Industry, Water and Rail

The

industrial revolution gave to England an enormous variety of

industrial architecture, structures and engineering works, much

of it only being now appreciated. Often a care and attention to

architectural detail was lavished on these buildings that went

beyond their functional need. Mills built in the 17th century

can, at first glance, be taken for country houses, as mill

owners sought respectability for the their profession by

disguising its nature. In a town such as Wolverhampton, where

industry was so diverse, industrial premises reflect this,

ranging from the small workshops to large factories. Not all

industrial premises were purpose built; many of the smaller ones

especially were adapted from other buildings. One form of

building that lent itself to these in more recent times was

redundant Nonconformist chapels. We had thought that there were

no chapels converted to industrial use in Wolverhampton. However

at the bottom of Temple Street is a small premise that, despite

having a new façade, looks by its side windows as if it may once

have been religious building. The large numbers who converted to

Nonconformism, and the chapels built to serve them, were not

sustainable when numbers began to decline. The problem of

redundant chapels is at present acute in parts of Wales.

|

|

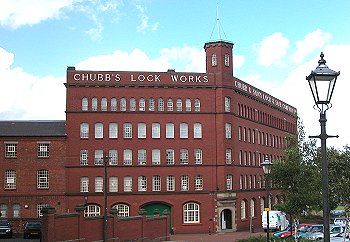

The old Chubb lock works. |

Both

Wolverhampton and parts of Willenhall are synonymous with lock

making and one of the most famous names is Chubb. Within

Wolverhampton town centre, there are remarkably few industrial

premises, but one is particularly striking and that is the former

Chubb Lock factory in Railway Street that dates from 1899. It is a

dramatic building of five storeys, occupying a prominent corner

position. It is of unusual shape, being triangular with a stair well

at the apex. It has recently been sensitively adapted for use as a

cinema and arts centre. |

| The 18th

century saw rapid developments in the field of transport. Turnpike

roads, first introduced in the 17th century, spread rapidly and

gained in popularity until they linked at least all the major towns

with reasonably prepared roads. Wolverhampton Turnpike Trust was set

up to develop through Tettenhall to Shifnal. Tettenhall was also the

scene of a major rock cutting when Thomas Telford took through a

section of the London-Holyhead Road. By 1763 no less than seven

turnpike roads met at Wolverhampton. |

|

It was,

though, the coming of the canals that provided industry and

commerce with a means of transporting heavy or bulky goods. The

canal network that developed was of prime importance to the

development of the midlands in general and the Black Country in

particular, for Birmingham and the Black Country were at the

heart of the English canal system. In the area between

Birmingham, Wolverhampton and the Teme valley there is a network

of canals at three levels approached by a long flight of locks. |

Canalside cottages and lock number one.

|

| There are

tunnels, signposts, tollhouses and lock keepers cottages. This

system was considerably extended in the 19th century.

Unfortunately nothing remains of Wolverhampton’s turnpike

system, although tollhouses exist on the Willenhall Road. The

canal though has provided us with some interesting arrangements

of Victorian buildings, though not as many as we would wish.

The

Staffordshire and Worcester Canal that runs through the

outskirts of Wolverhampton and partly financed by the town’s

businessmen, was the work of the great canal engineer James

Brindley. The Act of Parliament authorising the canal was passed

in 1776 and Brindley was able to complete the forty-six mile

route in six years. The canal begins at Great Haywood on the

Trent and Mersey Canal and follows the valleys of the Penk,

Smestow and Stour to join the Severn at Stourbridge. The

Staffordshire and Worcester canal is joined just out of town at

Aldersley by Telford’s Birmingham Canal and it is this which

runs across the bottom of Broad Street. Later the canal was

extended to Nantwich under the name of the Birmingham Liverpool

Junction.

|

|

Another view of the canal cottages.

|

Until the

1970s a graceful cast iron bridge took the Wednesfield Road over

the canal, this has now been removed to the Black Country Living

Museum where it can still be appreciated. Near to the modern

bridge is an arrangement of wharves that after having served as

industrial premises have now been converted to use as a

nightclub, currently defunct. In Broad Street Basin there is an

interesting group of canal cottages. |

| It is often

asserted that the coming of the railways brought about the sudden

demise of canals and whilst it is true that there was some

consternation amongst canal proprietors the change was not so

dramatic as is often thought, especially in the midlands where the

canal network was both complex and efficient and could often not be

improved upon by the railways. The Cannock extension was built as

late as 1853, a decade after “railway mania”. |

|

When the

railways came to Wolverhampton, providing great stimulus to its

industries, it was at the centre of controversy between two

rival companies.

The

Grand Junction Railway, which connected Birmingham with the

Liverpool and Manchester line, was opened in 1837. As lines only

approached the centre of town as closely as was necessary to

make a connection, the Grand Junction came no nearer than Heath

Town, then Wednesfield Heath.

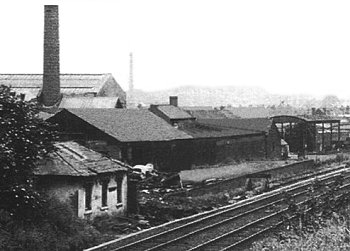

|

Wednesfield Heath Railway Station, long

after closure.

|

|

The

name Station Road is a reminder of where it once was. An

additional problem for Wolverhampton was the fact that it was on

hill.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

The Chapel |

|

Return to the

contents |

|

Proceed to

Schools and Colleges |

|