, and Rogers and Jackson

Limited of Wrexham were sold. Sales continued in 1973,

by which time twenty subsidiaries had gone. The

Darlaston factory was divided into two companies; Rubery

Owen Motor, and Rubery Owen Contracts, and the group acquired

the remaining forty percent of Conveyancer Fork Lift

Trucks Limited, to become the sole owner. In 1974 the

firm became Rubery Owen Conveyancer. |

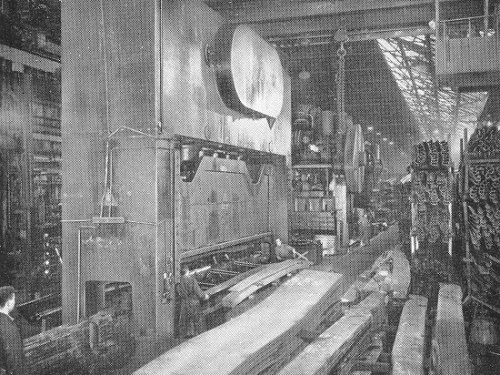

A corner of the Motor Frame Cold

Press Shop at Darlaston. |

| By this time the national industrial unrest was

causing problems, and the Commission on Industrial

Relations made proposals for improving industrial

relations in the company. In 1975 the firm acquired Shelvoke

forklift trucks, and in 1976 the 'Rosafe' wheel for

preventing skidding after a burst tyre, was specially

commended by the Don Trophy scheme. In the same year,

industrial relations at the Darlaston factory plummeted to an all time low, and the factory was

threatened with closure unless things improved. In

1977 Coventry Climax purchased the Conveyancer factories

at Warrington and Kirkby, and by

1978, voluntary redundancy and natural wastage had

resulted in the Darlaston workforce being reduced to

1,650.

|

From the London

Gazette, 22nd August, 1978. |

From the London

Gazette,

7th November, 1978. |

|

In June 1979 the company

shed another 400 employees at the Darlaston factory. In 1981 a

further 950 jobs were lost, followed by the closure of

the Darlaston factory, when the decision was taken to

move away from the traditional manufacturing and

engineering businesses. This was a severe blow to

the town. In the same year the BRM business was

auctioned.

From the London Gazette, 5th June,

1984.

The firm's last major manufacturing interest was

sold in 1993. Rubery Owen Holdings Limited now concentrates on property,

investment, and several independently operating subsidiaries. |

| A sad sight. Part of the derelict

Darlaston factory in the late 1980s shortly before

demolition. |

|

|

Another part of the old

works, sadly now gone. |

| References

An Industrial Commonwealth - 1951. The Owen

Organisation

Copies of the company's staff magazines.

Histories of Famous Firms - Midlands Survey 1960.

Industry in the West Midlands. 1954. West Midland

Industrial Development Association.

There's Life in the Old Dog Yet - 1954. John P.

Rainsbury, Rubery Owen & Co. Ltd.

Access to Archives - www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/

Many adverts from many magazines. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Easiclene |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Sons of Rest |

|