|

Churches and Religious Buildings. 3 - The Chapel

The Victorian age is

considered, rightly or wrongly, as a great age of Faith.

Religion, especially that of Nonconformity (that is the Chapel

rather than the church) lay at the heart of industrial middle

class life. Most middle class Nonconformists belonged to three

great persuasions; Congregationalists, Baptists and Wesleyan.

Despite their often minute doctrinal or organisational

differences, most Nonconformists had the same outlook: work,

faith and duty. The strong strain of Puritanism that existed in

religious life from the 17th century found its modern expression

in the Congregationalists or Independents. It was not always a

chapel for the working class. “Our, said one Congregationalist

minister, is not a church of the poor”. The Congregationalists

were especially strong in the great towns and the works of

Samuel Smiles were almost as much a pillar of their belief as

the Bible. They prided themselves on their independence, indeed

each congregation was independent of all others; each chose its

own pastor and each ran its own affairs. Those Pastors in charge

of a congregation would be well paid, much more so than a

clergyman of the Established Church.

The

history of Non-conformism in this country is a complex one, for

minute doctrinal differences between groups led to an

increasingly fragmented following. Many of the different

persuasions attracted a different class of people. Whilst

persuasions like the Wesleyans may have been the preserve of the

middle class, others catered for the needs of the less well off.

The diversity of Nonconformism is shown by the number of names

given to their chapels1. We have Primitive

Methodists (the “Prims”), Particular Baptists amongst others.

The congregation of each was not only determined by social class

but by place of work. Just what divided these disparate groups

are to most of us a mystery.

In

White’s Directory of 1851 it states, “Dissenters are as

numerous in Wolverhampton as in most other towns of similar

population, having no fewer than twelve places of worship”.

In

England there is a special connection between the Nonconformists

and the new towns or rather industrially expanding towns where

they knew that they had a special strength, even though they

could not claim the allegiance of the large masses. In

Wolverhampton, Nonconformist attendance made up more than 50% of

churchgoing. Nonconformists themselves were not a unified body,

either in terms of social composition or economic strength, as

the wide range of chapels show. Towards the end of the century

they were more important than their numbers suggest as they were

often influential in local affairs. The Unitarians in particular

played a great part in civic life providing mayors and officials

and encouraging interest in reform. Nonconformists were Liberal

to a man but of course not all Liberals were Nonconformist.

The

study of Nonconformist architecture has been much overlooked in

this country. Most of the books on church architecture tend to

concentrate almost exclusively on that of the Church of England,

with occasional forays into buildings used for Roman Catholic

worship. The chapels and meeting places of Quakers, Baptists and

others have been relatively neglected.

After

about 1850, Nonconformists began to employ specialist architects

as well as more respected local ones.

|

|

Darlington Street Methodist Church. |

Many also

tried to give uniformity and a more recognisable form to chapel

architecture. F.J. Jobson, the Methodist architect, published a book

called “Chapel and School Architecture”, where he maintained that

chapels are not meant to be like concert halls. He speaks of the

“House of God” and “scriptural holiness”2.

Although he regards the Gothic style with some praise, he reiterates

the traditions of Nonconformity, that of hearing the word and seeing

the minister. The central aisle, such a feature of Anglican churches

is ruled out. |

|

Often

the main interest in Nonconformist chapels is the interior.

Whereas parish churches have been subject to numerous

alterations over the years in response to the whims of this or

that movement, or the fad of the incumbent, chapels and meeting

places tend to have retained their original furnishings intact.

For Dissenters, the most important focal point of the building

was the pulpit; hence there was no reason for a choir and apse.

Seating arrangements centred on the need for as good a view as

possible of the preacher. Seats were angled to avoid interrupted

vision or even placed in a horseshoe fashion. In the galleries

the seats are usually raised on tiers. Sometimes the whole floor

was raised so that no one’s line of vision was obstructed.

The

pulpit too, as the focal point, became more and more elaborate.

First they acquired testers; then they were set on elaborate

rostra surrounded by balustrades. When women began to preach in

the chapels, a presumably easily excited congregation erected

panels called modesty boards to prevent them seeing a glimpse of

ankle. One important feature of Victorian Nonconformist chapels,

especially those that date from the latter half of the century,

is the provision of subsidiary facilities. Rooms were provided

for the preacher and possibly the sexton and also reading and

education rooms often with a church hall too.

The

wealth, or otherwise, of Nonconformist groups, led to the

building of a wide spectrum of chapels from the humble side

street, to the magnificent town centre buildings. All of them

had this much in common though; simplicity of interior

decoration, where the study of the word of God took precedence

over meditation and imagery.

|

| The Methodist

Chapel in Darlington Street, built to replace a chapel of 1825, is a

large, powerful building that almost makes a mockery of the

designation chapel.

Until recently it was in

danger of demolition; as the Queen Street Congregational Church

had already suffered the same fate, its rescue is to be doubly

welcome.

The chapel was

constructed late in the reign of Queen Victoria; in fact it only

just qualifies for inclusion in this book as it was not finished

until 1901, the year of the Queen’s death. In 1899 the previous

chapel on the site had needed re-pewing and it was found that

considerable renovation was needed. |

Darlington Street Methodist Church today. |

| It was

therefore decided to demolish the old chapel and erect a new one,

more in keeping with the influence wielded by the Methodist body and

“better fitted for the aggressive work of evangelism which the

20th century was going to inaugurate”. Whilst building was in

progress the Agricultural Hall was used for services.

What is

most striking about the building (and what was almost the cause

of its downfall) is the huge spherical copper dome that is such

a dominant feature of the Darlington Street skyline. There are

also two façade turrets. The best place to see the chapel is not

from the front but from the bottom of Skinner Street. From here

the great hemispherical dome can be seen to best advantage. It

rests on a drum that has four pedimented windows with three

narrow windows in between. During the research for this book we

had many pleasant surprises but nothing prepared us for our

first visit to this chapel for the inside is not merely powerful

but also movingly beautiful; not only grand but bordering on

the theatrical. From the inside as the outside, the most notable

feature is the dome, which from the inside has much delicacy

partly due to the Art Nouveau glass.3 The

triforium is, unusually inlaid with mosaics. However it is the

tall double Corinthian columns that are so striking. The bottom

column holds up the horseshoe gallery. The large pulpit with

seating, occupies as expected the central place in the chapel

with choir stalls behind. It is small wonder that after the

opening ceremony the services proved a great attraction to the

town, so much so that many seat holders found it impossible to

occupy their seats, even half an hour before services began.

As

noted before there are often numerous rooms for meetings,

education, living rooms etc. in Methodist chapels and here too

they are much in evidence but they were built at a later date.

Inside the administrative rooms are three blacked windows that

show the extent of the original building before later additions.

|

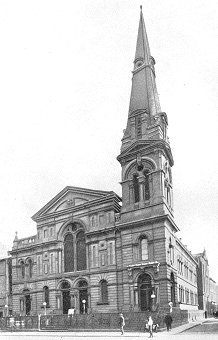

The Congregational Church, Queen Street. |

Of

equal size and impressive character (it seated 1,250 people) was

the Congregational Church in Queen Street that was demolished in

1970. The architect was Bidlake who lived in Waterloo Road next

to the subscription library. The impressive nature of this now

sadly demolished building should not really surprise us, for as

stated in the introduction, the Congregationalists were some of

the wealthiest of the Nonconformist sects and in Wolverhampton

they numbered the Mander family amongst their adherents. There

was a further Congregational chapel next to the Roman Catholic

church of S.S. Mary and John in Snow hill, a building described

as “A structure of imposing appearance, in the decorated

Early English style”. This was built by John Barker the iron

founder of Chillington. There are, unfortunately, no Quaker

meeting houses left in Wolverhampton. The Quakers, or to give

them their correct name the Society of Friends, had a meeting

house in Broad Street. Although this has now gone, the burial

ground, which is a dedicated public open space, still exists on

the corner of Westbury Street and Broad Street.

|

Notes:

| 1. |

The nickname

given to one Nonconformist group in Willenhall was the High Flyers

due to their belief that they were nearer to God.

|

| 2. |

Interestingly, Nonconformist places of worship have much in common

with the great Franciscan churches of Italy where too the word was

of primary importance. So empty and cavernous are they that they are

known as “preaching barns”. |

| 3. |

Another small

Art Nouveau feature of this chapel are the elegant door handles. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Non Conformism |

|

Return to the

contents |

|

Proceed to

Industry, Water and Rail |

|