|

Banks, Offices and Commercial Premises

There

has always been buildings devoted to large-scale commerce such

as the Bank of England and Custom House, but they were mainly in

London. Smaller businesses often occupied rooms in a house.

However in the early 19th century commercial buildings began to

emerge with a distinct and separate existence. Insurance and

banking went through a rapid process of transformation, partly

as a result of the financial legislation in the 1840s that

helped to shape the security of investment. Much bank and

commercial architecture began to reflect this increased

confidence.

The

other types of commercial premises that began to emerge were the

so called “Office Chambers”. By the end of the 19th century the

process of separating offices from living quarters was virtually

complete. Due to the need to maximize land use there was a

demand for greater height and as artificial light was not yet

feasible, larger windows. To give an impression of stability

many were built in the Classical style, but this caused

problems, as the style was not always compatible with tall

many-windowed facades. Wolverhampton has many fine “Chambers”;

perhaps the most notable is the Quadrant Building in Princess

Square built in the 1890s. Although the ground floor has been

altered to accommodate shops, the upper part of the building

still retains its fine façade. Another fine set of offices is

Gresham Chambers, opposite the Art Gallery.

Queen

Square has some excellent buildings and part of the attraction

is the three fine banks that face it. Of these the finest must

be that housing Barclays Bank, built in 1876. The original

design was by T.H. Fleeming, but it was added to on subsequent

occasions. It is a masterpiece of Gothic architecture containing

a bewildering variety of features. It is of three storeys with

slightly projecting gables with arches either side. There are

turrets, and facing Lichfield Street, to the left of the door

leading to the chambers, a loggia.

|

Lloyds TSB bank in Queen Square. The

Italianate facade of the building works very well. The extension to

the building, on the site of the old Queen's Ballroom has been very

sensitively carried out. |

Although

Barclays is a masterpiece, Lloyds is probably a more architecturally

correct building and a great deal more restrained in the Italianate

style. Although the façade is as Pevsner says,

“sparing in motifs”, there are some interesting relief panels

showing industrial scenes placed somewhat incongruously on the

front. The left hand panel shows a scene in a coalmine complete with

cage, winding gear and coal truck. The middle panel shows an

agricultural scene with heavy carts full of produce. The right hand

scene shows heavy industry with drop forgers at work; in the

background there is a rolling mill in operation. The panels are a

deliberate attempt to show scenes of plenty and the fruits of

labour; they also indicate, whether intentionally or not, the twin

sources of much of the town’s wealth. As the Art gallery and Bank

share the same architect and were built at the same time, the panels

are by Boulton of Cheltenham, as are those on the former building.

The National Westminster

Bank on the north side of the square is in marked contrast to

the other two, caused partly by its white stone. Corinthian

pilasters separate pedimented windows. |

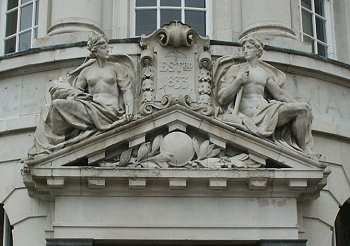

| It is of

three storeys with a balustrade disguising the roof. Over the

doorway are two figures representing Industry (with a hammer) and

Agriculture (with a cornucopia).

A commercial premises

occupies one of the most massive pieces of Victorian

architecture in Wolverhampton, that of the Royal London Mutual

Insurance, built at the end of the period, 1900 to 1902. |

The exquisite carved panels on Lloyds Bank,

showing left to right, coal mining, agriculture and industry. |

| We have said

before that the Victorians built in a wide variety of architectural

styles. The Baroque style of this building was a late development of

the 19th century, a reaction against the “Free Style” which had

developed combining Classical with Gothic motifs, well illustrated

by the library. Of particular interest on this building is the use

of glazed terracotta over the entrance. There is a mass of carving

on the building carried out by the firm of Carter and Co. of Pool. |

The fruits of agriculture and industry are personified by the two

figures above the door of the NatWest Bank. |

In an

early chapter, it was pointed out that Wolverhampton was very

much a market town and many of the commercial buildings erected

had an agricultural purpose; sadly these have now entirely gone.

The

Exchange public house is a reminder that near to this site stood

the Exchange building, erected between 1850 and 1853 to a design

by G.T. Robinson. The building was originally intended as a corn

exchange for farmers and millers. Shares raised the money for

its building, £15,000.

|

|

The

main room was 120 feet by 50 feet and had a gallery, a permanent

platform and an orchestra pit capable of containing over one

hundred players. Despite this the acoustics were apparently

dreadful. The Exchange was also used for ironmasters and other

public meetings. There were newsrooms attached to the building,

which were well supplied with national and provincial papers.

From

the start the building proved to be unsatisfactory and there was

an acrimonious public debate as to where blame should lie. The

Secretary of the Exchange Company tried to blame the architect

as the building was poorly lit, badly ventilated and the sound

was poor. Good lighting was essential to the corn merchants who

needed to see the quality of the corn.

One

feature of the original building was a large cupola which had to

be removed almost immediately as it began to subside into the

building. The architect who advised removal was Ewan Christian

who was called in for advice. It was said at the time that it

was the only building ever built with the foundations at the

top. The Exchange did not have a very long life, being

demolished in 1898.

|

| A fairly

recently demolished commercial building was the retail market. This

had been opened in March 1853 at a cost of £30,000 and built to a

design by Lloyd of Bristol. Photographs of the building show an

impressive Italianate classical façade with entrances in North

Street and Cheapside. The Market, which came into the hands of the

Corporation yielded between £3,000 and £4,000 per annum in 1896. |

The

Wholesale market. “A pretty building” |

| It was

reported in the same year that this was gradually increasing. Its

main interesting features were the hollow, cast-iron columns, which

not only acted as a support, but carried away rainwater also.

We have confined

ourselves rather strictly to those buildings which qualify as

Victorian, but one exception is the Wholesale market, which was

built in 1903-4. “A pretty building”, according to

Pevsner, it was demolished in the 1970s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Schools

and Colleges |

|

Return to the

contents |

|

Proceed to

Entertainment & Leisure |

|