|

Entertainment and Leisure

Like

all major towns, Wolverhampton was well supplied with places of

entertainment. Unfortunately only one of these, The Grand

Theatre, remains from the town’s 19th century theatres. In

Bilston Street was the Star Theatre and Concert Hall, which was

built in the Elizabethan style and entirely rebuilt in 1883. In

Cleveland Road was the Theatre Royal erected in 1844. The

original theatre was at the top of the Swan Hotel yard in Queen

Square (or High Green as it was then) and was built about 1779.

Mrs. Siddons performed there on many occasions and legend has it

that the great tragedian John Kemble made his acting debut

there.

Music

Halls, few of which have survived, were thought of as subversive

places of entertainment as well as places of beer and gin. What

is not often realised is that they were often quite political

where one was as likely to hear a parodied version of a popular

Jingoistic song as the real thing.

Any

discussion of Wolverhampton buildings used for entertainment

must begin with the Grand Theatre. It has been described as

”the finest miniature opera house in Europe” and few would

quibble with that description. A few years ago when it appeared

that this delightful building was in danger of never opening

again, many people felt a sense of almost personal loss. Like

many local people, the writer’s earliest theatrical experiences

were all at the Grand.

|

|

The Grand Theatre, Lichfield Street. |

The decision

to build the theatre in Lichfield Street had been made as early as

February 1894 by the then mayor C.T. Mander, who was the driving

force behind the scheme, and about six others. The site was

important for the theatre; it was near the town centre, on a main

thoroughfare and next door to the hotel, which had been enlarged to

make it a first class establishment. The proprietors of the Victoria

Hotel were quite pleased that there was going to be a new theatre on

their doorstep and shareholders were encouraged to buy an interest

in the new place of entertainment. |

|

The

actual building of the theatre was entrusted to the

Wolverhampton firm of William Gough, who took only six months to

complete the work after the laying of the foundation stone by

Mrs. C.T. Mander. The theatre is a product of the “naughty

nineties”, being built between 1893 and 1894 to a design by the

architect C.J. Phipps, one of the first architects to specialise

in theatre design. It was designed to seat 2, 500 people and

cost £12,000. Phipps was a prolific theatre designer and his

other commissions include the Savoy Theatre and Nottingham’s

Theatre Royal. The Grand Theatre also incorporated four shops,

two on either side of the entrance which is 123 feet across.

The

opening night of the theatre was on December 10th 1894 with a

performance by the D’Oyle Carte Opera Company performing Gilbert

and Sullivan’s Utopia Unlimited.

|

|

The

latter years of the 19th century were a golden age of theatre

building. It is strange that the times of the greatest theatre

building do not always coincide with periods of great dramatic

writing. Theatre architecture is very much linked with the

social climate of the day because it is a social art. Play

writing in the 19th century before the arrival of Chekhov, Ibsen

and Shaw was at low ebb. However playwrights such as these often

had conflicting aims, which were in conflict with those of

theatre architects. The latter were concerned with creating an

environment to accommodate all levels of society; the great

dramatists were intent on reform and social examination as well

as entertainment.

The

façade of the Grand has a continental look with a five bay upper

loggia of arcading. A cast iron porte-cochere extends over the

pavement. Inside there are deeply recessed balconies fronted by

ornate stucco work.

|

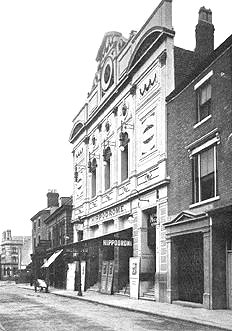

The Hippodrome, Bilston Street. |

| Like all

theatres, the Grand reflected social divisions; different bars,

entrances and toilets for the patrons of different parts of the

house.

It was

whilst performing at the Grand Theatre in February 1905 that Sir

Henry Irving was attacked by the serious illness which

terminated fatally at Bradford later in the year. The young

Charlie Chaplin was recorded as a call boy in 1902 and he also

starred at the Grand in one of his first acting debuts as Dr

Watson’s page boy (!) in Sherlock Homes.

Many

Victorian theatres and music halls have either been destroyed or

insensitively “adapted”. Wolverhampton is fortunate in retaining

the Grand.

|

|

The Elephant and Castle that was in Stafford

Street.

|

There are in

Wolverhampton some fine examples of pub architecture, although many

have gone and those remaining do not contain their original

fittings. Although some people get very romantic about good pub

buildings, it should be remembered that they had one function and

one function only and that was to sell beer and make as much money

as possible. Many underhand methods were employed to make people

drink more, including adding salt to the brew. (Now pubs just sell a

wide range of salty snacks). |

| In the 19th

century the brewery interest was very powerful and not for nothing

was it known as the “Beerage”. There are in Wolverhampton some fine

examples of pub architecture, although many have gone and those

remaining do not contain their original fittings. |

| One of the

best examples of pub architecture was the Elephant and Castle just

off the Ring Road. The façade was of exuberant green glazed brick.

For a sign it had a splendid model of its name on the corner. The

tiling was perfect and extremely well-preserved with the name of the

pub written on the two sides facing the two roads. Above the doorway

was written Wines and Spirits in ceramics of the very highest order

of quality. |

What remained of the beautiful and much

loved Elephant and Castle after its hasty demolition. |

| There was a

projecting black and white gable above the model sign and below that

a decorative border. The Elephant and Castle achieved the brewery’s

main aim which was to create a landmark building. The Elephant was

not only one of the most famous buildings in Wolverhampton but also

one of the best loved.

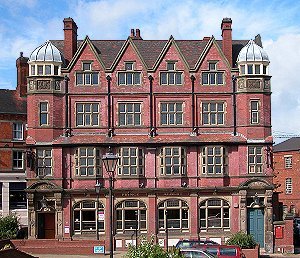

In the City centre, the

recently refurbished Posada still retains many of its original

features, including the glazed tiles below the window and

inside, but most of all the beautiful Art Nouveau lettering of

its name above the window and down the side entrance. The Prince

Albert and Sir Tatton Sykes are both good examples of imposing

late Victorian pubs. The former is one of our favourite façades

having as it does an excellent symmetry. At the top are two

cupolas on either side of four steep gables. Each of the storeys

uses a different design for its four windows. The first storey

windows are bowed and those at the ground floor have arches. The

two doorways either side of the building complete the symmetry. |

|

The Prince Albert pub.

|

Recently the Town hall Tavern has been refurbished and

renovated. One outcome of this was the removal of plaster work

above the first floor which revealed a row of exquisite sky-blue

tiles, some patterned, some with fleurs-de-lis, others having

letters making up the legend “Wine and Spirit Merchant”.

Entwined numbers in stone above the door give the date 1874.

Although the inside of the pub has been ruthlessly altered, the

façade of the Old Still retains its ability to impress,

guarding as it does the entrance to King Street, a street that

can probably still boast of being one of Wolverhampton’s most

elegant streets.

|

|

The

Exchange in Cheapside was recently vandalised when the old

fixtures and fittings were torn out to be replaced by imitation

old fixtures and fittings. Progress of a sort one supposes.1

Unfortunately, many of Wolverhampton's Victorian pubs

disappeared during the construction of the Ring Road. I would

pick out five, the first being the Blue Ball at the end of

Pipers Row.

Notes:

| 1. |

It is

strange how some breweries (not of course Wolverhampton’s

premier brewery) deliberately trade on their old fashioned

traditional image and at the same time have engaged in

architectural vandalism and philistinism on a breathtaking

scale. How

people who harp on their “heritage” can so ruthlessly

destroy and disguise it is a mystery. When one local pub was

undergoing a particularly ruthless transformation into a

Giggle Palace or Fun Factory, I wrote to the brewery

concerned and asked if the beautiful plaster mouldings,

brass work, heavy oak doors and etched windows had at least

been passed on to a dealer in architectural antiques. The

reply expressed blank amazement that anyone should have

asked such a ridiculous and naive question. |

|

|

|

|

Return to

Banks and Offices |

Return to the

contents |

Proceed to

Architects

and Craftsmen |

|