|

Background

It all started in the 1820s when Absolom

Harper and his two sons, John and Edward, founded A. Harper & Sons, ironfounders, at Waddams Pool Works in Hall Street,

Dudley. They specialised in the production of

fenders and fire irons. Absolom’s daughter Mary married George Bean,

a bank clerk who grew-up in Stamford, Lincolnshire,

where he was born in 1855. He met Mary while working

for a bank in Dudley, and soon became financial

manager of Allen, Everitt & Sons of Smethwick. After

their marriage George left his job and joined the

family business. In 1901 he became the principal

shareholder. The name was changed to A. Harper, Sons

& Bean in 1907 when George became chairman. |

|

Drop hammers were installed at the

works in 1911 to produce forgings for the up and coming

motor industry. They were transferred to Smethwick in

1912 when the company established a forging plant there.

It still exists today as Smethwick Drop Forgings

Limited, now a part of GKN. There were 75 drop hammers

varying in size from 3 cwts to 3 tons, capable of

producing forgings up to 1½

cwts.

George Bean became Mayor of Dudley

in 1908, and again in 1911, and 1912. The business

greatly prospered during the First World War thanks to a

plentiful supply of ministry contracts for munitions.

The factory buildings were extended in order to increase

the production of shrapnel and shell cases. By 1916

around 21,000 shell cases were produced every week.

After the war George received a knighthood for his

services to the war effort, and his only son John, known

as Jack, who also worked in the business, was made a

CBE.

The Bean Car

At the end of hostilities the

lucrative munitions orders ceased and something had to

be quickly found to replace them, so that the business

could survive. At the time motor cars were becoming

increasingly popular, and so the decision was taken for

the company to become a car manufacturer.

At this time the jigs, patterns,

tools, and manufacturing rights for the Perry car were

up for sale and so A. Harper, Sons & Bean purchased them

in January 1919 for £15,000 as a way of quickly getting

into the industry by buying a tried and tested design.

The Perry car was made by the Perry

Motor Company at Tyseley, Birmingham. The business was

founded by James and Stephen Perry who made pen nibs in

London before moving to Birmingham to build bicycles. In

the late 1890s their business was purchased by James

William Bayliss, one of the owners of the Bayliss-Thomas

car company. Perry’s first car, the 8hp. Perry 8

cyclecar appeared in 1913 and remained in production

until 1915. It was designed by Cecil Bayliss, son of

James Bayliss. The car had an unusual two cylinder

engine in which both the cylinders rose and fell at the

same time.

About 800 Perry 8s were produced. In 1914

the company launched the Perry 11.9, a full-sized car

powered by a Perry four cylinder 1795c.c. engine.

Production continued until 1916 by which time over 300

had been produced. After the war Perrys decided not to

resume car manufacturing and so the design was put up

for sale. After their purchase, A. Harper,

Sons & Bean decided to manufacture the car and call it

the Bean.

Into Production

Jack Bean the company’s Managing

Director was an extremely ambitious man who planned to

produce vast numbers of the Bean car, to become one of

the country’s leading car manufacturers. With this in

mind he visited America to purchase the latest

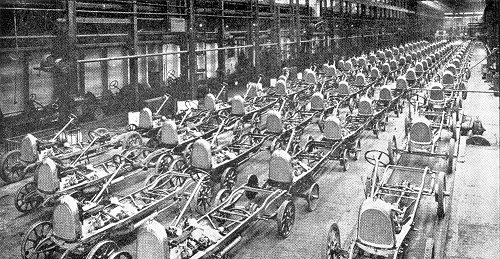

machinery. As a result the company became one of the

first in the country to have twin moving track assembly

lines. |

| Jack envisaged a large organisation

formed from a consortium of manufacturers that between

them could produce maybe 75,000 cars and 25,000 lorries

a year, something like the massive General Motors

combine in America.

He planned to take on the British

built model T Ford. Thanks to his drive and enthusiasm a

group of companies including vehicle maker Swift, car

and lorry maker Vulcan, Hadfield Steel Company of

Sheffield, the Regent Carriage Company, and radiator

makers Alex Mosses, and Gallay came together to Form

Harper Bean Limited in November 1919.

A newly built factory at Tipton began to produce

complete car chassis which were driven

to the Waddams Pool Works in Dudley for the bodies to be fitted. The Smethwick factory would provide all

of the forgings that were necessary.

The body shop at Waddams Pool Works occupied a site

covering 327,000 square feet. It had a capacity of

twenty cars per day.

Departments included the body assembly department,

the paint shop, the sawmill, the trimming shop, the

experimental department, and the cushions and hoods

department.

|

|

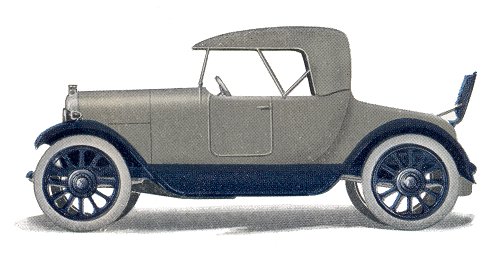

| The company’s first car, the Bean

11.9, a slightly updated Perry design, was launched at

the 1919 Motor Show. The models on display consisted of

a 2 seater tourer priced at £425, a 4 seater tourer

priced at £450, and a complete chassis. The range was

soon augmented by the addition of a 2 seater coupé

priced at £500, and a 4 seater coupé priced at £550.

Harry Radford was employed as Chief Designer to oversee

the initial modifications that were made to the Perry

design, and Tom Conroy an American production engineer

took charge of the Tipton factory. |

|

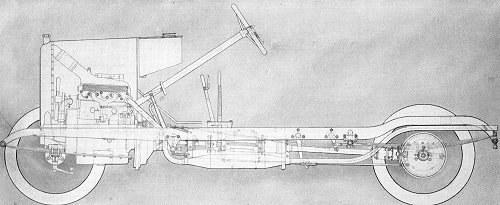

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

The Bean 11.9 chassis that was built at

the Tipton factory. |

|

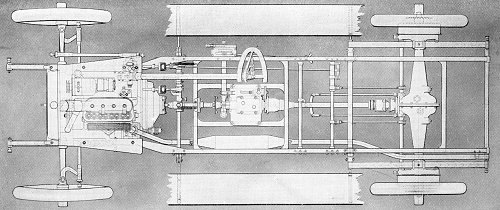

Another view of the 11.9 chassis.

|

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

| Production began in earnest in

January 1920 and soon 80 chassis were

completed each week. Unfortunately the Dudley factory

couldn’t produce enough bodies and so an order for 2,000

bodies was placed with Handley Page of Cricklewood. In

1920 around 2,000 Beans were produced. |

|

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

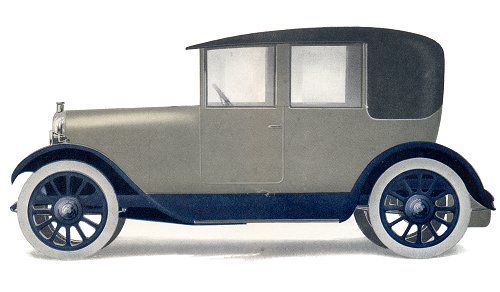

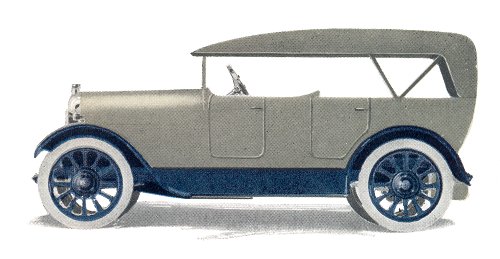

The Bean 11.9 four seater coupé

with the hood up. |

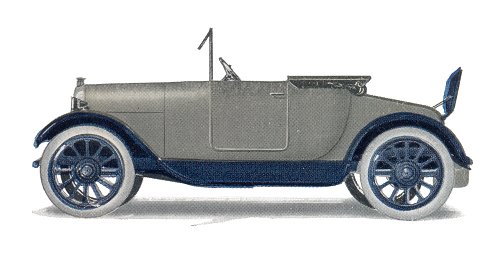

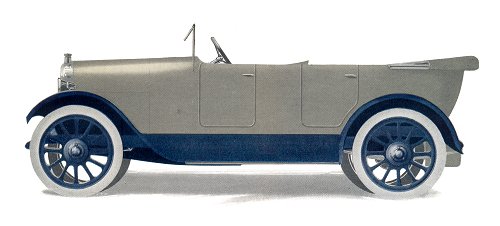

| A side view of the Bean four seater coupé. |

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

|

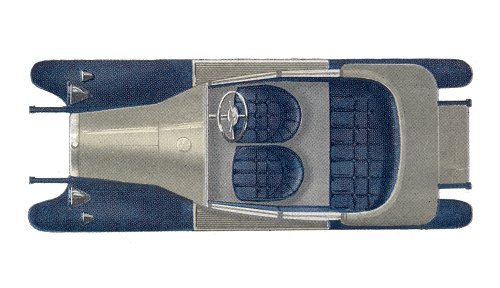

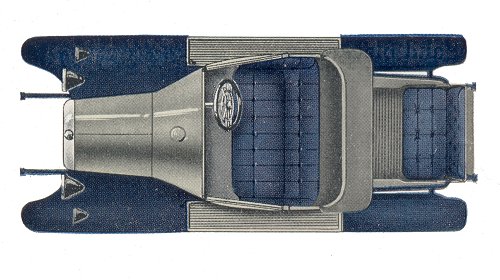

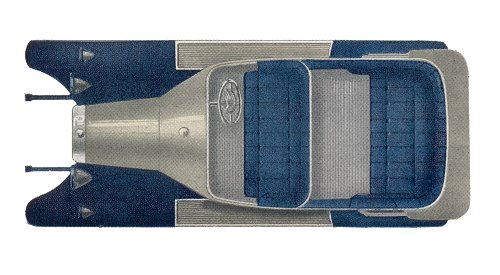

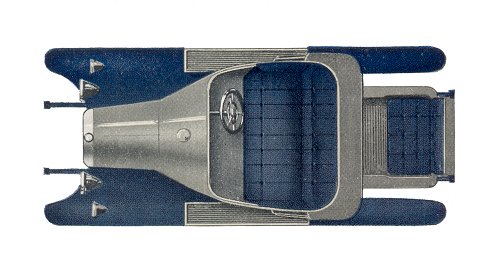

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

A plan view of the Bean four seater coupé

showing the seating arrangements. |

| The Bean 11.9 two seater coupé

with the hood up. |

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

|

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

A side view of the Bean two seater coupé

showing the dickey seat. |

| A plan view of the Bean two seater coupé

showing the seating arrangements. |

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

|

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

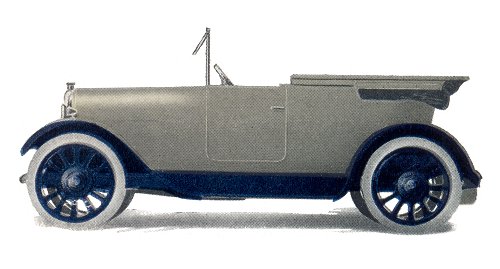

The Bean 11.9 four seater touring model with the

hood up. |

| A side view of the Bean four seater touring

model. |

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

|

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

A plan view of the Bean four seater touring

model showing the seating arrangements. |

| The Bean 11.9 two seater touring model with the

hood up, showing the dickey seat. |

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

|

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

A side view of the Bean two seater touring

model. |

| A plan view of the Bean two seater touring model

showing the seating arrangements. |

From the 1919 Bean catalogue. |

|

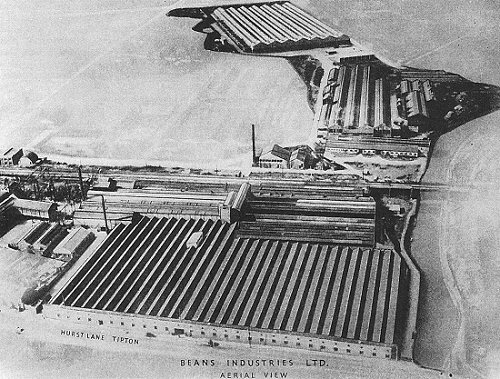

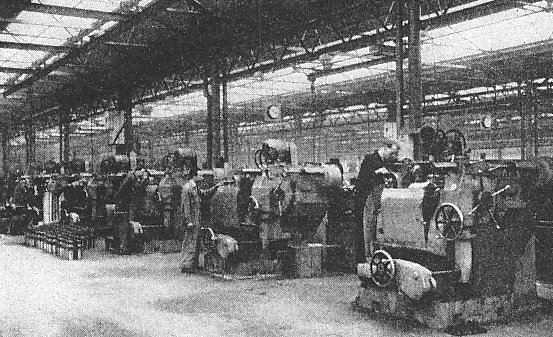

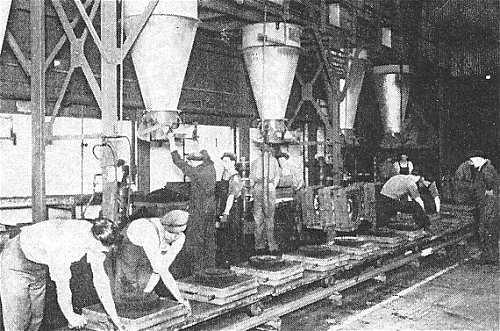

The Tipton factory covered a large

site alongside Hurst Lane and the canal. The foundry

covered 122,000 square feet, with four 360 ft. long

bays, five cupolas, overhead cranes with capacities

ranging from five tons to fifteen tons, and an output of

250 tons of castings per week.

The main factory was extremely well

organised, with electric trucks conveying materials from

one part of the factory to another. The machine shops

were organised on a 'flow system' so that materials and

components progressed in an orderly fashion to the

assembly lines. The shops were fitted with the most

up-to-date machinery including a large plane miller

capable of machining twelve sets of cylinders at a time.

There were seven multi-spindle drilling machines which

could drill seventy two holes in one operation. Three of

them were used to tap the forty four holes in the

cylinder blocks and crankcases. There were twenty gear

cutting machines, automatic machines to machine front

and rear hubs, and a machine to drill and ream big ends

and connecting rods, four at a time.

There was an array of grinding

machines in the grinding department, and seventeen

gas-fired furnaces in the heat treatment section. All

completed engines were thoroughly tested with a

dynamometer and had to develop at least twenty one

horsepower.

The assembly shop covered an area

of 450 ft. by 90 ft. and had a long constantly moving

assembly track on which the chassis frame was drilled,

and all of the components were added in sequence. The

engines were lowered into place with a pneumatic hoist

to minimise handling, and groups of fitters alongside

the track carried out the assembly work. At the end of

the track, the completed chassis ran down a slope to the

test track, where they were driven, and any necessary

adjustments made before starting their journey to

Waddams Pool Works, where the bodies were fitted.

During the

early summer of 1920 the selling prices rose dramatically,

mainly because of wage rises. The price of the 2 seater

tourer increased to £600, and the 4 seater tourer

reached £650, both models costing considerably more than

the competition. As a result the company was forced to

slash the prices in order to undercut the competition,

in readiness for the Motor Show that autumn. At the show

the 4 seater was on offer at £545.

To add to the company’s troubles,

the post war boom in the car industry had come to an end

and the following recession rapidly saw the end of the

Harper Bean conglomerate. The company owed around

£475,000 to trade suppliers and so a receiver was

appointed. Production ended at Tipton in October 1920

and in the following month Jack Bean resigned from the

company.

Rejuvenation

During November 1921 a huge

investment of capital by Sir George Bean, Barclays Bank,

The National Provincial Bank, and Hadfields enabled them

to buy a 55% controlling interest from Harper Bean and

repay the creditors. This allowed A. Harper, Sons & Bean

to manage their own affairs again, but would have

serious financial implications five years later.

Production of the Bean 11.9

restarted early in 1922. The car had an improved clutch

and was available as an open 4 seater tourer, and a 2

seater with dickey. Production slowly increased,

reaching 100 cars a week by August. |

|

Maurice Luscot Evans' Bean

11.9 tourer from 1926. |

| Another view of Maurice

Luscot Evans' Bean car. |

|

|

The 1925 Bean 11.9 tourer

that belongs to Mrs. D. Thomas. |

|

Stuart Gray's Bean

tourer from 1924. |

|

|

October 1923 saw the launch of a

new car, the much larger Bean 14, powered by a 13.9hp.

engine and fitted with a 4 speed gearbox. Several

different bodies were available ranging from a tourer, a

3 seater with dickey, a coupé, a four door saloon, to a landaulette. The car sold particularly well in

Australia, partly due to the exploits of Francis Birtles

who made the first double crossing of the continent by

car. He drove a Bean 14 from Sydney to Darwin and back.

| |

|

| Read an article

about the 14 horsepower Bean car |

|

| |

|

The Bean 12, a smaller version of

the Bean 14 was launched in May 1924. Four models were

available, ranging from a 2 seater plus dickey, a coupé,

a 4 seater tourer, to the top of the range brougham.

In November 1924 the company

launched the first Bean commercial vehicle, a 25 cwt.

chassis based on the 13.9hp. engine and gearbox. The

vehicles mainly appeared as a lorry, but vans,

ambulances, coaches and light buses were also made.

Sadly the company’s chairman Sir

George Bean died in 1924 at the age of 68. He was

replaced by Major Augustus Clerke, Hadfield’s Managing

Director, and a director of Bean since 1921. |

|

Malcolm Knowles and his

Bean 14 tourer. |

| Another view of Malcolm

Knowles' car. |

|

|

The company's offices in

Sedgley Road West. The building was sold to Tipton

Council in 1935. |

An invoice from the mid 1920s.

The Tipton factory in 1925.

|

The 1925 Bean

14 that's on display at the Black Country Living

Museum, Dudley. |

| Another view of the Black

Country Living Museum's Bean 14. |

|

|

The interior of the

Black Country Living Museum's Bean 14. |

| Unfortunately the company suffered

from an acute shortage of cash with debts totalling £1.8

million, mainly due to the restructuring in November

1921. As a result Hadfields the Sheffield steel

producer rescued the company and renamed it Bean Cars

Limited, in June 1926.

An advert from June 1926.

An advert from 10th June,

1927.

The Hadfield Era

Initially little changed after

Hadfields’ takeover. The same models continued in

production, but there were changes in management. Hugh

Kerr Thomas became a director and took over as General

Manager, and Jack Bean left Dudley in April to go on a

world tour to promote the company’s products. He

returned in March, 1927 and promptly resigned as

Managing Director to join the Board of Guy Motors.

To reduce overheads, some of the

Bean factories, including the Dudley site were sold.

From now on production would be concentrated at the

Tipton site, where a new body shop was completed in

1927.

|

|

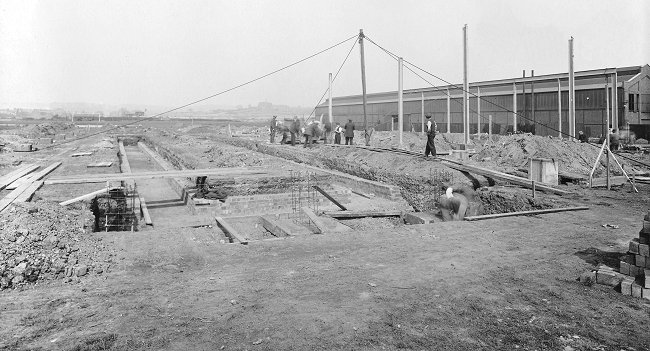

Work on the new body shop was

well underway by 13th May, 1927. |

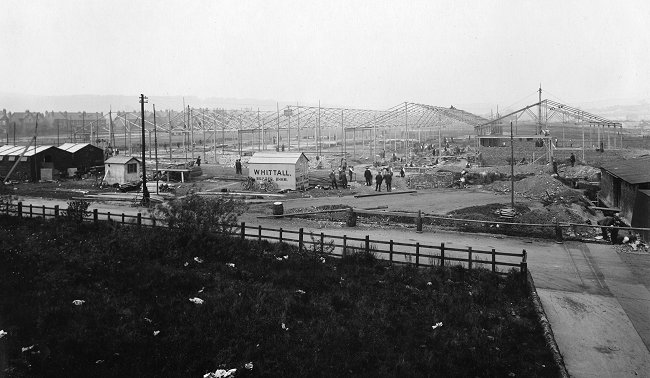

Work on the new body shop

progresses rapidly. By 26th May much of the

structural steelwork was in place. It was made by,

and installed by Wilfred Robbins Limited of Golds

Hill Ironworks, Great Bridge. |

Within a few days the

structural steelwork was complete. The remainder of

the building was built by Whittall of Birmingham.

|

|

1927 saw the introduction

of the 18/50 that was powered by a 2.7 litre, overhead

valve Meadows engine with a Meadows gearbox. They also produced a

similar car called the “Imperial Six”. Francis Birtles

attempted to drive one of the early prototypes from

England to Australia, but gave up in India after the

second failure of the car’s back axle. The car never

made it into production. Undaunted, he returned in

October to have another go, this time in his faithful

Bean 14 called “The Sundowner”. He achieved his goal by

reaching Melbourne nine months later.

Francis Birtles'

Bean 14, which is now in the collection

at the National Museum of Australia, in

Canberra. Courtesy of Trevor Hickman. |

In 1927 a number of changes were

made to the existing product range. Bean 12 production

ended, around 3,000 had been built. The Bean 14 became

the Long 14, and the Short 14 was introduced. This

consisted of a Bean 12 chassis, powered by a 14 engine.

The Long 14 had a relatively short life. It was

discontinued in 1928.

|

An advert from 1927.

|

In January 1928 the Hadfield Bean

14/40 designed by R. P. Turner went into production.

Powered by a 2,297c.c. engine, it had a top speed of

nearly 60m.p.h. Several versions were available, ranging

from a 5 seater tourer priced at £325, a saloon priced

at £495, to the Sunshine saloon with a folding roof.

March saw the introduction of the

Hadfield Bean 14/45, one of the worst car designs to

ever go into production in the UK. It had a top speed

of 65m.p.h., Dewandre servo brakes, powerful beam

headlights, and wide doors. The saloon sold for £435, and a

5 seater tourer was priced at £325. Fabric bodied

versions were also available as the Hadfield Bean 14/70.

The car went into production before the design had been

fully tested and developed. It resulted in a long

catalogue of faults which soon became apparent. Amongst

the problems were frequent back axle failures, and an

extremely heavy clutch. |

An advert from 1928.

|

Bean cars had gained a reputation

of being average, but reliable performers. The

14/45 put an end to all that. The company soon got a

bad reputation, and sales fell to around 25 cars a week.

By March 1929 the number of new cars with faults that

were returned to the factory, was higher than the number

of cars being produced. Returns also included some

faulty 30 cwt. commercials. As a result car

production ended in 1929, and efforts were made to

improve the reliability of the commercials, which continued

in production for another two years. In June

1931 the company went into voluntary liquidation and

vehicle production ended.

|

Cars

Produced |

|

Title |

Factory Model No. |

Years

in Production |

| 11.9 |

1 |

1919

to 1922 |

| 11.9 |

2 |

1923

to 1924 |

| 14 |

3 |

1923

to 1928 |

| 12 |

4 |

1924

to 1927 |

| Short

14 |

6 |

1927

to 1928 |

| 18/50 |

7 |

1927

to 1928 |

|

14/40, 14/45, 14/70 |

8 |

1928

to 1929 |

|

Beans Industries

| A new chapter started in November

1933 when Hadfields re-launched the business as Beans

Industries. The new company would produce castings for the motor

industry.

The business soon became profitable again, and

in 1936 the drop forging business at Smethwick became

Smethwick Drop Forgings Limited, later becoming part of

GKN.

In 1937 Beans Industries became a public company. |

Trademark. |

Record Breaking

In 1937 a final car was built at

the Tipton works when the company obtained the contract

to build George Eyston’s world land speed record

breaking car the ‘Thunderbolt’. The car, powered by two

Rolls Royce V12, 36.5litre engines, each delivering 2,350b.h.p.,

weighed 7 tons. One of the engines had previously

powered a Schneider Trophy winning aircraft.

There were three axles and eight wheels.

The two leading axles steered, and were of varying track.

The driven rear axle had twin tyres to spread the

weight.

At the rear was a large triangular tail fin to provide

directional stability, and on top were the engine

air intakes, and the exhaust outlets. The driver sat

ahead of the engines, behind the second pair of

front wheels. |

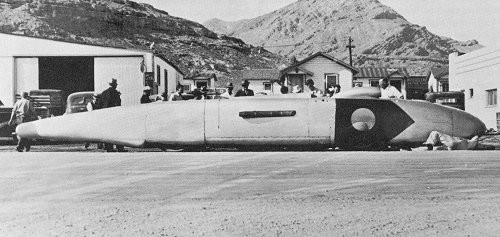

The 'Thunderbolt', as originally built.

| The air intake pipes for the superchargers were

brought to the top of the body to avoid sucking-in

the salt spray from the dry Utah lakebed, where the

record attempt was to take place. Each engine had

its own clutch, with a drive to the 3 speed gearbox.

From the gearbox the drive was taken to the

differential-less rear axle via a bevel and crown

wheel. The dimensions of the car were as follows:

length - 30ft. 5inches; height

- 46 inches; width - 7ft. 1½

inches

|

|

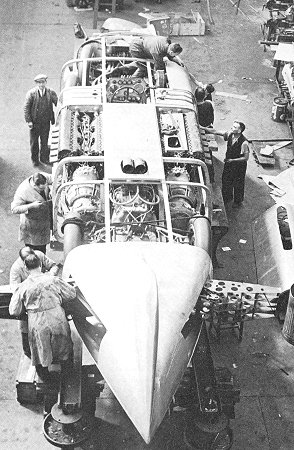

The Thunderbolt; under

construction at Tipton. |

Eyston and his team took the car to

the Bonneville Salt Flats in America for the record

attempt. The team arrived in October 1937 but

proceedings were delayed for a fortnight due to clutch

problems and bad weather. During a couple of trial runs the

car easily reached 230m.p.h.

The first attempt on 28th October

ended in failure. On the first run of the 10 mile

course the car reached 310m.p.h. but during the

return run the dog clutches that coupled the two

engines failed. Another attempt a week later ended

with same result,

the car achieved 310m.p.h. on the first run, but the

clutches again failed during the second run.

As a result new clutch parts

made to Eyston's design were hurriedly produced by

two racing engineers in Los Angeles. The parts

arrived on 17th November and two days later the car

was ready for another attempt on the record.

On the first run the car

achieved 305.59m.p.h. and reached 319.11m.p.h. on

the return run. The average speed for the kilometre

was 312m.p.h., and for the mile, 311.42m.p.h. George Eyston

had broken Sir Malcolm Campbell’s existing record by 11m.p.h.

|

|

In 1938 the car returned to the

salt flats for another attempt at the record. Several

modifications had been made to the car. The streamlining

was improved with a rounded nose, and a fully enclosed

cockpit was added with a respirator for the driver. The

first attempt on the record took place on 24th August

and Eyston and the car performed superbly reaching

347.155m.p.h. on the first run. Unfortunately things

went wrong on the equally fast second run when the time

keeping equipment operated by Art Pillsbury failed to

register the time. It seems that the sensor failed to

register the shiny car against the white salt

background. As a result a black arrow with a yellow disc

was painted on the side of the car to cure the problem.

On 27th August the car returned

for another attempt on the record. This time

everything went well, and the car achieved a new

record of 345.49m.p.h.

On 12th September Eyston's

rival John Cobb made an attempt on the record in his

Napier-Railton car, reaching 342.5m.p.h. Three days

later he took the record at 350.2m.p.h. |

|

Undaunted, Eyston prepared to

have another go at the record. After his last

success he hurriedly made some improvements to the

car. He completely covered the nose after removing

the radiator and replacing it with a tank cooling

system, and also removed the tail fin. On 16th

September he was ready for another attempt on the

record. After a wonderful performance the

Thunderbolt re-took the land speed record after

achieving 357.5m.p.h. |

The Thunderbolt in its final

form. |

|

Unfortunately the car was

eventually destroyed by fire during a tour of New

Zealand in the early 1940s. The remains of the engines

can be seen in the Museum of Transport and Technology,

Western Springs, Auckland.

Back to Tipton

During World War 2 the company

produced lorry engines, parts for army trucks, and parts

for aircraft.

|

|

An advert from 1954. |

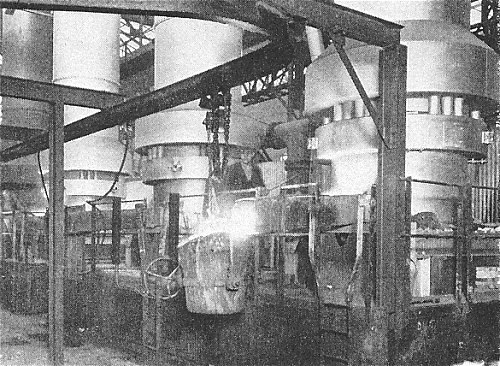

In the early 1950s the business went from

strength to strength. By this time, the foundry

alone covered an area of around 297,000 square feet,

and could produce five hundred tons of iron castings

each week. The foundry had a large number of

up-to-date machines, used to manufacture automotive

components and assemblies of all kinds. It had a

sand handling plant, moulding machines for medium

repetitive work, and a traditional floor moulding

section for jobbing work.

Production included castings of almost every kind

for numerous industries, and castings for

vehicle manufacturers including flywheels, brake

drums, manifolds, and gearboxes.

The cylinder section produced over 1,000 castings

a week, for all kinds of cylinder blocks, heads, and

crankcases. The general section produced large

numbers of high quality engineering castings from a

few pounds up to five tons in weight.

They included machine tools, press castings,

cylinders for marine oil coolers, steam jacketed

tube moulds, tractor transmission cases and axle

sleeves, diesel engine beds, columns, motor

gearboxes, oil engine parts, hydraulic cushion

cylinders, etc., etc. |

| Precise control of everything from pig iron,

sand, and all materials, through to the finished

cast metal was carefully maintained. Each ladle of

metal was individually tested to ensure that the

correct composition was used for each casting, to

guarantee high tensile strength, combined with good

machineability.

The firm gained a high reputation for the quality

of its castings, and for providing an efficient and

reliable service to customers. |

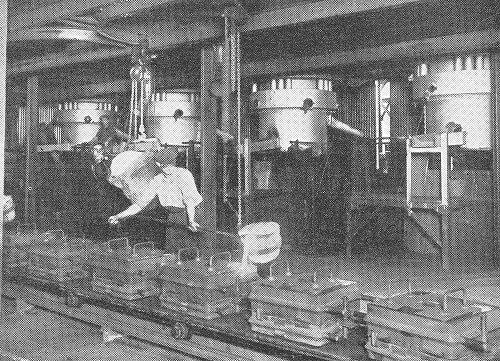

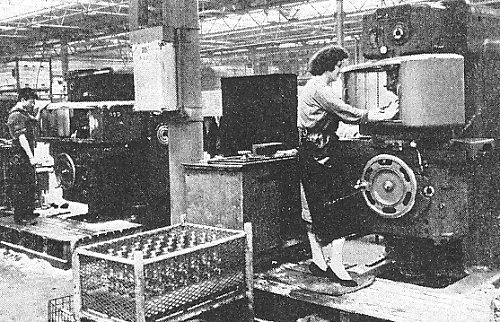

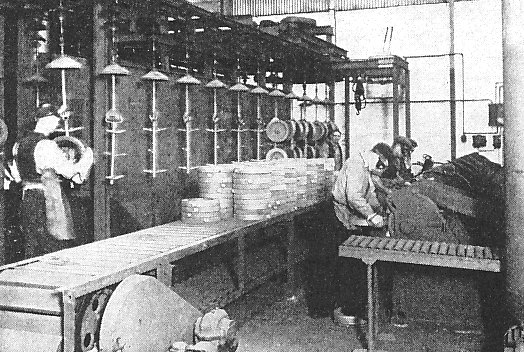

Casting in the foundry. |

|

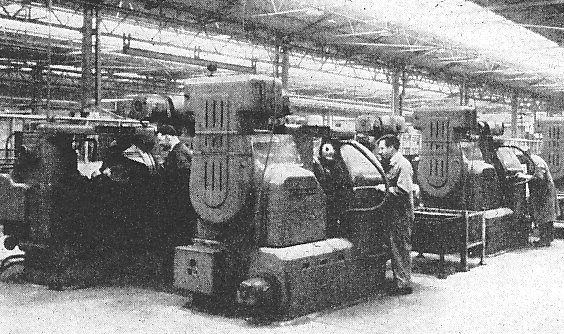

One of the gear cutting lines. |

The Engineering Division manufactured precision

engineering components and assemblies for vehicle

manufacturers, railway locomotive builders, tractor

builders, and marine industries. Products included

vehicle transmissions, axle assemblies, machined

cylinder blocks, cylinder heads, crankcases, and

gearboxes.

The up-to-date machinery and plant ensured that

work was produced to the highest standards, and to

fine tolerances.

Skilled operators were used, and their work was

closely supervised and inspected at every stage. |

| There were facilities for efficient heat

treatment, and a modern tool room which produced all

the essential jigs, tools, and equipment needed for

production. The extensive experience gained in the

factory enabled the firm to produce a vast range of

components for a large number of industries. |

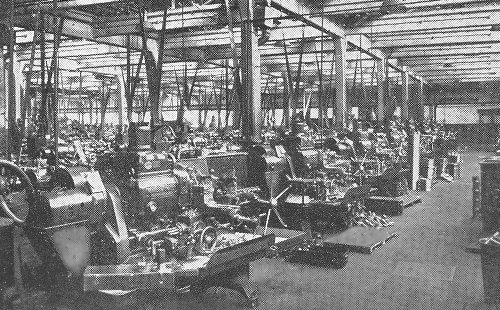

A row of capstan turret

machines. |

|

Horizontal and vertical boring

machines. |

In

1956 the company was taken over by Standard-Triumph to

produce castings for their vehicles, including cylinders

made from "Bilchrome" a special cylinder iron

developed in-house. |

| The fully mechanised foundry concentrated on the

production of a wide

range of vehicle castings, including flywheels,

brake drums, manifolds, and gearboxes, ranging in weight

from a few pounds to 60 lbs. The main products,

castings for cylinder blocks, cylinder heads, and

crankcases were produced up to a weight of 1,000

lbs., and over 1,500 such castings were produced each

week.

At this time the foundry produced around 600 tons

of castings a week. |

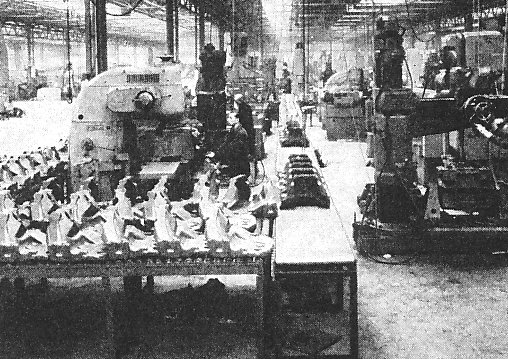

The production line for

tractor front axle supports. |

|

The production line for

tractor differential carrier plates. |

The castings were machined in the engineering

division where components and complete assemblies

were produced for vehicles, tractors, locomotives,

and boats. The division had 500,000 square feet of

floor space, and had the most modern machine tools

including capstan and turret lathes, Bullards and

automatics, vertical turning and boring machines,

centre lathes, and Fischer copying lathes. |

| There were also Plano and duplex vertical and

horizontal milling machines, multi-drillers and

tappers, gear grinders, rotary surface grinders,

gear shapers, and hobbing machines for straight

bevel gears. Spiral bevel gears could be produced

up to twenty one inches in diameter. |

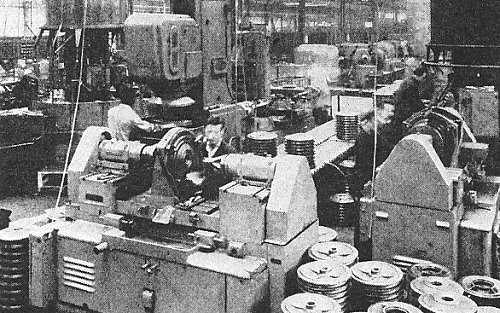

The gear shaving line. |

|

The spiral bevel gear section. |

The division's main products were machined

cylinder blocks, heads, crankcases, flywheels, fuel

pump valves, fuel accumulators, motorcycle

components, complete transmission units for

agricultural and commercial vehicles, locomotive and

marine gearboxes, textile and printing machinery,

axles, shock absorbers, test rigs, gun mounts,

turbines, heading machines, record presses, wire

drawing machines, hydraulic buffers, and

coal-cutting machinery. |

| In 1960 the company became

part of British Leyland, producing castings for their

lorries and coaches. In 1975 it became known as Beans

Engineering. |

The gear cutting section. |

|

A letterhead from 1986.

Courtesy of Ann Jackson. |

|

Mr. J. B. Davis receiving a gold watch for

25 years service with the company, in 1971. He is

standing on the left. On the 11th December,

1986, Mr. J. B. Davis received his long service

award after 40 years with the company, at a presentation at

The Prince of Wales, Tipton Road, Woodsetton,

where he was presented with the award by Mr. L.

O'Toole, General Manager.

Courtesy of Ann Jackson, Mr. Davis's

daughter. |

|

Another view of the

presentation for 25 years service. Courtesy of Ann Jackson. |

|

The foundry cupolas. |

In 1988 when the Leyland group

was privatised and broken-up by the Conservative

Government, Beans Engineering was acquired by its

management team, and after the buyout it acquired

Reliant. Things went on much as before until Reliant

failed in 1995 and took Beans into receivership. |

| The Tipton factory was purchased by

the German engineering group Eisenwerk Bruhl who made a

large investment at the works, where 40,000 tons of

cylinder blocks could be produced each year. The

business became known as Bruhl UK but suffered from

financial problems because the large investment had left

the company in debt.

For a second time the management

team purchased the business which then became Ferrotech.

|

The foundry grinding section. |

|

The foundry moulding section. |

The

factory had one of the most modern and efficient

foundries in Europe and became a large supplier of

castings to Rover. Unfortunately Rover went into

administration in 2005, and Ferrotech failed to find a

replacement customer.

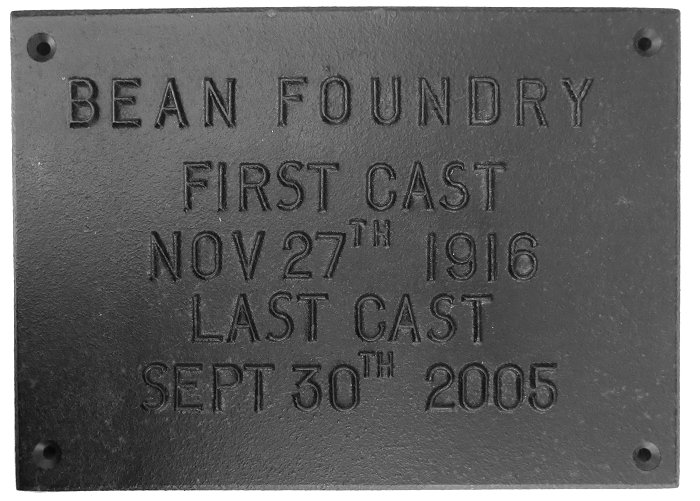

As a result the story ends in September 2005 when Ferrotech closed its doors for the last

time. |

|

A cast-iron plate, cast to

commemorate the closing of the foundry. Courtesy

of Nigel Martin. |

|

Another casting, cast

to commemorate the closing of the foundry.

Courtesy of Nigel Martin. |

|

An advert from 1957.

The remains of the old

factory, as seen from the canal in 2017. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|