|

Introduction

To the north east of Penn Common,

on the slopes of the Colton Hills, is an area of open

countryside known as The Seven Cornfields. Although it

is now associated with Pennwood Farm, and has a long

agricultural past, it was once the site of an important

local industry, brick making.

Large numbers of bricks were needed

for new housing developments, as Wolverhampton expanded

to cater for its growing population. The Black Country

changed dramatically as industrialisation began to

dominate the landscape, and people moved into the area

to find employment in the new factories. During the 19th

century the UK population almost trebled, but the

increase in the local population was far greater.

Population increases of up to 8 fold occurred in some

areas, as the proportion of people living in towns

increased from 20% to 80%.

The fine glacial clay deposits on

the southern side of Wolverhampton were ideal for brick

making, and so several brickworks were built in the

area. Most Black Country towns had at least one

brick-maker who took full advantage of the locally mined

coal and the excellent canal and road network that

covered the area. Brickkiln Street in Wolverhampton is

named after the brick kilns that once stood there, and

others could be found on the southern boundary of the

old town. |

|

The location of Penn Brickworks. |

On the eastern side of Dudley Road stood the Elm

Farm Brickworks, and Pheonix Brickworks, along with

several others around Ettingshall Park.

There were also a number of brickworks around Himley

and in Gornal Wood, and in more recent times the one at

Baggeridge.

It is possible that a brickworks once occupied part

of the site of Windsor Avenue playing fields, in Penn, because

the old meadow that once stood along the northern side

of Linton Road was called Near Brickkiln. |

|

Penn Brickworks

Penn brickworks has long

disappeared, but the site has never been redeveloped,

and today is scattered with remains from the demolished

buildings and the old spoil heaps.

No documentary information about

the works has so far been discovered, but it is marked

on old maps, and is remembered by the descendants of the

last owner, Samuel Flavell. Unfortunately the

descendants of the original owners, the Lakin family,

know nothing about the business, other than that it was

owned by the family. What follows is based on evidence

from old maps, remains from the site, and standard 19th

century brick-making techniques. Luckily the remnants of

the spoil heaps, which have now almost disappeared, gave

an insight into what was made at the works, and possibly

when. |

| Local landowners, the Lakin family, lived in Carlton

House, which stood where Sandhurst Drive is today. The

house stood on the Colton Hills, near the top of

Sandhurst Drive, just below the summit ridge. The family

is listed in the Wolverhampton Red books, as living in

Carlton House, until the 1930 edition, but is not listed

afterwards. By 1951 the house was occupied by the Gough

family, who were poulterers. They

appear to have occupied the house until its demolition

in the late 1960s when the current houses in Sandhurst

Drive were built. |

The location of the brickworks, the gravel pits,

and Carlton House. |

|

A filled-in clay hole, now only a

few inches deep. |

The last ice age glacier to cross the site,

deposited gravels at the top of the ridge, and clay on

the far eastern side.

The Lakins fully exploited their mineral rights by

opening a gravel pit at the top of the ridge, and the

brickworks on the eastern side above the clay.

Both sites were conveniently situated next to a

relatively flat dirt track which led to Goldthorn Hill,

and allowed the gravel and finished bricks to be easily

transported from the site by horse and cart. |

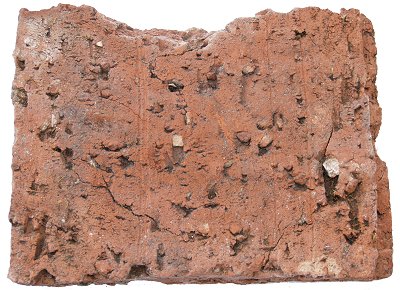

| Until a few years ago the site of the brickworks was

quite open, and much could be seen. During the last two

or three years the site has changed beyond recognition.

It is now completely overgrown, and in places is two

metres deep in weeds and saplings. Many of the bricks

lying around the site, both in the spoil heaps, and in

the base of the factory walls, have been removed, as

have many of the tiles from the floor of the kiln. It

now looks almost identical to the other overgrown fields

in the area. Parts of a smaller flooded clay pit still

survive, but have been filled-in, and are well fenced.

The main clay pit was situated at the north eastern end

of the site and is still remembered by the older members

of the local community. It was deep, with steep sides,

and like other clay pits, eventually filled with water.

It became known as “The Danger Pool”, and people often

tell the story of a horse and cart that fell into the

pool, and also a young child who drowned there. In the

mid 1930s the buildings were demolished, and in the

1970s, the pool

was filled-in with rubble from the site. All traces of

it are now gone. |

The site of Penn Brickworks. |

|

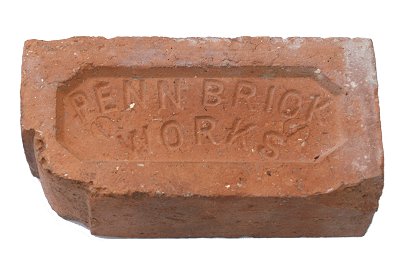

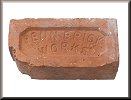

A Penn brick. |

Evidence from the

site

Until a few years ago, there was

much to see. Remains of the buildings could be seen in

the wooded area on the northern side of the site, along

with old floor tiles, and the base of the kiln.

The lower courses of the outer

factory walls were visible, as was the brick base of the

steam engine.

There were some slate roof tiles,

the top of the well, the remains of kiln fire holes, and

parts from the curved kiln roof. |

| The main building was rectangular in plan, as could

be seen from the base of the outer walls. It was built

of brick and had a slate roof. There were two thick,

heavy duty walls just inside the northern corner of the

building, and what seemed to be a filled-in pit.

This appeared to be the base of a steam engine and

boiler, with a pit for the flywheel. Locals sometimes

referred to this part of the building as the engine

house. The steam engine would have powered a pug mill

for mixing the clay, and possibly driven a brick-making

machine. It provided steam for drying the bricks, and

probably powered a winch to lift the clay from the

bottom of the deep clay hole. |

What remains of the outer walls. |

|

Some of the old bricks and tiles,

pushed up by tree roots. |

It is likely that most of the building would have

been occupied by a steam-heated drying room, which was

usually the largest part of any late 19th century

brickworks. There was also an office, possibly situated

at the northern end of the building near the entrance.

Some of the old bricks and tiles were pushed up by tree

roots, and many others were still in the old spoil

heaps, which consisted of the inevitable rejects that

occurred thanks to the vagaries of the firing process.

The remains of the spoil heaps contained a wide variety

of bricks and tiles that were made over a long period of

time. |

| The earliest examples were crude, hand-made products

that contained a small percentage of gravel, presumably

from the two nearby gravel pits, owned by the Lakin

family. The gravel helped to lessen shrinkage during the

firing process and so would have reduced the number of

rejects.

There were many well-made standard bricks, facing

bricks, bricks with scroll work or a motif, and also

some high quality examples that look like terracotta.

The more recent bricks were machine made, indicating

that a degree of automation was later introduced.

Some of the bricks were of a lighter colour, and

blistered, suggesting that crushed lime had been added.

Many of the tiles scattered around the site are of a

heavy industrial type. They are unusual in that they

slot together and so would ensure an even surface and

share a heavy load. |

Another view of the bricks and

tiles. |

|

The well. |

A good water supply was essential. Water would have

been added to soften the freshly dug clay to give it the

right consistency for moulding. The water came from a

well, the top of which could be seen on the north

eastern side of the main building. The works had one

kiln, about thirty feet in diameter, which could have

had a capacity of up to 20,000 bricks, depending upon

the height of the kiln and the stacking density. Much of

the tiled base remained until recently. Sections of it

were pushed-up by the small trees that grow in the area.

|

| The circular kiln, with a chimney on one side, can

be seen on old ordnance survey maps. It appears to be a

downdraught kiln which would have been fired from eight

or so fire holes. One of the spoil heaps contained

parts of the curved arches that formed the top of the

fire holes, and another contained some of the tiles that

formed the kiln roof.

The bricks for the kiln must have been made on the

site. The base was built using the company’s heavy duty

interlocking floor tiles, which were extremely strong

and hard wearing. |

An impression of how the kiln

might have looked. |

|

Part of the curved top of one of

the kiln's fire holes. |

The Brickworks in

Operation

In the early days the clay would

probably have been dug out by hand, in lumps, placed in

a soak pit, and left overnight to soften.

Roughly three cubic yards of clay

produced about 1,000 bricks. It could then be mixed with

water to form a suitable consistency for moulding.

There would have been at least one moulding table

where bricks were moulded by hand, using four-sided

wooden moulds with no top or bottom. |

| The wooden mould was placed over a rectangular piece

of wood on the table, to form the frog, and the clay

would be firmly pushed in. Finally the excess clay was

cut from the top to form the completed brick, which

would be removed from the mould and left to dry. Moulds

were often lined with a dusting of sand to prevent the

clay sticking. The moulding tables would have been

replaced by moulding machines, which must have produced

the later, higher quality bricks. Mechanisation had several advantages over

traditional methods. The pressure applied to the clay in

the mould was much greater, leading to a denser and more

uniform brick, which gave more consistent results,

leading to fewer rejects. The machines would also have

increased the number of bricks made. |

The site of the kiln, showing

floor tiles and bricks that have

been pushed to the surface by tree roots. The kiln base

is made of the company's interlocking floor tiles,

several of which can be seen above. |

|

Trees growing through the base of

the kiln. |

The moulded bricks would be stacked

on racks to dry, where each brick could loose as much as

half a pint of water.

Before the steam engine was

installed, this would be a lengthy process because the

bricks would take a considerable time to dry, possibly

never fully drying in the winter months.

If this was the case, the

brick-making would have been seasonal. |

|

Another view of the site of the

kiln. |

The dried bricks would have been carefully stacked

in the kiln, and coal in the fire hole grates would be

lit to produce the hot gases that were directed upwards

from baffles to the underside of the domed roof. The

gases would then flow downwards through the stacked

bricks and out through the chimney. The floor would be

perforated for this purpose. Once fired, the kiln

would be fed with coal through the fire holes, and

stoked every half an hour, both day and night. The kiln

had to be constantly attended for around two days until

it had reached a temperature of possibly 1,000 degrees

centigrade. The firing then continued for a further day

to maintain the temperature, while the bricks baked.

Three or four days later the kiln would have cooled

down sufficiently for the bricks to be removed. The

whole process took just over a week. Great care was

needed to reduce the number of rejects. Some were to be

expected, but a whole kiln-full would be disastrous. Two

ruined kiln-fulls in a row could lead to bankruptcy. |

| Emptying the kiln must have been one of the most

unpleasant tasks. It would have been emptied as soon as

possible after the firing process, to maintain

production. This meant that the kiln would still be

quite warm, and the bricks would not have fully cooled.

Although all of the bricks in the kiln were made from

the same clay, their final colour would depend upon

their position in the kiln. The ones in the centre would

reach a higher temperature and so could be darker and

much harder than the others. |

One of the floor tiles from the

kiln. |

|

The underside of a floor tile

showing the clay-gravel mixture. |

On the 1901 map there appears to be a ramp leading

from the main building, down into the large clay pit, so

the clay would have been hauled into the building on

some kind of trolley, before being placed in the pug

mill, which was probably near to the steam engine at the

northern end of the building.

The map also shows two small outbuildings on the

site. These could have been stables, coal bunkers, or

coverings for the straw that would have been used for

packing. |

|

A number of people would have been

employed on the site, mostly doing dirty and unpleasant

work for little pay. Some would be digging clay, or

operating the pug mill. Others would be operating the

moulding machines or stacking the moulded bricks in the

drying room.

The kiln would have a number of

attendants who stacked the bricks, controlled the fires,

and then emptied the kiln at the end of each firing.

There would have been a person in charge of the boiler,

and someone to look after the horses and carts that were

used for transportation. |

The top view of one of the unusual

floor tiles. |

Many of the tiles scattered around

the site are of a heavy industrial

type like the two above. They are unusual in that they

slot together and so would ensure an even surface and

share a heavy load. |

If a quantity of bricks was

ordered, the customer’s name could be stamped on the top

of each brick. "Beacon View" cottage, owned by Len

Collins, was built from Penn bricks, and the Collins

name is on each brick. The cottage was built around 1890

by Len's grandfather, who was a milkman.

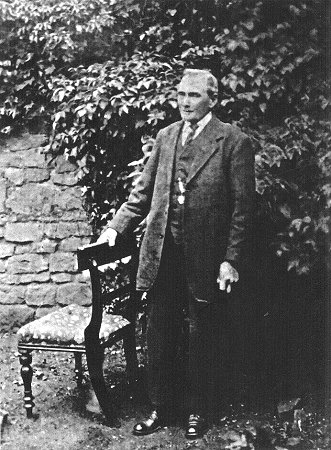

Around 1900, Samuel Flavell purchased the brickworks,

which he ran for a number of years. He was born around

1836, and at the age of 24 married Rachel at Sedgley

Parish Church. He was the underground Manager at Corbyns

Hall Colliery, Dudley, where he gained an

award for his handling of a pit fall. In the 1901 census

he is listed as a brick manufacturer. His son Arthur,

aged 20 is listed as a clerk in the office at the

brickworks. |

|

Samuel lived at 10 New Street,

Gornalwood, and was proud of one of the large orders,

which was for bricks for the building of Queen Victoria

School in Bilston Street, Sedgley.

The transportation of the bricks

became increasingly more expensive, and so Samuel

decided call it a day. It appears that he tried to sell

the business, but without success.

By this time Samuel lived at 12a

Gospel End Street, Sedgley, not far from the old

brickworks. Samuel and his son Arthur, and other members

of the Flavell family would go for walks across Penn

Common to see the works, and no doubt reminisce about

‘the good old days’. Samuel died in November 1927.

After closure, the buildings

remained empty for some time, and were demolished in the

mid 1930s.

|

Samuel Flavell. Courtesy of

Cheryl Nicholls. |

|

What remained of The Danger Pool

in later years. Courtesy of Lawson Cartwright. |

I would like to thank

Cheryl Nicholls for information about the Flavell family

and their involvement at the brickworks, and

|

|

Return to

the

Penn Menu |

|